The right hand does not know (or does not want to know) what the left hand is doing. The new minister of the DEA has no inclinations towards conservation it seems. Does she have any real idea of what she is doing? Certainly not of what she is supposed to do!!!

Lion Bones export Approved/Blood Lions

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67396

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Lion Bones export Approved/Blood Lions

Here we go again

The right hand does not know (or does not want to know) what the left hand is doing. The new minister of the DEA has no inclinations towards conservation it seems. Does she have any real idea of what she is doing? Certainly not of what she is supposed to do!!!

The right hand does not know (or does not want to know) what the left hand is doing. The new minister of the DEA has no inclinations towards conservation it seems. Does she have any real idea of what she is doing? Certainly not of what she is supposed to do!!!

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67396

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Lion Bones export Approved/Blood Lions

The big cat con: Inside Africa’s shocking battery farms for lions

BY SALLY WILLIAMS - 13 APRIL 2019 - THE TELEGRAPH

Some ranches are effectively battery farms CREDIT: FERGUS THOMAS

The growing appetite for ‘conservation holidays’ has shone a light on the dark – and poorly regulated – industry of lion farming, where felines are destined not to be ‘released into the wild’ – but to be shot by trophy hunters and their bones exported to Asia for use in traditional medicine.

Beth Jennings, 25, is mad about animals. After leaving school she worked for Dogs Trust, and then opted to spend a holiday looking after lion cubs rather than lying on a beach. Though it was called ‘volunteering’ she had to pay to do it: £1,500 for two weeks working at a game park in South Africa, plus £1,000 for flights and jabs. But she knew the wild lion population was in crisis, and this was her chance, according to the UK agency that sold it to her, to prepare orphaned cubs ‘for their eventual release into the wild’. She saved for more than a year, using her 21st-birthday money.

In South Africa, Jennings found about two dozen volunteers at the safari park, mainly girls in their early 20s, many from Scandinavia. But she was happy to be there. ‘Under the African sun I prepared for a hard day of work – bottle-feeding, cuddling, bathing and playing with lion cubs,’ she later wrote.

Yet by the second day she was worried. The lion cubs, it turned out, were not orphans. Staff took them away from their mothers when they were two weeks old so tourists could pet them and give them bottles.

‘The cubs make all these noises, which sound cute when you don’t know what’s happening. But then you realise it’s them calling out for their mothers,’ Jennings says.

Cub-petting, she explains, is lucrative – she estimates over 50 visitors a day at the safari park where she volunteered. When they are no longer cute, some progress to ‘walking with lions’ – where people pay for a close encounter with a big animal. When this becomes too risky, adult lions are moved into larger enclosures. And from there, Jennings discovered they are not, as staff claimed, ‘shipped to the Democratic Republic of Congo where they are all living happy lives’.

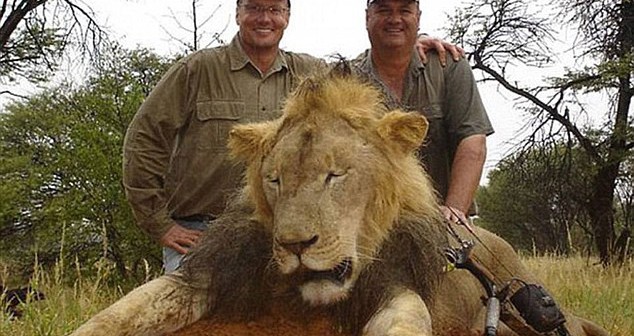

Instead they are more likely to be sold and transported elsewhere in South Africa to be shot by trophy hunters in so-called ‘canned hunting’ enclosures. Canned hunters can pay as little as £4,000 to shoot a female lion, less than half the cost of hunting a wild lion in Tanzania. Or the lions are killed for their skeletons. South Africa is the largest exporter of lion bones for use in traditional medicine in Vietnam, Thailand and Laos.

‘I was told so many lies,’ Jennings says. ‘By the agency selling the trip, by the park staff – they are pulling the wool over so many people’s eyes.’

Beth Jennings with a lion cub CREDIT: COURTESY OF BETH JENNINGS

Lions are an iconic species. It seems for all the people keen to cuddle them – bottle-feeding orphan cubs is always going to appeal to the vast wildlife-tourism market – there are an equal number keen to kill them. Royals like to pose with them, too – the Duke of Sussex was pictured tending a sedated lion in the wild not long ago, which is doubtless the kind of thing that volunteers think they will be doing.

In 1980, about 75,800 wild lions roamed the continent of Africa. Today it is estimated that fewer than 30,000 survive. In South Africa, there are barely 3,500 wild lions left. Behind the fences of the lion farms, however, the country’s captive lion population has grown. In 1999, there were about 1,000; today, some 8,000 are spread over more than 200 farms. (These numbers are estimates – experts agree there is a lack of transparency.) Lion farming and canned hunting are legal enterprises, and canned hunting has been worth millions to the economy. But such has been the outcry within South Africa and abroad about the practice of breeding lions expressly to be shot for sport, that the market has collapsed in the last few years – unintentionally fuelling the other equally controversial market for the country’s captive-bred lions, the bone trade.

South Africa’s lion farms are spread across the country, but many are concentrated in Free State, a large province south of Johannesburg. Some are private; others are open to the public. Even those that present themselves as a tourist attraction are often involved in breeding lions.

A cub on a South African ranch CREDIT: FERGUS THOMAS

‘South Africa is the only country really that breeds predators for commercial use,’ says Karen Trendler, head of wildlife trade and trafficking at the National Council of Societies for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (NSPCA). ‘From the time a cub is born and removed from the mother, it has five to seven years of quite a brutal cycle before it is slaughtered or hunted.’

The plight of southern Africa’s lions often makes the headlines. In 2015, the release of Blood Lions, an affecting documentary on predator breeding in South Africa, coincided with the death of Cecil, a wild lion who was killed by an American dentist and recreational big-game hunter just outside Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. Globally, there was outrage, and 42 airlines – Virgin Atlantic and British Airways among them – announced or reaffirmed bans of wildlife-trophy shipments on their flights. (Lion trophies are still allowed into the UK, however, despite a pledge by the government in 2015 that they would be banned unless the industry improved. A march supporting a ban is to take place in London today.)

But the biggest change was the US announcement in 2016 of a ban on the import of trophies from captive-bred lions in South Africa. Americans accounted for 80 per cent of the canned-hunting market. ‘It was a huge move forward,’ says Richard Peirce, the wildlife conservationist, film-maker and author of Cuddle Me, Kill Me, an exposé of canned hunting published last year. (The book was written with the assistance of James, a 34-year-old from Devon who went undercover as a volunteer on a lion farm.) ‘Canned hunting is nowhere near as big as it used to be.’ But as one source of income shrank, breeders went looking for new markets.

The export of lion bones to south-east Asia started in 2008, a consequence of a ban on breeding tigers for their bones, instigated at the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, in 2007. Tiger bone is used for traditional medicinal preparations. ‘Very few people can tell the difference between a lion bone and a tiger bone so it creates a convenient grey area,’ explains Michael ’t Sas-Rolfes, a doctoral researcher at the University of Oxford and an expert on the illegal wildlife trade. Suppliers to the traditional medicine markets in Vietnam, Thailand and Laos realised, he says, that hunting offered an alternative source of big-cat bones.

Lion farmers then discovered they could make almost twice as much – up to 50,000 rand (£2,600) – if the skeleton was ‘intact’, ie from a euthanised rather than hunted lion (whose skeletons are often damaged). Also, trophy lions are missing the most valuable body part: the skull, with its fangs. ‘Fangs are highly prized,’ ’t Sas-Rolfes explains, used for amulets and jewellery sold throughout south-east Asia. As a result, some farmers, hit by the trophy-import ban, switched to simply breeding lions for their skeletons. The business was worth about 16 million rand (£860,000) in 2017, according to the Captured in Africa Foundation. That year the South African government issued an export quota of 800 lion skeletons, which was used up within a month. A new quota of 1,500 skeletons per year was announced in July 2018; it was reduced back to 800 in December, partly in response to political pressure from campaigners and activists.

Canned hunting – in which lions are released into an enclosed space with no possibility of escape and then hunted – is legal in South Africa and is a multimillion-pound industry. CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES

I arrive at the ranch where James volunteered at around 11am. Fenced off, near the veranda of the ranch’s bar, three lions are sleeping on a platform. I pay less than 200 rand (£11) to go on a ‘game drive’. Nearby, there are pens holding a few dozen lions behind flimsy fences. The South African guide jumps down from the jeep and fills the water troughs. Fourteen or so young lions run alongside our vehicle. ‘They’re already sold,’ says the guide. ‘To a nature reserve. We’re only here to breed and protect.’

While James has moral qualms about the lion farming – ‘I don’t agree with it, but can understand it from their perspective’ – he was enraged by the cub-petting. The practice is easy revenue for the farmers, and allows the lioness to be swiftly reimpregnated. ‘Those little animals are there from the time the bar opens until the bar closes, in the heat, and the guys looking after them really don’t care.’

After lunch I pay less than 75 rand (£4) and am led into an enclosed yard with five lion cubs. The youngest is six weeks old, white and fluffy – I’m given her to hold. She is mewling, exhausted. In the wild, cubs sleep when they’re not eating. An employee says the ranch had over 100 visitors a day just before Christmas. ‘The mothers soon forget they’ve even had a cub,’ he tells me.

‘This is rubbish,’ says Hildegard Pirker, head of the Animal Welfare Department at Lionsrock Big Cat Sanctuary near Bethlehem, in Free State. There are 100 lions in her care at the sanctuary, run by the animal-rescue organisation Four Paws.

‘Lions have feelings. They mourn. They search. We know that from observing them here.’

South Africa is the largest exporter of lion bones. A large male skeleton will sell for 50,000 rand (£2,600) if it is ‘intact’, ie from a euthanised rather than hunted lion. CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES

We discuss the cub’s diet: cows’ milk, I was told. ‘Poor-quality,’ says Pirker. She inspects a picture of its distended belly on my phone. ‘This looks like malnutrition to me,’ she says.

I go to see another, far bigger lion farm in Free State that James also volunteered on. It’s huge: I count more than 15 enclosures. When I visit, there are around 200 lions, penned according to age – tiny cubs (removed at three weeks), juveniles, young adults and so on – rather than in prides, as they normally live. Billed as a tourist attraction, it’s clean, the lions are well fed, and staff tell us that release into the wild is their aim.

‘We are here to increase the number of these beautiful animals and rehabilitate them back into the wild,’ says an employee in his late teens. He appears convinced by his own claims, earnestly informing us that the lions are released in the north of the country. ‘Only the owner knows exactly where,’ he reports, ‘for the lions’ safety.’

‘Obviously these animals can’t go back into the wild,’ says Fiona Miles, country director, South Africa at Four Paws, ‘because where are these wild, open spaces? Even if they’re there, what about existing lions? Socialisation of lions is very sensitive. You could have fighting en masse [between released and established lions]. It would be impossible.’

Also, she adds, ‘If farmed lions were being rehabilitated, why do we not hear about it?’ There would be scientific papers, documentaries. ‘It would be an extraordinary achievement.’

James says staff at the large farm maintained the conservation story until the very end. Finally, another junior employee came clean. ‘We had a few beers, and eventually around midnight he said, “It’s obviously for the bone trade. You don’t have to be a genius to work it out.”’

Clayton Fletcher, a South African, knows the hunting and lion-farming business inside out. His late father was one of the first to breed lions in the 1960s and set up a hunting lodge in the Kalahari, several hundred miles west of Johannesburg, in 1980. Now renamed Tinashe safari lodge, it’s run by Fletcher and his wife. Fletcher used to breed lions for canned hunting – he had about 280 in 2007, according to reports. Now he buys them in.

‘Greenies’ – anti-hunting activists – ‘use raw emotion to target a public that is completely uneducated in the field of hunting,’ he says. He argues that hunting is a form of conservation: if you ban hunting, according to this logic, you are removing the economic value of wildlife. ‘The one thing that saves a lion is its value,’ Fletcher says.

He is also very sympathetic to the lion farmers in the wake of the American trophy ban: ‘Suddenly 80 per cent of the industry gets stopped in one day, what do you expect is going to happen? These people have to pay salaries, feed families, feed the lions.’

Besides, he adds, farming lions is the same as farming cattle. Karen Trendler disagrees, saying that at least cows are slaughtered for meat. ‘Lion bone is not benefiting South Africa. It’s being exported to other countries for their cultural uses.’

But her first priority is welfare. While there are rules for hunting lions, there are none effectively regulating their slaughter. ‘Now, because farmers want to keep the skull intact,’ Trendler says, ‘we have cruelty cases pending where the animals were shot through the eye or the ear with a low-calibre bullet so it didn’t damage the skull.’

Last May, a ‘lion abattoir’ was revealed, thanks to a whistle-blower, at Wag-’n-Bietjie farm near Bloemfontein in Free State, where over 50 lions had reportedly been shot. About 100 more were allegedly marked for slaughter. A case of animal cruelty was opened as two lions were held in a small crate for days without food or water, before being destroyed.

The word ‘abattoir’ is misleading, says Trendler. ‘It’s basically ad hoc. The guys will find a big warehouse – it’s even done in the open. They bring their cooking pots, bone processors, slaughterers. The lion is shot and the bone is processed. There is no control over it.’

Since the clampdown lion bones are often sold as tiger bones as few people know the difference.CREDIT: WILL BURGESS

The industry has made changes. The South African Predator Association (SAPA), which is in favour of what it calls ‘responsible’ breeding and hunting, disapproves of cub-petting, walking with lions, and ‘the practice of inviting young people from abroad to work on lion-cub-rearing stations’. However, according to Beth Jennings, ‘it’s still a problem’. Jennings now lives in Brighton, where she is a campaign manager at International Aid for the Protection & Welfare of Animals, as well as the founder of the blog Claws Out. ‘Fewer UK agencies are sending volunteers out, but it’s a global market; they aren’t going to be short of business any time soon.’

Sensing the mood, Safari Club International (SCI) – the world’s largest hunting club with 50,000 members – announced an opposition to ‘the hunting of African lions bred in captivity’ in February 2018. Despite its new policy of not allowing ‘operators to sell hunts for lions bred in captivity at the SCI Annual Hunters’ Convention’, at least 10 canned-hunting operators were present at the SCI convention in Reno, Nevada, in January. ‘SCI is investigating reports that suggest the policy may not have been followed,’ a spokesperson told me.

New hunting markets are opening up in countries with no trophy bans: Russia, UAE, China. The first-ever international hunting expo in China is to take place in Shanghai, in June. Four hundred lion trophies were sent to Eastern bloc countries from South Africa last year. And despite a national freeze on any lion-bone exports since the start of 2018, owing to legal action brought by the NSPCA, there is still ‘lion bone leaking out of the country’, says Trendler. Another loophole is the legal export of live animals. About 300 live lions (and tigers) have gone to south-east Asia from South Africa over the last two years. ‘That should be ringing all sorts of alarm bells,’ says Michele Pickover, director of EMS foundation, an animal- and human-welfare charity.

Four Paws, along with other animal charities, is calling for the closure of all lion-breeding farms. ‘No canned hunting, no bone trade, nothing,’ says Hildegard Pirker.

‘The whole industry contributes nothing to lion conservation,’ says Dr Mark Jones, head of policy at the Born Free Foundation. In fact, ‘the bone trade may present a risk to wild-lion conservation because the existence of a legal trade can incentivise the poaching of wild lions and other wild cats.

‘The industry needs to close down,’ he continues, but he notes the challenge that presents: ‘You’re talking about 8,000 to 12,000 sentient animals on these facilities. What does closure look like in terms of what happens to those animals? Their welfare must be respected.’

The South African government recently announced it is to appoint ‘a high-level panel’ to review policies on the management, breeding, hunting and trade of various animals including lions. ‘The panel will identify gaps, seek to understand and make recommendations,’ according to a press statement.

‘The government is in a difficult position,’ Trendler admits. ‘They have allowed this industry to grow. They have given out permits and legalised it.’ ‘The South African government has created a monster here,’ says Pickover, ‘and to get rid of that monster is really going to be a challenge.’

Read original article here:

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/0 ... rms-lions/

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67396

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Lion Bones export Approved/Blood Lions

Canned lion hunting campaign muzzled at World Travel Market

BY LOUISE DE WAAL - 15 APRIL 2019 - THE SOUTH AFRICAN

The "Blood Lions" presentation by Campaign Director, Nicola Gerrard, at WTM Africa in Cape Town last week was abruptly cut short after only five of a planned 20 minutes.

“"Blood Lions" has been welcomed and received huge support from leading travel operators during the WTM Africa show and we are shocked by the treatment of our organisation on a responsible tourism platform today,” Gerrard said.

Dr Harold Goodwin, the host of the Responsible Tourism Sessions, had interrupted Gerrard rather abruptly and rudely on several occasions, further restricting her time.

"Blood Lions" was once again a target at a South African tourism trade show after being ordered to remove their trailer banner at Indaba last year.

Winners of the Overall African Responsible Tourism Award in 2017, "Blood Lions" was invited to speak on their achievements. However, on Friday morning, a fourth speaker was included last minute and another speaker was allowed to go well over their allocated time, leaving the "Blood Lions" campaign with a mere five minutes to speak.

“I didn’t handle the situation well and apologise once more to the Blood Lions team and the audience in the venue for the way the session ended,” said Goodwin.

Blood Lion’s Ian Michler stated: “Our message leaves little room for obfuscation, and if this wasn’t another attempt to muzzle it, then it was an incredibly ham-fisted and unprofessional way to manage an international travel show.”

There are an estimated 8,000 predators held in captivity in small enclosures on 250-300 breeding facilities in SA. These animals are exploited at every phase of their lifecycle; captive lions have no conservation value despite the claims made by the breeders.

Over 140 leading international tourism operators have already signed the Blood Lions Born To Live Wild pledge, committing to stop supporting any exploitative wildlife tourism activities, such as cub petting and walking with lions, and the senseless killing of predators.

Read original article:

https://www.thesouthafrican.com/canned- ... de-market/

BY LOUISE DE WAAL - 15 APRIL 2019 - THE SOUTH AFRICAN

The "Blood Lions" presentation by Campaign Director, Nicola Gerrard, at WTM Africa in Cape Town last week was abruptly cut short after only five of a planned 20 minutes.

“"Blood Lions" has been welcomed and received huge support from leading travel operators during the WTM Africa show and we are shocked by the treatment of our organisation on a responsible tourism platform today,” Gerrard said.

Dr Harold Goodwin, the host of the Responsible Tourism Sessions, had interrupted Gerrard rather abruptly and rudely on several occasions, further restricting her time.

"Blood Lions" was once again a target at a South African tourism trade show after being ordered to remove their trailer banner at Indaba last year.

Winners of the Overall African Responsible Tourism Award in 2017, "Blood Lions" was invited to speak on their achievements. However, on Friday morning, a fourth speaker was included last minute and another speaker was allowed to go well over their allocated time, leaving the "Blood Lions" campaign with a mere five minutes to speak.

“I didn’t handle the situation well and apologise once more to the Blood Lions team and the audience in the venue for the way the session ended,” said Goodwin.

Blood Lion’s Ian Michler stated: “Our message leaves little room for obfuscation, and if this wasn’t another attempt to muzzle it, then it was an incredibly ham-fisted and unprofessional way to manage an international travel show.”

There are an estimated 8,000 predators held in captivity in small enclosures on 250-300 breeding facilities in SA. These animals are exploited at every phase of their lifecycle; captive lions have no conservation value despite the claims made by the breeders.

Over 140 leading international tourism operators have already signed the Blood Lions Born To Live Wild pledge, committing to stop supporting any exploitative wildlife tourism activities, such as cub petting and walking with lions, and the senseless killing of predators.

Read original article:

https://www.thesouthafrican.com/canned- ... de-market/

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67396

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Lion Bones export Approved/Blood Lions

Animal cruelty charges laid against lion farmer

BY DR LOUISE DE WAAL - 4 MAY 2019 - SA BREAKING NEWS

Photo credit: Conservation Action Trust

The NSPCA has laid criminal charges against Jan Steinman, a lion farmer in North West, for several contraventions of the Animal Protection Act after 108 lions, caracal, tigers and leopards were found in filthy and parasitic conditions.

Inspectors of the National Council of SPCAs (NSPCA) found 27 lions with severe mange, two lion cubs unable to walk, obese caracal unable to groom themselves, overcrowded and filthy enclosures, inadequate shelter, lack of water, and parasitic conditions.

Steinman, who owns the lion farm near Lichtenburg in the North West Province, is listed as a Council member of the South African Predator Association (SAPA).

“It is deplorable that any animal would be forced to live in such conditions, with such medical ailments. The fact that these are wild animals that are already living unnatural lives in confinement for the purposes of trade, just makes it more horrific”, said Senior Inspector Douglas Wolhuter (Manager NSPCA Wildlife Protection Unit).

SAPA claims that no welfare issues exist on member lion facilities. Mr Kirsten Nematandani (SAPA President) stressed to the Portfolio Committee of Environmental Affairs (PCEA) that “SAPA sets very high standards for [its]members”, at a Parliamentary Colloquium on Captive Lion Breeding in August 2018.

Nematandani assured the PCEA that they had “implemented SAPA’s Norms and Standards [N&S] for Breeding and Hunting to make sure everything is above board”.

The conditions found by NSPCA inspectors at Pienika Farm, where predators are kept for trophy hunting and the lion bone trade, are not only in breach of national legislation on animal welfare, but also several SAPA regulations, including those on animal welfare, husbandry of lions for hunting, minimum enclosure size, and the trade of lion products.

These N&S are binding to all SAPA members and failure to comply will supposedly lead to disciplinary action and possible expulsion of the offender, according to the SAPA website.

Some of the enclosures on Steinman’s farm housed in excess of 30 lionesses, giving them less than one quarter of the prescribed minimum space set by SAPA’s N&S.

“However, the very fact that SAPA have qualified their N&S with the word “undue” negates their N&S”, says Karen Trendler (Manager NSPCA Wildlife Trade & Trafficking Portfolio). “SAPA basically suggests that there are justifiable times for an animal to be hungry or thirsty, or suffer from fear, pain or disease, which is totally unacceptable in terms of animal welfare.”

In response to a public outcry in 2016 over emaciated lions on Mr Walter Slippers farm in Limpopo, SAPA publicly distanced themselves from Slippers, stating “if Mr Slippers had been a member and owner of a SAPA-accredited facility, we would have taken note of the unfolding tragedy and would have been in a position to act much earlier to prevent this lamentable state of affairs”.

However, that same year then SAPA Chairman Prof. Pieter Potgieter admitted in a Four Corners interview (Australia’s leading Investigative journalism programme) that some SAPA member facilities don’t comply with their “ethical code”. He also stated that out of the 200 SAPA members, he only managed to visit five farms.

It is unclear how SAPA enforces its N&S or how it deals with non-compliances of member facilities. Slipper’s non-membership was a convenient way out for SAPA in 2016. However, they must now be held to accountable to take appropriate action against Steinman.

The current animal cruelty case of a SAPA member facility in the NW once again demonstrations that the captive predator breeding industry continues to operate unchecked and unregulated, and animal welfare remains a huge concern.

There is no incentive to keep lions in a healthy condition, as all that is used are the skeletons for the lion bone trade. The Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) has set a legal annual export quota of 800 lion skeletons, normally used in the Traditional Chinese Medicine market or to be carved into jewellery.

Last month, DEA backtracked on the Parliamentary Resolution to introduce legislation to end the Captive Breeding of Lions in South Africa and proposed instead to allow the industry to continue with the introduction of regulation and appropriate legislation.

“On the 2nd May 2019, the NSPCA laid criminal charges against the owner of the farm at the SAPS Lichtenburg station based on several contraventions of the Animal Protection Act”, says Wolhuter.

Act now! Tell South African authorities to ban cruel captive breeding of lions for profit. Click here to sign the petition:

https://action.hsi.org/page/42430/actio ... -lion-farm

Read original article:

https://www.sabreakingnews.co.za/2019/0 ... on-farmer/

BY DR LOUISE DE WAAL - 4 MAY 2019 - SA BREAKING NEWS

Photo credit: Conservation Action Trust

The NSPCA has laid criminal charges against Jan Steinman, a lion farmer in North West, for several contraventions of the Animal Protection Act after 108 lions, caracal, tigers and leopards were found in filthy and parasitic conditions.

Inspectors of the National Council of SPCAs (NSPCA) found 27 lions with severe mange, two lion cubs unable to walk, obese caracal unable to groom themselves, overcrowded and filthy enclosures, inadequate shelter, lack of water, and parasitic conditions.

Steinman, who owns the lion farm near Lichtenburg in the North West Province, is listed as a Council member of the South African Predator Association (SAPA).

“It is deplorable that any animal would be forced to live in such conditions, with such medical ailments. The fact that these are wild animals that are already living unnatural lives in confinement for the purposes of trade, just makes it more horrific”, said Senior Inspector Douglas Wolhuter (Manager NSPCA Wildlife Protection Unit).

SAPA claims that no welfare issues exist on member lion facilities. Mr Kirsten Nematandani (SAPA President) stressed to the Portfolio Committee of Environmental Affairs (PCEA) that “SAPA sets very high standards for [its]members”, at a Parliamentary Colloquium on Captive Lion Breeding in August 2018.

Nematandani assured the PCEA that they had “implemented SAPA’s Norms and Standards [N&S] for Breeding and Hunting to make sure everything is above board”.

The conditions found by NSPCA inspectors at Pienika Farm, where predators are kept for trophy hunting and the lion bone trade, are not only in breach of national legislation on animal welfare, but also several SAPA regulations, including those on animal welfare, husbandry of lions for hunting, minimum enclosure size, and the trade of lion products.

These N&S are binding to all SAPA members and failure to comply will supposedly lead to disciplinary action and possible expulsion of the offender, according to the SAPA website.

Some of the enclosures on Steinman’s farm housed in excess of 30 lionesses, giving them less than one quarter of the prescribed minimum space set by SAPA’s N&S.

“However, the very fact that SAPA have qualified their N&S with the word “undue” negates their N&S”, says Karen Trendler (Manager NSPCA Wildlife Trade & Trafficking Portfolio). “SAPA basically suggests that there are justifiable times for an animal to be hungry or thirsty, or suffer from fear, pain or disease, which is totally unacceptable in terms of animal welfare.”

In response to a public outcry in 2016 over emaciated lions on Mr Walter Slippers farm in Limpopo, SAPA publicly distanced themselves from Slippers, stating “if Mr Slippers had been a member and owner of a SAPA-accredited facility, we would have taken note of the unfolding tragedy and would have been in a position to act much earlier to prevent this lamentable state of affairs”.

However, that same year then SAPA Chairman Prof. Pieter Potgieter admitted in a Four Corners interview (Australia’s leading Investigative journalism programme) that some SAPA member facilities don’t comply with their “ethical code”. He also stated that out of the 200 SAPA members, he only managed to visit five farms.

It is unclear how SAPA enforces its N&S or how it deals with non-compliances of member facilities. Slipper’s non-membership was a convenient way out for SAPA in 2016. However, they must now be held to accountable to take appropriate action against Steinman.

The current animal cruelty case of a SAPA member facility in the NW once again demonstrations that the captive predator breeding industry continues to operate unchecked and unregulated, and animal welfare remains a huge concern.

There is no incentive to keep lions in a healthy condition, as all that is used are the skeletons for the lion bone trade. The Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) has set a legal annual export quota of 800 lion skeletons, normally used in the Traditional Chinese Medicine market or to be carved into jewellery.

Last month, DEA backtracked on the Parliamentary Resolution to introduce legislation to end the Captive Breeding of Lions in South Africa and proposed instead to allow the industry to continue with the introduction of regulation and appropriate legislation.

“On the 2nd May 2019, the NSPCA laid criminal charges against the owner of the farm at the SAPS Lichtenburg station based on several contraventions of the Animal Protection Act”, says Wolhuter.

Act now! Tell South African authorities to ban cruel captive breeding of lions for profit. Click here to sign the petition:

https://action.hsi.org/page/42430/actio ... -lion-farm

Read original article:

https://www.sabreakingnews.co.za/2019/0 ... on-farmer/

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67396

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Lion Bones export Approved/Blood Lions

All the lion farmers got a "go ahead" from the authorities. Obviously, they have not done a proper check up on any of them or only of a few, because this one would certainly not have got a permit from the ministry....I hope

out of the 200 SAPA members, he only managed to visit five farms. Are they kidding? and all 200 got the permit renewed

Are they kidding? and all 200 got the permit renewed

out of the 200 SAPA members, he only managed to visit five farms.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5862

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

Re: Lion Bones export Approved/Blood Lions

Some interesting details and conclusions in this article, worth reading  the entire papaer

the entire papaer

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/artic ... ne.0217409

Born captive: A survey of the lion breeding, keeping and hunting industries in South Africa

Vivienne L. Williams , Michael J. ‘t Sas-Rolfes

Published: May 28, 2019

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/artic ... ne.0217409

Born captive: A survey of the lion breeding, keeping and hunting industries in South Africa

Vivienne L. Williams , Michael J. ‘t Sas-Rolfes

Published: May 28, 2019

Abstract

Commercial captive breeding and trade in body parts of threatened wild carnivores is an issue of significant concern to conservation scientists and policy-makers. Following a 2016 decision by Parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, South Africa must establish an annual export quota for lion skeletons from captive sources, such that threats to wild lions are mitigated. As input to the quota-setting process, South Africa’s Scientific Authority initiated interdisciplinary collaborative research on the captive lion industry and its potential links to wild lion conservation. A National Captive Lion Survey was conducted as one of the inputs to this research; the survey was launched in August 2017 and completed in May 2018. The structured semi-quantitative questionnaire elicited 117 usable responses, representing a substantial proportion of the industry. The survey results clearly illustrate the impact of a USA suspension on trophy imports from captive-bred South African lions, which affected 82% of respondents and economically destabilised the industry. Respondents are adapting in various ways, with many euthanizing lions and becoming increasingly reliant on income from skeleton export sales. With rising consumer demand for lion body parts, notably skulls, the export quota presents a further challenge to the industry, regulators and conservationists alike, with 52% of respondents indicating they would adapt by seeking ‘alternative markets’ for lion bones if the export quota allocation restricted their business. Recognizing that trade policy toward large carnivores represents a ‘wicked problem’, we anticipate that these results will inform future deliberations, which must nonetheless also be informed by challenging inclusive engagements with all relevant stakeholders.

Introduction

The African lion is currently the only big cat of the genus Panthera for which international commercial trade is legal under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) [1]. In response to emerging market demands for lion products, including viewing tourism, cub petting, trophy hunts and body parts, entrepreneurs in South Africa have developed a substantial commercial captive lion breeding industry, reaching a scale similar to that of captive tiger breeding operations in China [2,3]. As with China’s so-called ‘tiger farms’, the role of such commercial breeding operations is debated, with critics arguing that their presence has no conservation value [4] and, at least in the case of tigers, may even constitute a threat to wild populations [5]. However, the exact relationship between captive and wild lion populations remains evidentially unclear, and it is also plausible that the former may provide a buffer effect against over-exploitation of the latter [6]. This relationship warrants further investigation, especially given increasingly vocal public opposition to commercial captive lion breeding and some recent consequential trade policy shifts.

At the 17th CITES Conference of the Parties (CoP17) in 2016, debates on the trade in lion body parts intensified when consensus could not be reached on a proposal by nine predominantly western African countries to transfer all African populations of Panthera leo (African Lion) from Appendix II to Appendix I of CITES [1,7–9]. Several southern African countries in particular rejected the proposal [1,7–9]. Instead, through negotiations within a working group, a compromise to retain P. leo on Appendix II was agreed with the following annotation: A zero annual export quota is established for specimens of bones, bone pieces, bone products, claws, skeletons, skulls and teeth removed from the wild and traded for commercial purposes. Annual export quotas for trade in bones, bone pieces, bone products, claws, skeletons, skulls and teeth for commercial purposes, derived from captive breeding operations in South Africa, will be established and communicated annually to the CITES Secretariat [10].

In accordance with the annotation, South Africa must establish an annual export quota for captive-origin lion body parts. The South African CITES Scientific Authority, based at the South African Biodiversity Institute (SANBI), advises the South African Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) on the proposed size of this quota (although the Ministry of Environmental Affairs makes the ultimate decision). In South Africa, conservation regulation is a competence shared between the national government and nine provincial agencies, the latter of which may have significantly varying laws and consequent lion management practices. Accordingly, the Scientific Authority draws upon these provincial agencies for input.

In 2017, the Scientific Authority initiated a programme of interdisciplinary, collaborative, scientific research with university institution affiliates (including ourselves) to obtain further information on lions bred and maintained in captivity (hereafter referred to as ‘the captive lion industry’), legal and illegal trade, and consequences of trade for wild lions; this information is assimilated and used in policy recommendations to the DEA. As part of this research, we initiated the ‘National Captive Lion Survey’ of privately-owned properties with lions held captive for various core purposes, viz.: breeding, hunting, and ‘keeping’ (i.e. the retention and rearing of lions for personal pleasure, display, rehabilitation, security, and potential future sales of live animals and body parts).

The survey was run from August 2017 to May 2018 and was intended to establish baseline information for understanding the essential factors and dynamics at the interface between captive lions and wild lion conservation. The stated core aims were to: (i) understand the captive lion breeding, keeping, and hunting industries, and the trade in lions (live animals, bones and other products); (ii) investigate the trade in captive-produced lion skeletons under the newly implemented quota system; (iii) gain an understanding of the consequences of trade bans/suspensions on imports of captive-origin trophies on both the captive lion industry and wild lions; and (iv) strengthen the evidence base for the annual review of the lion skeleton export quota. Given the variability of purpose and practice within the captive lion industry, not all the aims were relatable to all responding facilities (especially those that do not sell live lions and products or allow hunting on the premises). However, given the ability of facilities to exchange live lion stocks, we sought to gather as much information as possible across the entire industry, including relevant differences in practice between provincial jurisdictions that may have arisen as a consequence of their regulatory disparities.

Our approach was grounded in two key propositions. The first is that South Africa’s captive lion industry constitutes part of a complex adaptive social-ecological system, which includes and potentially affects in situ populations of lions and other large felids, via trade and other mechanisms that remain poorly understood [11,12]. Second is that the most appropriate way for the Scientific Authority to address such uncertainty is by employing principles of adaptive management, informed by an ongoing process of scientific research [13]. We further postulate that, in respect of commercial activities related to lions, both legal and illegal actors are substantially motivated by economic incentives. This is consistent with past similar analyses related to tigers [14] and highlights the importance of establishing indicative economic data such as trends in sales volumes, stock management and market prices, as these will drive future adaptive market activity.

Williams et al [1,2,15] questioned whether measures implemented between 1993 and 2007 to curb the Asia-driven tiger parts trade provoked the start of South Africa’s lion bone trade in 2008 (Fig 1), and hence whether well-meaning policy interventions intended to protect species can create economic incentives that perversely influence trade dynamics and lead to unintended consequences elsewhere. In conducting the National Captive Lion Survey, we similarly aimed to explore the impacts that trade bans, such as the United States of America’s (USA) suspension on imports of captive-origin lion trophies from early 2016, might have on the hunting industry and accordingly on captive lion breeding. Since American hunters comprise >50% of South Africa’s foreign hunting clients (this survey, [1,2]), and they imported >50% of the lion trophies originating from captive-born lions [16], we hypothesized that, subsequent to the trade suspension, the market for lion hunts would decline significantly and consequently induce some hunting and breeding facilities with a surplus of captive lions to reduce their stock numbers by euthanasia and sell these skeletons to Asia to recoup their loss of earnings [1]. The results of our survey confirmed this prediction.

Whereas an earlier survey of the captive lion industry investigated its economic significance [17], we sought more specific evidence on industry participant reactions to inter-provincial regulatory variability, changing policies, and changing market conditions, and how these might ultimately impact upon lion breeding, trade, and conservation. Following confirmation that disruption to the hunting market has significantly affected the industry, we questioned what strategies industry participants would employ in response to consequent losses of income. We also sought insight into the added impacts of the instituted skeleton export quota, which in 2017 amounted to an effective contraction to less than half the number actually exported in 2016 (Fig 1). The results of the survey are intended to inform future policy deliberations rather than be prescriptive, although they do highlight risk areas that warrant attention if threats to wild lions are to be adequately mitigated.

Discussion

The survey provided useful baseline information on South Africa’s captive lion industry. The sample limitations of the first round (in 2017) were overcome after the follow-up round (in 2018), although receiving responses in two separate years created some challenges for collation and interpretation of the data. Mindful of these, we attempted to account for any resultant discrepancies in our analyses. Given that this industry is currently subject to significant activist pressure, we had to overcome the reluctance of participants to divulge data and therefore potentially sacrifice some elements of rigour. Furthermore, much of the data and analysis thereof falls within the realm of social science, in which certain trade-offs of this nature are inevitable. Nonetheless, the final sample was sufficiently large and with enough consistency of data and trends for us to feel confident in the integrity of the findings.

The results provide not only a substantial geographic overview (by provincial jurisdiction) of the industry, but the time series data provide insight into the economic impacts of a significant policy intervention (the USA lion trophy import suspension), as well as consequent implications for conservation. The qualitative elements of certain responses provide additional insight into industry participants’ motivations and possible future actions. This information is likely to be of interest to scholars from diverse disciplines, broadly including law, economics, and conservation science; and, more narrowly including industrial organisation theory, economic geography, economic sociology, environmental regulation, trade regulation, and decision theory.

The results indicate that the captive lion industry is in an economically unstable state, having been significantly affected by the 2016 USA lion trophy import suspension and implementation of the skeleton export quota in 2017. The USA suspension has also changed industry perceptions and behaviour in respect of the export market for other lion body parts. Whereas industry participants viewed bone exports to Asia as an optional supplementary by-product market from the years 2008 to 2015, their interest in this market grew immediately following the suspension; this growing interest is also likely driven by increasing market prices for skeletons over the last five years. Furthermore, evidence suggests that 2016 heralded a new era for the trade in body parts once large volumes of intact skeletons from euthanized lions entered the export market. The price data reflect a significant and rising price premium for skeletons with skulls, reaching price levels for females that are now close to their live sales prices. It therefore appears that the USA intervention has inadvertently spawned a new lucrative direct export market for whole skeletons of euthanized lions from breeding farms.

Industry participants are adapting to the current trade restrictions in different ways. Those involved with hunting are seeking new markets and this sector may grow again, albeit at slower rates. However, if there is no substantial change in USA policy, or if there are further EU lion trophy import restrictions, breeders will feel pressured to explore further options to mitigate expected financial losses. Different breeders will continue to respond in various ways, which are not easy to predict. Some are likely to scale down significantly, if not disinvest from lion breeding altogether. At least some of these will euthanize their animals and attempt to recover costs through sale of skeletons. Most breeders appear hopeful or expectant of at least some ongoing access to an export market for lion body parts.

There are now three apparent types of potential lion skeleton exporters: (i) the hunting industry participants who seek to continue the traditional by-product trade, (ii) down-scaling breeders who are euthanizing their animals and attempting to recoup financial losses, and (iii) a new potential category of commercial breeders who might deliberately continue to act as bespoke intact skeleton suppliers. The extent to which the third category is capable of persisting as a viable stand-alone business sector remains to be seen; nevertheless, all three sources must compete for allocations of any future skeleton export quotas. The South African government must evaluate its quota-setting policies against this backdrop of both increasing economic pressures for all industry participants to become sellers and evident increasing demand from Asian buyers (reflected by rising prices, especially for skulls).

The fact that a large proportion of respondents have stated that they will seek ‘other markets’ for lion bones and other body parts signals the potential for a parallel illegal market to develop if quotas are viewed by industry participants as excessively restrictive. South Africa experienced a similar situation with rhino horn trade, whereby increased restrictions were contested by market participants, sparking a significant wave of illegal activity [26]. Should any South African captive lion industry participants develop closer links with organized criminal enterprises, the effects could be irreversible and result in greater and more widespread threats of focused commercial-scale poaching of wild felids. Well-informed existing legal exporters of lion skeletons (who are not owners of lion breeding or hunting facilities) share these concerns and the survey responses (indicating the belief that the captive lion industry acts as a buffer to protect wild lion populations from overexploitation) support this further.

Aside from considering a possible buffer effect of legal body part exports, questions remain on the conservation role of captive lion breeding for hunting. The sizes of the lion hunting areas suggest there may be indirect benefits to biodiversity conservation, i.e. through provision of economic support to maintain the natural integrity of these privately-owned ecosystems, which might otherwise be lost through conversion to other forms of land use such as agricultural monocropping. We recommend further research on this aspect, especially given the evident impact of the USA lion trophy import suspension. This impact is reflected by falling sales of lion hunts and numbers of live lions sold, consequent falling income levels and market prices of live lions, widespread operational down-scaling, losses in human employment, and loss of hunting clientele (for other species in addition to lions). These impacts could ultimately lead to land conversion and consequent biodiversity loss. Possible impacts on hunting of wild lions elsewhere remains a subject of some conjecture and also warrants further research.

Given an objective of informing future trade policy decisions, the results indicate areas that warrant ongoing monitoring and investigation. These include: (i) the total number of captive lions, (ii) trends in the market prices paid for live animals and skeletons (including the premium paid for skulls), (iii) the prevalence of lion poisonings and poaching on private property, (iv) how facilities continue to adapt to trade bans/restrictions and/or a quota, and (v) the changes/losses in earning across all sectors of the captive lion industry. Such information can guide any decisions made under an adaptive management approach aimed at minimising the risk of adversely affecting wild lion populations. In this regard, one of the most useful aspects to understand would be the price elasticity of demand for lion body parts. Monitoring market price responses to changes in quantity supplied would provide useful indicative evidence of this, suggesting another appropriate use for carefully considered quota adjustments. However, policy-makers should take care to avoid price shocks—i.e. sudden upward spikes in market prices that would boost incentives for poaching and illegal trading activity, with potential adverse consequences for wild lions.

Critics of the captive lion breeding industry raise animal welfare and ethical issues in addition to specific conservation concerns, whereas proponents of the industry argue that it provides both broader conservation and economic benefits to society, even if the former are somewhat indirect and not immediately obvious. These contrasting views highlight some inherent trade-offs in addressing multiple, potentially conflicting social policy objectives in the context of a complex adaptive system with global reach. In this regard, policy toward the captive lion industry may be viewed as a ‘wicked problem’ [27], for which there is no universally optimal solution, and one for which stakeholders may even disagree over the definition of the problem “if they are personally invested in pursuing a particular solution” [28]. This represents a serious challenge to those seeking to determine appropriate management actions by way of collaboration between all stakeholders. Current broader research on this topic considers techniques to gain a deeper shared understanding of the areas of risk and uncertainty and how to address them, given the substantial differences in values evident among stakeholders. Such techniques include participatory scenario planning and ethical argument analysis [29], both of which may provide additional guidance on these complex policy decisions. We anticipate that the results we have presented here will illuminate and inform ongoing deliberations, but they are certainly not the final word on them.

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67396

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Lion Bones export Approved/Blood Lions

Not much that has not already been published apart from the influence on other sectors if a change happens. I would never have thought that the USA suspension on trophy imports from captive-bred South African lions has had such a big impact. Obviously, the number of trophy hunters is much bigger than I imagined.

Interesting read raising loads of problems: Economic, ethical and political.

Where have you found the above, Klippie?

Interesting read raising loads of problems: Economic, ethical and political.

Where have you found the above, Klippie?

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5862

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact: