Posted on 24 December, 2018 by Guest Blogger in Hunting, Opinion Editorial, Wildlife and the Opinion Editorial post series.

Opinion post by Pragmatic Alternative to Trophy Hunting Facebook group

When left to nature, the delicate balance of wild ecosystems ensures survival of the fittest, as long as national parks and reserves – set aside for wildlife – are protected and connected via safe migration corridors. Predators help to maintain the healthy balance of wild ecosystems by killing only the slowest, weakest individuals.

Trophy hunters target the largest or rarest animals they can find – or those with the biggest horns, tusks or manes. Yet both science and common sense tells us that that goes against nature’s law of survival of the fittest. The reason dominant males survive to grow to be the largest and fittest individual is due to strong genes that have been passed down to them through natural selection – achieved through males fighting to decide dominance and ensure the strongest genes are passed on.

In the wild, when natural, favourable occurrences cause overpopulation, natural processes work to stabilise that population. Starvation and disease are nature’s ways of ensuring that healthy, strong animals survive so that the strongest genes are passed on to future generations. When migration corridors are blocked and natural dispersal is prevented overpopulation will result – this is not however a natural occurrence. It’s vital that safe migration corridors are kept open to allow natural dispersal and avoid overpopulation of species.

It’s claimed that trophy hunting is a good conservation tool, but after many decades trophy hunting has done nothing to solve the causes of poaching in Africa. This is one of the main reasons the KAZA Trans Frontier Conservation Area is not functioning as intended. Often, trophy hunting concessions block ancient wildlife migration corridors, and poaching is uncontrolled even in the countries where trophy hunting goes on – making safe dispersal across the KAZA TFCA dangerous for elephants – which is why so many have been taking refuge in the relative safety of Botswana.

Yet organisations such as WWF and Peace Parks – founders of KAZA – support trophy hunting as a ‘useful conservation tool’ when in fact it causes more problems than it solves. According to the World Wildlife Fund’s 2018 report, global wildlife population shrank by 60% between 1970 and 2014! Trophy hunting has been going on for decades but has not helped to stop poaching inside the National Parks of Africa. It doesn’t help to solve the causes of poaching, and yet strong gene pools are depleted when trophy hunters target the biggest specimens from the ever dwindling populations of wildlife. This goes to show that a new way of protecting wildlife is urgently needed – rather than continuing to rely on trophy hunting as a conservation tool.

Where the boundaries of National Parks are surrounded by hunting concessions, individuals from the communities, living in the area, are employed seasonally by the hunting industry, and ‘game meat’ is distributed to poor communities during the hunting season. But those communities are not lifted out of the poverty trap – and encouraging demand for ‘bushmeat’ leads to more poaching – not less – inside the National Parks.

Most trophy hunters push for more trade of ivory, rhino horn and lion bones to be permitted. This puts elephants, rhinos and lions at greater risk since encouraging demand, in the insatiable markets of Asia (the majority of consumers are in Asia these days), for body parts of endangered or threatened species, only leads to more poaching, supported by powerful trafficking syndicates operating across Africa. Funding from trophy hunting does go towards supporting anti poaching patrols and de-snaring operations, but it does not help to solve the causes of poaching. It simply drives a never ending vicious cycle.

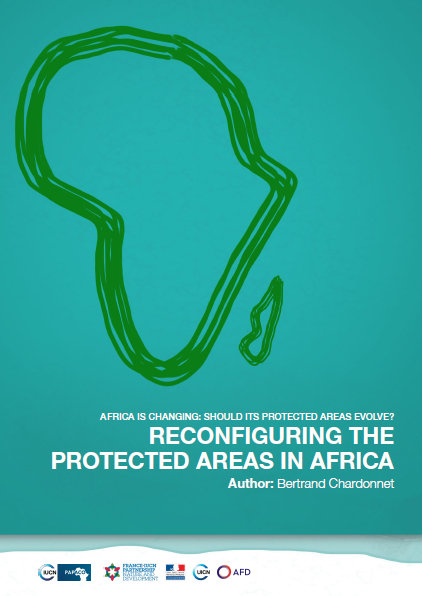

Trophy hunting outfitters get paid overseas for several hunts over a typical 2 – 3 week hunting safari and only a fraction of the hunting fees return to Africa. The money from trophy hunting that does come into Africa pales in comparison to the billions generated from photo tourism each year. Revenues from trophy hunting constitutes only a fraction of a percent of GDP in African countries where it’s practiced and almost none of that ever reaches rural communities.

A far better way forward for Africa, would be to begin to phase out unsustainable trophy hunting and ensure that more revenue from photo tourism goes towards supporting communities living close to National Parks, in creating protective community-run conservancies inside buffer zones, or in failed hunting concessions, for establishing various eco ventures – in exchange for their help in protecting the wildlife in and around the protected parks.

Regenerative tourism should be encouraged whereby tourists wishing to help support those communities, visit the community-run conservancies to contribute in some way – either helping to establish eco ventures, buying crafts or going on bird watching tours (until wildlife returns to the conservancies – which it will in time, once protected).

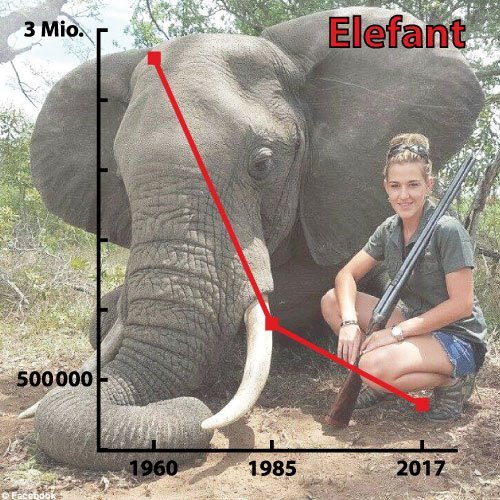

Statistics of elephant population, with hunter and dead elephant as background

Source :Facebook, unknown

Examples of why trophy hunting is not true conservation:

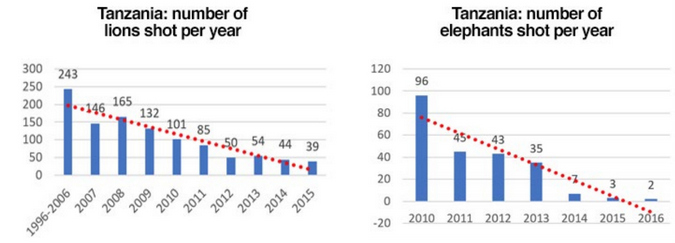

Lion populations have declined sharply in the last three decades, across Africa, due to threats such as habitat loss, retaliatory killings, snares set by poachers and increasing demand for lion bones and body parts from China. Populations in many range states are already dangerously low and yet hundreds of the largest males are trophy hunted each year. Not only does this remove the strongest, dominant males, but it often forces females – left with older cubs to feed and wanting to protect them from other male lions – to leave the parks and attack livestock which is easier to kill.

Very young cubs, unable to walk long distances, will simply be killed by less dominant males that take over the pride. Hunting regulations are often broken whereby pride males with cubs are targeted as ‘trophies’ – since they happen to be the largest lions around – with the biggest manes. By removing the fittest, resistance to deadly diseases is also depleted -nwhich can cause the loss of entire prides.

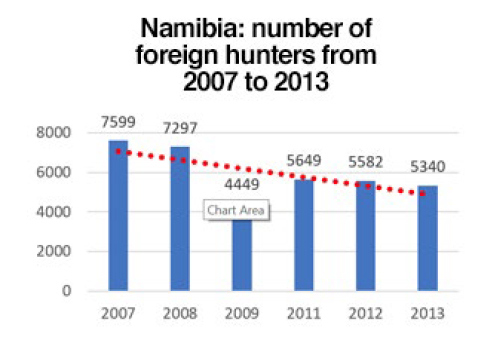

Elephant trophy hunting also not only depletes strong gene pools but also removes the older bulls and matriarchs with knowledge needed for survival in the wild. Many more elephants are now tuskless these days, which shows that trophy hunting is not sustainable in the long term – since the more the biggest tuskers are removed, the smaller the ‘trophies’ become. In that way, the rule of survival of the fittest is being overruled. Elephants evolved with tusks for a reason.

Tuskless elephants weaken their chances of survival since they need their tusks – to strip bark from trees and dig for water in dry riverbeds to survive long dry seasons, to defend their young from predators, and in the case of males with the largest tusks, as a show of dominance and to fight off rivals. Elephants are also family-oriented, sentient beings. Herds of female elephants are led by a matriarch and dominant bull elephants teach manners and pass on knowledge to younger males. So much is being lost each time a large bull or matriarch is trophy hunted or poached for their tusks!

True conservation should involve local communities in ways that will develop sustainable livelihoods and independence – and help to solve the causes of poaching.

The international community needs to help to solve the causes of poaching by calling for the urgent elimination of all demand for endangered/threatened species or their body parts. Interpol needs to help to remove the trafficking syndicates and stop smuggling through porous borders to help end the poaching crisis in Africa.

Rural villagers living alongside wildlife need support from grass roots NGOs who can help to surround villages, fields and bomas with effective elephant and predator proof fencing – to prevent human-wildlife conflict. Community members would need to be trained to maintain and protect the fencing on behalf of each community.

Once fields are well protected, environmentally-friendly farming methods that protect soils and increase yields – to ensure food security, steady incomes, and prevent deforestation – need to be taught. Holistic grazing and mob grazing methods need to be adopted to regenerate grasslands and predator-proof, mobile bomas used to allow grass to recover as livestock is kept moving to avoid overgrazing. Insurance herds should be kept by communities to compensate for losses.

These are self sustaining solutions that only need initial funding and expert advice to set up and get them running successfully. Grassroots NGOs need funding from many different sources to enable them to give a hand up, rather than hand downs, ensuring a better way forward which can be achieved without relying on seasonal funding from trophy hunters who target the biggest endangered or threatened species.

In arid areas that are used seasonally as migration corridors by elephants, where farming fails repeatedly, land should be set aside for wildlife and communities helped to set up community-run lodges and earn extra revenue from carbon credit schemes while helping to protect forests, as well as earning income from various eco ventures such as beekeeping and craft-work.

SOURCES

• IUCN/PACO: Big Game Hunting in West Africa. What is its contribution to conservation? IUCN, Cambridge, 2009, ISBN: 978-2-8317-1204-8

• Trophy Hunting and Sustainability: Temporal Dynamics in Trophy Quality and Harvesting Patterns of Wild Herbivores in a Tropical Semi-Arid Savanna Ecosystem

• Herbivores, Sustainability, and Trophy Hunting in the Matetsi

• Get the Facts About Trophy Hunting

Illegal hunting practices:

• Shooting into breeding herds (Conservancy Namibia/WWF)

• Killing Collared Elephants

• Trophy Hunting Fails to Show Consistent Conservation Benefits

• Big Game Hunting in Africa is Economically Useless (IUCN)