THE FEMALE OF THE SPECIES IS DEADLIER THAN THE MALE

Wendy Collinson-Jonker, Programme Manager EWT Wildlife and Transport Programme, wendyc@ewt.org.za

Men have dominated our society and controlled our commerce for most of recorded history. Rudyard Kipling’s poem, written in 1911, implies that women are more dangerous than men, referring to animal species in which the female is more aggressive than the male. A prime example of this is sexual cannibalism, a behaviour in which a female animal kills and consumes the male before, during, or after copulation, common amongst insects. Female dominated societies, such as matriarchal elephant herds and hyaena clans, are also observed in the animal kingdom. Does this make the female more dangerous? Highly unlikely, but it may make her more vulnerable.

Historically, women have commonly been referred to as the “fairer sex”, usually based on their apparent vulnerability and appealing looks, and it seems this stereotype is hard to escape. Women’s beauty is another trait that some believe makes her more deadly, but most of the time, it just makes her more vulnerable. In other species, however, it is often the other way around, with the males much more appealing in appearance than the females. According to Charles Darwin, this was due to two characteristics related to sexual selection: those physical traits that serve as weapons, allowing males to fight for access to females, such as the impressive horns on Kudu bulls, and those ornamental traits that attract the attention of females, such as long tails and bright colours on male birds. As a general rule, birds typically have specific breeding periods (seasonal breeding) so that offspring are born or hatch at an optimal time. The same is true for amphibians and reptiles, also reliant on ambient temperature, precipitation, availability of surface water, and food supply to breed. Mammals, fall more into the category of opportunistic breeders, and are reliant upon other conditions in their environment (aside from time of year), such as prey or forage availability, and can have multiple litters in a year.

Understanding animal behaviour such as breeding habits is critical to understanding the specific threats to our wildlife. Not only does breeding behaviour place wildlife in threatening situations, but these threats, in turn, have an impact not only on the number of live individuals but also on the breeding success of species. A Giant Bullfrog, for example, emerges from hibernation after the first rains and migrates to a different area to breed. Giant Bullfrogs in Gauteng are often required to cross multiple roads to get to their potential mates, and they get killed in their thousands by vehicles, drastically reducing the number of breeding individuals. Of course, this is one of the reasons they are what we call “explosive breeders”, having adapted to emerge and migrate in their thousands, as many simply don’t make it to the other side.

The EWT’s Wildlife and Transport Programme (WTP) has been gathering wildlife road mortality in South Africa since 2013, not only to determine which species are most at risk but also to determine what impact this may have on their populations. One of the ways by which we do this is training route patrollers from three of the toll concessionaire companies (namely, N3 Toll Concession, Bakwena N1/N4 Toll, and TRAC N4) to gather roadkill data, which helps us understand what is happening on these highways.

To date, we have almost 20,000 data points, identifying species most at risk, but most of these do not include the gender of the animal, since it is quite challenging to determine in many species, especially if the animal is very squashed. We know from research undertaken elsewhere in the world that is important to ascertain whether it is males or females being killed on the roads. But why?

We know that male amphibians are very reliant on their vocalisations to not only protect their territory but also to attract a mate. A study in Brazil in 2017 showed that traffic noise affects amphibian calling behaviour, and if a female cannot hear the male call, then breeding is compromised. A collateral effect of this is that the females may spend longer trying to locate males, and her chances of being hit on the road are increased. A study in France showed that more male snakes were killed during their breeding period (especially in species where mate-searching males travel widely), while females in oviparous species are killed during their egg-laying migrations. In North America, male bears chose to avoid roads, while females elect to cross them, but in Australia, more male kangaroos are killed on the roads than females. No matter what the species, roads effectively create “invisible” barriers between wildlife populations, which is something we as humans have experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing creating an invisible barrier between friends and families.

One of the mammal species most impacted on South African roads is the Serval, especially on the N3 highway, with almost 250 killed since 2014. The habitat along the N3 is very favourable for Serval, and we are working closely with N3 to implement some solutions to prevent Serval mortalities. However, information on the sex of the animals being killed is limited, and this information is key to understanding the effects of roadkill on the breeding viability of populations. For example, if more females are being killed, then this will decrease breeding success, while if it is young, dispersing males, this will have less of an impact. To expand on our knowledge and address threats to specific species. The WTP, where possible, will gather information about the sex of a roadkill specimen to understand more about species’ behaviour around roads.

Thank you to the loyal supporters of the Wildlife and Transport Programme, namely Ford Wildlife Foundation, De Beers Group of Companies, N3 Toll Concession, Bakwena N1/N4 Toll and TRAC N4.

EWT Roadkill Project

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67570

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: EWT Roadkill Project

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67570

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: EWT Roadkill Project

BRIDGING THE GAP FOR VERVET MONKEYS

Courtney Maiden, EWT’s Wildlife and Transport Programme student, 64083152@mylifeunisaac.onmicrosoft.com

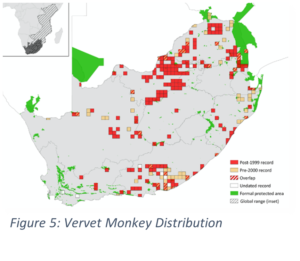

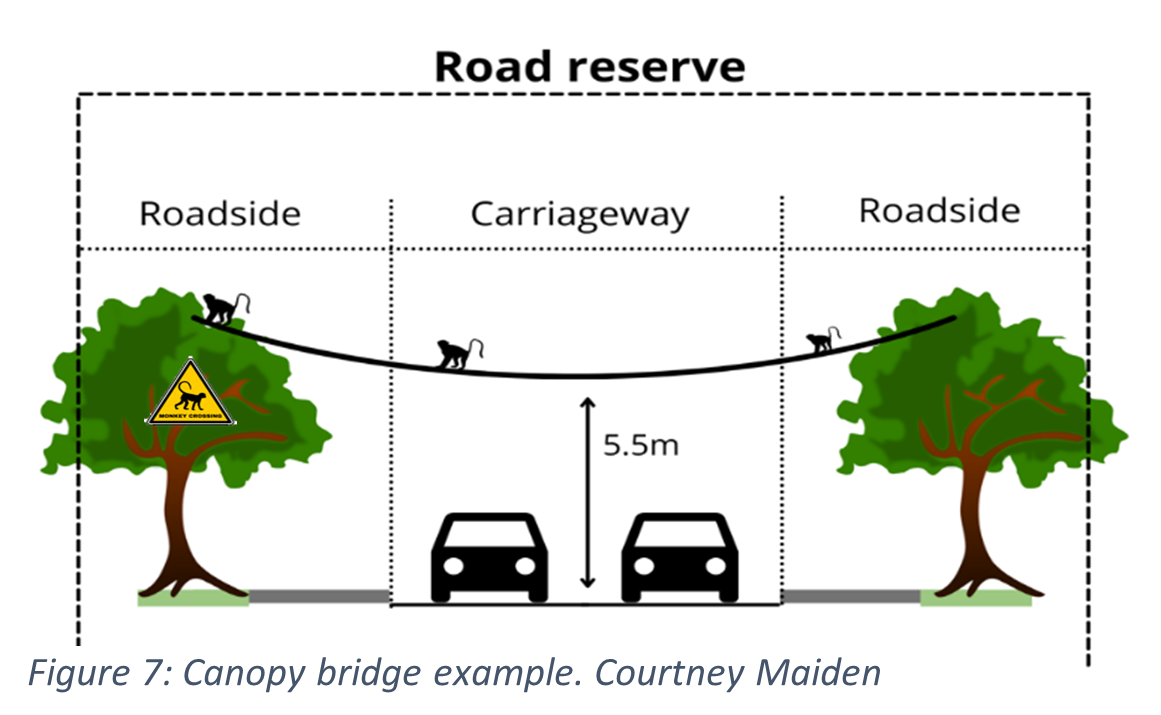

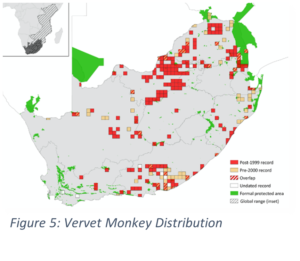

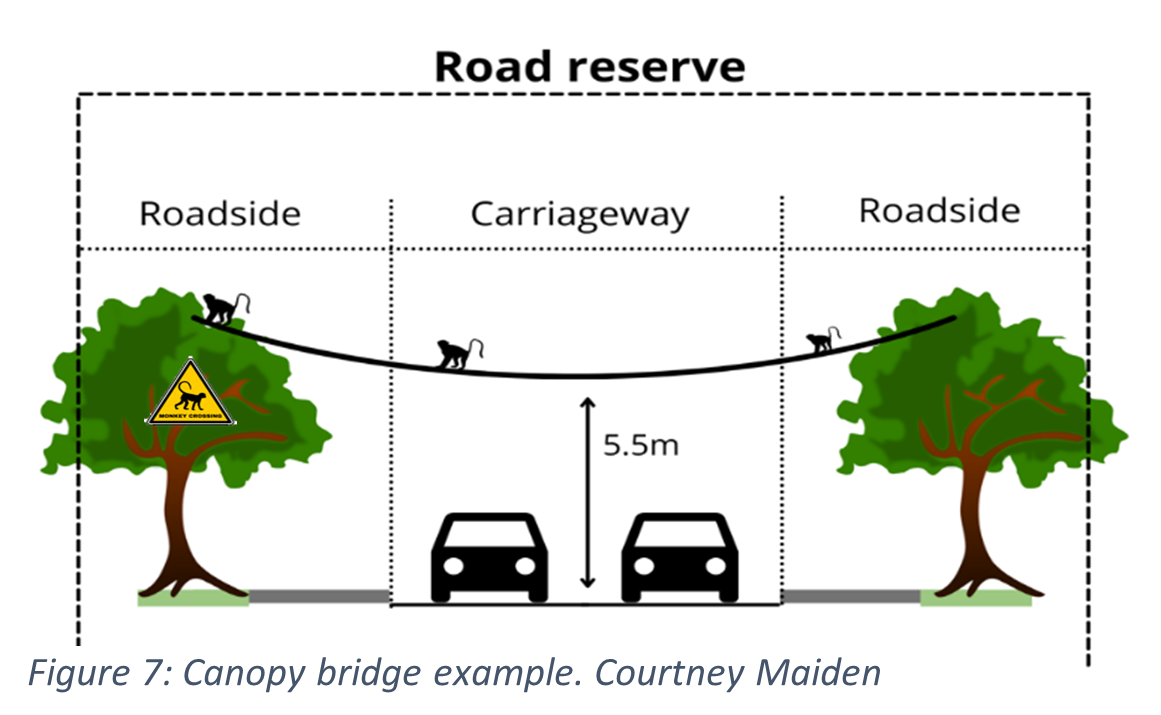

canopy cover from linear infrastructure, such as roads, force arboreal species to come down to the ground and face threats such as wildlife-vehicle collisions. Wildlife crossing structures, such as canopy bridges, have been installed in many countries to reduce the impact of roads and enhance habitat connectivity for tree-dwelling species. The Vervet Monkey (Chlorocebus pygerythrus) is one of the arboreal species subjected to daily vehicle collisions throughout South Africa.

In an attempt to reduce mortalities, EWT student Courtney Maiden is designing and testing Vervet Monkey-specific canopy bridges in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, with an end goal of installing wildlife-friendly bridges in roadkill hotspots across the country. By interrogating proposed designs and methodologies to establish a preferred Vervet Monkey crossing structure design, effective roadkill mitigation processes and species management plans can be established by integrating a simple yet potentially effective design to minimise wildlife-vehicle collisions, encourage habitat connectivity, and ensure the viability of Vervet Monkey populations. This work is being done in collaboration with the University of South Africa and the University of Wisconsin.

Courtney Maiden, EWT’s Wildlife and Transport Programme student, 64083152@mylifeunisaac.onmicrosoft.com

canopy cover from linear infrastructure, such as roads, force arboreal species to come down to the ground and face threats such as wildlife-vehicle collisions. Wildlife crossing structures, such as canopy bridges, have been installed in many countries to reduce the impact of roads and enhance habitat connectivity for tree-dwelling species. The Vervet Monkey (Chlorocebus pygerythrus) is one of the arboreal species subjected to daily vehicle collisions throughout South Africa.

In an attempt to reduce mortalities, EWT student Courtney Maiden is designing and testing Vervet Monkey-specific canopy bridges in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, with an end goal of installing wildlife-friendly bridges in roadkill hotspots across the country. By interrogating proposed designs and methodologies to establish a preferred Vervet Monkey crossing structure design, effective roadkill mitigation processes and species management plans can be established by integrating a simple yet potentially effective design to minimise wildlife-vehicle collisions, encourage habitat connectivity, and ensure the viability of Vervet Monkey populations. This work is being done in collaboration with the University of South Africa and the University of Wisconsin.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67570

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: EWT Roadkill Project

SCIENCE SNIPPETS: THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROAD

Cameron Cormac, PhD Candidate, Centre for Functional Biodiversity, School of Life Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, downs@ukzn.ac.za

For most drivers, it is fairly easy to spot an animal as large as an African Elephant, Cape Buffalo, or rhino on the road. However, despite these animals being highly visible because of their large size, there are still cases of drivers colliding with these large flagship species along roads near or in protected areas. Additionally, with fences being placed around the reserves that South Africa’s most iconic animals call home, aiming to protect both man and animals by keeping animals in and poachers out, the range that these large animals can roam is effectively reduced. But if large animals can be hit by cars and stopped by fences, what effect do roads and fences have on the smaller species that inhabit these protected spaces.

Globally anthropogenic land-use change, including the development of linear infrastructure, impacts species negatively. I am Cameron Cormac, a PhD student from the University of KwaZulu-Natal and working in conjunction with several supervisors, namely: Prof Colleen Downs, Dr Cormac Price (both University of KwaZulu-Natal), Dr Dave Druce, Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, and Wendy Collinson of the Endangered Wildlife Trust. My project aims to answer questions about the effects of linear infrastructure (roads and fences) on vertebrate fauna in Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Park and the Zululand region of KwaZulu-Natal.

There are five questions that my project aims to answer. Firstly, to find out what vertebrate species are killed by vehicles along the sections of the R618 that separates the Hluhluwe and Imfolozi sections of Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Park and the section of the R22 that runs through the northern section of Isamangaliso Wetland Park. Secondly, to determine what vertebrates are dying along fences within Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Park and Phinda Private Game Reserve because the fence impedes them from entering either park. Additionally, to find out what animals are killed along the R22 that runs through multiple rural communities and compare it with the Isimangaliso section of the R22. I am particularly interested in how reptiles and amphibians in this region are affected by the roads and fences. Finally, to determine what measures can be taken to reduce the number of animals that die along the roads and fences that this project is concerned with.

Cameron Cormac recording roadkill

To answer my project’s questions, I conduct surveys in the morning and evening, collecting information on what animals are killed on roads and fences. I also record the environmental conditions when I locate any dead animals, as weather conditions can increase roadkills, and I note whether there are traffic calming or alternative structures for use animals to use to avoid the road. The number of cars that pass by during a set time frame, the number of cars that pass through the road sections in a day, and how far from the edge of the road the animal was are also recorded. This information will provide insights into what drives animals to use the road. Information from social media pages is also being used to obtain additional information about roadkills in the study area. Information on what animals are killed along fences is kindly collected by the rangers and park workers who patrol the reserves. All information is then used to determine what measures can be taken to reduce the mortalities along these man-made structures using computer analyses.

Vervet Monkey roadkill found during road surveys

At least 137 animal deaths have been recorded along the R618 and 103 deaths along the R22 over three months so far, including 77 amphibians, 14 reptiles, 21 birds, and 27 mammals in Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Park and 63 amphibians, 14 reptiles, 17 birds, and 12 mammals in Isamangaliso Wetland Park.

You can also assist in the study. Please send pictures of any animals seen dead or alive on these roads to the Hluhluwe-Imfolozi sightings Facebook group or by using the Endangered Wildlife Trust’s road watch application, which can be found in the Google play store, as this will add to our growing understanding of the threat posed by roads in Hluhluwe-Imfolozi and Isamangaliso Wetland parks. In conclusion, please drive carefully and slow down for all animals crossing the road, not just the large iconic species, and help preserve South Africa’s incredible diversity.

Cameron Cormac, PhD Candidate, Centre for Functional Biodiversity, School of Life Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, downs@ukzn.ac.za

For most drivers, it is fairly easy to spot an animal as large as an African Elephant, Cape Buffalo, or rhino on the road. However, despite these animals being highly visible because of their large size, there are still cases of drivers colliding with these large flagship species along roads near or in protected areas. Additionally, with fences being placed around the reserves that South Africa’s most iconic animals call home, aiming to protect both man and animals by keeping animals in and poachers out, the range that these large animals can roam is effectively reduced. But if large animals can be hit by cars and stopped by fences, what effect do roads and fences have on the smaller species that inhabit these protected spaces.

Globally anthropogenic land-use change, including the development of linear infrastructure, impacts species negatively. I am Cameron Cormac, a PhD student from the University of KwaZulu-Natal and working in conjunction with several supervisors, namely: Prof Colleen Downs, Dr Cormac Price (both University of KwaZulu-Natal), Dr Dave Druce, Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, and Wendy Collinson of the Endangered Wildlife Trust. My project aims to answer questions about the effects of linear infrastructure (roads and fences) on vertebrate fauna in Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Park and the Zululand region of KwaZulu-Natal.

There are five questions that my project aims to answer. Firstly, to find out what vertebrate species are killed by vehicles along the sections of the R618 that separates the Hluhluwe and Imfolozi sections of Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Park and the section of the R22 that runs through the northern section of Isamangaliso Wetland Park. Secondly, to determine what vertebrates are dying along fences within Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Park and Phinda Private Game Reserve because the fence impedes them from entering either park. Additionally, to find out what animals are killed along the R22 that runs through multiple rural communities and compare it with the Isimangaliso section of the R22. I am particularly interested in how reptiles and amphibians in this region are affected by the roads and fences. Finally, to determine what measures can be taken to reduce the number of animals that die along the roads and fences that this project is concerned with.

Cameron Cormac recording roadkill

To answer my project’s questions, I conduct surveys in the morning and evening, collecting information on what animals are killed on roads and fences. I also record the environmental conditions when I locate any dead animals, as weather conditions can increase roadkills, and I note whether there are traffic calming or alternative structures for use animals to use to avoid the road. The number of cars that pass by during a set time frame, the number of cars that pass through the road sections in a day, and how far from the edge of the road the animal was are also recorded. This information will provide insights into what drives animals to use the road. Information from social media pages is also being used to obtain additional information about roadkills in the study area. Information on what animals are killed along fences is kindly collected by the rangers and park workers who patrol the reserves. All information is then used to determine what measures can be taken to reduce the mortalities along these man-made structures using computer analyses.

Vervet Monkey roadkill found during road surveys

At least 137 animal deaths have been recorded along the R618 and 103 deaths along the R22 over three months so far, including 77 amphibians, 14 reptiles, 21 birds, and 27 mammals in Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Park and 63 amphibians, 14 reptiles, 17 birds, and 12 mammals in Isamangaliso Wetland Park.

You can also assist in the study. Please send pictures of any animals seen dead or alive on these roads to the Hluhluwe-Imfolozi sightings Facebook group or by using the Endangered Wildlife Trust’s road watch application, which can be found in the Google play store, as this will add to our growing understanding of the threat posed by roads in Hluhluwe-Imfolozi and Isamangaliso Wetland parks. In conclusion, please drive carefully and slow down for all animals crossing the road, not just the large iconic species, and help preserve South Africa’s incredible diversity.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67570

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: EWT Roadkill Project

How did the monkey cross the road?

Courtney Maiden, Endangered Wildlife Trust MSc Student

Over 750,000 km of roads crisscross South Africa, and the country’s natural habitats and wildlife are gravely threatened by further road development. Furthermore, with the anticipated increase of vehicles on the roads over the coming years, the likelihood of more wildlife-vehicle collisions is worrying. The Vervet Monkey (Chlorocebus pygerythrus) has adapted to thrive in human-altered landscapes. However, this also means they face many risks from humans and their activities. Vervet monkeys face daily challenges living in an urban environment due to increasing habitat loss and fragmentation. The clearing of treed areas for roads and other purposes forces monkeys to the ground, increasing their risk of being hit by vehicles. An important first step in reducing this outcome is the design of safe and cost-effective structures by which animals can safely cross the road.

Over the past two decades, wildlife crossing structures have been installed to facilitate wildlife movement over or under roads and railways to connect habitats and reduce roadkill. These structures are often custom-designed for each site and according to the needs of the targeted species. Yet, less than a handful of studies look at the effectiveness of different measures in reducing wildlife‐vehicle collisions in South Africa. Moreover, systematic assessments on designing safe and cost‐effective crossing structures for wildlife have not been carried out to date in our country, despite their importance in preventing Vervet Monkeys and other animals from becoming roadkill.

In March 2022, Courtney Maiden from the Endangered Wildlife Trust tested three different canopy bridge designs for Vervet Monkeys to identify one standardised design for the benefit of free‐ranging Vervet Monkey troops. The observational experiments took place at the Centre for the Rehabilitation of Wildlife (CROW) in Durban, where the three bridge designs were installed in two Vervet Monkey enclosures. Testing different canopy bridge designs in an ex-situ environment such as CROW allows us to establish design guidelines that can be used for free-ranging Vervet Monkeys in-situ (in their natural habitat). These ex-situ experiments are vital for understanding how Vervet Monkeys behave on different canopy bridge designs and identifying the most suitable bridge design to increase the likelihood of the bridges being used in the wild.

The bridges were made using polypropylene rope and recycled plastic. The design is adaptable to varying installation lengths, heights, and crossing environments. By observing the monkeys directly and using camera trap footage, we found that the ladder bridge was used most often and showed great potential for being the most suitable design.

The positioning of any wildlife crossing structure is equally as important as its design. As the Vervet Monkey is a territorial species with daily foraging paths, installing canopy bridges along preferred movement pathways is vital for maximum benefit. Examining troop territories, crossing areas, and frequency of use can inform the best bridge location. Through the EWT-WTP student mentorship and with help from Wendy Collinson-Jonker (EWT) and Sandra Jacobson (US Forest Service Wildlife Biologist), Courtney has visited potential bridge installation sites in KwaZulu Natal and is currently studying road crossing hotspots to determine where bridges would be most likely to be used as intended.

Once suitable sites have been identified, we can begin the exciting part – testing the design identified as most suitable (the ladder bridge) on free-ranging monkeys. Watch this space for updates! All information and research updates can also be found on Instagram (@wildways_sa), Facebook (Wild Ways South Africa), and EWT platforms.

Courtney Maiden, Endangered Wildlife Trust MSc Student

Over 750,000 km of roads crisscross South Africa, and the country’s natural habitats and wildlife are gravely threatened by further road development. Furthermore, with the anticipated increase of vehicles on the roads over the coming years, the likelihood of more wildlife-vehicle collisions is worrying. The Vervet Monkey (Chlorocebus pygerythrus) has adapted to thrive in human-altered landscapes. However, this also means they face many risks from humans and their activities. Vervet monkeys face daily challenges living in an urban environment due to increasing habitat loss and fragmentation. The clearing of treed areas for roads and other purposes forces monkeys to the ground, increasing their risk of being hit by vehicles. An important first step in reducing this outcome is the design of safe and cost-effective structures by which animals can safely cross the road.

Over the past two decades, wildlife crossing structures have been installed to facilitate wildlife movement over or under roads and railways to connect habitats and reduce roadkill. These structures are often custom-designed for each site and according to the needs of the targeted species. Yet, less than a handful of studies look at the effectiveness of different measures in reducing wildlife‐vehicle collisions in South Africa. Moreover, systematic assessments on designing safe and cost‐effective crossing structures for wildlife have not been carried out to date in our country, despite their importance in preventing Vervet Monkeys and other animals from becoming roadkill.

In March 2022, Courtney Maiden from the Endangered Wildlife Trust tested three different canopy bridge designs for Vervet Monkeys to identify one standardised design for the benefit of free‐ranging Vervet Monkey troops. The observational experiments took place at the Centre for the Rehabilitation of Wildlife (CROW) in Durban, where the three bridge designs were installed in two Vervet Monkey enclosures. Testing different canopy bridge designs in an ex-situ environment such as CROW allows us to establish design guidelines that can be used for free-ranging Vervet Monkeys in-situ (in their natural habitat). These ex-situ experiments are vital for understanding how Vervet Monkeys behave on different canopy bridge designs and identifying the most suitable bridge design to increase the likelihood of the bridges being used in the wild.

The bridges were made using polypropylene rope and recycled plastic. The design is adaptable to varying installation lengths, heights, and crossing environments. By observing the monkeys directly and using camera trap footage, we found that the ladder bridge was used most often and showed great potential for being the most suitable design.

The positioning of any wildlife crossing structure is equally as important as its design. As the Vervet Monkey is a territorial species with daily foraging paths, installing canopy bridges along preferred movement pathways is vital for maximum benefit. Examining troop territories, crossing areas, and frequency of use can inform the best bridge location. Through the EWT-WTP student mentorship and with help from Wendy Collinson-Jonker (EWT) and Sandra Jacobson (US Forest Service Wildlife Biologist), Courtney has visited potential bridge installation sites in KwaZulu Natal and is currently studying road crossing hotspots to determine where bridges would be most likely to be used as intended.

Once suitable sites have been identified, we can begin the exciting part – testing the design identified as most suitable (the ladder bridge) on free-ranging monkeys. Watch this space for updates! All information and research updates can also be found on Instagram (@wildways_sa), Facebook (Wild Ways South Africa), and EWT platforms.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge