Here a radio piece on Robben Island MPA

https://omny.fm/shows/weekend-breakfast ... ected-area

Marine Protected Areas (MPA)

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5862

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5862

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

Re: Marine Protected Areas (MPA)

https://theconversation.com/robben-isla ... ica-118794

Robben Island joins list of 20 new protected marine sites in South Africa

June 25, 2019 4.43pm SAST

Author

Alison Kock

Marine Biologist, South African National Parks (SANParks); Institute for Communities and Wildlife in Africa, University of Cape Town, South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity

Disclosure statement

Alison Kock works for the Cape Research Centre, South African National Parks. She receives funding from the Table Mountain Fund. She is affiliated with the National Marine Biodiversity Scientific Working Group, Institute for Communities and Wildlife in Africa and the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity.

Partners

The Conversation is funded by the National Research Foundation, eight universities, including the Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Rhodes University, Stellenbosch University and the Universities of Cape Town, Johannesburg, Kwa-Zulu Natal, Pretoria, and South Africa. It is hosted by the Universities of the Witwatersrand and Western Cape, the African Population and Health Research Centre and the Nigerian Academy of Science. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is a Strategic Partner. more

South Africa’s Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries recently declared 20 marine sites as protected areas. One of them is Robben Island, the site of the prison where anti-apartheid activists including Nelson Mandela were jailed for decades. The Conversation’s Nontobeko Mtshali asked Alison Kock to explain the significance and what the decision means for the area and surrounding environment.

What is a marine protected area and are these unique to South Africa?

Marine protected areas are geographically distinct regions of the ocean that are given special protection under law. They are used worldwide to address over-exploitation of marine resources and safeguard them for future generations.

In the context of South Africa, marine protected areas are used to protect marine species, habitats and cultural heritage. They’re also designed to restore over-exploited marine stocks, promote research and eco-tourism and protect coastal and offshore habitats. South Africa has 136 coastal and marine habitat types, from the coastal nesting grounds of leatherback and loggerhead turtles of iSimangaliso, to the unique coral and gravel habitats of the Amathole Offshore marine protected area. The addition of the new protected area network means that 90% of these habitat types are now protected.

South African marine experts combined the best available scientific information, strategic thinking and a strong participatory process to create a network of marine protected areas that conserves ecosystems, rather than individual species.

What’s the significance of a site being declared as a marine protected area?

South Africa already had 23 marine protected areas. It’s nearly doubled this by adding a new network of 20 under an initiative to unlock the country’s blue economy known as Operation Phakisa. This means that 5.4% of South Africa’s territorial waters are now conserved, compared to 0.4% before the new network was proclaimed.

It falls short of the 10% goal by 2020 that is promoted by the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. The goal is a global call to action to sustainably manage and protect marine and coastal ecosystems. Despite the country’s short fall, it’s better than the global average of 3.6%.

Furthermore, a global review of 144 scientific studies found that for marine wildlife to be adequately conserved and for people to continue to benefit from the ocean, 30% of the ocean needs to be protected by 2030.

What are the environmental, social and economic affects of doing this?

Marine protected areas should have ecological, social and economic goals. The way these protected areas are identified and managed has improved over the years. In the past, marine protected areas were often declared using only environmental criteria. There was little or no contribution from local communities and other stakeholders. This led to conflict between people who depended on the regions to make a living and those trying to enforce the protected area status. Ultimately, this had a negative impact on the effectiveness of trying to protect areas.

But that’s changing. Now the process of declaring a new marine protected area network involves extensive consultations between various industries. These include fisheries, mining, aquaculture, tourism industries and local communities.

The impact on communities – economically and socially – differs as each marine protected area has its own set of priority objectives. Take Robben Island, located in Table Bay adjacent to the City of Cape Town, which is on the latest list. It has three priority objectives: to protect the breeding and feeding area of endangered seabirds like African penguins, to help rebuild important abalone and west coast rock lobster stocks, and to promote the area for tourism and protect the area’s cultural heritage.

What’s supposed to be done now? Are there monitoring and evaluation measures in place? Does South Africa have the capacity to do this properly?

There’s a real danger that the protections won’t be enforced – or become paper parks. This is when marine protected areas only exist on maps and in legislation, but offer little real protection.

To avoid this happening marine protected areas have to be adequately funded, staffed and have community support. In addition, monitoring programmes must be put in place. These must measure whether marine protected areas meet their ecological, economic and social objectives. This needs to be coupled with an effective compliance and enforcement strategy.

Generally speaking, marine conservation and protection are underfunded in South Africa and sustainable funding models haven’t yet been developed. But with the support of other government departments, South African Police Services, industries and NGOs, the country’s managed to implement compliance and long-term monitoring programmes.

An example of an effective, long-term monitoring programme is the multi-disciplinary and multi-institutional project in Algoa Bay that monitors ecosystem change. The project is important because it generates essential knowledge for site management and sustainable development.

But more needs to be done. New innovative technologies such as vessel monitoring systems, remote cameras and drones should be used for better surveillance and effective compliance. In addition, marine protected area management has to take a more human-centred approach and the benefits of protected areas have to be shared more equitably.

The Betty’s Bay marine protected area recently employed local community members to help scientists and managers monitor fish populations. This has led to a greater understanding of the goals of the protected area and improved the relationship between the community and management authority.

Robben Island joins list of 20 new protected marine sites in South Africa

June 25, 2019 4.43pm SAST

Author

Alison Kock

Marine Biologist, South African National Parks (SANParks); Institute for Communities and Wildlife in Africa, University of Cape Town, South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity

Disclosure statement

Alison Kock works for the Cape Research Centre, South African National Parks. She receives funding from the Table Mountain Fund. She is affiliated with the National Marine Biodiversity Scientific Working Group, Institute for Communities and Wildlife in Africa and the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity.

Partners

The Conversation is funded by the National Research Foundation, eight universities, including the Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Rhodes University, Stellenbosch University and the Universities of Cape Town, Johannesburg, Kwa-Zulu Natal, Pretoria, and South Africa. It is hosted by the Universities of the Witwatersrand and Western Cape, the African Population and Health Research Centre and the Nigerian Academy of Science. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is a Strategic Partner. more

South Africa’s Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries recently declared 20 marine sites as protected areas. One of them is Robben Island, the site of the prison where anti-apartheid activists including Nelson Mandela were jailed for decades. The Conversation’s Nontobeko Mtshali asked Alison Kock to explain the significance and what the decision means for the area and surrounding environment.

What is a marine protected area and are these unique to South Africa?

Marine protected areas are geographically distinct regions of the ocean that are given special protection under law. They are used worldwide to address over-exploitation of marine resources and safeguard them for future generations.

In the context of South Africa, marine protected areas are used to protect marine species, habitats and cultural heritage. They’re also designed to restore over-exploited marine stocks, promote research and eco-tourism and protect coastal and offshore habitats. South Africa has 136 coastal and marine habitat types, from the coastal nesting grounds of leatherback and loggerhead turtles of iSimangaliso, to the unique coral and gravel habitats of the Amathole Offshore marine protected area. The addition of the new protected area network means that 90% of these habitat types are now protected.

South African marine experts combined the best available scientific information, strategic thinking and a strong participatory process to create a network of marine protected areas that conserves ecosystems, rather than individual species.

What’s the significance of a site being declared as a marine protected area?

South Africa already had 23 marine protected areas. It’s nearly doubled this by adding a new network of 20 under an initiative to unlock the country’s blue economy known as Operation Phakisa. This means that 5.4% of South Africa’s territorial waters are now conserved, compared to 0.4% before the new network was proclaimed.

It falls short of the 10% goal by 2020 that is promoted by the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. The goal is a global call to action to sustainably manage and protect marine and coastal ecosystems. Despite the country’s short fall, it’s better than the global average of 3.6%.

Furthermore, a global review of 144 scientific studies found that for marine wildlife to be adequately conserved and for people to continue to benefit from the ocean, 30% of the ocean needs to be protected by 2030.

What are the environmental, social and economic affects of doing this?

Marine protected areas should have ecological, social and economic goals. The way these protected areas are identified and managed has improved over the years. In the past, marine protected areas were often declared using only environmental criteria. There was little or no contribution from local communities and other stakeholders. This led to conflict between people who depended on the regions to make a living and those trying to enforce the protected area status. Ultimately, this had a negative impact on the effectiveness of trying to protect areas.

But that’s changing. Now the process of declaring a new marine protected area network involves extensive consultations between various industries. These include fisheries, mining, aquaculture, tourism industries and local communities.

The impact on communities – economically and socially – differs as each marine protected area has its own set of priority objectives. Take Robben Island, located in Table Bay adjacent to the City of Cape Town, which is on the latest list. It has three priority objectives: to protect the breeding and feeding area of endangered seabirds like African penguins, to help rebuild important abalone and west coast rock lobster stocks, and to promote the area for tourism and protect the area’s cultural heritage.

What’s supposed to be done now? Are there monitoring and evaluation measures in place? Does South Africa have the capacity to do this properly?

There’s a real danger that the protections won’t be enforced – or become paper parks. This is when marine protected areas only exist on maps and in legislation, but offer little real protection.

To avoid this happening marine protected areas have to be adequately funded, staffed and have community support. In addition, monitoring programmes must be put in place. These must measure whether marine protected areas meet their ecological, economic and social objectives. This needs to be coupled with an effective compliance and enforcement strategy.

Generally speaking, marine conservation and protection are underfunded in South Africa and sustainable funding models haven’t yet been developed. But with the support of other government departments, South African Police Services, industries and NGOs, the country’s managed to implement compliance and long-term monitoring programmes.

An example of an effective, long-term monitoring programme is the multi-disciplinary and multi-institutional project in Algoa Bay that monitors ecosystem change. The project is important because it generates essential knowledge for site management and sustainable development.

But more needs to be done. New innovative technologies such as vessel monitoring systems, remote cameras and drones should be used for better surveillance and effective compliance. In addition, marine protected area management has to take a more human-centred approach and the benefits of protected areas have to be shared more equitably.

The Betty’s Bay marine protected area recently employed local community members to help scientists and managers monitor fish populations. This has led to a greater understanding of the goals of the protected area and improved the relationship between the community and management authority.

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5862

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67563

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Marine Protected Areas (MPA)

Depends on the new minister

The Sea is not so easy to control

The Sea is not so easy to control

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67563

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Marine Protected Areas (MPA)

Marine protected areas become more than ‘paper parks’ with improved management

By Skyla Thornton for Roving Reporters• 11 April 2021

A large great hammerhead shark (Sphyrna mokarran), about 4m in length, cruises overhead in the Bahamas, Tropical West Atlantic Ocean. (Photo: Alex Mustard / WWF)

South Africa has proclaimed 20 new marine protected areas (MPAs), mirroring worldwide efforts to conserve more marine areas. But a lack of funding and management mean most remain ‘parks on paper’.

Marine protected areas (MPAs) now cover 8% of the world’s oceans and calls for an expansion to 30% by 2030 are laudable. It’s good news for efforts to conserve natural ecosystems and to ensure the sustainable use of our marine resources.

MPAs have expanded and now account for 8% of the world’s oceans. It’s good news for efforts to conserve natural ecosystems and to ensure the sustainable use of our marine resources. Much more needs to be done, however, especially in improving how MPAs are managed.

In December 2020, The Guardian reported that only 1% of the 3,000 supposedly protected areas in the Mediterranean ban fishing. The UK-based publication quoted a study that noted the European Union had failed to halt overfishing, while a 2019 study found that 59% of the MPAs in Europe were trawled by commercial vessels at higher levels than unprotected areas.

According to a September 2019 article in National Geographic, only 4.8% of global MPAs are actively protected and a low 2.2% of global MPAs are classified as highly protected. This is particularly true in less developed countries, such as South Africa, which grapple with the need to balance protecting valuable natural capital with a pressing hunger for jobs and economic development.

Well-intentioned initiatives may not live up to their promise if the conservation of these areas remains underfunded and inadequately managed, as is happening in South Africa.

In October 2018, the South African Cabinet approved 20 new marine protected areas, bringing the total to 41 and increasing the protected areas from 0.4% to about 5% of South Africa’s economic exclusion zone. The move mirrors conservation efforts across the globe, where MPAs have been recognised as buffer ecosystems against natural and human-made shocks, including rising temperatures.

But do these new and expanded MPAs mark real progress for conservation or are they little more than paper parks?

A school of yellowtail at De Hoop Marine Protected Area. MPAs are key to the sustainable use of our marine resources. (Photo: Steve Benjamin)

Roving Reporters spoke to Dr Judy Mann of the South African Association for Marine Biological Research. Mann cautions that, although well-intentioned, South Africa’s expansion of MPAs may not live up to their promise if the conservation of these areas remains underfunded and inadequately managed.

Skyla Thornton: Why are MPAs valued and what purpose do they serve?

Judy Mann: MPAs are an important investment in our future. They protect specific areas, allowing for many species of fish to thrive. This abundance in turn benefits local fisheries. In addition, they provide a protected space for endangered species to be nurtured, biodiversity to be created and a natural balance to be restored. They also have a critical value in terms of protecting the ocean floor against mining, which can be exploitative. In a unique way, MPAs protect the many biomes of our oceans in a network that can benefit not only the life within oceans, but life on land as well.

Down to where it’s wetter: De Hoop enchants. ‘Many communities share a genuine desire to protect ocean life and want to prevent the exploitation of their marine resources as a way of guaranteeing an abundance for future generations to enjoy,’ says Dr Judy Mann. (Photo: Steve Benjamin)

Some have no-take zones (no fishing, harvesting or extracting of any marine life). Others have restricted and controlled areas that allow fishing with permits (including subsistence fishing) and various recreational activities.

Thornton: What is the situation with MPAs in South Africa?

Mann: There are currently 41 MPAs around mainland South Africa, covering about 5.4% of our waters. While these all exist on paper, the effectiveness of their management is variable. Some are very well-managed while others are hardly managed at all. (But) we have a good system to measure how well-managed each MPA is, and every few years a report is produced in which the state of each MPA is discussed.

Under pressure: Dageraad at Stilbaai. These fish have been classified as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. MPAs are vital to conservation efforts. (Photo: Steve Benjamin)

Thornton: What happens when an MPA is declared, but there is no follow-through from the government in terms of funding and proper management?

Mann: The areas you are referring to are often called “paper parks”. These types of areas are where we continue to see destruction and exploitation due to a lack of regulation and funding, as well as inadequate management. “Paper parks” are an unfortunate occurrence, especially when it would benefit our coast the most if we had a network of marine protected areas to protect a variety of ocean ecosystems and habitats.

Thornton: Is there a way to ensure paper parks cease to exist, particularly from a political perspective?

Mann: Paper parks exist when an MPA is proclaimed, but not managed. Some are declared in an area that is convenient in placement and does not require much effort in terms of management. After proclamation, a management plan needs to be developed to ensure that the designated MPA does not simply become a paper park. It is abundantly clear that there needs to be a genuine political will to change the status quo and protect the environment by following the guidelines and adhering to frameworks that already exist. With this, it becomes easier to allocate funding, resources and manpower to the MPAs.

The Maccassar coastline along False Bay in the Western Cape. (Photo: Peter Chadwick)

Thornton: Some politicians in First World countries see environmental work as a way to get voters on their side. Do you think declaring a paper park can be politically motivated in this way?

Mann: I do believe that there is a genuine desire from many politicians to protect marine environments and that they want to manage them as best they can. Given our history of economic disarray and issues with fund allocation in South Africa, it is difficult to ensure that adequate follow-through happens. Ultimately, I don’t think that the existence of paper parks in South Africa stems from a place of politics, but rather from incapacity and a lack of understanding of the benefits to people of well-managed protected areas.

Thornton: What role does the community play in the existence of MPAs in South Africa?

Mann: Empowering local communities through job creation and other economic benefits is key to adequately managing MPAs, as it automatically reduces conflict with communities living around the areas, particularly those who survive on the local fauna and flora.

Many communities share a genuine desire to protect ocean life and want to prevent the exploitation of their marine resources as a way of guaranteeing an abundance for future generations to enjoy. The best way to approach comprehensive solutions to conserve and protect our oceans is through a focus on inclusivity – not only of local communities, but the youth as well. The issues that exist within human development, such as poverty and unemployment, and the issues surrounding conservation are not mutually exclusive. A successful government approach to these issues needs to be inclusive of both worlds.

Thornton: Can you give some South African examples of well-managed MPAs and paper parks?

Mann: Well-managed MPAs include Stilbaai, De Hoop and Tsitsikamma. Established in 1964, Tsitsikamma is the oldest MPA in Africa and a treasure trove of marine life. As far as paper parks go, all the current offshore (deepsea) MPAs fall into this category as their management plans are still being completed.

Thornton: Besides MPAs, what else is being done to protect South African marine and coastal ecosystems?

Mann: MPAs serve as a baseline and allow for many environments to be protected simultaneously, sustaining various ecosystems and benefiting fisheries. Fisheries management is another important mechanism that is used to regulate and protect certain fish stocks within South African oceans.

Thornton: What is the projection for the expansion of MPAs in South Africa?

Mann: One of the targets of (the UN) Sustainable Development Goal 14 was to conserve at least 10% of coastal and marine areas by 2020. South Africa is working towards this goal carefully, taking into account priority areas for conservation and the needs of people.

Thornton: With limited resources available in South Africa, why is expansion being prioritised, rather than focusing on areas that need urgent protection?

Mann: Expansion is important in terms of ensuring that different biomes are protected, but I do feel that we should also put our resources into ensuring our current MPAs are effectively managed, guaranteeing that communities are involved, as well as focusing on wider stakeholders to optimise the benefits that MPAs can provide.

We also need to focus more on measuring the effectiveness of MPAs in a more comprehensive way and communicating more widely about MPAs, specifically about their role in conservation and human well-being.

Thornton: Ultimately, what should happen?

Mann: It’s clear that MPAs have an important role to play in protecting and ensuring the sustainability of our oceans. But we still have a long way to go in transforming them from “paper parks” into truly sustainable MPAs. The expansion of the country’s MPAs is something to celebrate, but the focus must remain on ensuring current MPAs are effective. To make this happen and to ensure the country’s most vulnerable marine life is protected, communities must be involved, adequate management ensured and proper funding provided.

In times of crisis, South Africans have been able to invoke change as a nation. Now we must invest in the natural capital and wild heritage within our waters, with MPAs providing the “bank accounts” that make this possible. DM

Skyla Thornton is a first-year BSc Earth Sciences student at Stellenbosch University. This story arises from Roving Reporters’ Ocean Watch writing project supported by Youth for MPAS (Y4MPAs) and the Earth Journalism Network (EJN). The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of Y4MPAs or EJN. To submit a story idea for this Ocean Watch series, follow these guidelines and email your story pitch to matthewhattinghdbn@gmail.com

Dr Judy Mann helps people care for the oceans. She has worked for the South African Association for Marine Biological Research (SAAMBR) in Durban since 1992. She was the association’s Director of Education for 10 years, the uShaka Sea World director and the first woman chief executive officer of SAAMBR.

By Skyla Thornton for Roving Reporters• 11 April 2021

A large great hammerhead shark (Sphyrna mokarran), about 4m in length, cruises overhead in the Bahamas, Tropical West Atlantic Ocean. (Photo: Alex Mustard / WWF)

South Africa has proclaimed 20 new marine protected areas (MPAs), mirroring worldwide efforts to conserve more marine areas. But a lack of funding and management mean most remain ‘parks on paper’.

Marine protected areas (MPAs) now cover 8% of the world’s oceans and calls for an expansion to 30% by 2030 are laudable. It’s good news for efforts to conserve natural ecosystems and to ensure the sustainable use of our marine resources.

MPAs have expanded and now account for 8% of the world’s oceans. It’s good news for efforts to conserve natural ecosystems and to ensure the sustainable use of our marine resources. Much more needs to be done, however, especially in improving how MPAs are managed.

In December 2020, The Guardian reported that only 1% of the 3,000 supposedly protected areas in the Mediterranean ban fishing. The UK-based publication quoted a study that noted the European Union had failed to halt overfishing, while a 2019 study found that 59% of the MPAs in Europe were trawled by commercial vessels at higher levels than unprotected areas.

According to a September 2019 article in National Geographic, only 4.8% of global MPAs are actively protected and a low 2.2% of global MPAs are classified as highly protected. This is particularly true in less developed countries, such as South Africa, which grapple with the need to balance protecting valuable natural capital with a pressing hunger for jobs and economic development.

Well-intentioned initiatives may not live up to their promise if the conservation of these areas remains underfunded and inadequately managed, as is happening in South Africa.

In October 2018, the South African Cabinet approved 20 new marine protected areas, bringing the total to 41 and increasing the protected areas from 0.4% to about 5% of South Africa’s economic exclusion zone. The move mirrors conservation efforts across the globe, where MPAs have been recognised as buffer ecosystems against natural and human-made shocks, including rising temperatures.

But do these new and expanded MPAs mark real progress for conservation or are they little more than paper parks?

A school of yellowtail at De Hoop Marine Protected Area. MPAs are key to the sustainable use of our marine resources. (Photo: Steve Benjamin)

Roving Reporters spoke to Dr Judy Mann of the South African Association for Marine Biological Research. Mann cautions that, although well-intentioned, South Africa’s expansion of MPAs may not live up to their promise if the conservation of these areas remains underfunded and inadequately managed.

Skyla Thornton: Why are MPAs valued and what purpose do they serve?

Judy Mann: MPAs are an important investment in our future. They protect specific areas, allowing for many species of fish to thrive. This abundance in turn benefits local fisheries. In addition, they provide a protected space for endangered species to be nurtured, biodiversity to be created and a natural balance to be restored. They also have a critical value in terms of protecting the ocean floor against mining, which can be exploitative. In a unique way, MPAs protect the many biomes of our oceans in a network that can benefit not only the life within oceans, but life on land as well.

Down to where it’s wetter: De Hoop enchants. ‘Many communities share a genuine desire to protect ocean life and want to prevent the exploitation of their marine resources as a way of guaranteeing an abundance for future generations to enjoy,’ says Dr Judy Mann. (Photo: Steve Benjamin)

Some have no-take zones (no fishing, harvesting or extracting of any marine life). Others have restricted and controlled areas that allow fishing with permits (including subsistence fishing) and various recreational activities.

Thornton: What is the situation with MPAs in South Africa?

Mann: There are currently 41 MPAs around mainland South Africa, covering about 5.4% of our waters. While these all exist on paper, the effectiveness of their management is variable. Some are very well-managed while others are hardly managed at all. (But) we have a good system to measure how well-managed each MPA is, and every few years a report is produced in which the state of each MPA is discussed.

Under pressure: Dageraad at Stilbaai. These fish have been classified as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. MPAs are vital to conservation efforts. (Photo: Steve Benjamin)

Thornton: What happens when an MPA is declared, but there is no follow-through from the government in terms of funding and proper management?

Mann: The areas you are referring to are often called “paper parks”. These types of areas are where we continue to see destruction and exploitation due to a lack of regulation and funding, as well as inadequate management. “Paper parks” are an unfortunate occurrence, especially when it would benefit our coast the most if we had a network of marine protected areas to protect a variety of ocean ecosystems and habitats.

Thornton: Is there a way to ensure paper parks cease to exist, particularly from a political perspective?

Mann: Paper parks exist when an MPA is proclaimed, but not managed. Some are declared in an area that is convenient in placement and does not require much effort in terms of management. After proclamation, a management plan needs to be developed to ensure that the designated MPA does not simply become a paper park. It is abundantly clear that there needs to be a genuine political will to change the status quo and protect the environment by following the guidelines and adhering to frameworks that already exist. With this, it becomes easier to allocate funding, resources and manpower to the MPAs.

The Maccassar coastline along False Bay in the Western Cape. (Photo: Peter Chadwick)

Thornton: Some politicians in First World countries see environmental work as a way to get voters on their side. Do you think declaring a paper park can be politically motivated in this way?

Mann: I do believe that there is a genuine desire from many politicians to protect marine environments and that they want to manage them as best they can. Given our history of economic disarray and issues with fund allocation in South Africa, it is difficult to ensure that adequate follow-through happens. Ultimately, I don’t think that the existence of paper parks in South Africa stems from a place of politics, but rather from incapacity and a lack of understanding of the benefits to people of well-managed protected areas.

Thornton: What role does the community play in the existence of MPAs in South Africa?

Mann: Empowering local communities through job creation and other economic benefits is key to adequately managing MPAs, as it automatically reduces conflict with communities living around the areas, particularly those who survive on the local fauna and flora.

Many communities share a genuine desire to protect ocean life and want to prevent the exploitation of their marine resources as a way of guaranteeing an abundance for future generations to enjoy. The best way to approach comprehensive solutions to conserve and protect our oceans is through a focus on inclusivity – not only of local communities, but the youth as well. The issues that exist within human development, such as poverty and unemployment, and the issues surrounding conservation are not mutually exclusive. A successful government approach to these issues needs to be inclusive of both worlds.

Thornton: Can you give some South African examples of well-managed MPAs and paper parks?

Mann: Well-managed MPAs include Stilbaai, De Hoop and Tsitsikamma. Established in 1964, Tsitsikamma is the oldest MPA in Africa and a treasure trove of marine life. As far as paper parks go, all the current offshore (deepsea) MPAs fall into this category as their management plans are still being completed.

Thornton: Besides MPAs, what else is being done to protect South African marine and coastal ecosystems?

Mann: MPAs serve as a baseline and allow for many environments to be protected simultaneously, sustaining various ecosystems and benefiting fisheries. Fisheries management is another important mechanism that is used to regulate and protect certain fish stocks within South African oceans.

Thornton: What is the projection for the expansion of MPAs in South Africa?

Mann: One of the targets of (the UN) Sustainable Development Goal 14 was to conserve at least 10% of coastal and marine areas by 2020. South Africa is working towards this goal carefully, taking into account priority areas for conservation and the needs of people.

Thornton: With limited resources available in South Africa, why is expansion being prioritised, rather than focusing on areas that need urgent protection?

Mann: Expansion is important in terms of ensuring that different biomes are protected, but I do feel that we should also put our resources into ensuring our current MPAs are effectively managed, guaranteeing that communities are involved, as well as focusing on wider stakeholders to optimise the benefits that MPAs can provide.

We also need to focus more on measuring the effectiveness of MPAs in a more comprehensive way and communicating more widely about MPAs, specifically about their role in conservation and human well-being.

Thornton: Ultimately, what should happen?

Mann: It’s clear that MPAs have an important role to play in protecting and ensuring the sustainability of our oceans. But we still have a long way to go in transforming them from “paper parks” into truly sustainable MPAs. The expansion of the country’s MPAs is something to celebrate, but the focus must remain on ensuring current MPAs are effective. To make this happen and to ensure the country’s most vulnerable marine life is protected, communities must be involved, adequate management ensured and proper funding provided.

In times of crisis, South Africans have been able to invoke change as a nation. Now we must invest in the natural capital and wild heritage within our waters, with MPAs providing the “bank accounts” that make this possible. DM

Skyla Thornton is a first-year BSc Earth Sciences student at Stellenbosch University. This story arises from Roving Reporters’ Ocean Watch writing project supported by Youth for MPAS (Y4MPAs) and the Earth Journalism Network (EJN). The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of Y4MPAs or EJN. To submit a story idea for this Ocean Watch series, follow these guidelines and email your story pitch to matthewhattinghdbn@gmail.com

Dr Judy Mann helps people care for the oceans. She has worked for the South African Association for Marine Biological Research (SAAMBR) in Durban since 1992. She was the association’s Director of Education for 10 years, the uShaka Sea World director and the first woman chief executive officer of SAAMBR.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67563

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Marine Protected Areas (MPA)

Marine protected areas are critical to the future of South Africa’s iconic reef species

Opinionista • Christopher DZ Mason • 5 August 2021

How we consume seafood has become an implicitly political act. Our choices are our votes, defining our relationships to the ocean. It’s no longer enough to be motivated by half-price sushi. We need to work harder to know where our seafood comes from and whether or not eating that species can be considered viable.

South Africa’s inaugural Marine Protected Areas Day was on 1 August – a celebration of the 5% of our waters that are protected as sanctuaries for marine life, and a stark reminder that the other 95% of the oceans are not.

The scale makes it easy to lose sight of how the health of a single beach or reef can affect the whole system, or why small pockets of marine protected areas are so important. For this, one needs a zoomed-in view, which is something I’ve been afforded while spearfishing and free-diving along our coast. I’ve seen first-hand the difference that marine protected areas make to the way ocean ecosystems look and feel; how protected areas hold populations of big, mature fish while next door in legal fishing areas these species are far smaller and less abundant.

I’ve come to understand that marine protected areas give us a sense of what the baseline health of an ecosystem should look like, and I’ve also had to confront the difficult moral and ethical questions raised by my contribution to the denuding of these places. All of this has led me to believe that we have come to a point where we need to re-evaluate how we perceive ocean wilderness and consume the animals that come from it.

What’s also clear to me is that how we consume seafood has become an implicitly political act. Our choices are our votes, defining our relationships to the ocean in direct or indirect terms. It’s no longer enough to be motivated by half-price sushi. We need to work harder to know where our seafood comes from – not just the rough area, but the actual environment in which it was found, how it was caught, and whether eating that species can be considered viable.

For some people the answer is “don’t eat fish”. For me, the way forward is only eating what I catch. Of course, this is not possible for most. There are billions of people worldwide who rely on the oceans for food and jobs, who are often in poor coastal communities and don’t have the luxury of choice.

What we all share, however, is the opportunity for growing our relationship with the ocean through active interest and care. It brought me great joy to catch the first fish my daughter ate. She saw the whole animal first, a sleek and handsome yellowtail, and watched as I filleted and cooked it, understanding what it was she was eating when she took the first bite. It was the beginning of her relationship with a fish that had become for a time each summer our primary source of protein. What one feeds one’s family is an intimate and important thing. We’re each allowed to make that choice according to our beliefs and preferences, but regardless of what we choose – soy burgers, fresh fish or beef steaks – our choices have repercussions.

The deeper I pursued a direct relationship with the marine animals we ate, the more I began to see that the fish I was hunting, and the oceans in which they lived, were under far greater stress than I had first understood. For while the fast-growing and seasonally abundant pelagic species like Cape yellowtail proved to be exciting and sustainable green-listed quarry, the large reef fish of the Cape are already in great peril. Their life histories – being long-lived, slow growing and hyperterritorial – make them far more susceptible to fishing pressure.

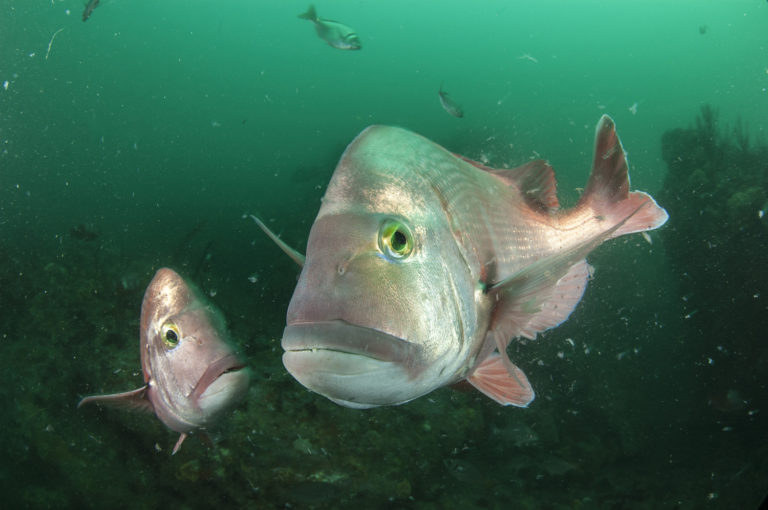

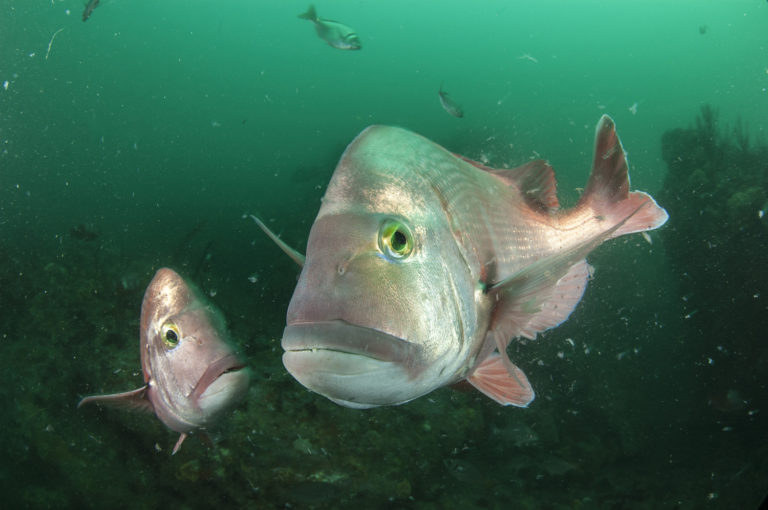

One species that seemed to define the modern plight of the Cape reef fish with vivid and alarming complexity was the Red Roman. Striking and proud in bearing, it is one of the last of the large reef fish to still be seen with some regularity in the great African kelp forests of the Cape.

Traditionally, Red Romans have been highly sought after by line and spearfishermen alike. I remember going as a kid to the East London harbour with my Yiayia (Greek grandmother), who loved nothing more than an early trip to the docks to meet the fishermen on their return, and who prized Red Roman as an eating fish above all others.

These days the Red Roman is listed as near threatened on the IUCN Red List for Threatened Species and a quick Google search shows it’s still easy to buy them from, for example, Fish 4 Africa. It’s also legal for recreational fishermen to catch up to two a day with the correct permit.

But knowing this does not tell the whole story of the Red Roman or its importance as an indicator species in reef systems. Diving along the coast of False Bay, I would sometimes see Red Romans adding their custom splash of colour to the seabed. But they were few and far between compared with the numbers I saw in the “no-take” safe zones of the bay’s marine protected areas. When I started asking fishing friends about whether they thought we should be catching Red Romans, there was a mix of replies, ranging from “we recreational fisherman don’t make nearly as much of an impact as commercial fishermen” (which is true, with the disclaimer that recreational fisherman still make an impact), to “if it’s big and red, don’t shoot it!”

The scale makes it easy to lose sight of how the health of a single beach or reef can affect the whole system, or why small pockets of marine protected areas are so important. For this, one needs a zoomed-in view, which is something I’ve been afforded while spearfishing and free-diving along our coast. I’ve seen first-hand the difference that marine protected areas make to the way ocean ecosystems look and feel; how protected areas hold populations of big, mature fish while next door in legal fishing areas these species are far smaller and less abundant.

I’ve come to understand that marine protected areas give us a sense of what the baseline health of an ecosystem should look like, and I’ve also had to confront the difficult moral and ethical questions raised by my contribution to the denuding of these places. All of this has led me to believe that we have come to a point where we need to re-evaluate how we perceive ocean wilderness and consume the animals that come from it.

What’s also clear to me is that how we consume seafood has become an implicitly political act. Our choices are our votes, defining our relationships to the ocean in direct or indirect terms. It’s no longer enough to be motivated by half-price sushi. We need to work harder to know where our seafood comes from – not just the rough area, but the actual environment in which it was found, how it was caught, and whether eating that species can be considered viable.

For some people the answer is “don’t eat fish”. For me, the way forward is only eating what I catch. Of course, this is not possible for most. There are billions of people worldwide who rely on the oceans for food and jobs, who are often in poor coastal communities and don’t have the luxury of choice.

What we all share, however, is the opportunity for growing our relationship with the ocean through active interest and care. It brought me great joy to catch the first fish my daughter ate. She saw the whole animal first, a sleek and handsome yellowtail, and watched as I filleted and cooked it, understanding what it was she was eating when she took the first bite. It was the beginning of her relationship with a fish that had become for a time each summer our primary source of protein. What one feeds one’s family is an intimate and important thing. We’re each allowed to make that choice according to our beliefs and preferences, but regardless of what we choose – soy burgers, fresh fish or beef steaks – our choices have repercussions.

The scale makes it easy to lose sight of how the health of a single beach or reef can affect the whole system, or why small pockets of marine protected areas are so important. For this, one needs a zoomed-in view, which is something I’ve been afforded while spearfishing and free-diving along our coast. I’ve seen first-hand the difference that marine protected areas make to the way ocean ecosystems look and feel; how protected areas hold populations of big, mature fish while next door in legal fishing areas these species are far smaller and less abundant.

I’ve come to understand that marine protected areas give us a sense of what the baseline health of an ecosystem should look like, and I’ve also had to confront the difficult moral and ethical questions raised by my contribution to the denuding of these places. All of this has led me to believe that we have come to a point where we need to re-evaluate how we perceive ocean wilderness and consume the animals that come from it.

What’s also clear to me is that how we consume seafood has become an implicitly political act. Our choices are our votes, defining our relationships to the ocean in direct or indirect terms. It’s no longer enough to be motivated by half-price sushi. We need to work harder to know where our seafood comes from – not just the rough area, but the actual environment in which it was found, how it was caught, and whether eating that species can be considered viable.

For some people the answer is “don’t eat fish”. For me, the way forward is only eating what I catch. Of course, this is not possible for most. There are billions of people worldwide who rely on the oceans for food and jobs, who are often in poor coastal communities and don’t have the luxury of choice.

What we all share, however, is the opportunity for growing our relationship with the ocean through active interest and care. It brought me great joy to catch the first fish my daughter ate. She saw the whole animal first, a sleek and handsome yellowtail, and watched as I filleted and cooked it, understanding what it was she was eating when she took the first bite. It was the beginning of her relationship with a fish that had become for a time each summer our primary source of protein. What one feeds one’s family is an intimate and important thing. We’re each allowed to make that choice according to our beliefs and preferences, but regardless of what we choose – soy burgers, fresh fish or beef steaks – our choices have repercussions.

The scale makes it easy to lose sight of how the health of a single beach or reef can affect the whole system, or why small pockets of marine protected areas are so important. For this, one needs a zoomed-in view, which is something I’ve been afforded while spearfishing and free-diving along our coast. I’ve seen first-hand the difference that marine protected areas make to the way ocean ecosystems look and feel; how protected areas hold populations of big, mature fish while next door in legal fishing areas these species are far smaller and less abundant.

I’ve come to understand that marine protected areas give us a sense of what the baseline health of an ecosystem should look like, and I’ve also had to confront the difficult moral and ethical questions raised by my contribution to the denuding of these places. All of this has led me to believe that we have come to a point where we need to re-evaluate how we perceive ocean wilderness and consume the animals that come from it.

What’s also clear to me is that how we consume seafood has become an implicitly political act. Our choices are our votes, defining our relationships to the ocean in direct or indirect terms. It’s no longer enough to be motivated by half-price sushi. We need to work harder to know where our seafood comes from – not just the rough area, but the actual environment in which it was found, how it was caught, and whether eating that species can be considered viable.

For some people the answer is “don’t eat fish”. For me, the way forward is only eating what I catch. Of course, this is not possible for most. There are billions of people worldwide who rely on the oceans for food and jobs, who are often in poor coastal communities and don’t have the luxury of choice.

What we all share, however, is the opportunity for growing our relationship with the ocean through active interest and care. It brought me great joy to catch the first fish my daughter ate. She saw the whole animal first, a sleek and handsome yellowtail, and watched as I filleted and cooked it, understanding what it was she was eating when she took the first bite. It was the beginning of her relationship with a fish that had become for a time each summer our primary source of protein. What one feeds one’s family is an intimate and important thing. We’re each allowed to make that choice according to our beliefs and preferences, but regardless of what we choose – soy burgers, fresh fish or beef steaks – our choices have repercussions.

These days the Red Roman is listed as near threatened on the IUCN Red List for Threatened Species. (Photo: Steve Benjamin)

The latter came from Steve Benjamin, a good friend who taught me how to dive. Steve is both a marine biologist and a spearfisher and consciously walks the line that connects the two. It was from him that I started learning about the various fish species we encountered, and which ones I could target. Steve chooses to point his camera rather than his speargun at Red Roman, and has taken some of the most beautiful photos of the species in circulation today, and it was after talking to him about the plight of the Red Roman that I began to realise that it was perhaps because of it’s crimson conspicuousness that the species was so important. It was the last big red fish we were seeing on the reefs; the final warning light in a long line of now missing keystone species.

To understand what all this meant, I turned to another friend who was qualified to give me a real answer – filmmaker and conservation journalist Philippa Ehrlich. Philippa was writing about the urgent need to protect South African reef fish back in 2015 and it was her article that had helped me see the Red Roman in the context of an embattled line fishery. When I asked Philippa about the condition of the reef fish of False Bay now, she started with a story:

“A friend of mine, Lauren de Vos from Save Our Seas Foundation, had been telling me for a long time about these incredible reef fish species that live in South Africa and False Bay. But, I have dived in False Bay for most of my adult life and when I went through her list of fish I realised pretty quickly that the only one I was seeing was the Red Roman. So much of the original diversity had disappeared, which included animals like Red Steenbras, Red Stumpnose, Knifejaw, Jan Bruins, White Steenbras, Galjoen and Musselcracker. What was so shocking was that these were animals that have been gone for a long time. It’s not like they’ve only been fished out in the past 20 to 30 years.”

Indeed, the damage started many decades before, probably when large-scale commercial fishing became popular in the 1950s. By the turn of the century it was already clear to those looking at the data that we had a big problem with our reef fish (also known as linefish) populations. The 2013 edition of the Southern African Marine Linefish Species Profile puts it in plain English: “Following the declaration of an emergency in the South African linefishery in December 2000 and the recognition of the urgent need to rebuild many overexploited linefish stocks, implementation of the species-specific management plans eventually took place during the mid-2000s.”

It’s now clear that those management plans were not good enough and that there is a dire need for more marine protected areas, which act as havens that give fish populations the time and safety to recover. And, despite my despair in having to write this sentence of pure gloom, it’s only getting worse. The WWF Sassi website tells us there has been a dramatic increase in the number of fish taken out of the seas in recent decades, with many linefish species in South Africa being either dangerously overexploited or completely collapsed.

While our approach to harvesting marine life clearly needs careful overhauling, perhaps another part of the problem lies in the language we use to talk about “sea” food. When we think of “stocks” the word connotes a “quantity of something” that can be controlled and may fluctuate up or down. Like livestock, bred commercially, or commodities like whisky, wheat or chocolate, of which one can purchase more when “stocks” run low. Not so for the oceans and the fish in them.

We tend to forget that these are wild animals which we track and capture with ever-increasing technological sophistication in industrial fishing industries. Recreational fishing numbers are also growing, as is our skill in catching fish. When considering terrestrial and marine wilderness areas side by side, the only justifiable method of conservation is then complete protection for marine life within “no-take” sanctuary zones, like we do on land.

If we start thinking about them in the same light as our iconic game reserves, the conversation shifts. What makes a leopard’s life of greater value than a predatory reef fish like a Red Steenbras? The fish can live for up to 55 years, whereas the cat would typically only last 12, but yet the former seems doomed by its own deliciousness.

When asked about the importance of marine protected areas, Steve Benjamin replies in emphatic terms: “The oceans are under a massive amount of pressure, from fishing and industry, and they never get a break. Marine protected areas are like oases in a desert of human disturbance. We really need to treasure these last locations where ecosystems can remain functional and fish can live out their lives in a normal way.”

The idea of a fish living its life in a “normal” way stuck with me. The implication is that for the most part fish continually have their lives affected by humans, through fishing, pollution or habitat destruction. Thinking of fish as animals with a sovereign right to their own full experience of life is not something we’re used to.

But anyone who has seen the Oscar-winning documentary My Octopus Teacher is forced to re-evaluate the narrow and reductive “non-human” viewfinder we’ve been using to look at fish and marine invertebrates. It was Philippa Ehrlich, a co-director of the film, who drew me towards the idea of fish living a full life. It’s a theory that is borne out with every new hour I spend observing the underwater wilderness just past the shore.

About the return of the larger reef fish of the Cape, Philippa was confident: “Here we have this incredibly intact habitat, in the great African kelp forest, which as far as kelp forests go is one of the healthiest in the world, and it’s just waiting to be repopulated with an abundance of reef fish that lived here 100 years ago. We can already see they’re coming back inside our marine protected areas, but they need all the help they can get. They’re fragile and their life histories are complex, and they’ve been pushed to the brink.”

It’s because of all of this that I choose to celebrate Marine Protected Areas Day, which helps raise awareness about the value of our marine ecosystems and the desperate need for us to do more to protect them. Marine protected areas are important for so many reasons, such as providing resilience against climate change, nurturing species previously thought to be extinct, and creating important economic benefits.

But for me, they’re also vital because they allow us to see the way our oceans should look, bringing us into a state of reverence for these aquatic wildernesses and their quiet mystery. Seeing places like these gives us something to strive for. And 5% is not enough. According to the IUCN and Australian Marine Sciences Association we should aim to give 30% of our waters full sanctuary protection if we are to staunch the loss of life inflicted by our current practices.

Months after I spoke to Philippa about reef fish, she sent me some pictures – vibrant images of Red Steenbras, Knifejaw and Red Roman swimming through shimmering kelp forests. She told me she’d found a tiny patch of hard-to-access kelp in the heart of a marine protected area no-take zone where these species were swimming. They were all juveniles, the first ambassadors of their kind to return to their ancestral waters.

I really want to be alive in a world where these fish grow to become giants. A world where it is us fishers who are restricted to small patches, while the rightful owners of the oceans can swim freely through cool, clean waters. DM/OBP

Opinionista • Christopher DZ Mason • 5 August 2021

How we consume seafood has become an implicitly political act. Our choices are our votes, defining our relationships to the ocean. It’s no longer enough to be motivated by half-price sushi. We need to work harder to know where our seafood comes from and whether or not eating that species can be considered viable.

South Africa’s inaugural Marine Protected Areas Day was on 1 August – a celebration of the 5% of our waters that are protected as sanctuaries for marine life, and a stark reminder that the other 95% of the oceans are not.

The scale makes it easy to lose sight of how the health of a single beach or reef can affect the whole system, or why small pockets of marine protected areas are so important. For this, one needs a zoomed-in view, which is something I’ve been afforded while spearfishing and free-diving along our coast. I’ve seen first-hand the difference that marine protected areas make to the way ocean ecosystems look and feel; how protected areas hold populations of big, mature fish while next door in legal fishing areas these species are far smaller and less abundant.

I’ve come to understand that marine protected areas give us a sense of what the baseline health of an ecosystem should look like, and I’ve also had to confront the difficult moral and ethical questions raised by my contribution to the denuding of these places. All of this has led me to believe that we have come to a point where we need to re-evaluate how we perceive ocean wilderness and consume the animals that come from it.

What’s also clear to me is that how we consume seafood has become an implicitly political act. Our choices are our votes, defining our relationships to the ocean in direct or indirect terms. It’s no longer enough to be motivated by half-price sushi. We need to work harder to know where our seafood comes from – not just the rough area, but the actual environment in which it was found, how it was caught, and whether eating that species can be considered viable.

For some people the answer is “don’t eat fish”. For me, the way forward is only eating what I catch. Of course, this is not possible for most. There are billions of people worldwide who rely on the oceans for food and jobs, who are often in poor coastal communities and don’t have the luxury of choice.

What we all share, however, is the opportunity for growing our relationship with the ocean through active interest and care. It brought me great joy to catch the first fish my daughter ate. She saw the whole animal first, a sleek and handsome yellowtail, and watched as I filleted and cooked it, understanding what it was she was eating when she took the first bite. It was the beginning of her relationship with a fish that had become for a time each summer our primary source of protein. What one feeds one’s family is an intimate and important thing. We’re each allowed to make that choice according to our beliefs and preferences, but regardless of what we choose – soy burgers, fresh fish or beef steaks – our choices have repercussions.

The deeper I pursued a direct relationship with the marine animals we ate, the more I began to see that the fish I was hunting, and the oceans in which they lived, were under far greater stress than I had first understood. For while the fast-growing and seasonally abundant pelagic species like Cape yellowtail proved to be exciting and sustainable green-listed quarry, the large reef fish of the Cape are already in great peril. Their life histories – being long-lived, slow growing and hyperterritorial – make them far more susceptible to fishing pressure.

One species that seemed to define the modern plight of the Cape reef fish with vivid and alarming complexity was the Red Roman. Striking and proud in bearing, it is one of the last of the large reef fish to still be seen with some regularity in the great African kelp forests of the Cape.

Traditionally, Red Romans have been highly sought after by line and spearfishermen alike. I remember going as a kid to the East London harbour with my Yiayia (Greek grandmother), who loved nothing more than an early trip to the docks to meet the fishermen on their return, and who prized Red Roman as an eating fish above all others.

These days the Red Roman is listed as near threatened on the IUCN Red List for Threatened Species and a quick Google search shows it’s still easy to buy them from, for example, Fish 4 Africa. It’s also legal for recreational fishermen to catch up to two a day with the correct permit.

But knowing this does not tell the whole story of the Red Roman or its importance as an indicator species in reef systems. Diving along the coast of False Bay, I would sometimes see Red Romans adding their custom splash of colour to the seabed. But they were few and far between compared with the numbers I saw in the “no-take” safe zones of the bay’s marine protected areas. When I started asking fishing friends about whether they thought we should be catching Red Romans, there was a mix of replies, ranging from “we recreational fisherman don’t make nearly as much of an impact as commercial fishermen” (which is true, with the disclaimer that recreational fisherman still make an impact), to “if it’s big and red, don’t shoot it!”

The scale makes it easy to lose sight of how the health of a single beach or reef can affect the whole system, or why small pockets of marine protected areas are so important. For this, one needs a zoomed-in view, which is something I’ve been afforded while spearfishing and free-diving along our coast. I’ve seen first-hand the difference that marine protected areas make to the way ocean ecosystems look and feel; how protected areas hold populations of big, mature fish while next door in legal fishing areas these species are far smaller and less abundant.

I’ve come to understand that marine protected areas give us a sense of what the baseline health of an ecosystem should look like, and I’ve also had to confront the difficult moral and ethical questions raised by my contribution to the denuding of these places. All of this has led me to believe that we have come to a point where we need to re-evaluate how we perceive ocean wilderness and consume the animals that come from it.

What’s also clear to me is that how we consume seafood has become an implicitly political act. Our choices are our votes, defining our relationships to the ocean in direct or indirect terms. It’s no longer enough to be motivated by half-price sushi. We need to work harder to know where our seafood comes from – not just the rough area, but the actual environment in which it was found, how it was caught, and whether eating that species can be considered viable.

For some people the answer is “don’t eat fish”. For me, the way forward is only eating what I catch. Of course, this is not possible for most. There are billions of people worldwide who rely on the oceans for food and jobs, who are often in poor coastal communities and don’t have the luxury of choice.

What we all share, however, is the opportunity for growing our relationship with the ocean through active interest and care. It brought me great joy to catch the first fish my daughter ate. She saw the whole animal first, a sleek and handsome yellowtail, and watched as I filleted and cooked it, understanding what it was she was eating when she took the first bite. It was the beginning of her relationship with a fish that had become for a time each summer our primary source of protein. What one feeds one’s family is an intimate and important thing. We’re each allowed to make that choice according to our beliefs and preferences, but regardless of what we choose – soy burgers, fresh fish or beef steaks – our choices have repercussions.

The scale makes it easy to lose sight of how the health of a single beach or reef can affect the whole system, or why small pockets of marine protected areas are so important. For this, one needs a zoomed-in view, which is something I’ve been afforded while spearfishing and free-diving along our coast. I’ve seen first-hand the difference that marine protected areas make to the way ocean ecosystems look and feel; how protected areas hold populations of big, mature fish while next door in legal fishing areas these species are far smaller and less abundant.

I’ve come to understand that marine protected areas give us a sense of what the baseline health of an ecosystem should look like, and I’ve also had to confront the difficult moral and ethical questions raised by my contribution to the denuding of these places. All of this has led me to believe that we have come to a point where we need to re-evaluate how we perceive ocean wilderness and consume the animals that come from it.

What’s also clear to me is that how we consume seafood has become an implicitly political act. Our choices are our votes, defining our relationships to the ocean in direct or indirect terms. It’s no longer enough to be motivated by half-price sushi. We need to work harder to know where our seafood comes from – not just the rough area, but the actual environment in which it was found, how it was caught, and whether eating that species can be considered viable.

For some people the answer is “don’t eat fish”. For me, the way forward is only eating what I catch. Of course, this is not possible for most. There are billions of people worldwide who rely on the oceans for food and jobs, who are often in poor coastal communities and don’t have the luxury of choice.

What we all share, however, is the opportunity for growing our relationship with the ocean through active interest and care. It brought me great joy to catch the first fish my daughter ate. She saw the whole animal first, a sleek and handsome yellowtail, and watched as I filleted and cooked it, understanding what it was she was eating when she took the first bite. It was the beginning of her relationship with a fish that had become for a time each summer our primary source of protein. What one feeds one’s family is an intimate and important thing. We’re each allowed to make that choice according to our beliefs and preferences, but regardless of what we choose – soy burgers, fresh fish or beef steaks – our choices have repercussions.

The scale makes it easy to lose sight of how the health of a single beach or reef can affect the whole system, or why small pockets of marine protected areas are so important. For this, one needs a zoomed-in view, which is something I’ve been afforded while spearfishing and free-diving along our coast. I’ve seen first-hand the difference that marine protected areas make to the way ocean ecosystems look and feel; how protected areas hold populations of big, mature fish while next door in legal fishing areas these species are far smaller and less abundant.

I’ve come to understand that marine protected areas give us a sense of what the baseline health of an ecosystem should look like, and I’ve also had to confront the difficult moral and ethical questions raised by my contribution to the denuding of these places. All of this has led me to believe that we have come to a point where we need to re-evaluate how we perceive ocean wilderness and consume the animals that come from it.

What’s also clear to me is that how we consume seafood has become an implicitly political act. Our choices are our votes, defining our relationships to the ocean in direct or indirect terms. It’s no longer enough to be motivated by half-price sushi. We need to work harder to know where our seafood comes from – not just the rough area, but the actual environment in which it was found, how it was caught, and whether eating that species can be considered viable.

For some people the answer is “don’t eat fish”. For me, the way forward is only eating what I catch. Of course, this is not possible for most. There are billions of people worldwide who rely on the oceans for food and jobs, who are often in poor coastal communities and don’t have the luxury of choice.

What we all share, however, is the opportunity for growing our relationship with the ocean through active interest and care. It brought me great joy to catch the first fish my daughter ate. She saw the whole animal first, a sleek and handsome yellowtail, and watched as I filleted and cooked it, understanding what it was she was eating when she took the first bite. It was the beginning of her relationship with a fish that had become for a time each summer our primary source of protein. What one feeds one’s family is an intimate and important thing. We’re each allowed to make that choice according to our beliefs and preferences, but regardless of what we choose – soy burgers, fresh fish or beef steaks – our choices have repercussions.

These days the Red Roman is listed as near threatened on the IUCN Red List for Threatened Species. (Photo: Steve Benjamin)

The latter came from Steve Benjamin, a good friend who taught me how to dive. Steve is both a marine biologist and a spearfisher and consciously walks the line that connects the two. It was from him that I started learning about the various fish species we encountered, and which ones I could target. Steve chooses to point his camera rather than his speargun at Red Roman, and has taken some of the most beautiful photos of the species in circulation today, and it was after talking to him about the plight of the Red Roman that I began to realise that it was perhaps because of it’s crimson conspicuousness that the species was so important. It was the last big red fish we were seeing on the reefs; the final warning light in a long line of now missing keystone species.

To understand what all this meant, I turned to another friend who was qualified to give me a real answer – filmmaker and conservation journalist Philippa Ehrlich. Philippa was writing about the urgent need to protect South African reef fish back in 2015 and it was her article that had helped me see the Red Roman in the context of an embattled line fishery. When I asked Philippa about the condition of the reef fish of False Bay now, she started with a story:

“A friend of mine, Lauren de Vos from Save Our Seas Foundation, had been telling me for a long time about these incredible reef fish species that live in South Africa and False Bay. But, I have dived in False Bay for most of my adult life and when I went through her list of fish I realised pretty quickly that the only one I was seeing was the Red Roman. So much of the original diversity had disappeared, which included animals like Red Steenbras, Red Stumpnose, Knifejaw, Jan Bruins, White Steenbras, Galjoen and Musselcracker. What was so shocking was that these were animals that have been gone for a long time. It’s not like they’ve only been fished out in the past 20 to 30 years.”

Indeed, the damage started many decades before, probably when large-scale commercial fishing became popular in the 1950s. By the turn of the century it was already clear to those looking at the data that we had a big problem with our reef fish (also known as linefish) populations. The 2013 edition of the Southern African Marine Linefish Species Profile puts it in plain English: “Following the declaration of an emergency in the South African linefishery in December 2000 and the recognition of the urgent need to rebuild many overexploited linefish stocks, implementation of the species-specific management plans eventually took place during the mid-2000s.”

It’s now clear that those management plans were not good enough and that there is a dire need for more marine protected areas, which act as havens that give fish populations the time and safety to recover. And, despite my despair in having to write this sentence of pure gloom, it’s only getting worse. The WWF Sassi website tells us there has been a dramatic increase in the number of fish taken out of the seas in recent decades, with many linefish species in South Africa being either dangerously overexploited or completely collapsed.

While our approach to harvesting marine life clearly needs careful overhauling, perhaps another part of the problem lies in the language we use to talk about “sea” food. When we think of “stocks” the word connotes a “quantity of something” that can be controlled and may fluctuate up or down. Like livestock, bred commercially, or commodities like whisky, wheat or chocolate, of which one can purchase more when “stocks” run low. Not so for the oceans and the fish in them.

We tend to forget that these are wild animals which we track and capture with ever-increasing technological sophistication in industrial fishing industries. Recreational fishing numbers are also growing, as is our skill in catching fish. When considering terrestrial and marine wilderness areas side by side, the only justifiable method of conservation is then complete protection for marine life within “no-take” sanctuary zones, like we do on land.

If we start thinking about them in the same light as our iconic game reserves, the conversation shifts. What makes a leopard’s life of greater value than a predatory reef fish like a Red Steenbras? The fish can live for up to 55 years, whereas the cat would typically only last 12, but yet the former seems doomed by its own deliciousness.

When asked about the importance of marine protected areas, Steve Benjamin replies in emphatic terms: “The oceans are under a massive amount of pressure, from fishing and industry, and they never get a break. Marine protected areas are like oases in a desert of human disturbance. We really need to treasure these last locations where ecosystems can remain functional and fish can live out their lives in a normal way.”

The idea of a fish living its life in a “normal” way stuck with me. The implication is that for the most part fish continually have their lives affected by humans, through fishing, pollution or habitat destruction. Thinking of fish as animals with a sovereign right to their own full experience of life is not something we’re used to.

But anyone who has seen the Oscar-winning documentary My Octopus Teacher is forced to re-evaluate the narrow and reductive “non-human” viewfinder we’ve been using to look at fish and marine invertebrates. It was Philippa Ehrlich, a co-director of the film, who drew me towards the idea of fish living a full life. It’s a theory that is borne out with every new hour I spend observing the underwater wilderness just past the shore.

About the return of the larger reef fish of the Cape, Philippa was confident: “Here we have this incredibly intact habitat, in the great African kelp forest, which as far as kelp forests go is one of the healthiest in the world, and it’s just waiting to be repopulated with an abundance of reef fish that lived here 100 years ago. We can already see they’re coming back inside our marine protected areas, but they need all the help they can get. They’re fragile and their life histories are complex, and they’ve been pushed to the brink.”

It’s because of all of this that I choose to celebrate Marine Protected Areas Day, which helps raise awareness about the value of our marine ecosystems and the desperate need for us to do more to protect them. Marine protected areas are important for so many reasons, such as providing resilience against climate change, nurturing species previously thought to be extinct, and creating important economic benefits.

But for me, they’re also vital because they allow us to see the way our oceans should look, bringing us into a state of reverence for these aquatic wildernesses and their quiet mystery. Seeing places like these gives us something to strive for. And 5% is not enough. According to the IUCN and Australian Marine Sciences Association we should aim to give 30% of our waters full sanctuary protection if we are to staunch the loss of life inflicted by our current practices.