CHASING KAMPALA MAN OP-ED

The long and tricky road to prosecuting wildlife-trafficking kingpin Moazu Kromah and his network

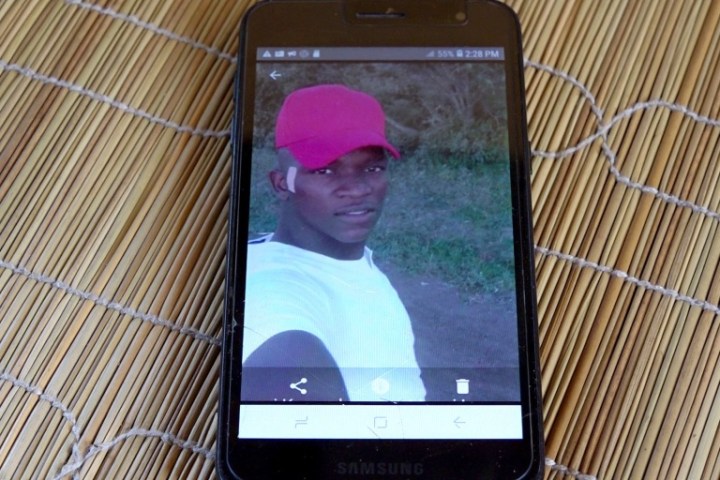

Moazu Kromah at an airport in Entebbe, Uganda, before being extradited to the US. (Photo: Natural Resources Conservation Network)

By Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime | 22 Jun 2022

Moazu Kromah at an airport in Entebbe, Uganda, before being extradited to the US. (Photo: Natural Resources Conservation Network)

By Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime | 22 Jun 2022

A prosecution in New York has ended in a plea bargain by Liberian Moazu Kromah, alleged to be the ringleader of one of the most active wildlife-trafficking syndicates in Africa. Kromah is linked to at least 15 major trafficking cases in Kenya involving more than 30 tonnes of ivory.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Liberian Moazu Kromah – known as “Kampala Man” – led one of the most active wildlife-trafficking syndicates on the African continent before his arrest in the Ugandan capital in February 2017. Just more than five years later, in March 2022, more than 11,000km away from the city in which he based his operation and from which his alias derives, Kromah quietly entered into a plea bargain with the Southern District of New York (SDNY), which is known for tackling high-profile organised crime and corruption cases.

Kromah pleaded guilty to three wildlife-trafficking offences for which he was indicted before being expelled to the US in 2019. His two co-accused made their own plea bargains in the following weeks.

Yet, prosecuting members of Kromah’s network and the individuals who facilitated his shipments of ivory and other wildlife products is, collectively, a far larger task. Out of the 15 major ivory-trafficking cases known to be linked to Kromah’s network which have been prosecuted in the Kenyan courts since 2010, only one so far has secured a conviction. These cases account for more than 30 tonnes of seized ivory. Many of these prosecutions have been ongoing for several years.

The progress of law enforcement and prosecuting authorities in dismantling Kromah’s network provides a window into the challenges that prosecutors face in handling complex wildlife-trafficking cases. It also highlights the role that NGOs can play in supporting prosecutions and building both prosecution and law enforcement capacity.

The Kromah prosecution

Kromah was first arrested in Kampala in February 2017 and about 437 pieces of ivory weighing 1.3 tonnes were seized. The operation was a collaboration between the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) and members of a Ugandan investigative NGO, the Natural Resource Conservation Network (NRCN), who had been investigating Kromah’s network.

The UWA and the NRCN described Kromah as being at “the centre of a vast ring of organised criminals… connected to at least four other major criminal syndicates… supplying the biggest wildlife criminal syndicates worldwide.”

However, the case did not progress through the Ugandan courts, perhaps unsurprisingly: Kromah offered officials present a large cash bribe to make his case disappear and Interpol documents relating to his case were found at his house, suggesting he was used to corrupting criminal justice systems. US authorities initiated another investigation: in 2018, a US confidential informant set up a deal where Kromah and his associates delivered three rhino horns to the US. With a case within the jurisdiction of US authorities secured, Kromah was arrested again in June 2019 and expelled to the US.

Kromah was charged with three counts relating to wildlife trafficking and a fourth money laundering charge. He was charged alongside co-accused Mansur Mohamed Surur, a Kenyan citizen resident in Mombasa, and Amara Cherif, a Guinean based in Conakry. A fourth co-accused, Abdi Hussein Ahmed, remains at large. Surur and Ahmed were also charged with narcotics trafficking for conspiring to sell 10kg of heroin to a buyer in New York, who was actually an undercover agent.

At the time, the arrests and removals of Kromah, Surur and Cherif were seen as a major coup for the prosecution of international wildlife trafficking. The collaboration between a coalition of Ugandan government and law enforcement officials, US agencies and NGOs was described as “unprecedented” and “unparalleled” in expert commentary. International NGO Save the Rhino expressed hope that “the case of Moazu Kromah gives a new example of such positive international collaboration.”

The eventual plea bargain has been met with far less international fanfare. A few weeks after Kromah, Cherif pleaded guilty to the same three counts, after his application to be tried separately from the other defendants was dismissed. This plea bargain came about despite Cherif’s seemingly turbulent relationship with his defence lawyer, whom at one point he accused of attempting to “pressure” him into a plea agreement that he had not had the opportunity to read or understand.

Surur also entered into a plea agreement on 1 June 2022, pleading guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit wildlife trafficking and the narcotics trafficking charge. All three are yet to be sentenced.

In May 2022, the US State Department issued new rewards of up to $1-million for information leading to the arrest of two Kenyans linked to the Kromah case: Abdi Hussein Ahmed, co-accused in Kromah’s original indictment, and Badru Abdul Aziz Saleh, who was identified during the wildlife trafficking investigation of Kromah’s associates and is now wanted on heroin trafficking charges. Saleh was arrested just days after the reward was offered.

Kromah’s criminal network

Kromah’s criminal network was vast, shipping ivory in containers from Mombasa, Kenya and Pemba (in northern Mozambique) and rhino horn by air from Entebbe, Uganda and Nairobi, Kenya. The US indictment of Kromah argues that between 2012 and 2019, his network was responsible for trafficking at least 190kg of rhino horn and at least 10 tonnes of elephant ivory, sourcing these products in Uganda, the DRC, Guinea, Senegal, Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique. However, the true volumes of ivory trafficked by his network are thought to be far higher.

Kromah was operating during a period in which East Africa was experiencing an ivory poaching crisis. In 2013, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) standing committee singled out Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda as being among what became known as the “gang of eight”: the eight countries most heavily implicated in the illegal ivory trade.

Analyses of seized evidence from police operations have argued that, at the time that Kromah was active, the transnational ivory trade was tightly controlled by a very small number of large-scale criminal networks. DNA analysis of ivory seizures, which found tusks from the same individual elephants in separate seizures that were transported through the same ports, concluded that individual traffickers were exporting dozens of large-scale shipments and that the high levels of interconnectivity suggested as few as three major networks were controlling the bulk of the trade, based in Kenya, Uganda and Togo, respectively. Seizures containing matched tusks often had the same modus operandi as ivory trafficking.

Subsequent analysis of seizures between 2002 and 2019, which extended the DNA testing to include close genetic matches between tusks (showing closely related individual elephants in each seizure, indicating the tusks had been poached in the same incidents) suggested that these networks were even more closely connected than initially thought, to the extent that the authors argued that one major organised crime network may have dominated the trade across Kenya and Uganda. All 12 seizures in the study, which had been containerised in Kampala and transited through Mombasa, contained tusks that were genetically linked.

Social network analysis of phone records taken from a Uganda-based wildlife trafficking network (which could not be named in the study because of the possibility of prejudicing ongoing court cases) also found significant cooperation of traffickers across East and West Africa. Trafficking groups were found to be operating closely as “allies of sorts” across the region to supply South-East Asian buyers.

Kenya’s prosecution of cases linked to Kromah

Prosecutions of Kromah’s network and the individuals who facilitated shipments of ivory and other wildlife products for him are ongoing in several countries. In Kenya alone, we reviewed the progress of 15 major ivory-trafficking cases suspected to be linked to this network which have been in prosecution since 2010. While Kromah’s operation spanned East and West Africa, Kenya was a key conduit for ivory shipments, particularly from the port of Mombasa.

Many more linked cases, some including smaller seizures of ivory and other wildlife products, are known to be in progress, both in Kenya and in other East African countries. These 15 were selected to demonstrate the large-scale logistical capacities of the Kromah network and the typical modes of trafficking used. All 15 relate to a seizure of more than (or, in one case, close to) one tonne of ivory.

View on SCRIBD

Collectively, all these prosecutions have so far resulted in the conviction of only two people: Fredrick Sababu Mungule, a clearing agent, and James Ngala Kassiwa, a Kenya Revenue Authority officer. Mungule and Kassiwa were convicted in March 2022 in relation to two seizures, one of more than three tonnes of ivory in Mombasa in 2013, the other of more than a tonne in Hong Kong, shipped from Mombasa several days before. They received two-year sentences and it is understood that they will not appeal.

The fact that these convictions came at the same time as Kromah’s guilty pleas in New York suggests that Mungule and Kassiwa may have chosen not to appeal for fear that evidence provided in the plea bargain could result in much longer sentences in an appeal procedure.

Mungule and Kassiwa’s convictions are currently the only successful major prosecution of international wildlife trafficking in Kenya.

The 2016 conviction of Feisal Mohamed Ali, a transporter and facilitator suspected to be linked to Kromah, was overturned on appeal. The appeal ruling cited several trial irregularities, such as the prosecution providing no witness testimony linking the truck that Feisal supposedly was driving to the seized ivory, and no testimony or forensic evidence linking Feisal to the ivory. Yet the seizure for which Feisal was originally convicted demonstrates clearly how interlinked major ivory seizures have been: DNA analysis of this seizure found genetic matches with 24 others.

Many of these cases have seen considerable delays and adjournments. The conviction of Mungule and Kassiwa took nine years, with a third accused dying in the interim. Their conviction came just months after the same pair were acquitted in relation to another 2013 ivory seizure. In another case, which has now entered its seventh year, the court sat 29 times before the first witness testified, more than two years after the first arrests. These adjournments arise for a variety of reasons, including issues with evidence disclosure, absent witnesses and frequent changes of prosecutors assigned to cases.

Similar courtroom delays are seen in other jurisdictions. A seizure of more than three tonnes of ivory and more than 400kg of pangolin scales in Kampala in January 2019, linked to Kromah, has likewise faced numerous obstacles in the Ugandan courts. As hearings were repeatedly postponed, the prosecution process dissolved, in part due to the Covid-19 pandemic but also because interpreters and court officials were unavailable. The defendants, released on bail, absconded, and prosecutors were compelled to adjourn the case indefinitely pending their rearrest.

In none of the 15 cases reviewed was the ultimate owner of the seized ivory established. The prosecutions, such as those of Feisal, Mungule and Kassiwa, have primarily targeted facilitators with more minor roles, such as clearing agents and transporters.

In one case, a shipping agent named Ephantus Gitonga Mbare was prosecuted in relation to a tonne of ivory seized in Mombasa in 2016. “It is astounding that the only person charged in relation to the seizure was a lowly shipping agent,” reported Wildlife Direct, an NGO that runs a court-monitoring programme recording the prosecutions of wildlife cases in Kenya.

Mbare’s peripheral role in the case was what secured his acquittal, since it could not be proven that he knew that the shipment contained wildlife products. The trial magistrate noted that the prosecution had failed to identify other people involved in the case. In three of the cases reviewed for this analysis, no one has been charged.

There are several links between the accused persons in different cases. Mungule, one of the two persons convicted, was linked to two other previous ivory shipments. James Njagi, former Kenya Revenue Authority head of verification at Mombasa Port, was implicated in two separate prosecutions. Njagi was charged in relation to a 2014 seizure made in Mombasa. A witness testified that Njagi’s ID was used when releasing the container holding the ivory for shipment. Similarly, in relation to a 2011 seizure in Mombasa, Njagi’s name was identified on a verification form for the shipment found to contain ivory. Njagi argued that the document was a forgery.

In several cases the same vehicles and drivers, clearing agents and methods of smuggling crop up repeatedly. In two cases, the clearing agent used was Siginon Freight Services, a company owned by the son of former Kenyan president Daniel Arap Moi.

In the view of Wildlife Direct, the number of links between the accused persons in different major ivory cases prosecuted in Kenya suggests the existence of “a cartel controlling major shipments of ivory out of Kenya”. Their report concluded that based on the rate of convictions in major ivory cases, “this cartel, if it exists, remains beyond the reach of the law”.

Systemic challenges in the prosecution of complex wildlife trafficking cases

Kromah’s conviction in New York is just one part of the arduous, less well-publicised work of untangling the networks of his associates and facilitators. For some commentators, the delays in prosecuting these cases are an unavoidable consequence of prosecution authorities – some of them institutions still in their infancy – being restricted in terms of personnel, resources and capacity.

Shamini Jayanathan, an adviser on environmental crime prosecutions at the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, argues that “failures in prosecution disclosure, lack of organisation of witnesses, exhibits and lack of coordination with investigators are inevitable in the context of such limited prosecution resources”.

There is also the role of corruption in delaying – and, in some cases, derailing – court processes, as is suspected to have been the case in the initial Ugandan prosecution of Kromah.

In this context, NGOs often play a role in assisting and monitoring prosecutions, including in the prosecution of Kromah and his associates. Court-monitoring programmes, in which trained observers record the outcomes of wildlife crime cases, identify potential issues in court proceedings and help build prosecutorial capacity, have had a demonstrable impact in some East and southern African countries.

Such programmes can follow two different approaches. First, some NGOs have taken on a role of monitoring the progress of wildlife crime cases in courtrooms, publicising the outcomes of these prosecutions and attempting to prevent corruption or weak prosecutions through public pressure. The work of Wildlife Direct’s “Eyes in the Courtroom” project and the sharing of public information about ivory prosecutions through SEEJ-Africa (Saving Elephants through Education and Justice) both follow this first model.

Second, other NGOs have taken on more of a capacity-building role, working closely with prosecuting authorities to identify where prosecutions are weakest and to tackle these shortcomings.

Outside of the courtroom, other NGOs are providing support to investigations and have been instrumental in gathering evidence on wildlife-trafficking networks. This has been influential, for example, in the role of the Natural Resource Conservation Network in investigating Kromah before his 2017 arrest, as well as in the investigations of other major wildlife traffickers, such as Yang Fenglan (the “Ivory Queen”) in Tanzania and Yunhua Lin, a major trafficker in Malawi.

As prosecutions of Kromah’s associates continue to face stumbling blocks, NGOs and governments can consider how these partnerships may help overcome the challenges that lead to many prosecutions being delayed or ultimately unsuccessful. DM

This article appears in the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime’s monthly East and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin. The Global Initiative is a network of more than 500 experts on organised crime drawn from law enforcement, academia, conservation, technology, media, the private sector and development agencies. It publishes research and analysis on emerging criminal threats and works to develop innovative strategies to counter organised crime globally.