By Andreas Wilson-Spath• 15 December 2020

The Okavango Delta, Botswana. (Photo: EPA / Gernot Hensel)

For a distance of some 150km, Canadian company ReconAfrica’s oil and gas prospecting concessions border the Kavango River, a crucial source of water in a semi-arid area and the lifeline for one of Africa’s greatest concentrations of wild species in the Okavango Delta into which it discharges.

The fate of one of Africa’s most valuable ecosystems may depend on results from wells being drilled deep into the bedrock beneath the Kalahari of northern Namibia and Botswana in the hunt for a petroleum reservoir.

If the search by Canadian oil and gas company ReconAfrica is successful, the region could be irrevocably transmogrified by networks of access roads, truck traffic and heavy machinery, pipelines, drill rigs and hundreds of oil and gas production wells.

A group of yellow-billed storks and other birds feed on small fishes in the flooded grassland in the Kwedi concession of the Okavango Delta, about 30km north of Mombo, Botswana. (Photo: EPA / Gernot Hensel)

For ReconAfrica it would mean “the largest oil play of the decade” and immense financial profits. For social and environmental justice activists it spells unmitigated disaster.

The role played by the Namibian government (a 10% shareholder in ReconAfrica’s Namibian exploration concession) is of grave concern. While the petroleum company is vocally proclaiming that they are on the brink of a major discovery, the Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME) is downplaying potential risks and suggesting that the focus is merely on “exploration”.

Does this mixed messaging suggest misinformation on the part of ReconAfrica to lure potential investors? Is the government trying to obfuscate what’s really happening in the region? Is this then a case for the US Securities Exchange Commission to investigate?

ReconAfrica holds exploration licences for an area of more than 25,000km² in north-eastern Namibia and a further 9,900km² across the border in Botswana. Beneath this land lies the Kavango Basin, a geological mega-structure which the company’s experts conservatively estimate to contain 120 billion barrels of oil equivalent.

To put the claimed size of this deposit into context, the largest oil field in history, Saudi Arabia’s Ghawar Field, is believed to have held a total of 88 to 104 billion barrels of oil, while the country estimated to have the biggest proven reserves is Venezuela at about 303 billion barrels.

A group of giraffes in the Kwedi concession of the Okavango Delta. (Photo: EPA / Gernot Hensel)

In a press release, the MME suggests that the “necessary environmental impact permits” are in place, but opponents question the efficacy and thoroughness of the process and argue that ReconAfrica’s environmental impact assessment (EIA) falls short of legal requirements.

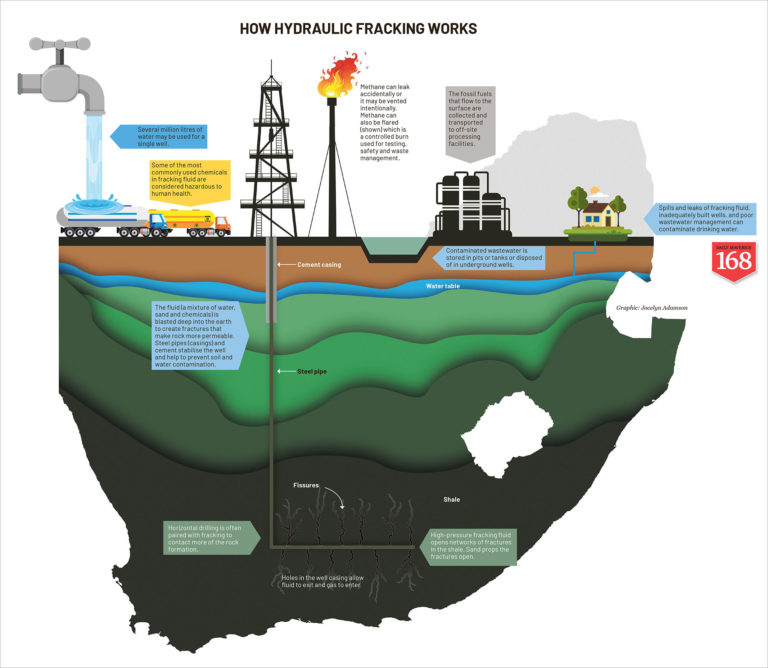

One major concern is that the exploitation of oil or gas deposits may require the use of hydraulic fracking technology, which involves injecting pressurised, water-based, chemical-laced fluid into wells to help release hydrocarbons tightly held in so-called unconventional deposits.

The myriad dangerous effects of fracking, from its need for vast amounts of water to the potential for artificial earthquakes, the contamination of ground and surface water and the poisoning of humans as well as the natural food chain, are well documented.

In its extremely optimistic communications with the media, ReconAfrica implies that fracking may well be on the cards. Daniel Jarvie, a petroleum geochemist on the company’s technical team, states that its licences in Namibia and Botswana “offer large-scale plays that are both conventional and unconventional”. Such unconventional “plays” would require fracking.

In a 2019 presentation to investors, ReconAfrica compares the Kavango basin to the huge Eagle Ford Shale oil and gas field in Texas and refers to plans for “modern frac simulations”. In the case of the Eagle Ford Shale, fracking at thousands of wells has been linked to air pollution and an increase in seismic activity “33 times the background rate”.

Dr Annette Hübschle of the Environmental Futures Project of UCT’s Global Risk Governance Programme warns that “we should be very concerned about the long-term impacts of fracking on livelihoods, health, ecosystems, biodiversity conservation and especially climate change.”

A hamerkop rests on the branch of a tree in the Kwedi concession in the Okavango Delta. (Photo: EPA / Gernot Hensel)

The MME insists, however, that neither an onshore production licence nor a licence to develop unconventional resources has been applied for or granted. They declare that “no hydraulic fracking activities are planned in Namibia” and that “Recon will not be conducting any fracking activities in the Okavango Delta.”

While the MME seems to imply that what is going on is merely exploration for possible petroleum reserves, ReconAfrica appears ready to move into oil production as soon as possible, noting that once a commercial-scale discovery is declared, their agreement with the Namibian government entitles them “to obtain a 25-year production licence”.

Ultimately, the debate over fracking may be moot as there is little doubt about the overwhelmingly destructive effects of major petroleum production – with or without fracking – in a dry, ecologically-sensitive region.

And that’s without the occurrence of any disasters – an unrealistic expectation from an industry responsible for some of the biggest environmental catastrophes in history, from the Exxon Valdez and Deepwater Horizon to Canada’s tar sands and the devastation of the Niger Delta.

According to Hübschle, “the EIA fails to address the issue of the high volumes of water required for exploration and how the highly toxic and radioactive drill mud will be cleaned and disposed of.”

A threat to people and cultural heritage

A small herd of zebras in the Kwedi concession in the Okavango Delta. (Photo: EPA / Gernot Hensel)

What is indisputable are the risks to which large, industrialised oil production would expose the region.

For a distance of some 150km, ReconAfrica’s concessions border the Kavango River (often referred to as the Okavango River, and called Rio Cubango in Angola), a crucial source of water in a semi-arid area and the lifeline for one of Africa’s greatest concentrations of wild species in the Okavango Delta into which it discharges.

The region as a whole is home to around 200,000 people. The Okavango Delta, which is downstream from the suspected oil field, provides a livelihood for indigenous populations of at least five ethnic groups who rely on the landscape for water, fishing, hunting, wild plant foods, farming and tourism.

Of particular concern are local San communities whose already threatened lifestyle would be deeply impacted by the arrival of the oil industry. What’s more, the area where petroleum production would occur includes Botswana’s Tsodilo Hills — a Unesco World Heritage Site — which is celebrated as the “Louvre of the Desert” and protects over 4,500 San rock paintings, some of which are 1 200 years old.

Hübschle notes that “very few affected parties were consulted by government and the company. While the company is engaging in a winning hearts and minds campaign, there are many affected people who are deeply concerned about their land rights, ability to farm and derive income from community conservancies.”

A threat to wildlife and ecology

A female leopard rests on a termite hill in the Kwedi concession in the Okavango Delta, (Photo: EPA / Gernot Hensel)

A future Kavango Basin oil field not only poses an existential risk to the Okavango Delta, a Unesco World Heritage Site in its own right — Botswana’s most-visited tourist destination and home to a very large and diverse population of animals, including more than 70 species of fish and over 400 species of birds — but it also directly overlaps the world’s largest terrestrial cross-border wildlife sanctuary, the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (Kaza), which straddles the borders of Botswana, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Angola and Zambia.

A source of millions of dollars of income from sustainable ecotourism, the area protects at least four species on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) list of “critically endangered” animals, including the black rhino and the white-backed vulture, seven “endangered” species, including the grey-crowned crane and the African wild dog, as well as 20 species listed as “vulnerable”, such as the martial eagle and Temminck’s pangolin.

The region is also known for its extensive network of migration routes for the planet’s largest remaining elephant population. Studies have revealed that these animals have huge home ranges of nearly 25,000km² and roam across vast distances between Botswana, Namibia, Angola and Zambia.

The disruption of migration corridors by a massive new oil industry infrastructure would not just endanger the survival of the elephant population but is likely to increase detrimental interactions with local human communities.

“If full-scale drilling goes ahead”, says Hübschle, “the outlook for Kaza would be grim. Tourists won’t come on safari to look at oil rigs.”

From a global perspective, extracting vast amounts of fossil fuels from the region will exacerbate the ongoing human-induced climate crisis which is itself threatening the survival of the Okavango Delta as a result of decreasing annual rainfall in the catchment area.

A hippo bull roars in the Kwedi concession in the Okavango Delta. (Photo: EPA / Gernot Hensel)

In a deeper, geological irony, the rocks suspected of containing the oil and gas reserves of the Kavango Basin were deposited in the Permian Period which came to a cataclysmic end in the most extreme extinction event of the Earth’s history that wiped out 90% to 95% of all marine species and 70% of all land organisms.

Digging up and burning oil from these strata will push us even closer to a new global mass extinction.

In its myopic vision, all ReconAfrica sees in the northern Kalahari is money buried underground.

The Okavango Delta, Botswana. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Gernot Hensel)

At a time when the world’s few remaining wild places need all of the protection we can muster when biodiversity is declining rapidly and when global heating is wrecking the world, it’s the kind of vision that undermines the very foundations of our existence.

If we believe in restorative social and environmental justice, we ought to insist that the international fossil fuel industry funds Namibia and Botswana to keep the oil in the ground, to develop renewable energy systems instead and to safeguard their irreplaceable ecosystems. DM

Andreas Wilson-Späth is a part-time freelance writer and ex-geologist who lives and works in Cape Town.