Killing the Holy Ghost: Inside the R145bn plan that would destroy the Limpopo River

- Peter Betts

- Posts: 3084

- Joined: Fri Jun 01, 2012 9:28 am

- Country: RSA

- Contact:

Re: Killing the Holy Ghost: Inside the R145bn plan that would destroy the Limpopo River

So who gets the Spin off from the Tenders

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67589

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Killing the Holy Ghost: Inside the R145bn plan that would destroy the Limpopo River

Why has Limpopo dumped its biodiversity protection plan into a dark hole?

The largest baobab tree in the Mapungubwe National Park. (Photo: Gallo Images / Go! / Villiers Steyn)

By Tony Carnie | 02 Apr 2023

Is it because the Vhembe bioregional plan has been squashed – or held up deliberately – to smooth the passage of the controversial Chinese-led plan to develop a massive new steel plant and special economic zone in the heart of Vhembe district?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

South Africa has an abundance of beautiful places, each judged subjectively through the eyes of the beholders.

But who would argue that the far northern tip of the country is one of the most spectacular and beautiful spaces nationwide?

This is the Vhembe district, that largely open, wild landscape immediately south of the Limpopo River. A place of bright orange sunsets in the heart of baobab country, balancing rocks, abandoned stone citadels and a wealth of plants and animals. Cheetahs, elephants, pangolins and many smaller creatures or vegetation types are found nowhere else in the world.

Right at the top of the district, where our national border meets Zimbabwe and Botswana, lies the Mapungubwe National Park and World Heritage Site. The park takes its name from an ancient kingdom established here in about 900 AD. Later, it became one of the most powerful inland trading settlements in Africa, until its demise in the 13th century.

Mapungubwe National Park, on the South African border with Zimbabwe and Botswana. (Photo: Gallo Images / Media 24)

Vhembe’s eastern corner also incorporates the top section of the famous Kruger National Park. Further south, the landscape is dominated by the heights of the Soutpansberg mountains which includes the sacred waters of Lake Fundudzi, reputed to be protected by a python god.

So, not really any surprise that the unique 3,010,100-hectare surface area of the Vhembe district was recognised as a Unesco biosphere reserve 14 years ago. The Vhembe Biosphere Reserve is part of the World Network of Biosphere Reserves that includes 738 sites in 134 countries. The broad aim of biosphere reserves is to “foster the harmonious integration of people and nature for sustainable development”.

Limpopo has five districts – Waterberg, Mopani, Capricorn, Sekhukhune and Vhembe. Over recent years, environmental and heritage experts have developed planning tools for all five to safeguard the most sensitive areas from the worst excesses of development – outside formally protected areas such as Kruger and Mapungubwe.

Known as “bioregional plans”, they incorporate a detailed assessment of an area’s biological status and are used in the environmental impact assessment process and by spatial and land-use planners to inform land-use decisions at municipal level.

The Mapungubwe Koppie in the Mapungubwe National Par. (Photo: Gallo Images / Media 24)

The plans are also used by the Limpopo Department of Economic Development, Environment and Tourism (Ledet) to inform development and land-use planning decisions.

All of the Limpopo bioregional plans have been approved and gazetted… except for the Vhembe district.

Why would that be?

Is it because the Vhembe bioregional plan has been squashed – or held up deliberately – to smooth the passage of the controversial Chinese-led plan to develop a massive new steel plant and special economic zone in the heart of Vhembe district?

Significantly, Limpopo’s environmental affairs division falls under the wing of a larger department responsible for economic development, pushing strongly for the new special economic zone.

Our Burning Planet sent several questions to Ledet spokesperson Zaid Kalla to find out why there is such a long hold-up in approving the Vhembe bioregional plan.

We also asked him to comment on allegations by local stakeholders that the plan was stalled due to direct political interference from senior Ledet/Limpopo government officials who fear that the Vhembe bioregional plan is in direct conflict with the proposed Musina Makhado Special Economic Zone (MMSEZ).

Dodging the direct question about political interference, Kalla insisted that the bioregional plan had not been “abandoned at all” and was still being used in “its current status” to inform land-use planning, environmental assessment and authorisations.

Kalla suggested that the Vhembe plan had simply been delayed because the “process (of) gazetting (is) still to be done by the department”.

What unique reasons could there be for delaying the gazetting of the Vhembe plan, when Ledet confirmed that it had received no written objections to the draft version published in 2019?

Before exploring further answers – in the absence of more cogent explanations from Ledet – a brief explainer about the purpose of bioregional plans may be useful.

The Vhembe Biosphere Reserve, covering more than 3 million hectares of land in Limpopo, is one of more than 700 such reserves globally. (Photo: Vhembe Biosphere Reserve)

The Limpopo River winds through the top section of the Vhembe district. (Photo: Tony Carnie)

In September 2018, the then acting national minister of environmental affairs, Derek Hanekom, wrote a letter to the then Limpopo government MEC in charge of Ledet, Seaparo Sekoati.

Hanekom congratulated Sekoati for his province’s decision to develop a bioregional plan for Vhembe district, which he described as a “significant accomplishment” and “a stepping stone towards the fulfilment of the requirements of our conservation objectives as outlined in the Constitution”: namely to protect and preserve biodiversity for current and future generations.

Noting that the declaration of all new bioregions and bioregional plans require the approval of the national environment minister, Hanekom signalled his official consent to adopting the bioregional plan.

On 30 August, 2019 this draft bioregional plan was published in the Limpopo provincial gazette, giving the public 30 days to comment on the proposal. No formal objections were received. The path was clear.

Remarkably, however, the plan suddenly sank without trace – possibly into the depths of Lake Fundudzi, or was consigned to the back of a dusty cupboard.

A map of the Vhembe-Bioregional-plan, showing the position of the proposed special economic zone and colour-coded biodiversity features of the region. National and provincial parks are in dark green, while critical biodiversity areas and ecological support areas are shown in a lighter shade. Critical biodiversity areas (CBAs) are sites that are deemed essential to meet national biodiversity targets. The majority of these areas in the Vhembe district are classified as CBA 1, which can be considered irreplaceable to meet biodiversity targets. Those areas falling within CBA 2 are considered optimal for achieving biodiversity targets. Ecological Support Areas (ESAs) are areas that are considered important for supporting the ecological functioning of both CBAs and protected areas and for meeting biodiversity targets and connectivity pathways. This category has also been split into ESA1 (areas still in a largely natural state) while ESA2 areas are no longer intact but potentially retain significant importance for ecological processes and landscape connectivity.

‘Conflict’ with coal

Sadly, there is no mystery about the reasons for this, suggests Lauren Liebenberg, founder of the Living Limpopo group which has been campaigning against industrial mega projects such as the Musina-Makhado SEZ and uncontrolled coal mining in Limpopo.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone: The desperate battle to defuse Limpopo’s climate bomb

“The only conclusion that can be reached for the delay in approving the bioregional plan is that Ledet is aware that it is in conflict with the MMSEZ project. The Chinese-controlled special economic zone – as well as many of the proposed coal mining projects in the region – fall within areas that are designated as critical biodiversity areas or ecological support areas.

“There are very, very few places left in the world that are still in a natural state,” says Liebenberg. “Vhembe is one of those special places that have so much potential for visionary plans to be put in place now to protect biodiversity for future generations – before it is too late.” DM/OBP

The largest baobab tree in the Mapungubwe National Park. (Photo: Gallo Images / Go! / Villiers Steyn)

By Tony Carnie | 02 Apr 2023

Is it because the Vhembe bioregional plan has been squashed – or held up deliberately – to smooth the passage of the controversial Chinese-led plan to develop a massive new steel plant and special economic zone in the heart of Vhembe district?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

South Africa has an abundance of beautiful places, each judged subjectively through the eyes of the beholders.

But who would argue that the far northern tip of the country is one of the most spectacular and beautiful spaces nationwide?

This is the Vhembe district, that largely open, wild landscape immediately south of the Limpopo River. A place of bright orange sunsets in the heart of baobab country, balancing rocks, abandoned stone citadels and a wealth of plants and animals. Cheetahs, elephants, pangolins and many smaller creatures or vegetation types are found nowhere else in the world.

Right at the top of the district, where our national border meets Zimbabwe and Botswana, lies the Mapungubwe National Park and World Heritage Site. The park takes its name from an ancient kingdom established here in about 900 AD. Later, it became one of the most powerful inland trading settlements in Africa, until its demise in the 13th century.

Mapungubwe National Park, on the South African border with Zimbabwe and Botswana. (Photo: Gallo Images / Media 24)

Vhembe’s eastern corner also incorporates the top section of the famous Kruger National Park. Further south, the landscape is dominated by the heights of the Soutpansberg mountains which includes the sacred waters of Lake Fundudzi, reputed to be protected by a python god.

So, not really any surprise that the unique 3,010,100-hectare surface area of the Vhembe district was recognised as a Unesco biosphere reserve 14 years ago. The Vhembe Biosphere Reserve is part of the World Network of Biosphere Reserves that includes 738 sites in 134 countries. The broad aim of biosphere reserves is to “foster the harmonious integration of people and nature for sustainable development”.

- What unique reasons could there be for delaying the gazetting of the Vhembe plan, when Ledet confirmed that it had received no written objections to the draft version published in 2019?

Limpopo has five districts – Waterberg, Mopani, Capricorn, Sekhukhune and Vhembe. Over recent years, environmental and heritage experts have developed planning tools for all five to safeguard the most sensitive areas from the worst excesses of development – outside formally protected areas such as Kruger and Mapungubwe.

Known as “bioregional plans”, they incorporate a detailed assessment of an area’s biological status and are used in the environmental impact assessment process and by spatial and land-use planners to inform land-use decisions at municipal level.

The Mapungubwe Koppie in the Mapungubwe National Par. (Photo: Gallo Images / Media 24)

The plans are also used by the Limpopo Department of Economic Development, Environment and Tourism (Ledet) to inform development and land-use planning decisions.

All of the Limpopo bioregional plans have been approved and gazetted… except for the Vhembe district.

Why would that be?

Is it because the Vhembe bioregional plan has been squashed – or held up deliberately – to smooth the passage of the controversial Chinese-led plan to develop a massive new steel plant and special economic zone in the heart of Vhembe district?

Significantly, Limpopo’s environmental affairs division falls under the wing of a larger department responsible for economic development, pushing strongly for the new special economic zone.

Our Burning Planet sent several questions to Ledet spokesperson Zaid Kalla to find out why there is such a long hold-up in approving the Vhembe bioregional plan.

We also asked him to comment on allegations by local stakeholders that the plan was stalled due to direct political interference from senior Ledet/Limpopo government officials who fear that the Vhembe bioregional plan is in direct conflict with the proposed Musina Makhado Special Economic Zone (MMSEZ).

Dodging the direct question about political interference, Kalla insisted that the bioregional plan had not been “abandoned at all” and was still being used in “its current status” to inform land-use planning, environmental assessment and authorisations.

Kalla suggested that the Vhembe plan had simply been delayed because the “process (of) gazetting (is) still to be done by the department”.

1. Draft bioregional plans for all five districts of Limpopo have been published. The plans forWaterberg, Mopane, Capricorn and Sekhukune have all been approved and gazetted - but the planfor Vhembe has not been gazetted. Is this correct?.

Response: Yes

2. As noted above, the draft Vhembe Bioregional Plan was published in the provincial gazette inAugust 2019 giving a 30-day period for public comment. Three and a half years later, however, theVhembe plan remains unpublished. Can LEDET kindly elaborate on the reasons for this long delay,and any unique factors that distinguish the Vhembe plant from the other four district plans thatwere approved and gazetted?

Response: All five bioregional plans in Limpopo were developed as provided for in the Biodiversity Act,so they can be used to facilitate biodiversity conservation in priority areas outside the protected areasnetwork.

3. If any formal objections/concerns were raised by stakeholders in relation to the Vhembe planduring the 30-day comment period, what was the nature of these objections/concerns and whichspecific bodies/interest groups raised them?

Response: No objections were raised by stakeholders. Only enquiries regarding the purpose ofpublishing the plan and that was dealt with directly with the concerned stakeholder.

4. Some stakeholders have drawn the conclusion that the Vhembe bioregional plan has beendeliberately squashed/suppressed due to direct political interference from senior LEDET/Limpopogovernment officials because of perceptions that the Vhembe bioregional plan is in direct conflictwith LEDA's proposed Musina Makhado Special Economic Zone (MMSEZ). What is LEDET'scomment/response to this allegation?

Response: The Vhembe Bioregional Plan at its current status is still used to inform land-use planning,environmental assessment and authorisations and natural resource management by a range of sectorsincluding LEDET whose decisions impact on biodiversity. The bioregional plan does not replace theneed for site assessments, particularly for Environmental Impact Assessment.

5. Is the draft Vhembe bioregional plan still under discussion or has it been abandoned entirely?

Response: It is not abandoned at all, as indicated above, it is one of the planning tools used in theprovince to inform decision making.

6. If the former, at what point have these discussions reached? Can LEDET give an indication of whenit may be gazetted by the MEC? And should it be published, what are the most significantamendments (if any)?

Response: No amendments the process the gazetting still to be done by the department.

7. If the latter, who gave instructions for the Vhembe plan to be discontinued - and what were thereasons for such decision?

Response: None

What unique reasons could there be for delaying the gazetting of the Vhembe plan, when Ledet confirmed that it had received no written objections to the draft version published in 2019?

Before exploring further answers – in the absence of more cogent explanations from Ledet – a brief explainer about the purpose of bioregional plans may be useful.

The Vhembe Biosphere Reserve, covering more than 3 million hectares of land in Limpopo, is one of more than 700 such reserves globally. (Photo: Vhembe Biosphere Reserve)

The Limpopo River winds through the top section of the Vhembe district. (Photo: Tony Carnie)

In September 2018, the then acting national minister of environmental affairs, Derek Hanekom, wrote a letter to the then Limpopo government MEC in charge of Ledet, Seaparo Sekoati.

Hanekom congratulated Sekoati for his province’s decision to develop a bioregional plan for Vhembe district, which he described as a “significant accomplishment” and “a stepping stone towards the fulfilment of the requirements of our conservation objectives as outlined in the Constitution”: namely to protect and preserve biodiversity for current and future generations.

Noting that the declaration of all new bioregions and bioregional plans require the approval of the national environment minister, Hanekom signalled his official consent to adopting the bioregional plan.

On 30 August, 2019 this draft bioregional plan was published in the Limpopo provincial gazette, giving the public 30 days to comment on the proposal. No formal objections were received. The path was clear.

Remarkably, however, the plan suddenly sank without trace – possibly into the depths of Lake Fundudzi, or was consigned to the back of a dusty cupboard.

A map of the Vhembe-Bioregional-plan, showing the position of the proposed special economic zone and colour-coded biodiversity features of the region. National and provincial parks are in dark green, while critical biodiversity areas and ecological support areas are shown in a lighter shade. Critical biodiversity areas (CBAs) are sites that are deemed essential to meet national biodiversity targets. The majority of these areas in the Vhembe district are classified as CBA 1, which can be considered irreplaceable to meet biodiversity targets. Those areas falling within CBA 2 are considered optimal for achieving biodiversity targets. Ecological Support Areas (ESAs) are areas that are considered important for supporting the ecological functioning of both CBAs and protected areas and for meeting biodiversity targets and connectivity pathways. This category has also been split into ESA1 (areas still in a largely natural state) while ESA2 areas are no longer intact but potentially retain significant importance for ecological processes and landscape connectivity.

‘Conflict’ with coal

Sadly, there is no mystery about the reasons for this, suggests Lauren Liebenberg, founder of the Living Limpopo group which has been campaigning against industrial mega projects such as the Musina-Makhado SEZ and uncontrolled coal mining in Limpopo.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone: The desperate battle to defuse Limpopo’s climate bomb

“The only conclusion that can be reached for the delay in approving the bioregional plan is that Ledet is aware that it is in conflict with the MMSEZ project. The Chinese-controlled special economic zone – as well as many of the proposed coal mining projects in the region – fall within areas that are designated as critical biodiversity areas or ecological support areas.

“There are very, very few places left in the world that are still in a natural state,” says Liebenberg. “Vhembe is one of those special places that have so much potential for visionary plans to be put in place now to protect biodiversity for future generations – before it is too late.” DM/OBP

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67589

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Killing the Holy Ghost: Inside the R145bn plan that would destroy the Limpopo River

There are people who are willing to "sell" their country for some kind of economical interest against something which is our heritage and has been there for millions of years and will still be there for all the years to come, if left alone

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67589

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Killing the Holy Ghost: Inside the R145bn plan that would destroy the Limpopo River

UNDP moves to scrap support for ‘risky’ R165bn Limpopo heavy industry zone

Illustrative image: The United Nations Development Programme signed a Memorandum of Understanding with South African officials in March 2022 to support the Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone in Limpopo. A UNDP watchdog has now advised the body to withdraw its backing for the heavy industry plan. (Photos: Supplied and UNDP/MMSEZ press announcement)

By Tony Carnie | 25 Feb 2024

A United Nations internal watchdog unit has advised its biggest development aid agency to scrap an agreement backing the development of a R165-billion heavy industry zone in Limpopo. Citing the risk of significant reputational harm to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the agency’s New York-based Social and Environmental Compliance Unit (SECU) has recommended the immediate cancellation of an agreement signed two years ago to support the controversial Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone (MMSEZ).

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

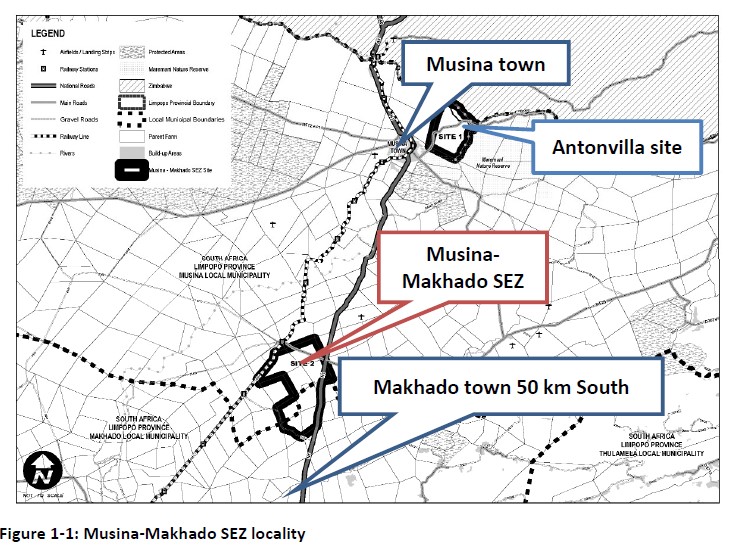

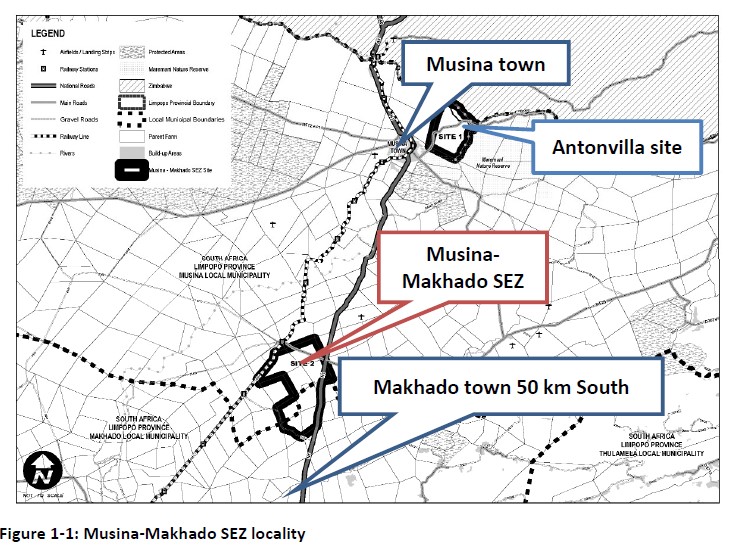

The project, driven by the state-owned Limpopo Economic Development Agency (LEDA), was initially touted as a R165-billion scheme supported by a consortium of Chinese investors. It would entail building a major 8,000ha heavy industry hub roughly halfway between the towns of Musina and Makhado next to the coal- and mineral-rich Soutpansberg region.

A map showing the boundaries of the proposed MMSEZ. (Photo: MMSEZ environmental impact report)

It would feature up to 20 new industrial projects clustered together in a single tax- and duty-free zone. This would include a new iron and steel plant, a ferrochrome plant, a chrome plating plant; an agro-chemical and petrochemical manufacturing plant; mineral beneficiation; a new Smart City and a logistics cluster projected to attract foreign direct investment. It would apparently create between 21,000 to 53,000 jobs.

However, the project has drawn strong criticism from several quarters for a variety of reasons – including concerns about massive water demands from heavy industry in a water-scarce region; soaring greenhouse gas emissions; pollution; degradation of eco-tourism in Limpopo; and frustrating the access rights of communities who won a land claim around the project site.

Several civil society groups are also contesting the legality of the project in three separate cases currently before courts in Pretoria and Polokwane.

Nevertheless, in March 2022, the South African office of the UNDP – the UN’s largest development aid agency, with offices in more than 170 countries – lent its official backing to the MMSEZ plan when it signed a non-binding memorandum of agreement (MOU). This promised technical backing and expertise along with other unspecified forms of support to foreign investors.

The wording of the MOU indicated that this was the foundation for a more formal partnership in the future, and internal correspondence suggested that the country office “was also considering how the funding for the action plan would be raised”.

Objections lodged

From left: Dr Ayodele Odusola, the UNDP’s former representative in South Africa, and Lehlogonolo Masoga, MMSEZ chief executive, sign the MOU in March 2022. (Photo: UNDP/MMSEZ press announcement)

The agreement was signed by the UNDP’s South Africa representative Dr Ayodele Odusola, who was re-deployed to the agency’s Harare office four months ago.

Now, following a formal objection lodged more than a year ago by social and environmental groups Living Limpopo and Earthlife Africa, the UNDP’s endorsement is set to be cancelled.

In a 29-page final draft investigation report, which came to light at the weekend, the SECU formally recommended that UNDP pull the plug on supporting such a “high risk” project as no due diligence was conducted, as required by UNDP policy.

“The fact that the signing of the MOU resulted in UNDP being publicly identified as a partner means that the mere existence of the signed MOU had significance for (the Limpopo Economic Development Agency). This in turn exposed UNDP to whatever reputational risks may arise from being associated with a company, whose project (pursuant to the applicable policies) the UNDP considers to be high risk.”

Hailing the SECU decision as a significant victory, Living Limpopo spokesperson Lauren Liebenberg said: “The MMSEZ is an environmental and economic Chernobyl, and we are gratified that our objections to its endorsement by the UNDP in this manner has been upheld. We look forward to entering into a constructive dialogue with the UNDP on the alternative, nature-based economic development plan Vhembe Biosphere Reserve for which Living Limpopo advocates.”

Robert Krause, a researcher at the Centre for Applied Legal Studies, suggested that the Limpopo heavy industry cluster also posed “a grave threat” to communities’ livelihoods and their way of life, water security, biodiversity and the prevention of runaway climate change.

“The UNDP and all decision-makers now have a new opportunity to meaningfully consult communities and other stakeholders on how to chart a people-centred development path that brings much-needed broad-based prosperity while conserving this irreplaceable landscape.”

A spokesperson for the UNDP’s Pretoria office confirmed that the SECU report was received on February 21, stating: “We are reviewing the interim findings; we look forward to the final report and recommendations.

“UNDP’s Social and Environmental Standards (SES) are a mandatory requirement for all parts of the organisation – in all programmes and projects – as part of UNDP’s quality assurance and risk management process. The Social and Environmental Compliance Unit (SECU) was established to ensure accountability to individuals and communities we work with. It is important that their voices are heard, and gives UNDP the opportunity to respond to the issues that they raised.”

Senior MMSEZ officials, however, have not responded to requests for comment sent on Friday morning, February 23.

‘Using’ the UNDP

An artist’s impression of part of the proposed MMSEZ project in Limpopo. (Photo: MMSEZ website)

The SECU report notes that the Limpopo government agency sought a written agreement with UNDP “precisely because it believed that engaging with the [UNDP] would help it deal with the challenges that it faced in its relations with outside stakeholders, who were concerned about the potential adverse social and environmental impacts of the project”.

In other words, the Limpopo agency appeared to be “using” UNDP to help it resolve problems with local stakeholders opposed to the project, by listing the UN aid agency as a strategic partner.

“Given that one of UNDP’s strongest assets is its good name and high reputation, the potential costs of exposing itself to reputational risk without proper due diligence are considerable,” the SECU report warns.

SECU stressed that it had not investigated the merits or specific risks of the MMSEZ project. Instead, the eight-month investigation focused solely on whether its South African office had complied with all the applicable UNDP policies and procedures.

It notes that the UNDP has two distinctly different templates for entering into MOUs – one for the private sector and one for governments/state-owned entities. In the case of MMSEZ, the UN country office erroneously signed a less onerous government template.

“The private sector template has provisions dealing with publicity, the use of the UNDP emblem and reputational risk. Had the country office used the private sector template it would have been prompted to seek representations from [LEDA] to assure itself of certain facts before entering into the MOU.

Carbon emissions

“The potential “vast scale use of coal” was one of the many risks flagged by Living Limpopo and Earthlife Africa, who argued that the MMSEZ project was expected to generate nearly 1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions over the lifetime of the project – and would therefore consume between 10% to 24% of the country’s carbon emission budget.

This was disputed by the UNDP’s Odusola, who said in July 2022 that MMSEZ had provided assurances that it had “jettisoned” plans for a coal-fired power plant in favour of a renewable energy project.

The SECU report further notes that project documents make it clear that the Limpopo heavy industry plan would be very water-intensive, mainly drawing from the Limpopo River.

“The complainants are concerned that this water will go to the project at the expense of the resiliency of the Limpopo River basin system and all those who depend on it. In other words, they are worried that the project will take the water that they currently depend on for its own purposes, thereby threatening their ability to access enough water for their farms, households and other needs.”

A further risk factor involved potential human rights violations against the Mulambwane community, who were forcibly evicted from their land during the apartheid era.

“Following the advent of democracy in South Africa, the Mulambwane filed a land claim seeking to regain access to their land. Their claim was successful, and they were authorised to take possession of their land again. However, since their legal victory, they have not been able to reclaim their land. This land has now become part of the land that the state has designated for the MMSEZ, further complicating the resolution of this issue.”

As a result, the compliance unit now recommends that UNDP’s South African office should “withdraw” from the MOU.

It said that if LEDA wished to continue its relationship with the UNDP, the parties would need to prepare a new MOU using the correct private sector template, and the UNDP would also need to complete the necessary due diligence “including the necessary consultations with the appropriate offices in the UNDP hierarchy, before signing a new MOU”. DM

Illustrative image: The United Nations Development Programme signed a Memorandum of Understanding with South African officials in March 2022 to support the Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone in Limpopo. A UNDP watchdog has now advised the body to withdraw its backing for the heavy industry plan. (Photos: Supplied and UNDP/MMSEZ press announcement)

By Tony Carnie | 25 Feb 2024

A United Nations internal watchdog unit has advised its biggest development aid agency to scrap an agreement backing the development of a R165-billion heavy industry zone in Limpopo. Citing the risk of significant reputational harm to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the agency’s New York-based Social and Environmental Compliance Unit (SECU) has recommended the immediate cancellation of an agreement signed two years ago to support the controversial Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone (MMSEZ).

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The project, driven by the state-owned Limpopo Economic Development Agency (LEDA), was initially touted as a R165-billion scheme supported by a consortium of Chinese investors. It would entail building a major 8,000ha heavy industry hub roughly halfway between the towns of Musina and Makhado next to the coal- and mineral-rich Soutpansberg region.

A map showing the boundaries of the proposed MMSEZ. (Photo: MMSEZ environmental impact report)

It would feature up to 20 new industrial projects clustered together in a single tax- and duty-free zone. This would include a new iron and steel plant, a ferrochrome plant, a chrome plating plant; an agro-chemical and petrochemical manufacturing plant; mineral beneficiation; a new Smart City and a logistics cluster projected to attract foreign direct investment. It would apparently create between 21,000 to 53,000 jobs.

However, the project has drawn strong criticism from several quarters for a variety of reasons – including concerns about massive water demands from heavy industry in a water-scarce region; soaring greenhouse gas emissions; pollution; degradation of eco-tourism in Limpopo; and frustrating the access rights of communities who won a land claim around the project site.

Several civil society groups are also contesting the legality of the project in three separate cases currently before courts in Pretoria and Polokwane.

Nevertheless, in March 2022, the South African office of the UNDP – the UN’s largest development aid agency, with offices in more than 170 countries – lent its official backing to the MMSEZ plan when it signed a non-binding memorandum of agreement (MOU). This promised technical backing and expertise along with other unspecified forms of support to foreign investors.

The wording of the MOU indicated that this was the foundation for a more formal partnership in the future, and internal correspondence suggested that the country office “was also considering how the funding for the action plan would be raised”.

Objections lodged

From left: Dr Ayodele Odusola, the UNDP’s former representative in South Africa, and Lehlogonolo Masoga, MMSEZ chief executive, sign the MOU in March 2022. (Photo: UNDP/MMSEZ press announcement)

The agreement was signed by the UNDP’s South Africa representative Dr Ayodele Odusola, who was re-deployed to the agency’s Harare office four months ago.

Now, following a formal objection lodged more than a year ago by social and environmental groups Living Limpopo and Earthlife Africa, the UNDP’s endorsement is set to be cancelled.

In a 29-page final draft investigation report, which came to light at the weekend, the SECU formally recommended that UNDP pull the plug on supporting such a “high risk” project as no due diligence was conducted, as required by UNDP policy.

“The fact that the signing of the MOU resulted in UNDP being publicly identified as a partner means that the mere existence of the signed MOU had significance for (the Limpopo Economic Development Agency). This in turn exposed UNDP to whatever reputational risks may arise from being associated with a company, whose project (pursuant to the applicable policies) the UNDP considers to be high risk.”

Hailing the SECU decision as a significant victory, Living Limpopo spokesperson Lauren Liebenberg said: “The MMSEZ is an environmental and economic Chernobyl, and we are gratified that our objections to its endorsement by the UNDP in this manner has been upheld. We look forward to entering into a constructive dialogue with the UNDP on the alternative, nature-based economic development plan Vhembe Biosphere Reserve for which Living Limpopo advocates.”

Robert Krause, a researcher at the Centre for Applied Legal Studies, suggested that the Limpopo heavy industry cluster also posed “a grave threat” to communities’ livelihoods and their way of life, water security, biodiversity and the prevention of runaway climate change.

“The UNDP and all decision-makers now have a new opportunity to meaningfully consult communities and other stakeholders on how to chart a people-centred development path that brings much-needed broad-based prosperity while conserving this irreplaceable landscape.”

A spokesperson for the UNDP’s Pretoria office confirmed that the SECU report was received on February 21, stating: “We are reviewing the interim findings; we look forward to the final report and recommendations.

“UNDP’s Social and Environmental Standards (SES) are a mandatory requirement for all parts of the organisation – in all programmes and projects – as part of UNDP’s quality assurance and risk management process. The Social and Environmental Compliance Unit (SECU) was established to ensure accountability to individuals and communities we work with. It is important that their voices are heard, and gives UNDP the opportunity to respond to the issues that they raised.”

Senior MMSEZ officials, however, have not responded to requests for comment sent on Friday morning, February 23.

‘Using’ the UNDP

An artist’s impression of part of the proposed MMSEZ project in Limpopo. (Photo: MMSEZ website)

The SECU report notes that the Limpopo government agency sought a written agreement with UNDP “precisely because it believed that engaging with the [UNDP] would help it deal with the challenges that it faced in its relations with outside stakeholders, who were concerned about the potential adverse social and environmental impacts of the project”.

In other words, the Limpopo agency appeared to be “using” UNDP to help it resolve problems with local stakeholders opposed to the project, by listing the UN aid agency as a strategic partner.

“Given that one of UNDP’s strongest assets is its good name and high reputation, the potential costs of exposing itself to reputational risk without proper due diligence are considerable,” the SECU report warns.

SECU stressed that it had not investigated the merits or specific risks of the MMSEZ project. Instead, the eight-month investigation focused solely on whether its South African office had complied with all the applicable UNDP policies and procedures.

It notes that the UNDP has two distinctly different templates for entering into MOUs – one for the private sector and one for governments/state-owned entities. In the case of MMSEZ, the UN country office erroneously signed a less onerous government template.

“The private sector template has provisions dealing with publicity, the use of the UNDP emblem and reputational risk. Had the country office used the private sector template it would have been prompted to seek representations from [LEDA] to assure itself of certain facts before entering into the MOU.

Carbon emissions

“The potential “vast scale use of coal” was one of the many risks flagged by Living Limpopo and Earthlife Africa, who argued that the MMSEZ project was expected to generate nearly 1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions over the lifetime of the project – and would therefore consume between 10% to 24% of the country’s carbon emission budget.

This was disputed by the UNDP’s Odusola, who said in July 2022 that MMSEZ had provided assurances that it had “jettisoned” plans for a coal-fired power plant in favour of a renewable energy project.

Code: Select all

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-11-19-how-the-musina-makhado-sez-will-parch-the-people-of-zimbabwe/“The complainants are concerned that this water will go to the project at the expense of the resiliency of the Limpopo River basin system and all those who depend on it. In other words, they are worried that the project will take the water that they currently depend on for its own purposes, thereby threatening their ability to access enough water for their farms, households and other needs.”

A further risk factor involved potential human rights violations against the Mulambwane community, who were forcibly evicted from their land during the apartheid era.

“Following the advent of democracy in South Africa, the Mulambwane filed a land claim seeking to regain access to their land. Their claim was successful, and they were authorised to take possession of their land again. However, since their legal victory, they have not been able to reclaim their land. This land has now become part of the land that the state has designated for the MMSEZ, further complicating the resolution of this issue.”

As a result, the compliance unit now recommends that UNDP’s South African office should “withdraw” from the MOU.

It said that if LEDA wished to continue its relationship with the UNDP, the parties would need to prepare a new MOU using the correct private sector template, and the UNDP would also need to complete the necessary due diligence “including the necessary consultations with the appropriate offices in the UNDP hierarchy, before signing a new MOU”. DM

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge