Bush encroachment in Mahangu National Park, Namibia. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

By Don Pinnock - 08 May 2024

A tree surge doesn’t have the drama of a freak storm surge or a monster hurricane to alert us to climate change, but as airborne carbon builds, trees are on steroids. It’s bad news for grasslands which cover a fifth of the planet – and the creatures they support.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By the end of the century, much of the Serengeti, the Masai Mara, Kruger Park’s open plains, the US prairies, the Asian steppe, Brazil’s Pantanal and the creatures who depend on them could be nothing but a memory.

In their place may be impenetrable scrubland.

The reason is that leafy plants love carbon and our lifestyle is dishing it out in megatons every day.

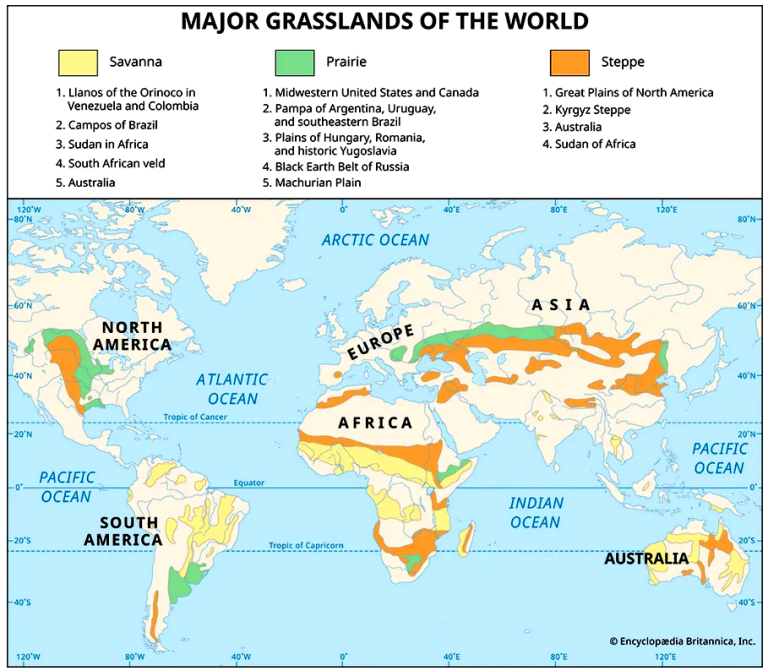

World’s major grasslands. (Graphic: Wiki Commons)

Grasslands, on the other hand, are not so carbon-aggressive and – in the ancient war between trees and grass – the balance has increasingly tipped. That’s bad news for huge areas of the planet being overrun by scrub bush as well as for the plains animals who depend on grass.

This is deeply concerning to the University of Cape Town’s Prof William Bond, who says there’s a looming crisis that governments and even many scientists are unwilling to address. What alarms him is that we’re aiding the march of trees by planting them in an attempt to offset the build-up of CO2.

“Our fetish for trees is biological vandalism,” he says.

“They get planted on grasslands which sequester more carbon below-ground than forests. If grasslands vanish, it could catalyse an avalanche of extinctions.”

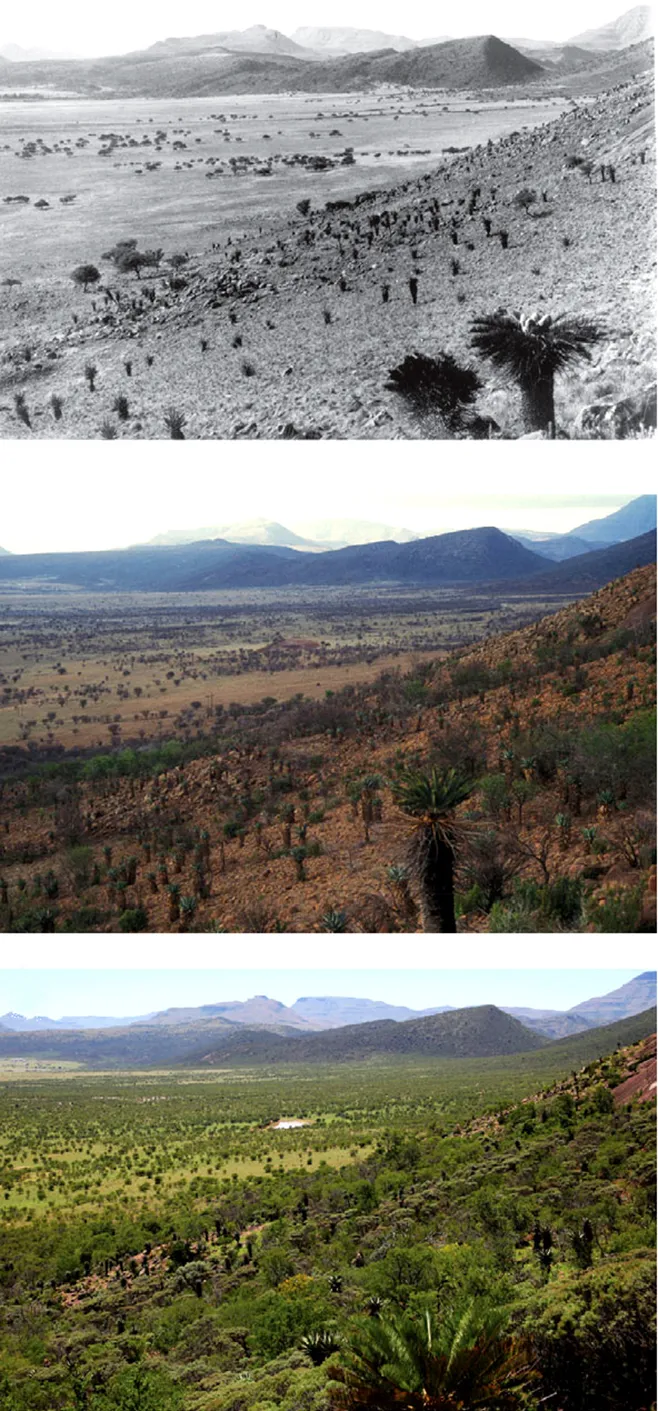

The wild valleys of Warmwaterberg at Sanbona. Woody thickening over the past century near Queenstown, Eastern Cape. Acacia karoo is the most common tree species in this mesic savanna. (Photos: IP Pole Evans, Timm Hoffman and James Puttick reproduced courtesy of rePhotoSA)

Concern has been bouncing around among a number of academic botanists for some time, but with little effect on environmental policy.

Environmental activists aren’t running with it. This might be because, like global warming, the tramp of trees is a complex set of moving parts hard to get to grips with in lay terms. Also, many of the studies are behind costly academic paywalls for accessing publications.

Grass thrives on fire – some trees in certain areas resist it and others succumb to it. Savanna trees are more tolerant of competition with grasses while forest trees block out light and suppress grass which needs plenty of sunlight. In human settlements, trees are cut down for wood.

The forest edge. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

In Africa, elephants and antelope are grassland allies, the former pushing over trees, the latter nibbling new tree shoots, all helping to reduce woody cover. The declining number of elephants across the continent and the suppression of natural fires are flagged as significant causes of bush encroachment.

Leaves love carbon

Here’s the problem. With growing intensity, CO2 is favouring leaves over grass, increasing the ability of trees to retain water, deepening their roots and increasing their ability to resist fire. This has to do with how trees “breathe”.

Leaves are covered with stomata – essentially mouths that open to admit CO2 and, at the same time, exhale water vapour. As CO2 increases, they don’t need to open their stomata as wide. This reduces water loss and retains it for tree use in their roots below the depth where grass can access it.

According to Bond and Stellenbosch researcher Guy Midgley, an increase in water efficiency is likely to be a key mechanism favouring woody plant thickening in semi-arid savannahs, increasing soil moisture supply and favouring tree seedling and subsequent growth in competition with grasses.

In a paper on the uneasy interactions between trees and savanna grass, they say that during the past century, increasing CO2 levels have fuelled changes in savannah tree growth, helping to create “super-seedlings”.

“Relative to a century ago, young trees have faster growth, massive root systems with larger starch reserves and a greatly enhanced capacity for resprouting after injury.”

Because trees have abundant carbon, says Bond, they recover and resprout easily after fires, which are no longer the ally of grasses.

Pantanal in Brazil under threat from scrub invasion. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

In a research paper on 94 studies covering 110 global savanna sites, which appeared in Global Change Biology, its authors found woody encroachment in 84% of them. This intrusion was apparent in the 1970s but has accelerated and is occurring right across the world’s savannas.

Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere have varied greatly over the past 65 million years and resulted in widespread changes in vegetation. It rose to greater than 1,000 parts per million in the Eocene (50 million years ago) and forests spread to their greatest extent.

In the Oligocene, around 25 million years ago, CO2 dipped and grasses thrived. By about eight million years ago, they were a major biome.

During the Pleistocene (from 2.5 million years ago) they expanded and contracted in rhythm with ice ages with lower CO2 in glacial periods.

Boom time

Bond and Midgley suggest that the savannah biome may now be heading for an abrupt decline owing to human impacts on the carbon cycle.

Within the next 100 years, savannah plant species are likely to experience CO2 levels outside their entire evolutionary history.

Old-growth grasslands are unique in their underground structures and biodiversity. They store carbon and reallocate resources above ground after disturbances and drought. Once destroyed, they cannot easily bounce back.

Research in the journal Science warns it’s unlikely that restored grasslands will ever completely recover to resemble old-growth grasslands.

Bush-encroached land at the Waterberg Plateau Park in Otjozondjupa Region, Namibia. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

Agriculture, mining and afforestation destroy their below-ground structure and may require millennia to recover their former species’ richness.

“Once these below-ground structures are gone, we have little understanding of how to reintroduce this component of the vegetation. Tree planting in grasslands and conversion to agriculture are irreversible actions.”

Forest fetish

In the rush to provide nature-based solutions to tackle climate change, tree planting in grasslands has become synonymous with restoration.

The core of global reforestation projects, says Bond, is the misconception that grasslands were once forests and were created and maintained by human-lit fires. In fact, grasslands are fire-dependent and predate humans by millions of years.

“Fire has been a natural part of the Earth’s system for 400 million years… long before people.

“So the whole conception of forest being the natural vegetation of the tropics and grasslands being caused by humans burning trees is nonsense.”

A paper in Science by Catherine Parr, Mariska te Beest and Nicola Stevens warns of the dangers of this misclassification. They say this could cause degradation and warn against greenwashing.

Trees on the march across savanna grassland. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

“We must act to avoid a situation where we cannot see the savanna for the trees and these precious grassy systems are lost irrevocably.”

“The urgency of implementing large-scale tree planting,” says Stevens, “is prompting funding of inadequately assessed projects that will most likely have negligible sequestration benefits and cause potential social and ecological harm.”

This is echoed by another research project reported in Science:

“Much of the emphasis has been on the restoration of forests,” the authors write. “Ironically, this emphasis presents an additional threat to grasslands – careless or poorly planned tree-planting efforts in the name of restoration can establish forests in natural grassland.

“Almost a million square kilometres of Africa’s grassy biomes have been targeted for tree planting by 2030. This practice ignores the value of protecting and restoring grasslands.”

The assumed primacy of forest systems and the drive to sequester carbon to offset climate change are powerful enough ideas to deflect researchers from exploring the diversity of grasslands, says Bond.

Instead, more than a billion dollars has been pledged by governments, the United Nations and non-government organisations to “reforest”.

“Across Africa, a total of 133.6 million hectares have been pledged towards (the tree-planting and seeding project) AFR100 in 35 countries.” Nearly half of that – about the size of France – is in non-forest ecosystems, mainly savannas and grasslands.

Major research organisations working in reforestation seem unaware of the threat to grasslands.

In a 164-page global assessment report on the state of forests by the International Union of Forest Research Organisations released this week on 6 May, there was not a single mention of grasslands or savanna.

“Tree planting is just a sop to the public who have this forest fetish,” says Bond.

“I don’t believe that sequestering carbon is going to make a quick enough difference through nature. The only way to really solve the carbon problem is to shut down fossil fuel use.”

In savannas, most of the carbon is being taken up by grasses and grass roots. When you plant trees, the grasses are suppressed, he says, and that source of carbon sequestering is lost.

“You need to harvest trees and stash away that carbon and grow some more trees and stash away their carbon. So the carbon sequestration people are in it for rapid-growing trees that can soak up a lot of carbon quickly. That means growing eucalyptus and pines.

“I have no problem with well-planned commercial plantations. But to argue that this is going to solve the world’s global warming problems is fraudulent, it’s nonsense. But, of course, there are people who are going to make money out of it.”

How long will grasslands survive?

“I think that the closing over, at least to the point where plains animals can no longer exist, could happen very quickly and it’s moving more rapidly than people realise. And we don’t really know what to do about it.

“I think we’re facing a big war of trees. What we need are more elephants, impala and goats. And to stop using fossil fuels.” DM