The Rhino Issue Manager Final Report 2012 now available for Downlaod from the PMG site:

PDF - 22 March 2013

RIM Report 2012/2013

Re: Rhino Issue Manager Final Report 2012

1.2 Rhino presence

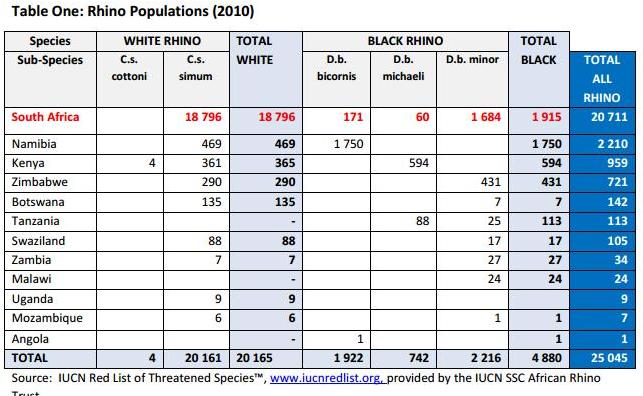

Over 90 per cent of Africa’s white rhino occur in South Africa. Approximately 1 400 white rhino occur in Namibia, Botswana, Swaziland, Zimbabwe and Mozambique and small numbers are present in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania (Mkhize, 2012). Today, game ranches in South Africa cover an area over three times as large as all the national and provincial protected State areas (Milliken & Shaw, 2012). Best estimates suggest that the national herd consists of approximately 15 000 white rhino owned by the State and approximately 5 000 in the hands of private owners on some 395 private ranches and 36 state protected areas (Mkhize, 2012) on over 5 million hectares (Eustace, 2012).

Currently, Kenya, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe conserve approximately 98% of Africa’s black and white rhinos.

The Ecological Carrying Capacity (ECC) is the capability of a given area to optimally hold a specific number of a species. South Africa is fast approaching the limit of the ranges available to white and black rhino on state owned land and is currently at over 80 per cent of carrying capacity (Emslie, 2012). This means that in order to continue to grow the species, new ranges or the expansion of existing ranges in other states will be required soon.

Established rhino populations should be maintained at 75 per cent of Ecological Carrying Capacity (ECC) to maintain actively growing populations, and provide surplus animals (5 % and 8 % of population) for other populations & growth areas.

1.3 Key and Important Rhino Populations

While there are many rhino populations not all are critical to the sustainable conservation of the species. Key One populations are considered to be of continental importance and critical for rhino populations ecological function. Striving to establish larger populations serve rhino conservation more than a myriad of smaller, fragmented populations. In 2010, South Africa held six key and 12 important black rhino populations, and 19 key and 41 important white

rhino populations, resulting in a total of 78 key and important rhino populations in the area.

This is followed by Kenya, with a total of 15, Namibia with a total of 12, and Zimbabwe with a total of eight (Emslie, 2012). Any strategy for conservation of the species should take cognisance of the priority of the key and important populations in terms of resource allocation. For certain populations this will require partnership with other range states.

1.4 Kruger National Park

The largest population of white rhino in the world exists in the Kruger National Park (KNP). In 2010, estimates indicated the presence of 10,621 white rhino in the park (Ferreira, Botha & Emmett, 2012). Since the late 1990’s, white rhino have been translocated from the KNP for biodiversity and conservation reasons and sold to generate conservation revenue. By 2010, 1 402 had been removed, largely to other conservation areas, with no adverse effects on the population and numbers continued to increase in the park. However, the number of poached white rhino is now exceeding the number of white rhino that the SANParks white rhino management model – outlined below- requires (4.4% of the standing population at any given time). At these increasing rates of poaching the number of surplus rhinos available in the next few years will reduce, and the overall population is expected to decline in 2016 (Ferreira, Botha & Emmett, 2012).

These predictions depend on white rhino population data being precise and there are some concerns in this regard as a result of potential for bias and differences in survey methodologies deployed over time. However, surveying wildlife, especially species such as black rhino, is notoriously difficult. The current KNP survey results have been published in the peer reviewed literature as confirmation of scientific accuracy & reliability and are considered to be as accurate as scientifically possible (Ferreira et al 2011, Ferreira et al 2012).

If there is significant downward variation in the current trend which assumes a continued upward linear growth in poaching, then matters could be significantly worse than they are at present. Additionally, poachers tend to target adults resulting in changed population structure which could cause rapid population collapse once population thresholds are reached (Ueno, Kaji & Saito, 2012). Poaching has already impacted on the provision of live white rhino to other areas to extend the species range as well as on the funds earned which contribute towards conservation (Ferreira, Botha and Emmett, 2012).

Surveying rhino every two years offers the best option for detecting a 2 per cent change in population estimates, currently however this budget is not provided for by SANParks Surveys need to do more than just count rhino as information is needed on age, sex, fecundity, survival and landscape use to ensure optimal conservation of the species and provide alternative population information that can corroborate population estimates. Internationally accepted best practice in terms of population survey requires helicopter block count and distance sampling approaches as two reliable and precise methods (Emslie, 2012).

The KNP is also home to over 627 black rhino at last count in 2008 with an annual population growth rate of approximately 6.75 per cent (Ferreira, Greaver & Knight, 2011). At least eight black rhino have been poached in the KNP since 2008, but the exact number, and therefore the impact on this critically endangered animal, is not known as there have been no counts of this population since October 2008. The limited reports of poaching of black rhinos would however suggest the population is growing satisfactorily.

Over 90 per cent of Africa’s white rhino occur in South Africa. Approximately 1 400 white rhino occur in Namibia, Botswana, Swaziland, Zimbabwe and Mozambique and small numbers are present in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania (Mkhize, 2012). Today, game ranches in South Africa cover an area over three times as large as all the national and provincial protected State areas (Milliken & Shaw, 2012). Best estimates suggest that the national herd consists of approximately 15 000 white rhino owned by the State and approximately 5 000 in the hands of private owners on some 395 private ranches and 36 state protected areas (Mkhize, 2012) on over 5 million hectares (Eustace, 2012).

Currently, Kenya, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe conserve approximately 98% of Africa’s black and white rhinos.

The Ecological Carrying Capacity (ECC) is the capability of a given area to optimally hold a specific number of a species. South Africa is fast approaching the limit of the ranges available to white and black rhino on state owned land and is currently at over 80 per cent of carrying capacity (Emslie, 2012). This means that in order to continue to grow the species, new ranges or the expansion of existing ranges in other states will be required soon.

Established rhino populations should be maintained at 75 per cent of Ecological Carrying Capacity (ECC) to maintain actively growing populations, and provide surplus animals (5 % and 8 % of population) for other populations & growth areas.

1.3 Key and Important Rhino Populations

While there are many rhino populations not all are critical to the sustainable conservation of the species. Key One populations are considered to be of continental importance and critical for rhino populations ecological function. Striving to establish larger populations serve rhino conservation more than a myriad of smaller, fragmented populations. In 2010, South Africa held six key and 12 important black rhino populations, and 19 key and 41 important white

rhino populations, resulting in a total of 78 key and important rhino populations in the area.

This is followed by Kenya, with a total of 15, Namibia with a total of 12, and Zimbabwe with a total of eight (Emslie, 2012). Any strategy for conservation of the species should take cognisance of the priority of the key and important populations in terms of resource allocation. For certain populations this will require partnership with other range states.

1.4 Kruger National Park

The largest population of white rhino in the world exists in the Kruger National Park (KNP). In 2010, estimates indicated the presence of 10,621 white rhino in the park (Ferreira, Botha & Emmett, 2012). Since the late 1990’s, white rhino have been translocated from the KNP for biodiversity and conservation reasons and sold to generate conservation revenue. By 2010, 1 402 had been removed, largely to other conservation areas, with no adverse effects on the population and numbers continued to increase in the park. However, the number of poached white rhino is now exceeding the number of white rhino that the SANParks white rhino management model – outlined below- requires (4.4% of the standing population at any given time). At these increasing rates of poaching the number of surplus rhinos available in the next few years will reduce, and the overall population is expected to decline in 2016 (Ferreira, Botha & Emmett, 2012).

These predictions depend on white rhino population data being precise and there are some concerns in this regard as a result of potential for bias and differences in survey methodologies deployed over time. However, surveying wildlife, especially species such as black rhino, is notoriously difficult. The current KNP survey results have been published in the peer reviewed literature as confirmation of scientific accuracy & reliability and are considered to be as accurate as scientifically possible (Ferreira et al 2011, Ferreira et al 2012).

If there is significant downward variation in the current trend which assumes a continued upward linear growth in poaching, then matters could be significantly worse than they are at present. Additionally, poachers tend to target adults resulting in changed population structure which could cause rapid population collapse once population thresholds are reached (Ueno, Kaji & Saito, 2012). Poaching has already impacted on the provision of live white rhino to other areas to extend the species range as well as on the funds earned which contribute towards conservation (Ferreira, Botha and Emmett, 2012).

Surveying rhino every two years offers the best option for detecting a 2 per cent change in population estimates, currently however this budget is not provided for by SANParks Surveys need to do more than just count rhino as information is needed on age, sex, fecundity, survival and landscape use to ensure optimal conservation of the species and provide alternative population information that can corroborate population estimates. Internationally accepted best practice in terms of population survey requires helicopter block count and distance sampling approaches as two reliable and precise methods (Emslie, 2012).

The KNP is also home to over 627 black rhino at last count in 2008 with an annual population growth rate of approximately 6.75 per cent (Ferreira, Greaver & Knight, 2011). At least eight black rhino have been poached in the KNP since 2008, but the exact number, and therefore the impact on this critically endangered animal, is not known as there have been no counts of this population since October 2008. The limited reports of poaching of black rhinos would however suggest the population is growing satisfactorily.

Re: Rhino Issue Manager Final Report 2012

2.2 Conservation of White Rhino

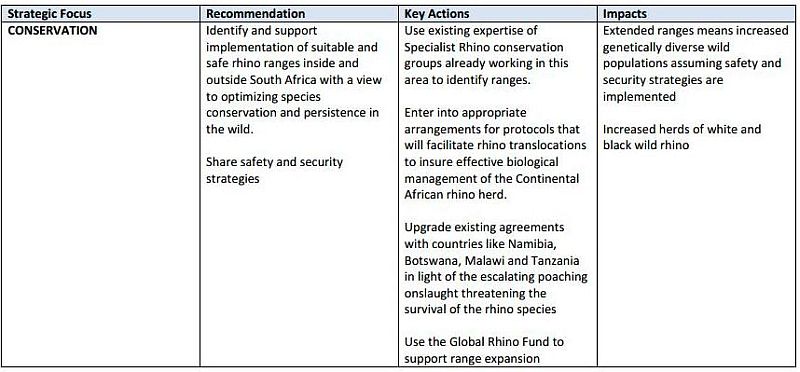

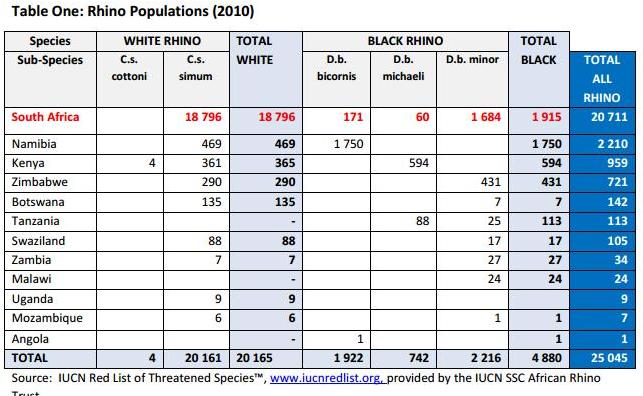

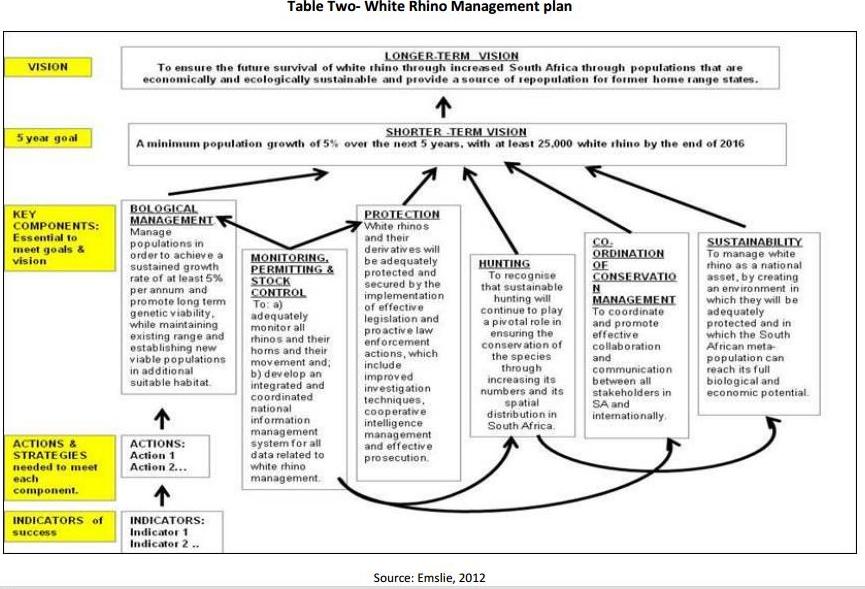

The proposed management plan for the sustainable conservation of the white rhino is in draft stage and yet to be confirmed, but it addresses the key issues for conservation as shown in the table below. Key elements are the maintenance of existing ranges, the promotion of long term genetic viability, and the establishment of new viable populations. The use of an integrated national (and potentially regional) monitoring system will be a prerequisite for effective conservation, as will adequate protection measures, (refer section two of this report).

2.3 Conservation of Black Rhino

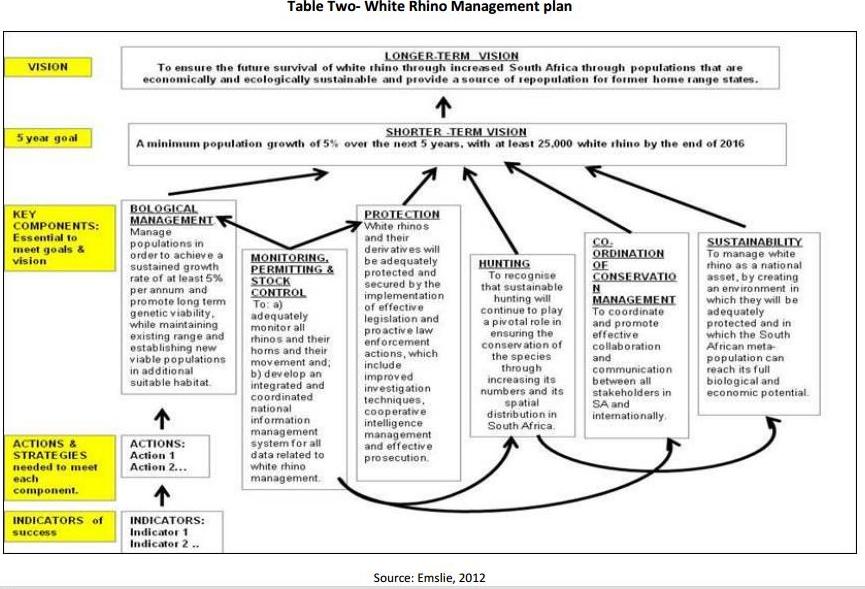

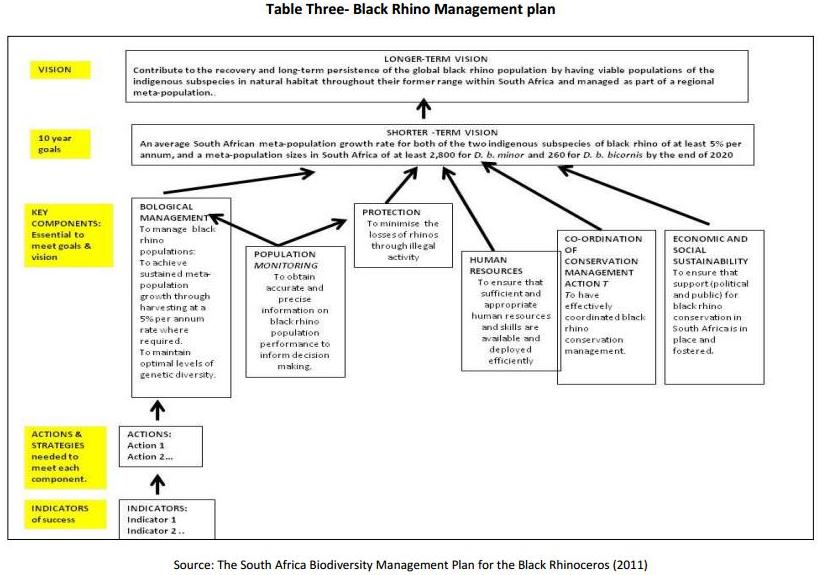

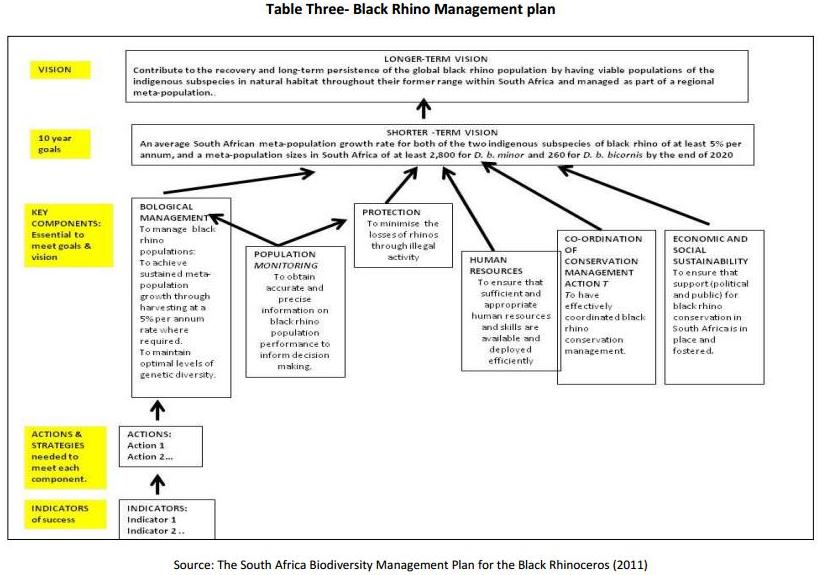

The Biodiversity Management Plan for the Black Rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) in South Africa for 2011-to 2020 awaits final approval and gazetting by the Minister in terms of the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act, 2004 (Act No. 10 of 2004). The plan was developed by South African members of the SADC Rhino Management Group15 and a key principle of the plan is to maintain a 5 per cent growth rate (historical growth rate 4.9 per cent average) resulting in a longer term overall population goal of 3 500 black rhino in South Africa. The dynamics and requirements for targeted population growth are different for the three sub-species and consequently different strategies for management are needed. South Africa has supplied founder rhinos to a number of Southern African states with a view to assisting in the re-establishment of rhino ranges and populations there. By the end of 2020, South Africa wants to have a meta-population size of at least 2,800 for D. b. minor and 260 for D. b. bicornis.

Key elements of the plan require targeting five per cent net growth in population per annum and the maintenance of maximum genetic diversity. These can be achieved through the harvesting of five per cent per annum as necessary and from populations close to their zero growth capacity (ecological carrying capacity), the establishment of new populations (du Toit, 2006), the maintenance of sub-species and range separation and the active promotion of genetic diversity. As noted above for white rhino, the use of an integrated national (and potentially regional) monitoring system will be a pre-requisite for effective

conservation, as will adequate protection measures (refer section two of this report).

The proposed management plan for the sustainable conservation of the white rhino is in draft stage and yet to be confirmed, but it addresses the key issues for conservation as shown in the table below. Key elements are the maintenance of existing ranges, the promotion of long term genetic viability, and the establishment of new viable populations. The use of an integrated national (and potentially regional) monitoring system will be a prerequisite for effective conservation, as will adequate protection measures, (refer section two of this report).

2.3 Conservation of Black Rhino

The Biodiversity Management Plan for the Black Rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) in South Africa for 2011-to 2020 awaits final approval and gazetting by the Minister in terms of the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act, 2004 (Act No. 10 of 2004). The plan was developed by South African members of the SADC Rhino Management Group15 and a key principle of the plan is to maintain a 5 per cent growth rate (historical growth rate 4.9 per cent average) resulting in a longer term overall population goal of 3 500 black rhino in South Africa. The dynamics and requirements for targeted population growth are different for the three sub-species and consequently different strategies for management are needed. South Africa has supplied founder rhinos to a number of Southern African states with a view to assisting in the re-establishment of rhino ranges and populations there. By the end of 2020, South Africa wants to have a meta-population size of at least 2,800 for D. b. minor and 260 for D. b. bicornis.

Key elements of the plan require targeting five per cent net growth in population per annum and the maintenance of maximum genetic diversity. These can be achieved through the harvesting of five per cent per annum as necessary and from populations close to their zero growth capacity (ecological carrying capacity), the establishment of new populations (du Toit, 2006), the maintenance of sub-species and range separation and the active promotion of genetic diversity. As noted above for white rhino, the use of an integrated national (and potentially regional) monitoring system will be a pre-requisite for effective

conservation, as will adequate protection measures (refer section two of this report).

Re: Rhino Issue Manager Final Report 2012

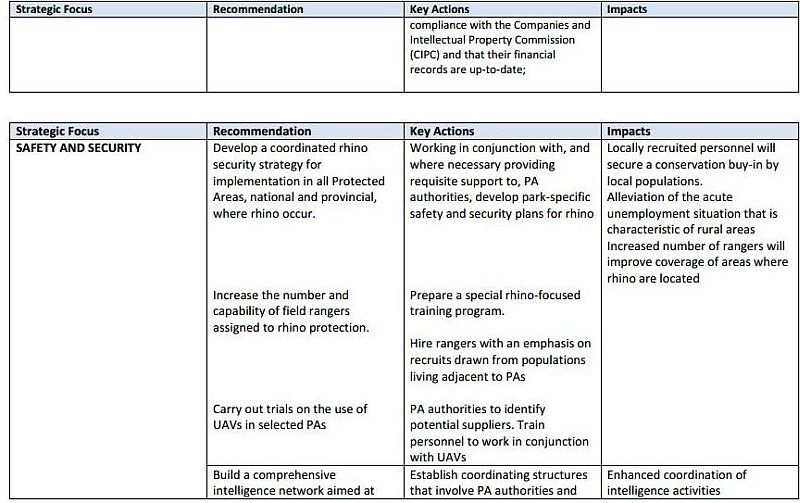

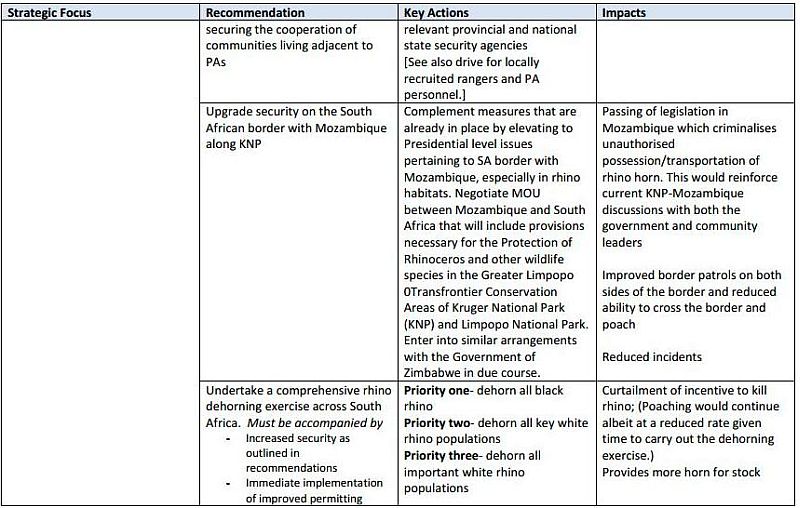

5. Safety and Security Options

5.1 Current Interventions

There is a national strategy for the safety and security of Rhino in place in South Africa which outlines the requirements for rhino protection. NATJOINTS, a South African National coordinating security body, has initiated Operation Rhino and is working to reduce the incidence of successful poaching of rhino in South Africa. Priority committees working on rhino protection have been established in the provinces, and coordinators appointed, under the instruction of NATJOINTS. Dedicated investigation teams have been set up in each province and dedicated prosecutors have been appointed. Information is reported to the central Priority Crime Knowledge Management Centre and the enforcement of environmental legislation pertaining to the rhino has been integrated into the Rural Safety Management Plan. Tracker dogs and handlers are being deployed as well as visible air patrols with increased reaction capability (Mapanye & Chipu, 2012).

SARS Tax and Customs Enforcement Investigations (TCEI) division is implementing a number of projects to ensure that rhino products are not illegally exported from South Africa and is required in terms of South Africa’s international agreements to work closely with the International Consortium for Controlled Deliveries in Wildlife Crime (ICCWC). In particular, pseudo-hunting was a major focus of investigation which has largely been addressed via new regulations. Rhino horn is additionally used for purposes of money laundering and racketeering (HAWKS, 2012).

Operation Worthy was conducted by all Interpol countries with the aim to curb rhino horn smuggling. In South Africa a combined effort from The Hawks, Interpol, National Wildlife Crime Reaction Unit, Department of Environmental Affairs, NPA, NATJOINTS and SARS was conducted. Inspections were done at taxidermists, freight agencies, airports, borders, game farms and road blocks were held at key areas and searches were conducted (HAWKS, 2012).

This resulted in the gathering of critical information and led to a number of arrests and convictions (SAPS, 2012).

Security checks are now run on all operational personnel working with rhino and security partnerships have been initiated inter alia with the veterinary profession, private rhino owners, farmers, civil aviation participants, and NGOs. The development of a shared rhino safety and security strategy is underway with the Defence Force Chiefs of neighbouring countries. Work at the wider international level is ongoing with Interpol and the NWCRI (Mapanye & Chipu, 2012). The National Wildlife Crime Reaction Unit was established and a number of provincial and local initiatives are underway in State owned areas.

Various legislation is being brought to bear to support protection efforts, to wit; the National Biodiversity Environmental Act 10/2004; the Provincial Biodiversity Environmental Acts and Ordinances; the Civil Aviation Act; the Protected Areas Act ( Act no 57 of 2003); the Firearms and Ammunition Act; all fraud and corruption related legislation and regulation; the Drug and Drug Trafficking Act; POCA and MISS. Amendments to the norms and standards for the marking of rhinoceros horn and hunting of white rhinoceros for trophy hunting purposes were published in the government gazette in April 2012 and have since been implemented. The amendments have strengthened provisions relating to marking, the supervision of hunts, the transport of the horn subsequent to the hunt, reporting and monitoring, verification of hunters, and the taking of samples for DNA profiling, and have largely reduced the threats from pseudo-hunting.

While it is clear that rhino poaching has increased, so too has the focus and activities of the South African security forces in attempts to protect the rhino. Even so, poaching levels are inexorably rising to the detriment of the species and it can only be speculated what the levels of poached rhino might have been if additional measures had not been deployed. However, more resources are needed and agreements and strategies with neighbouring countries will be essential.

5.2 Intelligence

South Africa’s focus up to now has largely been on reactive strategies, where there have been extensive attempts to focus on escalating rhino poaching. However, it will be significantly more constructive if poachers can be halted before they get anywhere near rhinos. This will only come about through an increased focus on improved intelligence collection, its analysis and the resultant implementation of strategically focused activities. Moreover, a focus on prevention rather than ex post facto apprehension will allow the state and private sector to direct limited resources into areas that can have the most impact.

The analysis of intelligence should be undertaken by skilled intelligence data analysts, with information being fed back to the source institutions as part of the shared approach to information. This kind of effective coordination is a vital element of South African antipoaching strategy going forward. Intelligence feeding into this national database would include that collected from poached animals, information on syndicates and rhino horn markets. The development of useful preventative intelligence will require greater cooperation internationally. The current problems with the leaky Mozambique border and poor legal deterrents in Mozambique are providing the poaching syndicates the opportunities to operate freely and without fear.

5.3 Dehorning

The horn of a rhino grows approximately 5 cm annually and can be harvested safely as long as the procedure is undertaken properly (Emslie, 2012; Ferreira, 2012; Knight 2012). Microchipping and DNA sampling can be implemented at the time of de-horning. The horn is made of keratin, the same substance which forms human hair and nails.

A rhino uses its horns for territory defense, self-defense, dominance assertion through sparring, cows defending calves, mating and foraging. Black rhino use the anterior horn to pull high branches down to feed on. Rhino horns sometimes break in the wild but do grow back. Dehorning is unlikely to have negative long-term effects but it will be important toensure that all male rhino are dehorned at the same time, as a dehorned rhino will be at a considerable disadvantage in fighting (Ferreira, 2012).

Dehorning offers some defense against poaching but exposes the animal to some risk as it has to be chemically immobilized, and must be repeated on a regular basis as the horn grows. Humane dehorning, which ensures that the germinal layer is not damaged, leaves the base section intact for further growth. This base could weigh as much as a kilogram and at current prices still be attractive to poachers, thus still exposing the animal to a poaching threat. Poachers also kill dehorned rhinos to ensure they do not track the animal again, although notching of the feet (Lindsay & Taylor, 2011), which indicates in the spoor that the rhino being tracked is dehorned, can be a useful mechanism to deter this. When poachers operate at night, they cannot see if the rhino has a horn or not and may simply shoot.

The numbers of rhino to be dehorned in South Africa poses a logistical and budgetary challenge especially for the larger wide spread populations such as in the KNP or in iMfolozi Park. Each rhino has to be chemically immobilized and then dehorned and in some regions this will require helicopter darting due to the terrain. The darting, dehorning, micro-chipping and DNA sampling process takes between 30 minutes to one hour and costs approximately R8000/rhino after which blood and horn samples are sent to the national database for registration. Once the rhino has been dehorned, this procedure will need to be repeated every two to three years. Mortality from chemical capture is low at around one per cent.

To dehorn 10,000 rhino at a rate of eight rhino per day, will take approximately 1 000 days, and cost in the region of R84 million in 2012 ZAR (RIM calculations, 2012). The outcome of dehorning is a reduction in perceived value as well as rhino horn which, given that trade is illegal currently, is stockpiled. If kept in a few secure locations, protection for the stockpiles can be undertaken cost effectively.

Dehorning has been used as a strategy in Namibia and extensively in Zimbabwe where complete dehorning is preferred for small populations and strategic dehorning in larger populations. In South Africa, dehorning takes place in the private sector reserves and in Mpumalanga, but has not yet been used in SANParks or any other provincial reserve except for specific management purposes. In Namibia, post dehorning, not a single dehorned rhino was poached and in Mozambique, no dehorned rhinos have been killed. In Zimbabwe, dehorning coupled with translocation is believed to have significantly reduced poaching (Lindsay and Taylor, 2011) and in the Zimbabwean Lowveld Conservancies dehorned rhino have a 29.1 percent higher chance of survival than horned rhino (du Toit, 2011). Dehorning interventions work best in conjunction with other protective safety and security measures. Where dehorning has taken place without adequate security in place however, results have not been good. In Zimbabwe, in spite of complete dehorning in certain areas extensive poaching has continued and in some areas, entire populations have been wiped out (Lindsay & Taylor, 2011)

5.1 Current Interventions

There is a national strategy for the safety and security of Rhino in place in South Africa which outlines the requirements for rhino protection. NATJOINTS, a South African National coordinating security body, has initiated Operation Rhino and is working to reduce the incidence of successful poaching of rhino in South Africa. Priority committees working on rhino protection have been established in the provinces, and coordinators appointed, under the instruction of NATJOINTS. Dedicated investigation teams have been set up in each province and dedicated prosecutors have been appointed. Information is reported to the central Priority Crime Knowledge Management Centre and the enforcement of environmental legislation pertaining to the rhino has been integrated into the Rural Safety Management Plan. Tracker dogs and handlers are being deployed as well as visible air patrols with increased reaction capability (Mapanye & Chipu, 2012).

SARS Tax and Customs Enforcement Investigations (TCEI) division is implementing a number of projects to ensure that rhino products are not illegally exported from South Africa and is required in terms of South Africa’s international agreements to work closely with the International Consortium for Controlled Deliveries in Wildlife Crime (ICCWC). In particular, pseudo-hunting was a major focus of investigation which has largely been addressed via new regulations. Rhino horn is additionally used for purposes of money laundering and racketeering (HAWKS, 2012).

Operation Worthy was conducted by all Interpol countries with the aim to curb rhino horn smuggling. In South Africa a combined effort from The Hawks, Interpol, National Wildlife Crime Reaction Unit, Department of Environmental Affairs, NPA, NATJOINTS and SARS was conducted. Inspections were done at taxidermists, freight agencies, airports, borders, game farms and road blocks were held at key areas and searches were conducted (HAWKS, 2012).

This resulted in the gathering of critical information and led to a number of arrests and convictions (SAPS, 2012).

Security checks are now run on all operational personnel working with rhino and security partnerships have been initiated inter alia with the veterinary profession, private rhino owners, farmers, civil aviation participants, and NGOs. The development of a shared rhino safety and security strategy is underway with the Defence Force Chiefs of neighbouring countries. Work at the wider international level is ongoing with Interpol and the NWCRI (Mapanye & Chipu, 2012). The National Wildlife Crime Reaction Unit was established and a number of provincial and local initiatives are underway in State owned areas.

Various legislation is being brought to bear to support protection efforts, to wit; the National Biodiversity Environmental Act 10/2004; the Provincial Biodiversity Environmental Acts and Ordinances; the Civil Aviation Act; the Protected Areas Act ( Act no 57 of 2003); the Firearms and Ammunition Act; all fraud and corruption related legislation and regulation; the Drug and Drug Trafficking Act; POCA and MISS. Amendments to the norms and standards for the marking of rhinoceros horn and hunting of white rhinoceros for trophy hunting purposes were published in the government gazette in April 2012 and have since been implemented. The amendments have strengthened provisions relating to marking, the supervision of hunts, the transport of the horn subsequent to the hunt, reporting and monitoring, verification of hunters, and the taking of samples for DNA profiling, and have largely reduced the threats from pseudo-hunting.

While it is clear that rhino poaching has increased, so too has the focus and activities of the South African security forces in attempts to protect the rhino. Even so, poaching levels are inexorably rising to the detriment of the species and it can only be speculated what the levels of poached rhino might have been if additional measures had not been deployed. However, more resources are needed and agreements and strategies with neighbouring countries will be essential.

5.2 Intelligence

South Africa’s focus up to now has largely been on reactive strategies, where there have been extensive attempts to focus on escalating rhino poaching. However, it will be significantly more constructive if poachers can be halted before they get anywhere near rhinos. This will only come about through an increased focus on improved intelligence collection, its analysis and the resultant implementation of strategically focused activities. Moreover, a focus on prevention rather than ex post facto apprehension will allow the state and private sector to direct limited resources into areas that can have the most impact.

The analysis of intelligence should be undertaken by skilled intelligence data analysts, with information being fed back to the source institutions as part of the shared approach to information. This kind of effective coordination is a vital element of South African antipoaching strategy going forward. Intelligence feeding into this national database would include that collected from poached animals, information on syndicates and rhino horn markets. The development of useful preventative intelligence will require greater cooperation internationally. The current problems with the leaky Mozambique border and poor legal deterrents in Mozambique are providing the poaching syndicates the opportunities to operate freely and without fear.

5.3 Dehorning

The horn of a rhino grows approximately 5 cm annually and can be harvested safely as long as the procedure is undertaken properly (Emslie, 2012; Ferreira, 2012; Knight 2012). Microchipping and DNA sampling can be implemented at the time of de-horning. The horn is made of keratin, the same substance which forms human hair and nails.

A rhino uses its horns for territory defense, self-defense, dominance assertion through sparring, cows defending calves, mating and foraging. Black rhino use the anterior horn to pull high branches down to feed on. Rhino horns sometimes break in the wild but do grow back. Dehorning is unlikely to have negative long-term effects but it will be important toensure that all male rhino are dehorned at the same time, as a dehorned rhino will be at a considerable disadvantage in fighting (Ferreira, 2012).

Dehorning offers some defense against poaching but exposes the animal to some risk as it has to be chemically immobilized, and must be repeated on a regular basis as the horn grows. Humane dehorning, which ensures that the germinal layer is not damaged, leaves the base section intact for further growth. This base could weigh as much as a kilogram and at current prices still be attractive to poachers, thus still exposing the animal to a poaching threat. Poachers also kill dehorned rhinos to ensure they do not track the animal again, although notching of the feet (Lindsay & Taylor, 2011), which indicates in the spoor that the rhino being tracked is dehorned, can be a useful mechanism to deter this. When poachers operate at night, they cannot see if the rhino has a horn or not and may simply shoot.

The numbers of rhino to be dehorned in South Africa poses a logistical and budgetary challenge especially for the larger wide spread populations such as in the KNP or in iMfolozi Park. Each rhino has to be chemically immobilized and then dehorned and in some regions this will require helicopter darting due to the terrain. The darting, dehorning, micro-chipping and DNA sampling process takes between 30 minutes to one hour and costs approximately R8000/rhino after which blood and horn samples are sent to the national database for registration. Once the rhino has been dehorned, this procedure will need to be repeated every two to three years. Mortality from chemical capture is low at around one per cent.

To dehorn 10,000 rhino at a rate of eight rhino per day, will take approximately 1 000 days, and cost in the region of R84 million in 2012 ZAR (RIM calculations, 2012). The outcome of dehorning is a reduction in perceived value as well as rhino horn which, given that trade is illegal currently, is stockpiled. If kept in a few secure locations, protection for the stockpiles can be undertaken cost effectively.

Dehorning has been used as a strategy in Namibia and extensively in Zimbabwe where complete dehorning is preferred for small populations and strategic dehorning in larger populations. In South Africa, dehorning takes place in the private sector reserves and in Mpumalanga, but has not yet been used in SANParks or any other provincial reserve except for specific management purposes. In Namibia, post dehorning, not a single dehorned rhino was poached and in Mozambique, no dehorned rhinos have been killed. In Zimbabwe, dehorning coupled with translocation is believed to have significantly reduced poaching (Lindsay and Taylor, 2011) and in the Zimbabwean Lowveld Conservancies dehorned rhino have a 29.1 percent higher chance of survival than horned rhino (du Toit, 2011). Dehorning interventions work best in conjunction with other protective safety and security measures. Where dehorning has taken place without adequate security in place however, results have not been good. In Zimbabwe, in spite of complete dehorning in certain areas extensive poaching has continued and in some areas, entire populations have been wiped out (Lindsay & Taylor, 2011)

Re: Rhino Issue Manager Final Report 2012

5.6 Community Participation

Participation in rhino poaching activities within communities is largely driven by extreme poverty and lack of access to economic opportunity (Anti-Poaching Intelligence Group, 2012). Leaky borders and large number of illegal immigrants exacerbate the situation and poachers are recruited from amongst these, as well as from ex-freedom fighters from various neighbouring states. Such people are targets for international crime syndicates.

Formal training of community members where the community borders on or is part of the Park as rhino scouts has been suggested as an option and has already been implemented in Kenya with some success (Ferreira & Okita-Ouma, 2012) and is being implemented in some of the reserves on the KNPs western border. The involvement of communities is supported by the World Wildlife Fund of South Africa (WWF-SA) which recommends working with communities living close to rhinos to create buffer zones and to become “the first line of defence” against poaching (WWF-SA, 2012). Various models of counter-poaching such as that provided to RIM by Ntomeni Ranger Services, the International Anti-Poaching Foundation (IAPF) and supported by the Black Rhino Management Biodiversity Plan (Knight, 2011), have been mooted. The draft White Rhino Biodiversity Management Plan (Emslie, 2012) emphasises the importance of working with communities in rhino areas to gather information on an ongoing basis, to identify threats and to support anti-poaching activities. All models emphasise the need for good training and remuneration.

Involving communities in rhino horn farming with the scientific and technical assistance of the government Parks personnel partly as a security strategy is an option for consideration and is being requested by some communities such as the Balepye community which is calling for the removal of white rhino from Appendix ll of CITES and the introduction of legal trade.

5.7 Physical, Mechanical and Technology Options

DNA profiling of all rhino and micro-chipping of all horn and the maintenance of a centralised data base (RhODIS) are specific initiatives currently attempting to provide a baseline of information to be used for various monitoring purposes but which can also be used for forensic purposes to assist in rhino poaching investigations. It can be used to track rhino movements as well as to ensure legal hunting through a centralised permitting system.

Cyber tracking of rhino is possible using specific technology from a central control room located in areas of vulnerability (IAPF, 2012) while GPS and digital communications systems as well as the use of drones (Masie & Keats, 2012) are potential mechanisms to increase protection and reduce poaching. The type of drone recommended is a rotor-blade unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) which is silent and which operates as part of an extrasensory ecosystem. They have application in perimeter monitoring, patrolsupplementation and animal monitoring, and offer real-time reporting, population studies, fire watch and aerial photography capabilities

The use of technology to reduce poaching should occur in combination with basic ranger work (well trained & suitably equipped) and in particular the development of communities as anti-poaching rangers. The community training should be based upon a well-focussed and implemented NQF qualifications system where training and education occurs on an ongoing basis (IAPF, 2012). Most conservationists estimate there is a need for one ranger per 10 km2

(Knight, 2011).

Increased gate security and improved fencing and improved border security can all provide basic barrier methods which if well implemented, will contribute to better rhino security.

Participation in rhino poaching activities within communities is largely driven by extreme poverty and lack of access to economic opportunity (Anti-Poaching Intelligence Group, 2012). Leaky borders and large number of illegal immigrants exacerbate the situation and poachers are recruited from amongst these, as well as from ex-freedom fighters from various neighbouring states. Such people are targets for international crime syndicates.

Formal training of community members where the community borders on or is part of the Park as rhino scouts has been suggested as an option and has already been implemented in Kenya with some success (Ferreira & Okita-Ouma, 2012) and is being implemented in some of the reserves on the KNPs western border. The involvement of communities is supported by the World Wildlife Fund of South Africa (WWF-SA) which recommends working with communities living close to rhinos to create buffer zones and to become “the first line of defence” against poaching (WWF-SA, 2012). Various models of counter-poaching such as that provided to RIM by Ntomeni Ranger Services, the International Anti-Poaching Foundation (IAPF) and supported by the Black Rhino Management Biodiversity Plan (Knight, 2011), have been mooted. The draft White Rhino Biodiversity Management Plan (Emslie, 2012) emphasises the importance of working with communities in rhino areas to gather information on an ongoing basis, to identify threats and to support anti-poaching activities. All models emphasise the need for good training and remuneration.

Involving communities in rhino horn farming with the scientific and technical assistance of the government Parks personnel partly as a security strategy is an option for consideration and is being requested by some communities such as the Balepye community which is calling for the removal of white rhino from Appendix ll of CITES and the introduction of legal trade.

5.7 Physical, Mechanical and Technology Options

DNA profiling of all rhino and micro-chipping of all horn and the maintenance of a centralised data base (RhODIS) are specific initiatives currently attempting to provide a baseline of information to be used for various monitoring purposes but which can also be used for forensic purposes to assist in rhino poaching investigations. It can be used to track rhino movements as well as to ensure legal hunting through a centralised permitting system.

Cyber tracking of rhino is possible using specific technology from a central control room located in areas of vulnerability (IAPF, 2012) while GPS and digital communications systems as well as the use of drones (Masie & Keats, 2012) are potential mechanisms to increase protection and reduce poaching. The type of drone recommended is a rotor-blade unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) which is silent and which operates as part of an extrasensory ecosystem. They have application in perimeter monitoring, patrolsupplementation and animal monitoring, and offer real-time reporting, population studies, fire watch and aerial photography capabilities

The use of technology to reduce poaching should occur in combination with basic ranger work (well trained & suitably equipped) and in particular the development of communities as anti-poaching rangers. The community training should be based upon a well-focussed and implemented NQF qualifications system where training and education occurs on an ongoing basis (IAPF, 2012). Most conservationists estimate there is a need for one ranger per 10 km2

(Knight, 2011).

Increased gate security and improved fencing and improved border security can all provide basic barrier methods which if well implemented, will contribute to better rhino security.

Re: Rhino Issue Manager Final Report 2012

5.8 Farming

The IUCN African Rhinos Specialist Group (AfRSG) suggests three categories of rhino (Leader-Williams et al., 1997), wild, semi-wild and captive. Wild rhino move in large areas normally while semi-wild rhino live and breed in smaller areas 31 at a compressed density and require partial food supplementation. Captive rhino occur in much smaller areas, breeding is manipulated and they are fully husbanded with a total reliance upon food provision.

Captive populations act as a “safety net” should the depredations of poachers be successful in reducing wild rhino number to dangerously low levels (Emslie & Brooks, 1999) although high mortality rates and low reproductive rates can hamper speedy growth of captive populations. Some local rhino owners32 have however succeeded in achieving breeding growth rates of six per cent per annum. Looking after captive rhino can be more expensive than managing rhino in the wild (Leader-Williams et al., 1997). The captive keeping and breeding of rhino would involve captive populations being bred primarily for horn and husbanded in the same way as other animals which are bred and kept primarily for harvesting purposes.

Farming of Rhino has been mooted by many as a way of preventing poaching by providing farmed horn to meet demand, thus removing pressure on wild key and important populations. Captive breeding science and expertise would be needed to ensure proper habitat, handling, and good breeding rates. Black rhino have better breeding rates in captivity but higher mortality rates (Emslie & Brooks, 1999). Rhino farming is non-lethal in that horn can be harvested annually without damaging or killing the rhino and since rhino have a life span of between 35 and 50 years, rhino horn farming is likely to be a sound economic proposition. Trade partners will be needed as part of a strategy to re-introduce international trade, with China, Malaysia and Viet Nam suggested by stakeholders as possible options.

Some stakeholders argue that farmers are likely to breed rhino over time to produce an animal which is genetically selected for horn size thus changing the nature of the species. Others note that if this were to be the case, the parallel is similar to that of domestic cattle and wild buffalo where both exist for different purposes. The genetic integrity of the wild rhino however will not be compromised as long as the farmed and wild rhino remain distinct (Knight, 2012). The main argument against rhino farming remains that natural selection is discounted from the process and the species could proceed down a domestic animal trajectory. The challenge is to make sure the wild and captive populations remain distinct, with the incentive to still conserve animals over large landscapes in the wild.

5.9 Intensive Rhino Protection Zone

The setting up of an Intensive Rhino Protection Zone (IPZ) is an option where wild rhino range within a specific area, unfenced, and security and law enforcement staff are deployed in greater numbers to ensure higher levels of protection. This is a possibility where there are large areas to be managed resulting in security personnel being spread too thin to be effective against poaching (Emslie & Brooks, 1999).

5.10 Improved Enforcement of Security and Law

Increasing sniffer dogs at airports, improving training of customs officials, increased cooperation with international law enforcement and law enforcement agencies in the consumer countries, as well as increasing penalties and convictions for poaching are being implemented currently but the impact of this is not yet known. Poaching numbers continue to trend upwards and it seems likely that the numbers of rhino poached in South Africa (known) for the calendar year 2012, will reach over 500. The introduction of a crime awareness campaign, and better national coordination and organisation for implementation could yield improved use of resources if combined with other strategies which will ensure that the security forces are not spread too thinly. A proper assessment of law enforcement capacity at borders, customs areas, within ranges and in other critical areas, and the optimum training and redeployment of people and technology as a result, will be required. The deployment of a Rapid Reaction Force in areas where key and important populations are located would be highly constructive (WESSA, GRAA, GRU, 2012).

5.11 Other Initiatives

The President of Indonesia announced the (International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), 2012) the Year of the Rhino in 2012 as the Javan and Sumatran Rhinos are on the brink of extinction. The Indonesian government has established a Rhino Task Force consisting of international and national rhino experts which will help to ensure adequate monitoring of the rhino populations and which will ensure adequate protection for the remaining animals. This will also involve improving the integrity of rhino habitats and translocation of isolated individuals to safer areas. Kenya also declared 2012 as the Year of the Rhino to attempt to raise awareness and allocation of increased resources to rhino conservation and protection (Ferreira & Okita-Ouma, 2012). There is potential for a similar South African Presidential Project. The Endangered Wildlife Trust and the Rhino Response Project has set up a Rhino Orphanage which can accommodate, rehabilitate and restore to health orphaned calves35and many civil society organisations and private sector firms have set up and/or support specific rhino safety initiatives.

The IUCN African Rhinos Specialist Group (AfRSG) suggests three categories of rhino (Leader-Williams et al., 1997), wild, semi-wild and captive. Wild rhino move in large areas normally while semi-wild rhino live and breed in smaller areas 31 at a compressed density and require partial food supplementation. Captive rhino occur in much smaller areas, breeding is manipulated and they are fully husbanded with a total reliance upon food provision.

Captive populations act as a “safety net” should the depredations of poachers be successful in reducing wild rhino number to dangerously low levels (Emslie & Brooks, 1999) although high mortality rates and low reproductive rates can hamper speedy growth of captive populations. Some local rhino owners32 have however succeeded in achieving breeding growth rates of six per cent per annum. Looking after captive rhino can be more expensive than managing rhino in the wild (Leader-Williams et al., 1997). The captive keeping and breeding of rhino would involve captive populations being bred primarily for horn and husbanded in the same way as other animals which are bred and kept primarily for harvesting purposes.

Farming of Rhino has been mooted by many as a way of preventing poaching by providing farmed horn to meet demand, thus removing pressure on wild key and important populations. Captive breeding science and expertise would be needed to ensure proper habitat, handling, and good breeding rates. Black rhino have better breeding rates in captivity but higher mortality rates (Emslie & Brooks, 1999). Rhino farming is non-lethal in that horn can be harvested annually without damaging or killing the rhino and since rhino have a life span of between 35 and 50 years, rhino horn farming is likely to be a sound economic proposition. Trade partners will be needed as part of a strategy to re-introduce international trade, with China, Malaysia and Viet Nam suggested by stakeholders as possible options.

Some stakeholders argue that farmers are likely to breed rhino over time to produce an animal which is genetically selected for horn size thus changing the nature of the species. Others note that if this were to be the case, the parallel is similar to that of domestic cattle and wild buffalo where both exist for different purposes. The genetic integrity of the wild rhino however will not be compromised as long as the farmed and wild rhino remain distinct (Knight, 2012). The main argument against rhino farming remains that natural selection is discounted from the process and the species could proceed down a domestic animal trajectory. The challenge is to make sure the wild and captive populations remain distinct, with the incentive to still conserve animals over large landscapes in the wild.

5.9 Intensive Rhino Protection Zone

The setting up of an Intensive Rhino Protection Zone (IPZ) is an option where wild rhino range within a specific area, unfenced, and security and law enforcement staff are deployed in greater numbers to ensure higher levels of protection. This is a possibility where there are large areas to be managed resulting in security personnel being spread too thin to be effective against poaching (Emslie & Brooks, 1999).

5.10 Improved Enforcement of Security and Law

Increasing sniffer dogs at airports, improving training of customs officials, increased cooperation with international law enforcement and law enforcement agencies in the consumer countries, as well as increasing penalties and convictions for poaching are being implemented currently but the impact of this is not yet known. Poaching numbers continue to trend upwards and it seems likely that the numbers of rhino poached in South Africa (known) for the calendar year 2012, will reach over 500. The introduction of a crime awareness campaign, and better national coordination and organisation for implementation could yield improved use of resources if combined with other strategies which will ensure that the security forces are not spread too thinly. A proper assessment of law enforcement capacity at borders, customs areas, within ranges and in other critical areas, and the optimum training and redeployment of people and technology as a result, will be required. The deployment of a Rapid Reaction Force in areas where key and important populations are located would be highly constructive (WESSA, GRAA, GRU, 2012).

5.11 Other Initiatives

The President of Indonesia announced the (International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), 2012) the Year of the Rhino in 2012 as the Javan and Sumatran Rhinos are on the brink of extinction. The Indonesian government has established a Rhino Task Force consisting of international and national rhino experts which will help to ensure adequate monitoring of the rhino populations and which will ensure adequate protection for the remaining animals. This will also involve improving the integrity of rhino habitats and translocation of isolated individuals to safer areas. Kenya also declared 2012 as the Year of the Rhino to attempt to raise awareness and allocation of increased resources to rhino conservation and protection (Ferreira & Okita-Ouma, 2012). There is potential for a similar South African Presidential Project. The Endangered Wildlife Trust and the Rhino Response Project has set up a Rhino Orphanage which can accommodate, rehabilitate and restore to health orphaned calves35and many civil society organisations and private sector firms have set up and/or support specific rhino safety initiatives.

Re: Rhino Issue Manager Final Report 2012

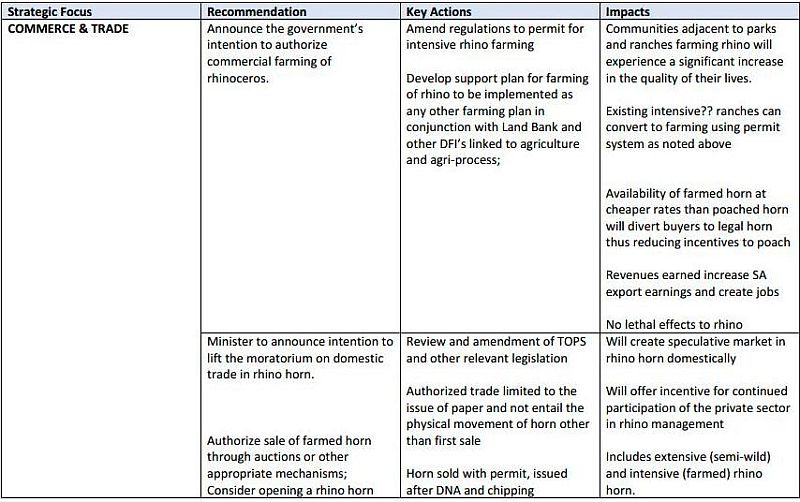

7.1 Elements of Commerce

7.1.1 Hunting

Hunting of white rhino in South Africa was re-introduced in 1968 and is considered to have contributed positively to biological management, the generation of revenue for conservation and increased incentives to promote effective population growth (Milliken & Shaw, 2012). The hunting and related industries are estimated to employ approximately 70 000 people in South Africa, largely in rural areas, and include trackers, professional hunters, veterinarians, and capture specialists. From 1995 to 2011, estimates are that approximately 1 300 white rhino have been legally hunted in South Africa (Milliken & Shaw, 2012). Historically, hunters were of South African, European and North American origin, but since 2003, with the resurgence in demand for rhino horn in certain Asian countries, more hunters from these areas have been seeking permits.

Organised and legal hunting is viewed by many conservationists as a useful tool in a portfolio of population management tools which has the additional advantage of raising much needed funds for the conservation of the species. The South African hunting permitting system has however been abused by criminal private sector elements as well as corrupt public sector officials, to the detriment of the rhino . Recent abuse of the hunting system in order to acquire the horn as a “hunting trophy” and thus a legitimate export, led to South Africa introducing stricter measures, including the requirement that a person must submit proof that he / she is a bona fide hunter. South Africa furthermore requested Vietnam to confirm that rhino trophies exported to Vietnam since 2010 are still in the hunters’ possession. Until an official confirmation is received from Vietnam, no further applications to hunt rhino are considered if the applicant’s country of usual residence is Vietnam. However, syndicates now simply spread applications for permits in such a way as to spread the nationality profile, as the horn is still a primary target. An improvement in the hunting permitting system40 is urgently needed to prevent further depredations.

7.1.2 Farming

In the view of some stakeholders, farming of rhino for horn is a non-lethal process with no negative outcomes for the species. As such, it is dissimilar to lethal farming processes such as beef farming, or other lethal harvesting processes such as the killing of bears for their bile, and the killing of elephants for their ivory. Rhino do not need to be killed for their horn. Some argue that farming will change the genetic focus of breeding, and that commercial farmers will adapt rhino to ensure a larger horn and this is quite probable over time. However, farming will not affect the genetics of wild rhino as long as the populations do not mix and should reduce motivation to poach wild rhino. Current private rhino owners firmly support a process whereby they can harvest horn and legally sell it in order to offset costs of rhino herd protection and management and there are practical opportunities for community involvement in farming processes.

Commercial game farming or game ranching involves the breeding of game for a financial return. Game farming is intensive, and the animals are kept in relatively small spaces with emphasis on production, welfare and management. Game ranching has the same focus, but the animals live in extensive and spacious environments and there is emphasis on biodiversity and eco-viability as well as production, welfare and management.

Community participation (Balepye Community, 2012; Nomtshongwana, 2012) is seen by stakeholders to be an important element of rhino conservation with the benefit of being linked to sustainable economic empowerment. Impoverished communities living within and near parks and reserves need jobs and income and are susceptible to offers of money for assistance with poaching. Such communities could be developed to farm rhino in partnership with the private sector and the Parks, resulting in a significantly improved socioeconomic status for these communities. As an example, if South African rhino owners donated 4,800 rhino to the communities, and worked with the communities to increase the number at 5 per cent per annum, the communities would own 29 000 rhino by 2037. If the 4 800 rhino were to be distributed to 120 communities, at 40 rhino per community (requiring approximately 600 hectares of land) then 50 kg of horn could be harvested and sold annually. This would represent, at current prices, an income of over US$ 2 million per annum. Clearly the same applies to commercial farmers who may choose to farm rhino (white). At an assumed price of US$ 40 000/kg, 5kg/horn set, and assuming 500 rhino poached by end December 2012, South Africa will have lost revenue of USD 40 million which, if white rhino were farmed, could have instead been used in local economies. Loon (2012) notes that if rhino are more valuable alive than dead, there will be incentive to keep them alive. Currently there is no economic incentive for communities living close to rhino ranges to keep them alive. It is legal in South Africa to farm and ranch rhino but there is no incentive to do so as the horn is the most valuable part of the rhino, and this cannot be traded. Thus, owning rhino currently means that costs significantly outweigh benefits.

7.1.1 Hunting

Hunting of white rhino in South Africa was re-introduced in 1968 and is considered to have contributed positively to biological management, the generation of revenue for conservation and increased incentives to promote effective population growth (Milliken & Shaw, 2012). The hunting and related industries are estimated to employ approximately 70 000 people in South Africa, largely in rural areas, and include trackers, professional hunters, veterinarians, and capture specialists. From 1995 to 2011, estimates are that approximately 1 300 white rhino have been legally hunted in South Africa (Milliken & Shaw, 2012). Historically, hunters were of South African, European and North American origin, but since 2003, with the resurgence in demand for rhino horn in certain Asian countries, more hunters from these areas have been seeking permits.

Organised and legal hunting is viewed by many conservationists as a useful tool in a portfolio of population management tools which has the additional advantage of raising much needed funds for the conservation of the species. The South African hunting permitting system has however been abused by criminal private sector elements as well as corrupt public sector officials, to the detriment of the rhino . Recent abuse of the hunting system in order to acquire the horn as a “hunting trophy” and thus a legitimate export, led to South Africa introducing stricter measures, including the requirement that a person must submit proof that he / she is a bona fide hunter. South Africa furthermore requested Vietnam to confirm that rhino trophies exported to Vietnam since 2010 are still in the hunters’ possession. Until an official confirmation is received from Vietnam, no further applications to hunt rhino are considered if the applicant’s country of usual residence is Vietnam. However, syndicates now simply spread applications for permits in such a way as to spread the nationality profile, as the horn is still a primary target. An improvement in the hunting permitting system40 is urgently needed to prevent further depredations.

7.1.2 Farming

In the view of some stakeholders, farming of rhino for horn is a non-lethal process with no negative outcomes for the species. As such, it is dissimilar to lethal farming processes such as beef farming, or other lethal harvesting processes such as the killing of bears for their bile, and the killing of elephants for their ivory. Rhino do not need to be killed for their horn. Some argue that farming will change the genetic focus of breeding, and that commercial farmers will adapt rhino to ensure a larger horn and this is quite probable over time. However, farming will not affect the genetics of wild rhino as long as the populations do not mix and should reduce motivation to poach wild rhino. Current private rhino owners firmly support a process whereby they can harvest horn and legally sell it in order to offset costs of rhino herd protection and management and there are practical opportunities for community involvement in farming processes.

Commercial game farming or game ranching involves the breeding of game for a financial return. Game farming is intensive, and the animals are kept in relatively small spaces with emphasis on production, welfare and management. Game ranching has the same focus, but the animals live in extensive and spacious environments and there is emphasis on biodiversity and eco-viability as well as production, welfare and management.

Community participation (Balepye Community, 2012; Nomtshongwana, 2012) is seen by stakeholders to be an important element of rhino conservation with the benefit of being linked to sustainable economic empowerment. Impoverished communities living within and near parks and reserves need jobs and income and are susceptible to offers of money for assistance with poaching. Such communities could be developed to farm rhino in partnership with the private sector and the Parks, resulting in a significantly improved socioeconomic status for these communities. As an example, if South African rhino owners donated 4,800 rhino to the communities, and worked with the communities to increase the number at 5 per cent per annum, the communities would own 29 000 rhino by 2037. If the 4 800 rhino were to be distributed to 120 communities, at 40 rhino per community (requiring approximately 600 hectares of land) then 50 kg of horn could be harvested and sold annually. This would represent, at current prices, an income of over US$ 2 million per annum. Clearly the same applies to commercial farmers who may choose to farm rhino (white). At an assumed price of US$ 40 000/kg, 5kg/horn set, and assuming 500 rhino poached by end December 2012, South Africa will have lost revenue of USD 40 million which, if white rhino were farmed, could have instead been used in local economies. Loon (2012) notes that if rhino are more valuable alive than dead, there will be incentive to keep them alive. Currently there is no economic incentive for communities living close to rhino ranges to keep them alive. It is legal in South Africa to farm and ranch rhino but there is no incentive to do so as the horn is the most valuable part of the rhino, and this cannot be traded. Thus, owning rhino currently means that costs significantly outweigh benefits.

Re: Rhino Issue Manager Final Report 2012

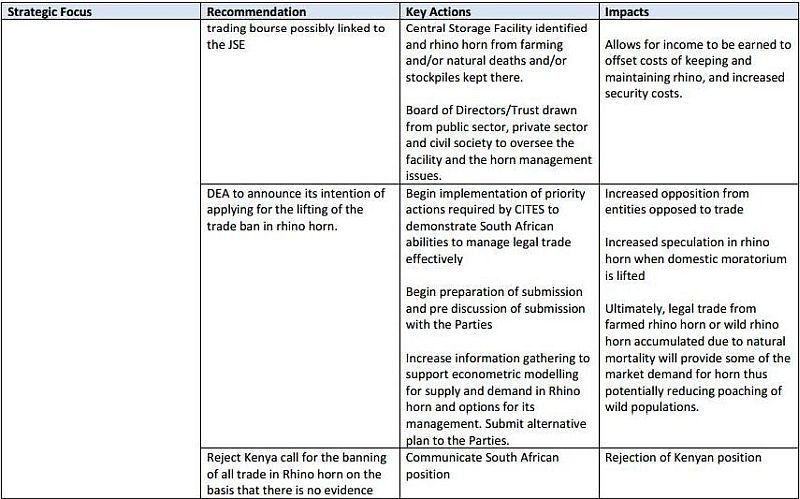

7.1.3 Trading

Demand for rhino is vested in the live animals, used for stocking other ranges, zoos, and the like, and the horn, used in traditional medicine and crafts.

Live rhino sales of surplus rhino to approved destinations generated approximately ZAR 236 million for the period 2008 to 2011 (Milliken & Shaw, 2012). This represents an important source of conservation revenue for the various conservation agencies charged with maintaining biodiversity and protecting species in South Africa.

Horns that occur due to natural deaths are required to be declared, registered and become part of the national stockpile where they are micro-chipped and loaded on the central database. More recently, some private sector owners and some public officials have been found to have concealed and sold such horns to illegal traders in defiance of South African law. This was one of the key factors which determined the implementation of a moratorium on the sale of rhino horn inside South Africa which is still in force. Illegal trade has increased dramatically since 2003 with the involvement of international and national organised crime syndicates who use globally sophisticated supply chains to focus on illegal trade in high value items. This includes drug trafficking, human trafficking and trafficking in arms. Due to a reported retail price of between US$ 40,000 and US$ 60 000/kg (Martin, 2012) per animal rhino horn has become an attractive proposition for the syndicates. This has resulted in more sophisticated and efficient poaching techniques such as the use of specific drugs and high calibre weaponry instead of the more traditional poaching approaches (Milliken & Shaw, 2012). It has also dramatically increased the need for and the costs of protection. The South African moratorium on domestic trade in rhino horn, acquired from dead rhino, has had the unintended consequence of shifting the attention to poaching live rhino for horn as the horn cannot be bought legally.

In 1990, fourteen rhino were poached in but by 2011 this had increased to 448. From January to December 2012, 633 rhino were poached and estimates suggest that the final number of poached rhino in 2012 will be over 650 (Knight, 2012). This is occurring in the context of significant increases in protection, improved law enforcement and other attempts to protect the rhino population where the arrest rate in 2012 was more than double that of 2011 and bail is now rarely allowed.

The cost of increasing protection services for rhino has resulted in fewer resources available for other species, and in the face of declining government budgets for Parks and the insistence that they become more self-sustaining, a serious financial problem for many. This is not only important for State entities, but also within the private sector which holds just under 25 per cent of South Africa’s rhinos. Those struggling with huge cost increases to protect the rhino call for various forms of trade to be legalised.

State conservation agencies use the funds raised from live white rhino sales to help subsidise conservation efforts or to buy additional conservation land. White rhino sales have been the biggest contributor to total turnover at Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife (EKZNW) game auctions, both live and catalogue, accounting for 74,9% of total turnover from 2008 to July 2011. The average price achieved per white rhino from EKZNW and SANParks in 2011 is just over R230 000/rhino.

The call is for trade in rhino horn as a result of natural death and trade in the stockpiles accumulated by the private and public sector owners to be permitted in order to cover the costs of maintaining the species44. Further calls have been made to commercialise rhino horn and permit for the harvesting of horn from live rhino. This would have the double effect of reducing the incentive to poach a rhino with no horn this preserving the animal’s life, as well as providing an income through farming in that the horn can be harvested annually and sold as part of a legal trade system. Spin offs of this would include sustainable job creation, and a high value new export industry for South Africa. Value added activities could be implemented prior to export. Communities which might otherwise engage in poaching support, could farm rhino for their own benefit. However, many animal rights and animal welfare organisations45, some with global reach and large budgets, are anti-trade, believing that it stimulates cruelty to animals, and/or causes or contributes to the extinction of species, although there is no evidence of this for rhino.

7.1.4 Tourism

Rhino are included amongst the big five which can now only be seen in Africa. This attracts tourists who come to see wild animals in a natural range. The value of game viewing based tourism to South Africa in 2011 is not known but there is little doubt that the ability to view rhino is a constituent element of the attraction.

Demand for rhino is vested in the live animals, used for stocking other ranges, zoos, and the like, and the horn, used in traditional medicine and crafts.

Live rhino sales of surplus rhino to approved destinations generated approximately ZAR 236 million for the period 2008 to 2011 (Milliken & Shaw, 2012). This represents an important source of conservation revenue for the various conservation agencies charged with maintaining biodiversity and protecting species in South Africa.

Horns that occur due to natural deaths are required to be declared, registered and become part of the national stockpile where they are micro-chipped and loaded on the central database. More recently, some private sector owners and some public officials have been found to have concealed and sold such horns to illegal traders in defiance of South African law. This was one of the key factors which determined the implementation of a moratorium on the sale of rhino horn inside South Africa which is still in force. Illegal trade has increased dramatically since 2003 with the involvement of international and national organised crime syndicates who use globally sophisticated supply chains to focus on illegal trade in high value items. This includes drug trafficking, human trafficking and trafficking in arms. Due to a reported retail price of between US$ 40,000 and US$ 60 000/kg (Martin, 2012) per animal rhino horn has become an attractive proposition for the syndicates. This has resulted in more sophisticated and efficient poaching techniques such as the use of specific drugs and high calibre weaponry instead of the more traditional poaching approaches (Milliken & Shaw, 2012). It has also dramatically increased the need for and the costs of protection. The South African moratorium on domestic trade in rhino horn, acquired from dead rhino, has had the unintended consequence of shifting the attention to poaching live rhino for horn as the horn cannot be bought legally.

In 1990, fourteen rhino were poached in but by 2011 this had increased to 448. From January to December 2012, 633 rhino were poached and estimates suggest that the final number of poached rhino in 2012 will be over 650 (Knight, 2012). This is occurring in the context of significant increases in protection, improved law enforcement and other attempts to protect the rhino population where the arrest rate in 2012 was more than double that of 2011 and bail is now rarely allowed.

The cost of increasing protection services for rhino has resulted in fewer resources available for other species, and in the face of declining government budgets for Parks and the insistence that they become more self-sustaining, a serious financial problem for many. This is not only important for State entities, but also within the private sector which holds just under 25 per cent of South Africa’s rhinos. Those struggling with huge cost increases to protect the rhino call for various forms of trade to be legalised.

State conservation agencies use the funds raised from live white rhino sales to help subsidise conservation efforts or to buy additional conservation land. White rhino sales have been the biggest contributor to total turnover at Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife (EKZNW) game auctions, both live and catalogue, accounting for 74,9% of total turnover from 2008 to July 2011. The average price achieved per white rhino from EKZNW and SANParks in 2011 is just over R230 000/rhino.

The call is for trade in rhino horn as a result of natural death and trade in the stockpiles accumulated by the private and public sector owners to be permitted in order to cover the costs of maintaining the species44. Further calls have been made to commercialise rhino horn and permit for the harvesting of horn from live rhino. This would have the double effect of reducing the incentive to poach a rhino with no horn this preserving the animal’s life, as well as providing an income through farming in that the horn can be harvested annually and sold as part of a legal trade system. Spin offs of this would include sustainable job creation, and a high value new export industry for South Africa. Value added activities could be implemented prior to export. Communities which might otherwise engage in poaching support, could farm rhino for their own benefit. However, many animal rights and animal welfare organisations45, some with global reach and large budgets, are anti-trade, believing that it stimulates cruelty to animals, and/or causes or contributes to the extinction of species, although there is no evidence of this for rhino.

7.1.4 Tourism

Rhino are included amongst the big five which can now only be seen in Africa. This attracts tourists who come to see wild animals in a natural range. The value of game viewing based tourism to South Africa in 2011 is not known but there is little doubt that the ability to view rhino is a constituent element of the attraction.

Re: Rhino Issue Manager Final Report 2012

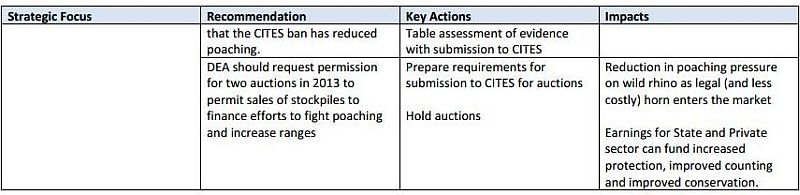

8.1.1 Rhino and CITES

Currently all black rhino are categorised as critically endangered and are listed in Appendix l of CITES, with South Africa and Namibia each permitted a hunting quota for five black rhino per annum. White rhino are categorised as threatened and are also listed in Appendix l, other than South African and Swaziland, which have annotated partial down-listings for live sales to appropriate and acceptable destinations and for the export of hunting trophies. No trade in loose horn or any other specimens of rhino, for commercial purposes, is currently allowed. In order to permit trade in rhino horn, using the standard CITES process, the following are required:

Two thirds of the Parties (signatories to CITES) will need to agree to the proposal, and some areas, such as the EU, vote as a bloc, making it essential to have their support;

Consultation with other range States of the species is a requirement – refer to Resolution Conf 8.21

Consequently, lobbying and education will be required prior to any such proposal to ensure that the reasons for the South African proposal for down-listing are well understood and appreciated;

Any such application will need to be accompanied by reliable and valid population information as well as information pertaining to the proposed trading system and the monitoring and enforcement of this, the identification and approval of the trading partner, and a system for the application of funds raised in horn trade to conservation;

No proposal will be considered unless a) there is a national integrated permitting and data base system in place (to confirm legal origin) and b) a full list of stockpiles with DNA referencing complete;

The biological and trade criteria47 agreed by the Parties must be met for the down-listing of white rhino. No down-listing of black rhino will be permitted at this point as the species is not at the point where it will meet the criteria.

The supporting statement from South Africa must include species and populations characteristics, status and trends, threats, utilisation and trade, review of legal and management systems and species management plans.

If a process similar to the African elephant is followed, a CITES Panel of Experts (PoE) could then be convened to verify the information provided in the proposal with reference to the viability and sustainability of the population and threats; South Africa’s ability to monitor the population; the effectiveness of current anti-poaching measures; South Africa’s ability to control the trade and; whether law enforcement is sufficient and effective, inter alia. Subsequent to information gathering, the PoE will report to the COP and a two thirds majority vote will be needed to approve the request.

The Parties meet every three years and the next meeting is in Thailand in March 2013. At this point, South Africa is unprepared to make any submission to amend its annotation to include trade in rhino horn. However, there is provision in the CITES agreement for representations to be made by a Party for changes to the listings outside of/in the time in between, the Conferences of the Parties (COP) meetings.

Currently all black rhino are categorised as critically endangered and are listed in Appendix l of CITES, with South Africa and Namibia each permitted a hunting quota for five black rhino per annum. White rhino are categorised as threatened and are also listed in Appendix l, other than South African and Swaziland, which have annotated partial down-listings for live sales to appropriate and acceptable destinations and for the export of hunting trophies. No trade in loose horn or any other specimens of rhino, for commercial purposes, is currently allowed. In order to permit trade in rhino horn, using the standard CITES process, the following are required:

Two thirds of the Parties (signatories to CITES) will need to agree to the proposal, and some areas, such as the EU, vote as a bloc, making it essential to have their support;

Consultation with other range States of the species is a requirement – refer to Resolution Conf 8.21

Consequently, lobbying and education will be required prior to any such proposal to ensure that the reasons for the South African proposal for down-listing are well understood and appreciated;