Whole Southern Ocean ecosystems, and individual marine species — from krill to whales — are impacted by vessels that fish, conduct seismic research, transport tourists and more. (Graphic: Righard Kapp)

By Tiara Walters | 11 Dec 2022

For decades, state officials, tourists, scientists and fisheries have noisily pushed into a sound-sensitive, ice-bound wilderness where some of Earth’s most endangered and iconic animals seek refuge. As the world’s polar vessels descend on the Southern Ocean for yet another summer of scientific research, fishing and sightseeing, Antarctica’s protected species may again have to pay the ultimate price.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

In Part One of this investigation, Our Burning Planet reveals the disturbing impacts of underwater noise in a globally critical — but existentially threatened — ocean refuge. In our upcoming sequel, we expose the years-long failure by Antarctic states to stop the ongoing suffering that may be experienced by an array of vulnerable species.

Wrapping around the bottom 10% of the globe, Antarctica and its Southern Ocean are widely hailed as Earth’s only natural reserve devoted to peace and science. Five times bigger than Australia, it is a hostile, achingly beautiful place that also embraces the global climate engine within its Circumpolar Current.

Yet, for nearly 25 years, Antarctic state officials charged with protecting this reserve have been aware of the human noise war raging below the surface of the Southern Ocean. While these actors have yet to propose “breakthrough” action after secretive, closed-door talks — sometimes failing to discuss the problem for years at a time — unique marine species such as emperor penguins, blue whales, elephant seals, colossal squid and even seafloor creatures may suffer substantial stress and harassment when thousands of humans sail into their home every summer.

Now a pioneering review study, which has not been previously reported, details the searing blows of Southern Ocean noise pollution — and reveals why another summer of misery may await the species of this uniquely rich wilderness.

Led by Curtin University in Perth, the peer-assessed review study is the first of its kind, highlighting limited findings by the small number of bioacoustics experts to have probed noise across species in the faraway Southern Ocean.

This whodunit, therefore, is still unfolding, highlighting the urgent need for more research. Yet it reflects a growing body of evidence of sensory distress in the Southern Ocean — which may be as severe as hearing loss, injury and death.

This Our Burning Planet investigation also helps unravel a chilling truth: just how deadly “peace” in Antarctica can be.

Natural orchestra — populations under threat

Sound is how the inky ocean sees.

Guided by natural music coursing beneath the waves, marine species use their hearing more than any other sense to find mates, feed, navigate, avoid hazards, and more.

Yet, the rogue’s gallery of human noise that seems to be infecting the Southern Ocean is likely to cause “acute to chronic impacts” in species ranging from “tiny zooplankton to enormous whales”, says the review study, which is published in a policy-information portal managed by the influential Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR). These disturbing effects can disrupt feeding, reduce prey and plague reproduction.

Indeed, when the sun creeps into the Antarctic’s dark waters late August every year, legions of government personnel, scientists and tourists soon follow, chasing the brief window of warmer summer temperatures between October and March. And when those crowds take off, they haul with them a cacophony of vessels and scientific equipment that could be overwhelming, and possibly killing, the Southern Ocean’s natural orchestra.

Damage across sound frequencies may be felt most severely by Antarctica’s 20-odd marine mammals — including top predators such as killer whales and leopard seals — thought to have evolved some of the highest auditory sensitivity among ocean life.

Whole populations could be disturbed, specifically in areas that are important to them.

“Chronic exposure” even to lower types of noise — which rips through water almost five times faster than air — could lead to permanent hearing loss, say the review authors.

Representing universities and agencies in Australia and the US, the authors have also relied on international studies from a range of institutions about similar species that do not occur in the Antarctic.

Adélie penguins waddle across sea ice in East Antarctica. (Photo: Tiara Walters)

Bucket-list bonanza: meet the noisemakers

Even without people, natural Antarctica can be an awesomely violent theatre of cracking icesheets, hollering winds and glaciers thundering into the Southern Ocean.

But in the 2022/23 summer, 100,000-plus sightseers are likely to descend on the region for the first time ever in a single season. This would add another raucous dimension to a hydra of existing stressors: as shown by new discoveries on microplastics in Antarctic air, sediment and ice; thermal stress in heating waters; and alien competitors.

At least, as Our Burning Planet has reported, this flood of tourists is a stark departure from the fewer than 7,000 cruise passengers who trickled to those wild shores 30 years ago.

As though the pandemic pause never was, most ship tourists will rumble towards the accessible but rapidly warming Antarctic Peninsula off South America. This is where endangered species such as the emperor penguin — whose responses to noise have yet to be understood — also like to be.

“There are no international shipping routes through the Southern Ocean,” but traffic has “steadily increased in recent years”, adds the review study.

Noise may infiltrate the region through, among others, aircraft and a variety of shipping — especially fishing vessels; and big, bulky ships that sail under the national flags of those heavyweight Antarctic states.

That is because research and resupply ships from the 29 decision-maker states signed up to the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) — the wider suite of agreements that rules the region — amount to about 50 in-service vessels.

And during 2021 and 2022, about 45 vessels were registered under the ATS’s fisheries body — clunkily known as the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. (This is shortened to CCAMLR, but pronounced “Camelahr” — as the relative few in the know would have it.)

Apart from plying the Ross Sea, East Antarctica and subantarctic waters, much of the fishing trade thrums around the top of the Antarctic Peninsula — also emperor territory.

And such numbers do not even account for fishing cargo and fuel exchanges that can be particularly secretive — even more so than illegal missions, says Dr Ricardo Roura, governance advisor to the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition. The only non-profit environmental group on the planet afforded observer status at ATS meetings, this coalition was not involved in the review study.

The biggest share of traffic around the Antarctic Peninsula, however, appears to come from the roughly 70-plus passenger vessels registered under the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO). The top tourism organisation for the region, many of its members ferry hundreds or thousands of passengers per voyage, but unreported tour operators not registered with IAATO, or other types of vessels sailing under non-ATS states, may also add to the Southern Ocean’s mêlée of noise.

All this traffic becomes expressly awkward when considering that it is the decision-maker states that have sworn to uphold the Madrid Protocol, the ATS’s celebrated environmental constitution; while other international conventions and ATS laws outline conservation mandates for seals, seabirds and whales.

Proclaimed in 1998 in the Spanish capital to international fanfare, the protocol promises to ban mining and limit other stressors likely to be terrible for sensitive Antarctic wilderness — including discharging firearms and explosives near animals.

And, of course, the protocol is meant to control marauding sightseers — who may hardly be aware of just how noisy, and damaging, their bucket lists can be.

As it is, at the ATS’s mid-year annual meeting in Berlin, officials from Ecuador, Spain and the US had to remind fellow diplomats of this remarkable fact: member states had yet to establish “permanent” programmes to monitor how tourists were altering this globally critical polar ark.

Though some monitoring attempts have lately launched, these officials noted: “There has been no development of systematic, permanent — long-term — monitoring programmes focusing on the environmental impacts of tourism in the Antarctic.”

In an emailed response to Our Burning Planet’s questions on the potential noise impacts of tourism, IAATO pointed out its operators “have supported long-term monitoring projects for decades”, such as “Happywhale” and “Penguin Watch”.

“Operators support water sampling, phytoplankton monitoring, carry trained marine mammal observers or researchers and more,” says Hayley Collings, IAATO communications director. Apart from gathering climate data, the association’s members “operate within the parameters of the ATS” and other international laws.

“Parameters include a necessity by the parties to assess all human activity in Antarctica, including tourism, for their impact on the environment before being authorised to proceed,” she says.

A blank cheque for science

As the established narrative holds, the 1959 Antarctic Treaty is a heartwarming story about a bone-chilling place.

Signed during the Cold War by just 12 states including Russia, South Africa, the UK and the US, the treaty’s constitution forms the ATS bedrock, and claims to preserve this continent and ocean region “exclusively for peaceful purposes”. The founding document bans nuclear tests, military activities and owning land, while promoting tourism instead. And, provided this does no harm, the treaty gives a blank cheque to scientific investigation: whether exploring space weather or the secret life of the seabed.

@PeterTFretwell

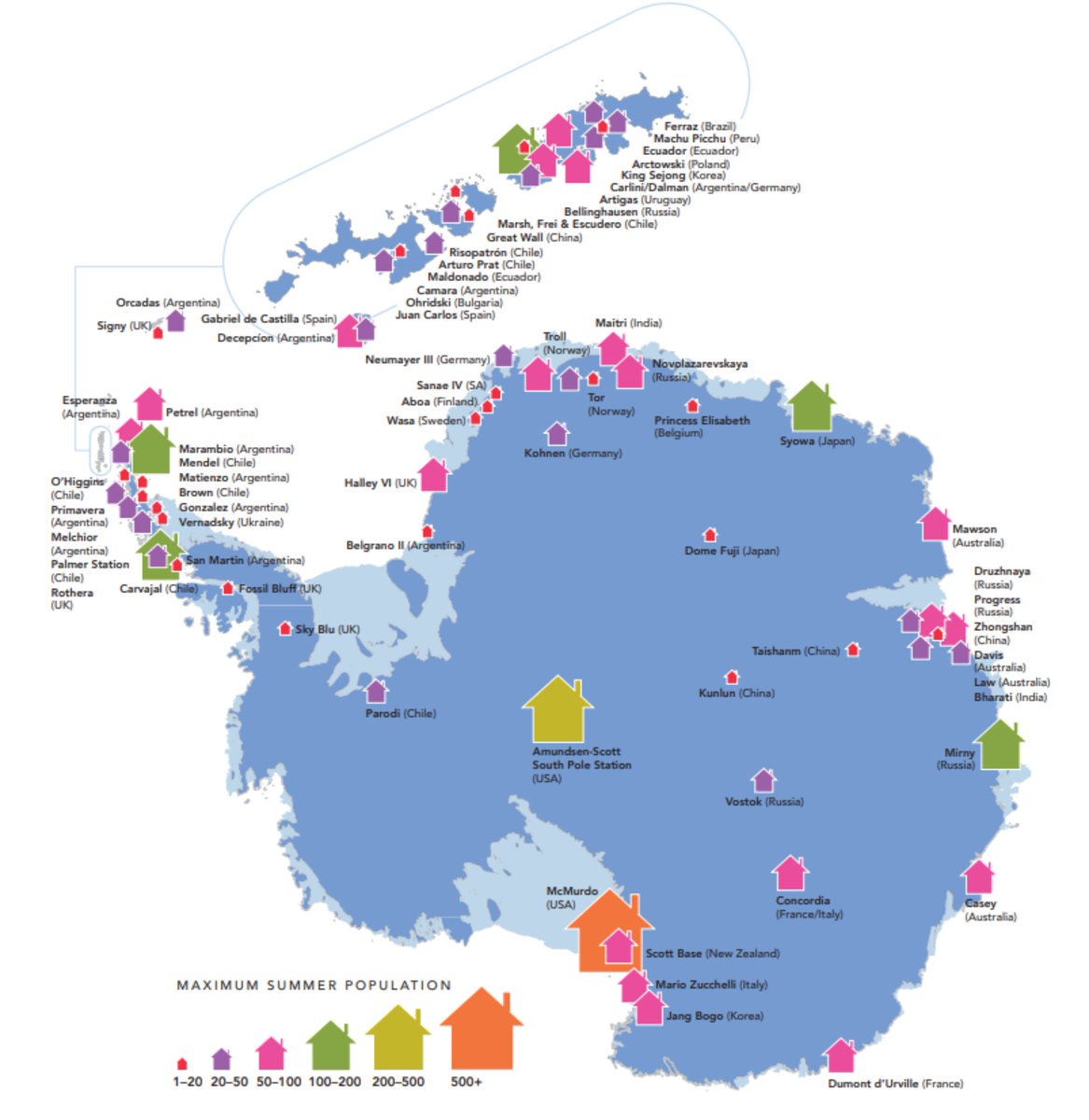

#30DayMapChallenge population data: Bonus map - Antarctic population of research stations from Antarctic Atlas.

Produced for his 30-day map challenge shared on Twitter, a recent indication of Antarctic research stations by the British Antarctic Survey cartographer Peter Fretwell.

But behind this concept of peace and science designed by an exclusive club of world powers, there are colder, harder-edged warnings.

Most of the thousands of scientists and support staff who sail to continental Antarctica every summer smash into the Southern Ocean on ice-cutting hulls.

Their engines boom. Their machinery rumbles. Their propellers clatter and hiss from cavitating, collapsing bubbles.

And some research vessels have seismic airguns that blast out air at up to 260 underwater decibels. This noise slices kilometres into the seabed and shoots back up into vessel hydrophones, which feed the data into machines that make maps of the Earth’s contents. (The blasts are about 17 orders of magnitude louder than natural ambient underwater noise of about 90 decibels — and 10 million times louder than a cargo ship at about 190 decibels.)

And not all scientists sail south to fret about the future of the Southern Ocean, which regulates Earth’s climate but accounts for 50% of global ocean warming since 2005.

A recent series of Our Burning Planet investigations has shown that a Russian vessel outfitted with airguns has not stopped firing shots throughout the Southern Ocean for oil and gas — these activities have forged ahead via Cape Town port ever since the Madrid Protocol and its mining ban became law in 1998.

Almost each annual research season since then, Russian airguns have thundered through 4.5 million km2 of Earth’s last unmined frontier, blasting every 10 seconds. But much in the way Japan has sought to portray its suspended Antarctic whale hunts as research, Rosgeo, the Kremlin’s state explorer, has repeatedly told us its inventory of Antarctic fossil fuels was innocent science.

Russia’s Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute (AARI) and the Committee for Environmental Protection (CEP) — the ATS’s conservation advisor of 42 member states — did not respond to questions on whether Russia had updated its 2001 Antarctic environmental impact assessment (EIA).

Describing noise impacts from Russian ship-based surveys as “less than minor or transitory”, while also praising the Antarctic’s hydrocarbon potential, the assessment exercise concludes that these activities “can be carried out without additional EIA procedures”.

Rosgeo’s Antarctic geology expedition, despite widespread war sanctions, notes it is still licensed by the UN’s seabed authority to survey the central Atlantic for polymetallic sulphides.

The vast extent of Russian oil and gas seismic surveys in Earth’s last unmined frontier since Antarctica’s 1998 mining ban entered into force. (Graphic: Righard Kapp)

Airguns: shooting for the moon

If there is one aspect of Southern Ocean research that cannot be denied, it is this: certain Antarctic marine scientists — from specialised geologists to biologists — love their bioacoustic tools.

Revolutionising seabed insights, seismic cruises have decoded the secrets of the Earth’s crust and drawn sediment cores to puzzle together crucial histories for UN climate reports. Emitting piercing pings of up to 245 underwater decibels, sonar-based echosounders scan for biodiversity and chart dangerous waters at multiple frequencies.

Defending ATS-approved seismic cruises, a 2013 German paper in the journal Antarctic Science claims they had not taken place each summer in the three decades to 2011. Besides, they “usually” relied on 2D systems that used fewer airguns than Big Oil’s rowdier 3D arrays, and their “acoustic impact” was “at least” about 150 times lower.

Indeed, Antarctic airguns and vessels are outnumbered by traffic in other parts of the ocean. But that does not mean their impact is insignificant, says Russell Leaper, a whale and underwater acoustics specialist with the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW). Leaper has also co-authored a leading paper about noise and Southern Ocean marine mammals, which is cited by the new review study.

“Although the Southern Ocean is subject to less human activity than elsewhere, there are a number of factors that may make it very vulnerable to underwater noise,” Leaper warns.

Many species are known to be susceptible to sound, he adds, “including a large proportion of the world’s baleen whales, which are particularly sensitive to low frequencies”.

Seismic surveys are especially concerning, he notes, “because they often occur in areas that are also important to whales”. General shipping noise is also a worry “in areas where expedition ships are going, because they are important to wildlife”.

For their part, echosounders “are often running continuously on research vessels”.

And, despite the German paper’s claims that academic seismic cruises are relative minnows, there is no escaping this elephant seal in the room: these very expeditions have raked in breathtaking distances over at least 35 years.

During this time, that paper admits, 15 member states had amassed seismic data with a collective profile length of 363,801km in total.

That would be at least 501km further than airguns banging several times a minute to the supermoon, which is just about 363,300km or so from Earth in its closest orbital approach.

“All seismic surveys are dedicated to academic research,” the paper insists, citing nearly 130 surveys by member states. But leading up to the 1998 mining ban, most ATS founding signatories, in fact, had been associated with mineral resource prospecting — a mining activity today outlawed in Antarctica, experts argue. These founding signatories included Japan, Norway, apartheid South Africa, the US and the Soviet Union.

The paper says it did not have the capacity to quantify the impact of human noise on marine life — but credits Russia with churning out more than 100,000km of the surveys.

The Russian surveys are followed by at least 60,000km in seismic research from Germany, and contributions from Japan, Italy, Australia and the US, among others.

The German seismic icebreaker Polarstern in Cape Town port, shortly before her October departure for Antarctica’s Southern Ocean. In 2020, on the other side of the world at the North Pole, this icebreaker’s €140-million expedition also marked the world’s single-biggest Arctic climate research project to date. (Video: Xabiso Mkhabela)

South Africa’s current ice-strengthened research vessel, the SA Agulhas II, has no airguns. Instead, she is known for her work in conservation and heritage expeditions. This year, missions that have upended our understanding of Antarctic microplastics; and found Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance ship off West Antarctica, had chartered the South African vessel specifically for that work.

In the Endurance expedition’s EIA, however, the authors left a telling note in a section sub-headed “Noise disturbance to Antarctic fauna and flora”.

Though noises associated with the fêted expedition were deemed minor, it was “general” and “underestimated” human behaviours in the region that were flagged by the authors.

“In general, disturbance effects on Antarctic wildlife appear to have been underestimated,” the consultants observe. This suggests “a more precautionary approach to activities in the vicinity of wildlife is required”.

Hertz so bad: ‘Impacting many sensitive species’

Of the broad soundtrack they spit out when pulsing through the ocean, airguns’ low frequencies — less than 1000 Hertz — are not only thought to pack the most painful punch, they also overlap with sounds made by many marine mammals.

Whale song may try to fight the invaders — but these anthems of the deep die with a whimper when the blasts drown out, or “mask”, low-frequency conversations between the mammals, the review study cautions.

“In extreme cases,” it says, “intense noise sources such as large seismic arrays or underwater explosions can cause immediate injury or even mortality, especially to smaller planktonic animals.”

The review study is also concerned that ships and airguns have stressed out Antarctic baleens. Think humpback and fin whales — and the latter is a recovering, but still-threatened, species. Critically endangered Antarctic blue whales are almost certainly disturbed by noise.

“There is no question in my mind these seismic airgun surveys — regardless of use — cause considerable habitat degradation in the Antarctic, impacting many sensitive species from krill and fish to whales,” Dr Lindy Weilgart, a world authority in underwater acoustics, told us.

A Canada-based marine biologist with Dalhousie University and the non-profit group OceanCare, Weilgart was not involved in these studies.

But as a bioacoustics post-doctoral fellow at Cornell University in 1994, Weilgart sparked a firestorm when she warned about the consequences of the storied physical oceanographer and geophysicist Walter Munk testing warming waters by blasting noise across the Pacific Ocean.

Exposed in the Los Angeles Times, the climate experiment — largely backed by the US military to the tune of $35-million — would ultimately coil its planet-sized hand right around the globe in the decade to 2006. Munk fired low frequencies from the Southern Ocean to South Africa, from Bermuda to Japan, and beyond, earning him renown for pioneering sound as an ocean thermometer.

But Weilgart’s early warnings also ensured his work — greenlit after some concessions — would raise enduring questions within the public psyche about noise pollution. (After World War II, Munk’s research had also supported US atomic weapons testing at Bikini atoll in the Pacific, the latter causing widespread radioactive contamination.)

The Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition, the ATS non-profit observers, tabled none other than Weilgart’s warnings to a 2003 annual meeting attended by member states.

Possible impacts, those very states were informed, included miscarriages; injury; disease; vulnerability to predation; changes in appetite; disrupted mother-calf bonds; panic; anxiety and confusion.

In her interview with Our Burning Planet, Weilgart emphasised “there are legitimate academic uses for seismic surveys, where they study plate tectonics of the ocean floor, earthquake potential”, and so on.

Even so, Weilgart urges that today she is “most concerned about impacts to the ecosystem and ecosystem services — which recent studies confirm”.

‘I don’t think they just ignore this’

Professor Christine Erbe, the international review study’s lead author, insists “industry and government are aware of the potential impacts and we find they do want to minimise these”.

“I don’t think they just ignore this,” says the decorated underwater acoustics expert, who has extensive experience doing EIAs for offshore oil and gas. Erbe is also director of Curtin University’s Centre for Marine Science and Technology.

The CEP, conservation advisor to the ATS, did not respond to Our Burning Planet’s requests for comment.

SCAR, the umbrella committee for Antarctic sciences including airgun research, is yet to address Our Burning Planet’s questions on Russian oil and gas seismic surveys, first sent in October 2021. The committee’s secretariat also did not answer our recent questions on researchers’ environmental obligations under the Madrid Protocol — especially scientists using acoustic instruments. But the secretariat did email us SCAR’s 2019 review of some 135 papers — an ambitious attempt trying to understand noise impacts, understudied species, massive data gaps and what might be done about them.

CCAMLR, the ATS fisheries body also charged with the conservation of the Southern Ocean’s “marine living resources”, told us “the issue” of human-caused noise effects on marine life “is complex”.

According to CCAMLR science manager Dr Steve Parker, “the typical focus” is “the effects of seismic surveys and military operations on marine mammals and therefore much less information is available on the effects of sonars used for navigation or fish detection by fishing vessels”.

Parker says permits for fishing and research vessels operating in the Southern Ocean “are managed by individual members”. They are intended “to be consistent with CCAMLR conservation measures and ATS measures. These permits consider the effects of all operations on marine life and can include mitigation requirements as agreed by the members”.

Noise caused by fishing vessels, Parker concedes, “has not been formally raised by members at CCAMLR”. ATS annual meetings and other bodies, such as the International Whaling Commission, would “most likely” table these issues instead, he says.

Parker also cited SCAR’s 2006 noise workshop, which was on CCAMLR’s meeting agenda that year, and reported by the ATS conservation advisor. At that workshop, he says, delegates “suggested the need for a noise map of the Southern Ocean to evaluate the potential for effects of anthropogenic noise”.

Germany, the only member state to have consistently tabled noise concerns at ATS annual meetings for some 25 years, did not respond to our comment requests. The Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI), Germany’s flagship polar research body, declined to respond to our requests, which included questions on how noise mitigation measures are monitored and enforced.

Hours after declining to respond, AWI’s press office issued a public statement marking the seismic icebreaker Polarstern’s greatest scientific achievements over 40 years — from finding the world’s largest icefish colony of some 60 million nests to calculating that warm water was melting Antarctic ice sheets from below.

The statement hastened to add Germany had recently approved tender calls for a new icebreaker — “tentatively” to be commissioned by 2027. Polarstern 2.0 would “also be a paragon of sustainable shipbuilding and the use of regenerative energy in shipping”, it urged.

Stadium speakers ‘in a village hall’

Indeed, Leaper, the IFAW whale specialist, notes “some national research vessels are built to be very quiet. This is generally effective in terms of reducing ship noise.”

“However,” he says, “the motivation for a quiet ship is often to be able to use other sound sources such as seismic or echo sounders. So, research vessels can still have noise impacts even if the ship itself is very quiet.”

Other technologies should have surpassed airguns, he says, which “have stayed the same for many decades, because regulators have never required the development of better technology”.

Poor enforcement of regulations may have other cascading effects.

“Seismic operators design their systems for the most difficult conditions they are likely to face, which means in better conditions they are using far higher levels than they need to.”

Airguns “are not a controllable source”, he stresses. So, they are “a bit like using the sound system from a large stadium for a concert in a village hall”.

But then, irrespective of the source of noise, there is the kicker, adds Weilgart, who in 2021 co-authored the first analysis on how noise from deep-sea mining might harm species.

“My argument has always been that marine life does not care what the survey is used for,” the bioacoustics expert says. “Loud is loud.” OBP/DM

This article has been updated post-publication to include the comment from CCAMLR, the ATS fisheries body, which was received after the deadline.