By Tiara Walters• 30 July 2020

(Photo: Unsplash/Tatyana Eremina)

Pet owners are blissfully unaware that their social media darlings may massacre some 30 million in local prey annually.

Think your little Felix is no troublemaker because it seems he never leaves your property? Think again.

While photos of your pet cat live large on social media, and rake in “loves and wows”, the real deal’s likeness has been filmed on the edges of Table Mountain National Park, helping wreck indigenous wildlife, one animal at a time.

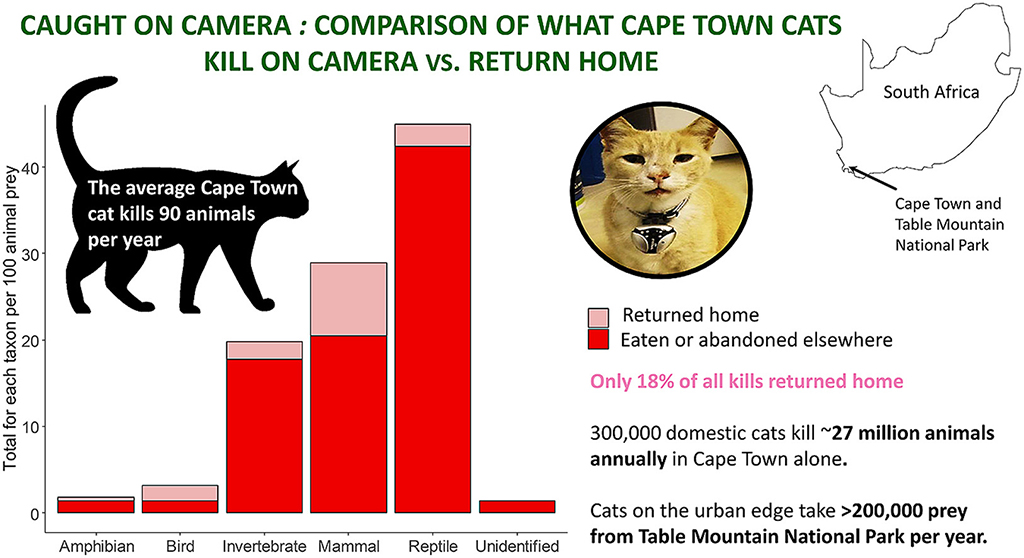

A single Cape Town house cat destroys about 90 animals a year — yet, less than 20% of these kills are ever returned home, a group of South African scientists has revealed.

Most casualties butchered by this army of feline felons are native animals, already under pressure from tanking ecotourism revenues and environmental factors. Fires fanning through the park each summer, like the March 2020 blaze on Lion’s Head, is just one example of such a pressure. It burnt out several nearby cars and transformed 60 hectares of wild habitat into a shade of midnight dystopia.

Kitties padding around the urban edges of the park are probably claiming at least 200,000 prey from the reserve each year, the study estimates — this from a 265km² area meant to protect more biodiversity than in the entire United Kingdom.

In a new paper published in the journal Global Ecology & Conservation, the scientists have also provided a new snapshot of the extent of these impacts, not just on park borders, but into the very heart of urban areas.

Ninety animals over a whole year — or less than eight prey items a month, say. As an isolated statistic that sounds somewhat harmless. Until one considers there are 300,000 domestic cats prowling through the Mother City alone, probably slaying nearly 30 million animals annually, the scientists have said.

When the owner’s away, the cat will play

The paper monitored behaviour by strapping “KittyCams” to cats whose humans volunteered them for the research, which represents multiple studies conducted over a decade by institutions including the University of Cape Town (UCT) and the South African National Biodiversity Institute (Sanbi).

“We have used the current estimates of Cape Town’s population [4.6-million] to estimate the number of cats [in the city], as it’s likely to have increased over the last decade — even allowing for almost no cat ownership in townships,” study lead author Colleen Seymour told Daily Maverick. She is a biodiversity specialist with UCT and Sanbi. (Feral cats were excluded.)

Co-author Robert E Simmons said that the study provides a “much more robust assessment of predation in Cape Town and Table Mountain National Park”.

“We have expressed the results in prey captured per year — 90 animals per average cat — which makes more sense than daily predation used previously,” said Simmons, a UCT-based research associate.

In recent years, scientific literature from Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the US and, to a lesser extent, Europe, have published on domestic cat predation.

The “vast majority” of these, however, relied on questionnaires rather than camera footage, which kept owners ignorant of what their cats attacked and/or ate beyond property borders.

“They have thus not only underestimated predation by [up to] 5.5- fold, they may have misrepresented the type of prey being taken,” explained Simmons.

Across species surveyed, the KittyCam showed that around 80% of the death tally never made it back to the cat’s residential turf. The lion’s share was devoured on the spot or abandoned altogether — and all this under the cover of night, making it even harder to witness Felix’s trail of destruction.

“This answers some of those pet owners who maintain their cats never kill anything,” Simmons said.

Startling species smorgasbord

Dividing the study’s cats into two gangs, the scientists found that moggies on the urban edge caught the same number of animals as their counterparts deep in the suburbs.

However, victims hunted down by the “deep urban” gang were not exactly the same as unfortunates pounced upon by the “urban edge” gang near park borders.

In fact, native fauna were by far the biggest losers of the killing spree.

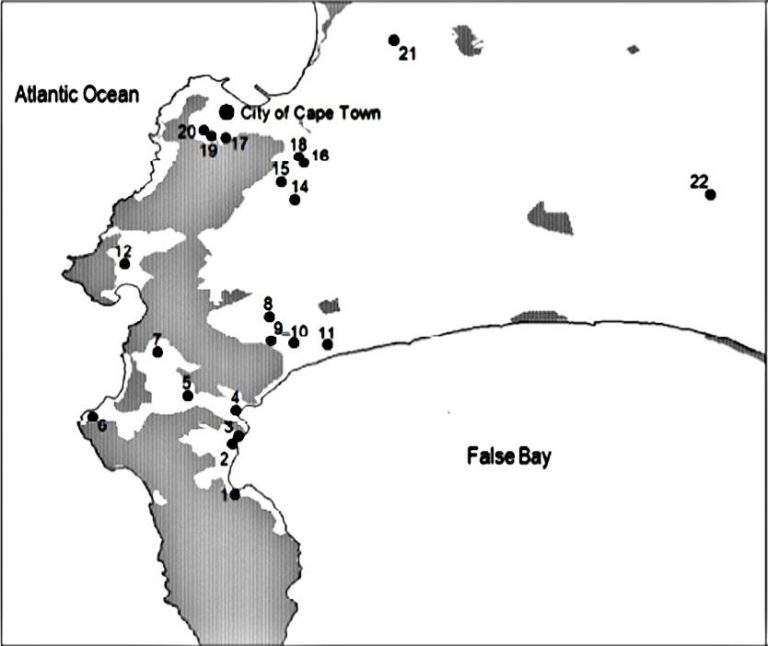

Upwards of 2,200 cats are estimated to include the park within their home range.

KittyCam study sites (1-22) across Cape Town. Protected areas, mostly in Table Mountain National Park, are in grey. (Credit: ‘Caught on camera — impacts of urban domestic cats on wild prey in an African city and neighbouring protected areas’ by Colleen L. Seymour, Robert E. Simmons, Frances Morling, Sharon T. George, Koebraa Peters, M. Justin O’Riain/Global Ecology & Conservation)

Snaking from Signal Hill in the north to Cape Point in the south, this protected reserve is designed to be a refuge for species such as the endangered western leopard toad, the vulnerable Cape rain frog and the endemic orange-breasted sunbird.

Each of these species is found nowhere else on Earth but in the Western Cape: “All were killed by the cats in our study,” the paper said.

Exotic species, in fact, represented a paltry 17% of animals nailed by the deep urban gang. These made up an even smaller margin of the urban edge gang’s menu: that is, just 6%.

“Many people own cats to keep alien pests under control,” noted Simmons. “So the costs to native species is relatively high compared to the benefits of owning a good mouser.”

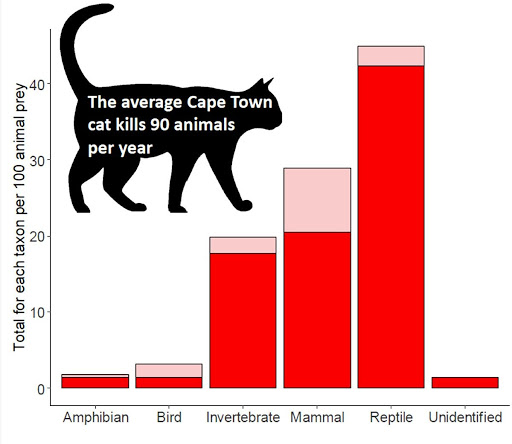

Tabby eat-out favourites were not, as one might expect, mammals or even birds.

Native reptiles, “coincident with peak cat hunting times”, were the most popular (particularly endemics) and they were largely consumed instantly. Mammals came in second, followed by invertebrates, birds and, finally, amphibians.

Conversely, mammals comprised only a quarter of prey, but here more than half of kills were dragged in through cat flaps, spirited over window sills and plonked within walking distance of owners’ feet.

“There is a funny side to this research, too,” recalled co-author Justin O’Riain of UCT’s Institute for Communities and Wildlife in Africa. “For the most part, owners remembered to close doors to bathrooms and bedrooms. But there were some hilarious moments when the owners either forgot or realised midway through an act of showering, say, that the cat watching them had a camera on.”

Some “shooing” and “scattering of confused” cats ensued.

“Such footage was duly removed prior to analyses,” he pointed out. “But the importance of citizens and the sacrifices they and their cats made in the success of this research cannot be overemphasised.”

Paws for thought: will cat owners, authorities listen?

But that’s where the kitten around ends.

Especially during these times of social isolation and distancing, cats are kept by many as indispensable companions — particularly to people living in small spaces such as apartments.

Cats are also instinctive roamers.

Confining them indoors would not only be a hard sell, it would also be cruel, well-known South African butterfly expert Steve Woodall wrote on his Facebook page. His comments captured the tension between pet welfare and maintaining species diversity.

“We live next to a nature reserve. I love cats as pets, but I cannot ignore this… please don’t tell me to build catios [enclosed cat patios] and keep the cat indoors — that is as abhorrent to me as caging a bird,” he wrote. “We humans are going to have to modify our behaviour if we are serious about preserving biodiversity.”

Finding useful – and socially acceptable – ways of intervening in the scale of predation partly comes down to working with how cat brains are wired.

Ross Wanless is a Cape Town-based ornithologist who has done extensive modelling of cat predation in island ecologies. The term “domestic” in the context of house cats, he told Daily Maverick, is a misnomer. Many, if not most, are still feral ramblers at heart.

“Cats have never fully bought into domestication the way dogs have… The ease with which they return to independence, without human subsidies of food and shelter,” he said, “speaks to the fact that perhaps cats have domesticated humans. Imagine a chihuahua trying to hack it in the bush. Cats do it all the time.”

No matter that cats at home are fed.

“Despite supplemental feeding, domestic cats actively hunt and kill prey even when prey populations are low,” the study said.

Wanless said the findings were a “very robust confirmation of what many researchers had long known or suspected”.

Hot-favourite items on Cape Town cat eat-out menus. (Credit: ‘Caught on camera — impacts of urban domestic cats on wild prey in an African city and neighbouring protected areas’ by Colleen L. Seymour, Robert E. Simmons, Frances Morling, Sharon T. George, Koebraa Peters, M. Justin O’Riain/Global Ecology & Conservation)

In a popular article, Wanless relates the tragic story of Tibbles, the unquenchable cat of Stephens Island in New Zealand’s Cook Strait.

“The Stephens Island wren, a bird with a world range of less than 3km², was ‘discovered’ by Tibbles, the lighthouse keeper’s cat, in 1894,” he writes. “By the end of the same year, Tibbles had hunted the wren to extinction.”

Tibbles ranks among other tabbies that have caused numerous island extinctions, the Cape Town study notes. Although the extinct island species had not evolved defences against the introduced predators, “exceptionally high densities of domestic cats suggest that continental wildlife, accustomed to predation, are unlikely to escape”, according to the research.

Apart from killing or leaving indigenous wildlife with severe injuries, cat predation also removes animals that perform roles in the urban or wild ecosystem.

Even basic stalking behaviour may disrupt ecological functioning. The study cites several threats, such as:

- Influencing local species behaviour and reproductive success;

- Competing with local predators such as caracal, Cape grey mongoose, small spotted genet, jackal buzzard, the endangered black harrier (domestic cat densities are 330 times that of wild African felids); and

- Transmitting disease to native animals, as “exemplified by the deaths of five of the world’s remaining 130 Florida panthers”, which “died of feline leukaemia virus originating from a domestic cat”.

To avoid a similar fate for Mother City species, the study recommends:

- Developing urban bylaws that “restrict cat ownership in urban-edge properties”;

- Introducing 360m-2,400m buffers next to “environmentally sensitive areas. These should be cat-free or the cats contained within properties”;

- Installing catios as a “sustainable solution”; and

- Using sonic and ultrasonic deterrents; collar-mounted “pounce protectors”; wide, brightly coloured collars to alert birds and reptiles; and keeping cats indoors, particularly at night.

The paper pours cold water on the idea of fitting bells to collars.

“The majority of prey in our study area are unlikely to hear a bell and those that can may not associate it with danger,” it says.

For all its recommendations and new insights, it is likely that not even this study gained a handle on the full degree of local cat predation. A black cat crossing the road may be a harbinger of as much bad luck for native species as the Cape Town study’s remaining questions.

“The batteries on our KittyCams precluded videoing cat activities beyond 2.30am (being recharged at about 6am),” the paper concedes. “As technology improves with better battery life, estimates should become more accurate and our estimates of the impacts of cats may increase.”

For being one among few world cities with immediate borders on a protected area, Cape Town is fairly unique. Even so, across the US, for instance, billions of individual indigenous animals succumb to domestic cat claws every year. Talk about midnight dystopia: in fire-ravaged Australia, it’s 460 million.

“Even low-frequency visits by cats into an experimental area in Australia caused the extinction of an indigenous rodent,” the study says.

And, as Cape Town’s human population grows, the same is likely to be true for the city’s cats.

Commenting on the study, Alderman Marian Nieuwoudt said that “the City notes the findings with interest”. The City of Cape Town’s mayoral committee member for spatial planning and environment, Nieuwoudt added that the City “is fully supportive of using sound scientific research and best practice from around the world to try and manage the impact of domestic cats on our indigenous fauna”.

Park authorities were not available for comment by the time of publication. DM