BY STASJA KOOT - 12 FEBRUARY 2019 - STASIA KOOT

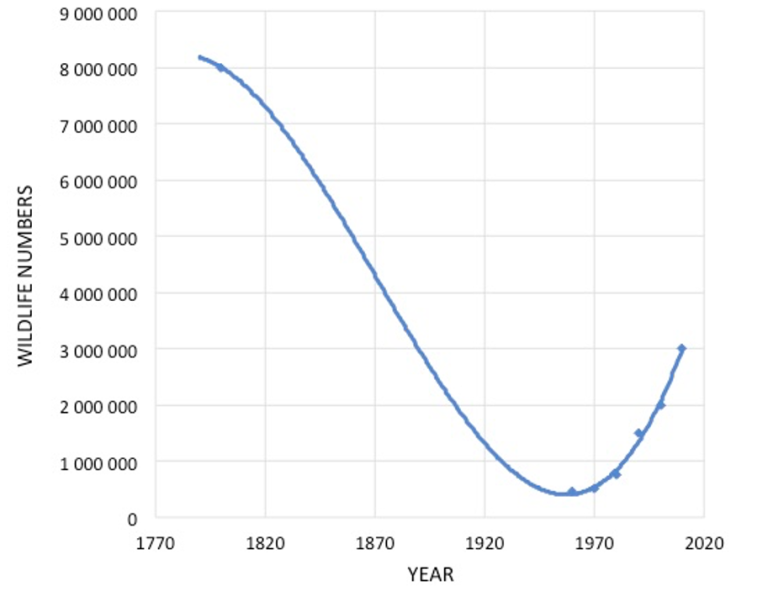

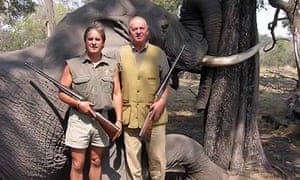

Recent years have shown an increase in the, often heated, debate on trophy hunting, with some important developments taking place in southern Africa. To name just some that have accelerated the debate: In 2012, pictures of King Juan Carlos of Spain emerged in which he posed in front of his trophies, an elephant and two African buffaloes. As a result of the public outcry that followed, the King was dismissed as the honorary president of WWF Spain, which is ironic when realising that various WWF offices in southern Africa support trophy hunting in the name of conservation and development. Other important developments have been a ban on trophy hunting in Botswana in 2013, a very controversial hunt of a black rhino in Namibia for US$350,000 in 2015 and the infamous illegal hunt of Cecil the Lion in Zimbabwe in 2015. Royal connections of this hobby for the wealthy have a long history and continue today. The Duke of Cambridge, Prince William, for example, currently speaks out against the trophy hunting ban in Botswana.

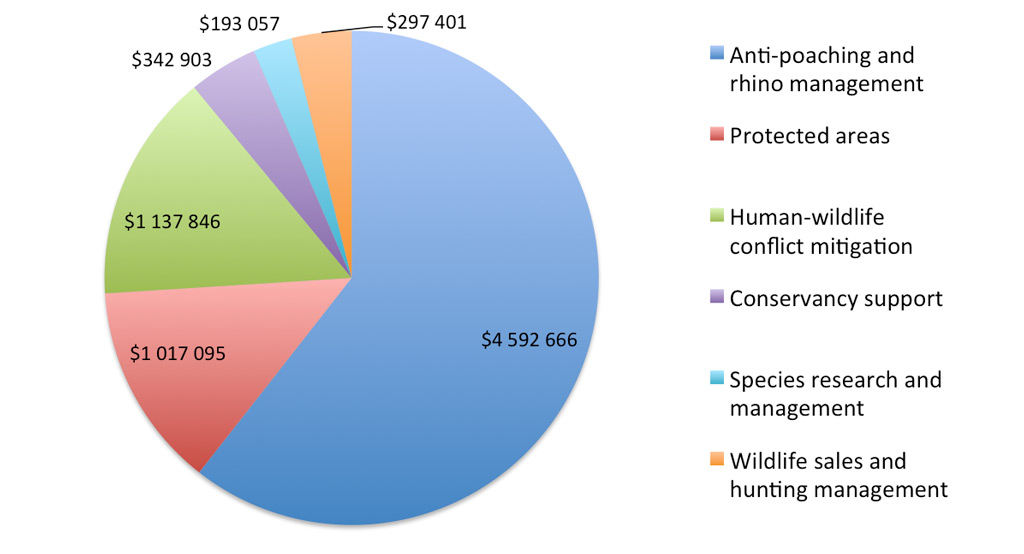

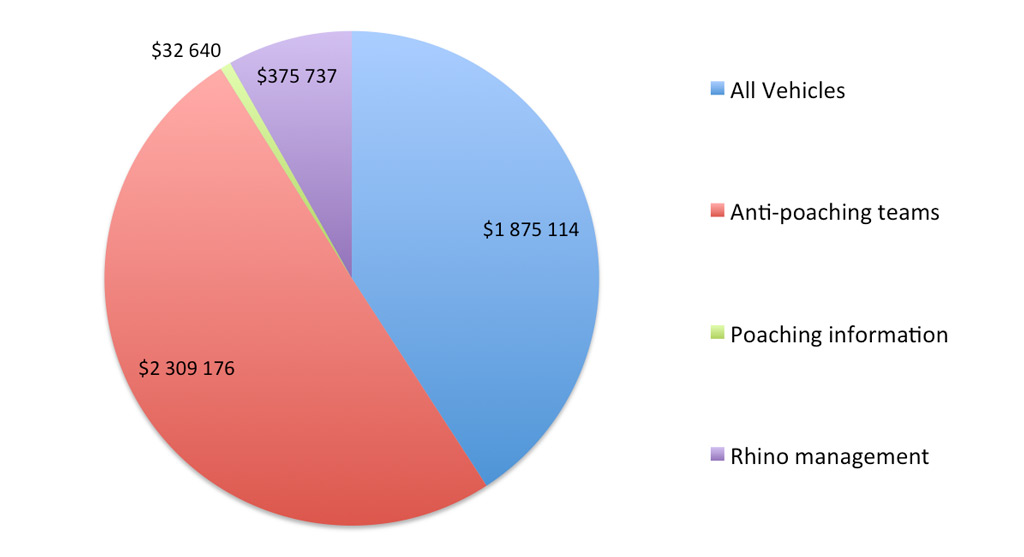

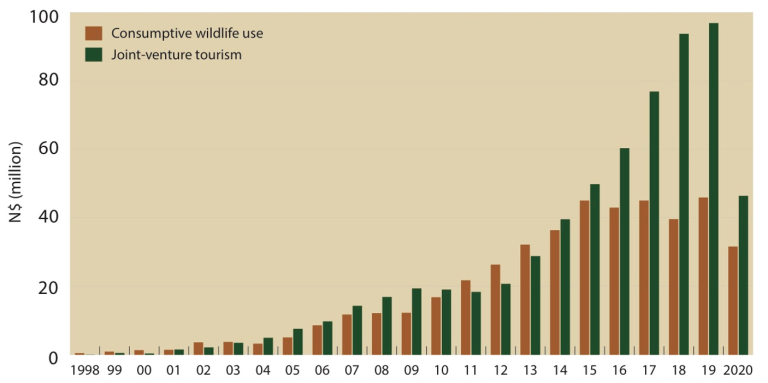

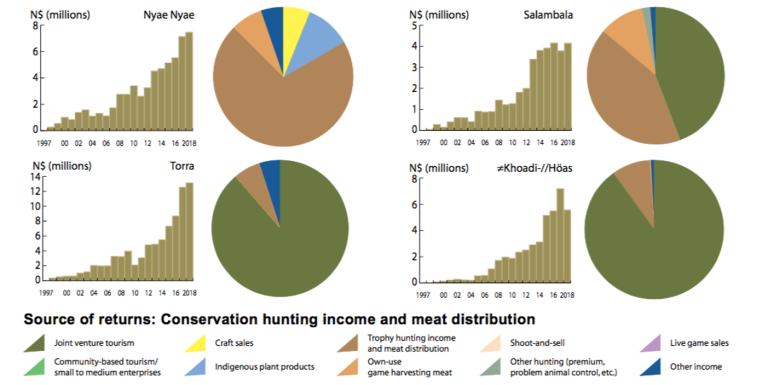

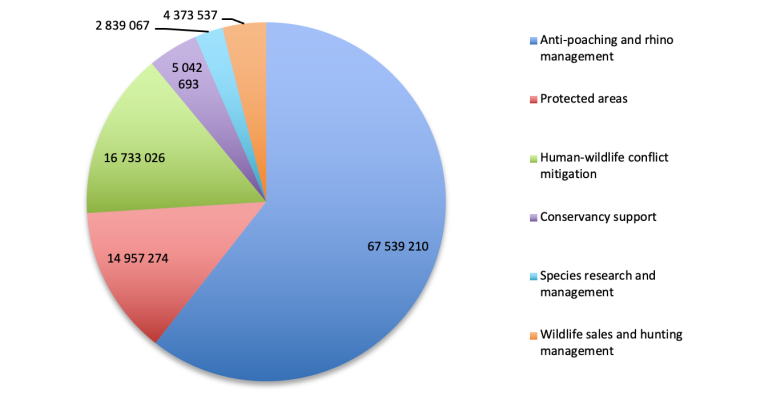

Proponents of trophy hunting argue that it is good for conservation and for the development of marginalised people. In Namibia, a flagship country for so-called ‘community-based natural resource management’ (CBNRM), trophy hunting plays a crucial role in this programme; in CBNRM, local groups are targeted to contribute to conservation and to live together with the wildlife. In return, they receive economic and material benefits, such as jobs in tourism and conservation and the meat from the hunts. Moreover, to keep CBNRM financially healthy, a requirement is a continuous stream of income, and trophy hunting provides for such large revenues because the amounts that hunters pay can be enormous; in the Namibian Nyae Nyae Conservancy, one of the cases described in a recent paper of mine (Koot 2019), the price for a 14-day hunt of one elephant costs US$ 80,000,-.

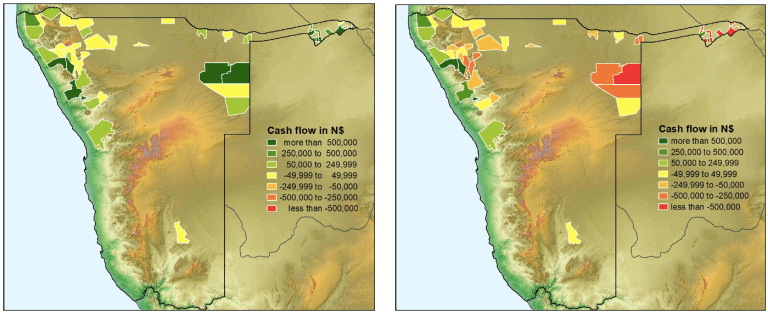

So in Namibia, as in many other countries, conservationists, hunting operators and the Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) all argue that the hunting industry is very important not only for the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP), but especially for the development of marginalised rural populations. However, according to Economists at Large (2013) only 0,27% of the Namibian GDP is constituted by trophy hunting, and most of the revenues go to hunting operators, airlines, governments and tourism facilities. So how serious should we take the argument that ‘economic benefits’ are being created in Namibia for poor rural populations? This argument is problematic for various reasons; it masks differences within communities that are presented as if they are static, homogeneous entities and it masks power relations between segments of these communities and outsiders (such as NGOs, hunting operators, donors and government officials). I do not deny that economic benefits at times exist, but by focusing only on these as the success of trophy hunting, other dynamics are covered up, especially those in the social and human domain. Moreover, such a neoliberal discourse accounts for the idea that the local people do not yet understand how to do ‘proper’ conservation (MacDonald 2005), and therefore need to be taught how things work, strongly resembling colonial structures and power relations, based on paternalistic ideas about moral edification.

Elephant skull in Bwabwata National Park OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

San realities

An interesting group in this regard is the San (or Bushmen) in Namibia. As ‘former’ hunter-gatherers some San groups are today involved in CBNRM initiatives in which trophy hunting plays a crucial role. Take, for example, the Khwe San who live in Bwabwata National Park. When some Khwe tried to establish relationships with impatient, wealthy, white hunting operators, this was considered ‘bribery’ by a local NGO working on CBNRM and the MET, because officially contact with hunters is not allowed when the selection process for a tender is not yet finished. However, on the ground such negotiations often take place already informally. In another example, the Ju/’hoansi San of the Nyae Nyae Conservancy showed how the group that worked with one particular hunting operator felt stressed, suppressed and humiliated by the operator, all for a very low salary. When I asked them why they would not simply leave the job, the answer was that there are only few job opportunities in the Nyae Nyae Conservancy. Indeed, partly due to the CBNRM programme their possibilities to create other types of livelihoods (e.g. through agriculture), are very limited, and the distribution of meat has always been a problem because of the wide dispersal of the settlements in Nyae Nyae. According to the Ju/’hoansi labourers, WWF played a crucial role in choosing this particular hunting operator because he would pay the highest bid for the tender (and thus create the largest income for the CBNRM programme). This does not necessarily mean that jobs always have a bad meaning for people, since in another example with a subcontractor in Nyae Nyae people enjoy their jobs and even receive some extra benefits. Then again, the question remains if hunting operators are indeed the right people to be involved in development; a hunter in Bwabwata recently explained that the ‘lazy’ Khwe employees are mostly a hindrance to his business and he has no interest in community development.

Dried elephant meat in the Nyae Nyae Conservancy OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Altogether, jobs can be received for good or ill, but to look at jobs and simply call them ‘benefits’ is not enough; it masks structural issues beyond and within labour relations and potential exploitation. Therefore, I argue for an expansion of the trophy hunting debate beyond economic ‘benefits’ (Koot 2019), for example by using environmental psychologist James Gibson’s (1979) theoretical framework of ‘social affordances’, in which the interactions between organisms create meaning (instead of pre-decided ‘benefits’). By doing so, local perceptions, meanings, multiple experiences and power relations are addressed, and the larger human domain is taken into account (of which the ‘economy’ is only a part). In fact, reducing ‘development’ only to ‘economic benefits’ creates a simplistic image of a much more complex reality. But this is not something that is only done in trophy hunting and it is of much larger importance in environmental issues globally; trophy hunting is a good example of what Robert Fletcher (2010) calls ‘neoliberal environmentality’, which entails a situation in which the environment is shaped based on economic incentives with the aim of economic growth (based on market mechanisms) only.

The role of science

What is worrying, is that a large stream of scientific papers that address CBNRM and trophy hunting in Namibia as a golden bullet, are written by practitioners from a variety of organisations whose work is to promote exactly this model (see, for example, Angula et al 2018; Naidoo et al 2016)! The papers originate from organisations such as WWF Namibia, WWF US, and the Nambian Association of CBNRM Support Organisations (NACSO). Interestingly, they do not provide any information about the researchers’ position in relation to their respondents and, not surprisingly, the findings were overall favouring trophy hunting and CBNRM more generally, showing mostly how ‘successful’ the programme is (cf. Büscher 2014). The potential conflict of interest is, of course, important to be addressed in such cases and it is therefore necessary that researchers, including those originating in more ‘positivist’ traditions, explain their researcher position and reflect upon this when relevant. Moreover, the ‘success’ is all too easily taken over by the conservation movement and the private sector or parties representing their interest, such as the Namibian Chamber of the Environment (see, e.g. Brown 2017) and, especially, the Namibian Professional Hunting Association (NAPHA). The latter represents the interests of the trophy hunting industry, and has now fully embraced such scientific papers. For example, in their Position Paper NAPHA bluntly states:

“I shall leave it to an internationally respected conservation organisation, the WWF, to point out the benefits that trophy hunting brings to Communal Conservancies in Namibia through a study undertaken by them between 1998 and 2013. The title of this study is “Complimentary [sic] benefits of tourism and hunting to communal conservancies in Namibia”. It must be stressed that this study piece, unlike many of the pseudo – studies available on the internet, has been peer reviewed and independently verified.” (NAPHA 2016)

The paper that is being referred to by NAPHA has been written by WWF practitioners (Naidoo et. al. 2016) and addresses only economic benefits. It remains to be seen what research is meant with “the pseudo – studies available on the internet”, but the way in which NAPHA positions itself and uses ‘science’ to promote their own activities shows only a small part of the global trophy hunting lobby. Moreover, it shows that national and international power relations these days matter more than ever, and this includes scientific research that has the potential to feed neoliberal environmentality. I hope that the Duke of Cambridge is aware of the important realities on the ground that local communities experience and that he keeps this in mind when he negotiates to reinstate trophy hunting in Botswana. My gut feeling though, tells me he is just another puppet in a much bigger game.

Read original article: https://stasjakoot.com/2019/02/12/troph ... aa-ixRHdsk