Miners are ripping up the West Coast

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 66797

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Miners are ripping up the West Coast

Every time there is a permit from some or other state institution at stake, the decisions of the public officials seem to have been taken with eyes closed and brains asleep  and the result is a court case that costs time and money....but not that of the the sleeping officials

and the result is a court case that costs time and money....but not that of the the sleeping officials

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 66797

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Miners are ripping up the West Coast

DMRE rejects West Coast prospecting bid over lack of environmental impact planning

Old rustic huts are still scattered over the Karoetjies Kop 150 farm’ coastal area. They are used by surfers and other travellers to the West Coast for shelter. (Photo: Ant Fox)

By John Yeld | 19 Sep 2023

The department's refusal of an environmental application for prospecting signals a shift towards more rigorous scrutiny of mining and prospecting applications to protect the region's pristine environment.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Environmental authorisation for a prospecting application to search for heavy minerals, kaolin and gemstones in one of the few relatively pristine areas of the West Coast has been refused by the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE).

This unexpected decision has surprised and pleased West Coast environmental activists. They say they hope that it “signals a shift” by the DMRE towards more rigorous scrutiny of the environmental and other legislative requirements for mining and prospecting applications.

However, the prospecting company, Limpopo-based Nekwana Trading Enterprise (Pty) Ltd, is questioning the DMRE’s decision and the adjudication process.

Director Nekwana Seroka told GroundUp that the company had not received any directive from the department and the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act process had not been followed.

He also wondered whether unnamed “external forces” had played any role in the decision, but he did not elaborate.

The prospecting application — one of two targeting the same farm, Karoetjies Kop 150, on the border between the Western Cape and Northern Cape provinces — was submitted in April last year.

Nekwana planned to prospect for sillimanite, monazite, manganese ore, leucoxene, diamonds, kaolin and garnets.

In its documentation, the company said prospecting work would include drilling 12 boreholes to test target areas identified through mapping, and geophysical and geochemical surveys. A further 10 or so boreholes might be drilled, depending on initial results.

In May this year, Nekwana’s environmental consultants TPR Mining Resources (Pty) Ltd submitted a final Basic Assessment Report (BAR) and proposed Environmental Management Programme (EMP) for the prospecting operations, as legally required.

A Basic Assessment Report is a low-level of environmental assessment that applies to small-scale activities, the impacts of which are generally known and can be easily managed. While less than a full EIA (Environmental Impact Assessment), a BAR still requires public notice and participation; consideration of the potential environmental impacts; assessment of possible mitigation measures; and an assessment of whether there are any significant issues or impacts that might require further investigation.

Refusal

In the DMRE’s letter of decision, signed 31 August by Western Cape Regional Manager Mineral Regulation, the department said it was not satisfied that the BAR and EMP for Nekwana’s application complied sufficiently with the National Environmental Management Act (Nema) and associated EIA Regulations.

Pointing out that it had granted three extensions to the deadline for Nekwana to submit a BAR, the department said it had reviewed the report and found that several significant issues had not been sufficiently addressed.

The layout plan provided did not show the exact position of the prospecting drill holes, access roads to the sites, and other required infrastructure. “It is therefore impossible to describe the environment, [and] assess and mitigate the impacts of the proposed prospecting activities and access tracks to the site if the exact location of the proposed drill holes and access tracks are not known.”

Also, the specialist terrestrial ecology report had only provided background information on ecosystems, and on-site survey results had not provided enough information to delineate ecologically sensitive “no-go” areas.

A further point was that Heritage Western Cape had informed the applicant that an adequate Heritage Impact Assessment had to be submitted, with specific reference to potential archaeological and palaeontological impacts. But only a desktop Palaeontological Impact Study had been included in the final BAR.

There was no proof of consultation with relevant conservation bodies, IAAPs (interested and affected parties) or the local municipality, the refusal letter stated.

“The Department wishes to advise that due consideration shall at all times be given to the general objectives of integrated environmental management laid down in Chapter 5 of Nema, as well as the requirements of the EIA Regulations whenever the potential detrimental impacts to the environment are addressed. The application is accordingly refused.”

The refusal is subject to a possible appeal. Seroka did not indicate to GroundUp whether the company intends to appeal.

Decision welcomed

The DMRE decision was welcomed by Protect the West Coast, a non-profit collective including scientists, journalists, activists, legal and media experts and surfers, who aim to ensure that West Coast mining is conducted “with the correct and proper oversight in accordance with fundamental principles of the law”.

The group’s managing director Mike Schlebach said the decision vindicated the work they were doing in holding mining companies to account.

“[This is] a sure sign that the DMRE is sitting up and taking stock of its mandate to ensure mining is done in compliance with appropriate regulations and that mining permits can’t just be handed out to any company that applies for one,” he said.

Schlebach suggested that this decision and the recent settlement agreement reached with diamond miner Trans Hex represented “a turning point … a gradual mindset change from fossil fuel-based, single use mining to nature-based solutions that promote tourism, aquaculture, small scale fisheries, and the management of key water and agricultural resources.

“Illegal mining and the well-being of communities and the environment are just not compatible,” he said. DM

First published by GroundUp.

Old rustic huts are still scattered over the Karoetjies Kop 150 farm’ coastal area. They are used by surfers and other travellers to the West Coast for shelter. (Photo: Ant Fox)

By John Yeld | 19 Sep 2023

The department's refusal of an environmental application for prospecting signals a shift towards more rigorous scrutiny of mining and prospecting applications to protect the region's pristine environment.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Environmental authorisation for a prospecting application to search for heavy minerals, kaolin and gemstones in one of the few relatively pristine areas of the West Coast has been refused by the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE).

This unexpected decision has surprised and pleased West Coast environmental activists. They say they hope that it “signals a shift” by the DMRE towards more rigorous scrutiny of the environmental and other legislative requirements for mining and prospecting applications.

However, the prospecting company, Limpopo-based Nekwana Trading Enterprise (Pty) Ltd, is questioning the DMRE’s decision and the adjudication process.

Director Nekwana Seroka told GroundUp that the company had not received any directive from the department and the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act process had not been followed.

He also wondered whether unnamed “external forces” had played any role in the decision, but he did not elaborate.

The prospecting application — one of two targeting the same farm, Karoetjies Kop 150, on the border between the Western Cape and Northern Cape provinces — was submitted in April last year.

Nekwana planned to prospect for sillimanite, monazite, manganese ore, leucoxene, diamonds, kaolin and garnets.

In its documentation, the company said prospecting work would include drilling 12 boreholes to test target areas identified through mapping, and geophysical and geochemical surveys. A further 10 or so boreholes might be drilled, depending on initial results.

In May this year, Nekwana’s environmental consultants TPR Mining Resources (Pty) Ltd submitted a final Basic Assessment Report (BAR) and proposed Environmental Management Programme (EMP) for the prospecting operations, as legally required.

A Basic Assessment Report is a low-level of environmental assessment that applies to small-scale activities, the impacts of which are generally known and can be easily managed. While less than a full EIA (Environmental Impact Assessment), a BAR still requires public notice and participation; consideration of the potential environmental impacts; assessment of possible mitigation measures; and an assessment of whether there are any significant issues or impacts that might require further investigation.

Refusal

In the DMRE’s letter of decision, signed 31 August by Western Cape Regional Manager Mineral Regulation, the department said it was not satisfied that the BAR and EMP for Nekwana’s application complied sufficiently with the National Environmental Management Act (Nema) and associated EIA Regulations.

Pointing out that it had granted three extensions to the deadline for Nekwana to submit a BAR, the department said it had reviewed the report and found that several significant issues had not been sufficiently addressed.

The layout plan provided did not show the exact position of the prospecting drill holes, access roads to the sites, and other required infrastructure. “It is therefore impossible to describe the environment, [and] assess and mitigate the impacts of the proposed prospecting activities and access tracks to the site if the exact location of the proposed drill holes and access tracks are not known.”

Also, the specialist terrestrial ecology report had only provided background information on ecosystems, and on-site survey results had not provided enough information to delineate ecologically sensitive “no-go” areas.

A further point was that Heritage Western Cape had informed the applicant that an adequate Heritage Impact Assessment had to be submitted, with specific reference to potential archaeological and palaeontological impacts. But only a desktop Palaeontological Impact Study had been included in the final BAR.

There was no proof of consultation with relevant conservation bodies, IAAPs (interested and affected parties) or the local municipality, the refusal letter stated.

“The Department wishes to advise that due consideration shall at all times be given to the general objectives of integrated environmental management laid down in Chapter 5 of Nema, as well as the requirements of the EIA Regulations whenever the potential detrimental impacts to the environment are addressed. The application is accordingly refused.”

The refusal is subject to a possible appeal. Seroka did not indicate to GroundUp whether the company intends to appeal.

Decision welcomed

The DMRE decision was welcomed by Protect the West Coast, a non-profit collective including scientists, journalists, activists, legal and media experts and surfers, who aim to ensure that West Coast mining is conducted “with the correct and proper oversight in accordance with fundamental principles of the law”.

The group’s managing director Mike Schlebach said the decision vindicated the work they were doing in holding mining companies to account.

“[This is] a sure sign that the DMRE is sitting up and taking stock of its mandate to ensure mining is done in compliance with appropriate regulations and that mining permits can’t just be handed out to any company that applies for one,” he said.

Schlebach suggested that this decision and the recent settlement agreement reached with diamond miner Trans Hex represented “a turning point … a gradual mindset change from fossil fuel-based, single use mining to nature-based solutions that promote tourism, aquaculture, small scale fisheries, and the management of key water and agricultural resources.

“Illegal mining and the well-being of communities and the environment are just not compatible,” he said. DM

First published by GroundUp.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 66797

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Miners are ripping up the West Coast

West Coast mineral extraction raking in billions of rands while communities endure rising poverty

Sand mining in Matzikama, the northernmost part of the Western Cape. (Photo: Transnational Institute)

By Kristin Engel - 07 May 2024

Mining has existed on the West Coast for over 100 years. A new report looks at what these valuable mineral sands are and how surrounding communities still suffer extreme poverty, unemployment and food insecurity. At the heart of this narrative are the heavy minerals —- zircon, ilmenite, and rutile — concealed within the grains of sand.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Originally from Papendorp and now residing in Doringbaai, chairperson of Coastal Links Western Cape Andre Cloete has been a fisher for over 20 years. He said that mining has left destruction in his community and all along the West Coast with no rehabilitation when mining companies finish their activity. He says it’s not just the physical environment but also the community that is suffering.

“One of the main things is that they [mining companies] leave the physical environment in a state and they don’t invest in the communities. They provide jobs only for a certain time, a few months, it’s all contractual and not permanent… People don’t thrive or prosper from these jobs while they [mining companies] on the other hand reap the benefits. You can see it.

“For the past five years, if we look at snoek, you don’t get as much as you normally do because of all these explorations happening now… Even with crayfish in Elands Bay, it’s crayfish season now and there’s no lobster during the day. We have to work at night because you don’t get anything during the day… Normally you get tons of fish and lobster in Elands Bay, now it’s only during the night because there’s less disturbance during the night,” Cloete said.

Cloete said there is no medical clinic in Papendorp, with community members having to travel to either Lutzville or Dorongbaai for treatment, yet mining companies were making billions from the minerals extracted from these communities.

This is the story of one of the contributors of a report, showing the impact of the historical reaping of minerals from poverty-stricken communities on the West Coast for billions over time.

“The Sand Worth Billions: How mining companies are reshaping South Africa’s West Coast” was authored by Carsten Pedersen from the Transnational Institute. The initial research and work of the report was conducted by Masifundise Development Trust, Cloete, as well as a few other Coastal Links leaders from the West Coast.

Pedersen said that minerals worth billions of dollars have been extracted for decades, yet extreme poverty and food insecurity have continued to pervade the region.

Pedersen said there is no fair distribution of the wealth of these mineral resources — it goes into the pockets of a few and a lot of it is sent outside the country.

The report finds that mineral extraction in South Africa and other parts of the world continues to produce major social and environmental destruction. The mining of mineral sands is no exception and the report shows that continued extensification of mining on the West Coast will add to the existing social, environmental and climate crisis.

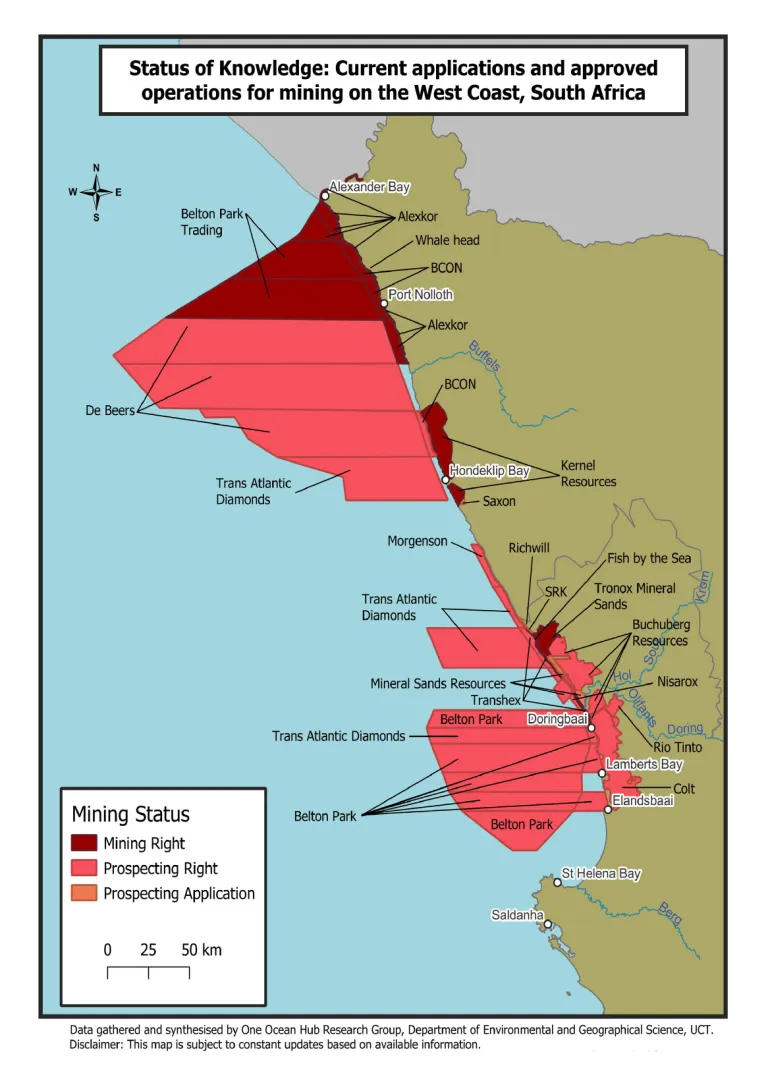

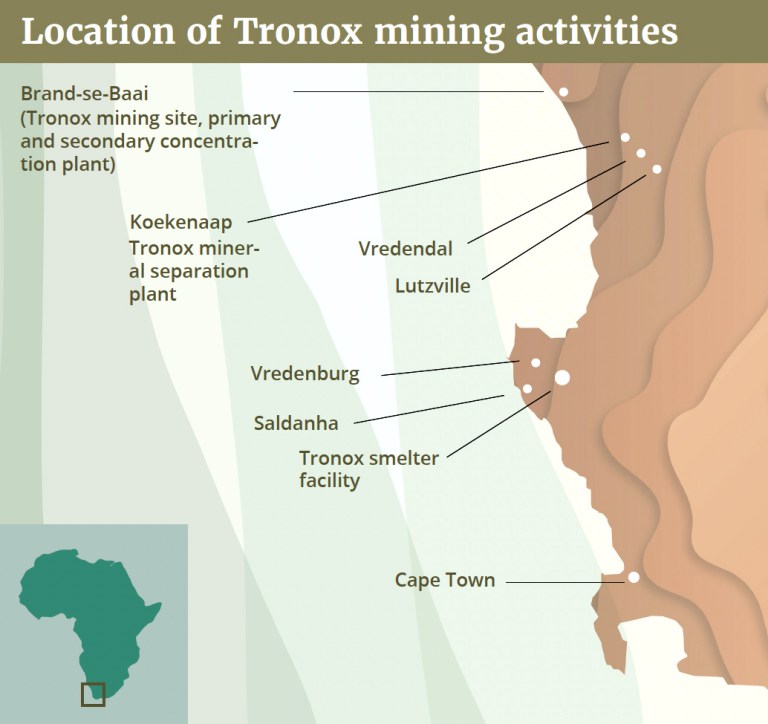

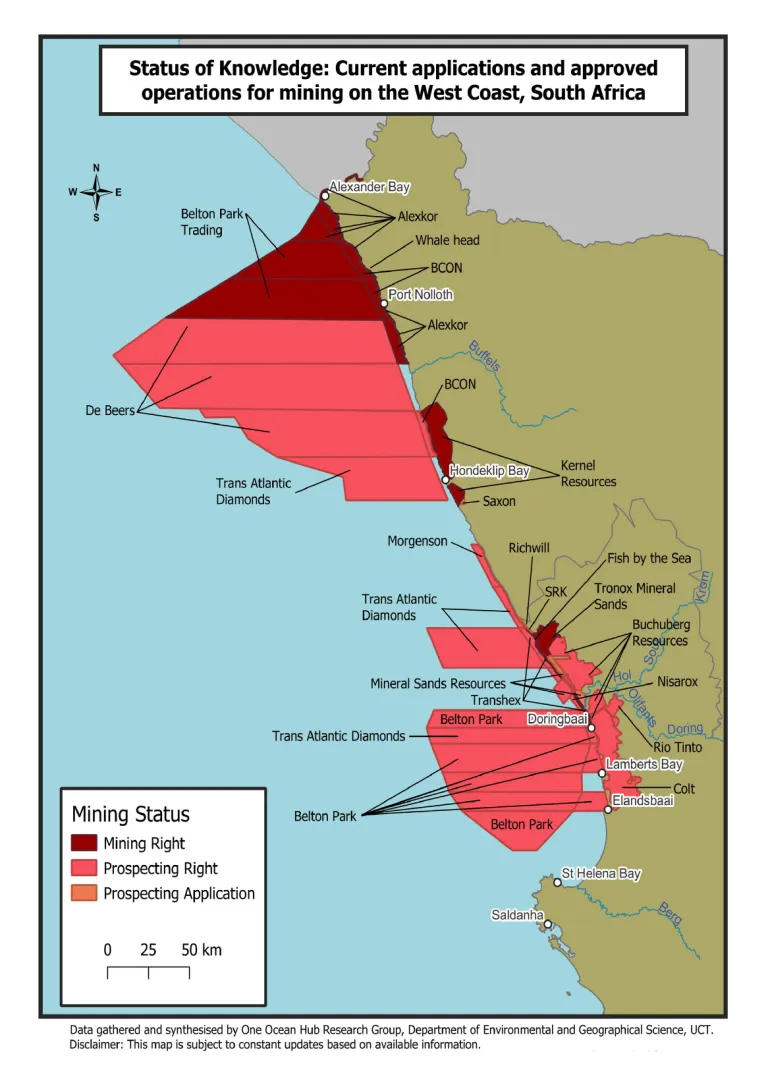

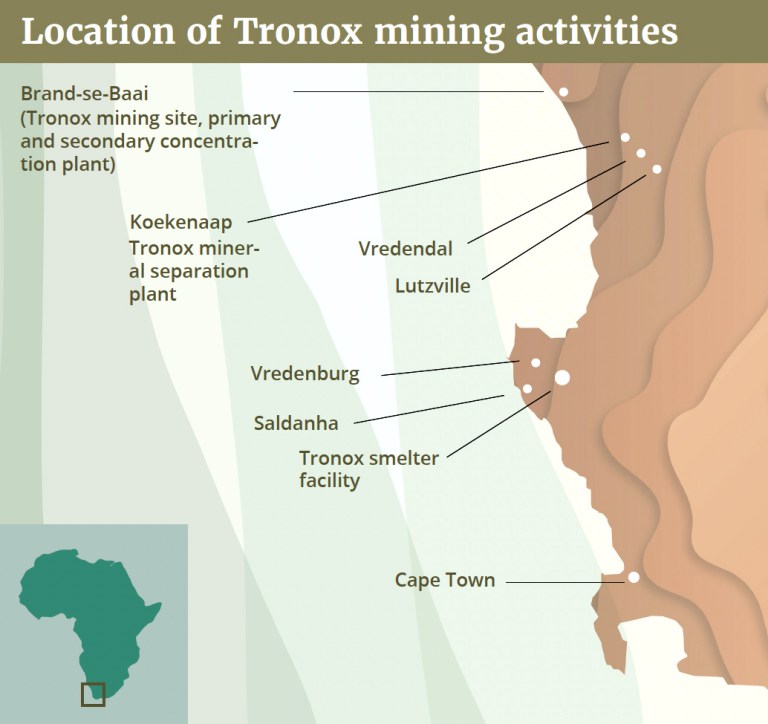

In the report, Pedersen looked at Tronox Holdings which operates Namakwa Sands (Tronox Mineral Sands) in Saldanha and Matzikama, and KwaZulu-Natal Sands in Empangeni. Pedersen noted that these operations were less visible on the radar because they did more “clean business” and good PR work, so you don’t see the same injustice. But when he looked at the scale and size of the company, Pedersen this was the one they needed to pay attention to.

(Graphic: Transnational Institute)

What are the minerals in the sands and why are they so valuable?

“Every person living on the West Coast of South Africa knows that the sands there are the source of life. People walk the sands, launch their boats from beaches, catch fish from near a seabed made of sand, harvest plants (wild and cultivated) and raise domestic animals on the sandy stretches of coastal lands, and they have done so for centuries.

“They also know the sands have been a source of profit-making for the last century and a half and that their sands are again up for grabs. But why is this sand so interesting from a capitalist point of view? What does it contain and what is it used for?” Pedersen asked in his report.

South Africa’s minister of International Relations and Cooperation, Naledi Pandor, said in the Financial Times:“ South Africa is a significant supplier of critical minerals to the US. If we lose Agoa membership, it could have negative ramifications for the US. In the global fight against climate change, demand for critical minerals has become a significant factor. In 2021, the US imported nearly 100% of its chromium from South Africa, as well as over 25% of its manganese, titanium, and platinum. We also supply of 12 of the 50 mineral products identified by the US Geological Survey as critical for US interests.”

A large amount of the minerals Pandor refers to here come from the West Coast, but what exactly are the minerals being extracted from the sands?

Pedersen said the sand on the West Coast is rich in zircon, ilmenite and rutile, the so-called heavy minerals. Rutile is the most valuable as it is a mineral containing 95% titanium, used for aircraft, architectural products, industrial processes, sporting equipment and numerous other applications.

“The US is just one of the countries that need titanium for all these different industries. The Financial Times articles state that 25% of titanium comes from South Africa for US imports. In South Africa, 60% of Tronox’s titanium comes from the West Coast and 40% comes from the East Coast. Tronox is the biggest producer of titanium in South Africa, so it is the biggest player, ” Pedersen said.

“This is why the minister was putting forward that South Africa had to maintain good trade relations — and this was only titanium, there are many more [minerals] at play.”

Pedersen explained that heavy earthmoving equipment (excavators and trucks) were used to excavate and transport the sand from the mining sites to the primary and secondary concentration plants. This concentration process takes place at or near the mining site before the concentrate is transported by truck to a mineral separation plant where it is further separated into zircon, ilmenite and rutile.

Sand mining extraction northwest of Papendorp, near the Oilifants River. (Photo: Transnational Institute)

These three minerals (zircon, ilmenite and rutile) are then further processed and transported as industrial feedstock to Saldanha before being exported to overseas markets.

Pederson said zircon, a hard mineral that comes in various colours and is found as grains in sand, is used either directly as a strong metallic element in ceramics or processed into zirconium chemicals and zirconium metal.

“South Africa’s share of world zircon production was 25% in 2020 and the vast majority (97%) of zirconium chemicals and metals produced worldwide originate in mineral sands.

“Tronox alone accounted for 60% of that production of which approximately 40% is derived from the West Coast sands and the remainder from KwaZulu-Natal and its Australian mines. Zircon is a strong and heat-resistant mineral that is applicable in a wide range of products. The majority is used in ceramics, whereas the zirconium metal and chemicals are used in the production of solar panels, TV screens, jet engines, hydrogen fuel cells, nuclear reactor cooling systems, vehicle components and more,” he said.

The Sand Worth Billions report analysis reveals that the sands are a source of minerals used to manufacture a wide range of end-products that most people all over the world depend on to meet their daily material needs, such as housing, food and transportation. The minerals feed into multi-billion dollar industries and the South African sands are too valuable for mining corporations to leave untouched.

Communities left high and dry

Pedersen continued, “Corporations will continue exploration and extraction of heavy mineral sands provided they can control the cost of production and that risks, such as political instability and rising energy costs, are considered manageable.

“This also means competition for the coastal lands and the sea, between local communities and mining companies, will continue and possibly lead to further tensions,” he said.

This report will be one ingredient for Masifundise Development Trust’s Fisher People’s Tribunal in August this year, to strengthen the voices of fisherfolk and the information will also be disseminated to affected communities.

Pedersen said, “We need to get a broader and better understanding of how the mining industry works… We have to look beyond the side of extraction because this is what most people working on mining issues look at. They are not looking at the value chain and what happens to the minerals, where they go, who profits from them, and where the profit is made. They also don’t look at who the people behind the mining companies are, the shareholders etc. These companies depend on investments and capital to expand their business and if they don’t get that capital then they won’t expand, that’s what history tells us.”

Pedersen said that sand mining was a billion-dollar industry and only a tiny proportion of the profits stayed in South Africa.

“They take the minerals, ship them offshore to some other Tronox subsidiaries that process these raw materials into other commodities like titanium powder which is then sold from other countries. This means the profit from this activity is not a profit made in South Africa,” he said.

A view of MSP Koekenaap (Tronox mine) in the Namakwa Sands of South Africa. (Photo: Transnational Institute)

Slow violence on the West Coast

A speak-out event was hosted by Masifundise in April 2024 where the report’s author Carsten Pedersen, Andre Cloete, and South African lead organiser of WoMin African Alliance Alexandria Hotz, detailed the report’s contents and “the slow violence of mining of the West Coast”.

During the discussion, Pedersen said ‘slow violence’ was not something that could be tracked over six months or one year. It represents the ongoing extraction of wealth and the simultaneous degradation of the environment that contributed to the erosion of livelihoods of people in coastal areas.

“When areas are grabbed by mining companies, these same areas and their resources are not available for the local population… for their livelihoods, food production, and the local economy.”

He said the resources along the coast should be utilised and developed in a way that benefits the people in the area.

“Once the territories are grabbed, they are no longer available and accessible for local communities. This closes down the opportunities for [local] economic development. There’s no sharing of all that wealth. In Lutzville, poverty has increased, crime rates have increased, and it’s not safe to walk in the streets. This is all part of the slow violence, and the result of the lack of sharing of wealth — which is, to a large extent, the responsibility of the mining companies and government,” Pederson said.

Hotz from WoMin added that these operations have an impact on the ecosystems, and ocean, then further impact the livelihoods of small-scale fishers already dependent on the ocean

In an interview with Daily Maverick, Hotz said there were multiple forms of this slow violence and there was a gendered experience to it. But she said the first experience was that people being separated from their land as indigenous people was a form of violence that unfortunately South Africans were all too familiar with.

“Because we have been in processes of dispossession, from colonialism, under apartheid, and now we are seeing new forms of land grabbing — which is violent, through mining applications and how the DMRP and other departments give away communities land without consultation or consent from communities.

“What that means is it creates a separation of communities from the land, from access to resources, the deepening of inequality and poverty in our communities and the reliance on grants because no work is coming to communities, the livelihoods have changed, they’re no longer able to fish or to grow food or rear cattle, etc,” she said.

Hotz said that women had a particular burden as they care for families mostly — from looking after fathers, sons and husbands who become ill working in mines, to holding households together and providing food, etc.

“There’s a whole cycle of violence. Last year in August in Concordia, a small town in the Northern Cape, women led a protest to defend communal land from being mined on and 29 community members were arrested,” she said.

There were also leaders of movements being assassinated for defending land, such as land activist and chairperson of the Amadiba Crisis Committee (ACC) Sikhosiphi “Bazooka” Rhadebe, who was murdered in 2016.

Tronox and respecting its host communities

When approached for a response to specific questions by Daily Maverick, Tronox referred to their 2022 Sustainability Report. Under the framework “Respecting Our Communities”, the report describes that Tronox works in respectful partnership with indigenous communities to protect their heritage and cultural values as they manage operations located on traditional lands in Australia and South Africa.

They also claim to seek out opportunities to contribute to the local economy by supporting indigenous-owned businesses, and to protect the native lands these communities call home.

(Graphic: Transnational Institute)

They say they engage in long-term relationships with traditional owner groups across all operations to determine the best ways to preserve and protect cultural heritage values and bring respectful economic development to their communities.

The report states, “Tronox operates alongside indigenous communities in South Africa, and is committed to the objectives set out in the National Development Plan, which aims to eliminate poverty and reduce inequality by 2030. Through our Social and Labor Plans (SLPs), we have made valuable contributions towards supporting local Black-owned businesses in these communities,

“In 2022, Tronox invested R14-million (more than $817,000) in local business beneficiaries, which included 13 black-owned businesses. Seven of these were black women-owned businesses in industries like construction that align with our goals of championing greater gender diversity in traditionally male-dominated industries.”

In addition to economic development support, the report states that Tronox supports the host communities where they operate through Local Economic Development (LED) projects that include “building schools and homes, supporting STEM programmes, improving access to water and indoor plumbing, and even bringing the first veterinary clinic to one community”.

However, members of the communities along the West Coast, such as Cloete, and organisations supporting these communities, like Masifundise and WoMin, said that the ongoing extraction of minerals by these mining companies causes long-lasting social and environmental destruction.

Cloete said this was particularly the case when it comes to jobs mining companies provide, as they often only last for a few months with no sustainable economic upliftment for the locals in the communities. DM

Sand mining in Matzikama, the northernmost part of the Western Cape. (Photo: Transnational Institute)

By Kristin Engel - 07 May 2024

Mining has existed on the West Coast for over 100 years. A new report looks at what these valuable mineral sands are and how surrounding communities still suffer extreme poverty, unemployment and food insecurity. At the heart of this narrative are the heavy minerals —- zircon, ilmenite, and rutile — concealed within the grains of sand.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Originally from Papendorp and now residing in Doringbaai, chairperson of Coastal Links Western Cape Andre Cloete has been a fisher for over 20 years. He said that mining has left destruction in his community and all along the West Coast with no rehabilitation when mining companies finish their activity. He says it’s not just the physical environment but also the community that is suffering.

“One of the main things is that they [mining companies] leave the physical environment in a state and they don’t invest in the communities. They provide jobs only for a certain time, a few months, it’s all contractual and not permanent… People don’t thrive or prosper from these jobs while they [mining companies] on the other hand reap the benefits. You can see it.

“For the past five years, if we look at snoek, you don’t get as much as you normally do because of all these explorations happening now… Even with crayfish in Elands Bay, it’s crayfish season now and there’s no lobster during the day. We have to work at night because you don’t get anything during the day… Normally you get tons of fish and lobster in Elands Bay, now it’s only during the night because there’s less disturbance during the night,” Cloete said.

Cloete said there is no medical clinic in Papendorp, with community members having to travel to either Lutzville or Dorongbaai for treatment, yet mining companies were making billions from the minerals extracted from these communities.

This is the story of one of the contributors of a report, showing the impact of the historical reaping of minerals from poverty-stricken communities on the West Coast for billions over time.

“The Sand Worth Billions: How mining companies are reshaping South Africa’s West Coast” was authored by Carsten Pedersen from the Transnational Institute. The initial research and work of the report was conducted by Masifundise Development Trust, Cloete, as well as a few other Coastal Links leaders from the West Coast.

Pedersen said that minerals worth billions of dollars have been extracted for decades, yet extreme poverty and food insecurity have continued to pervade the region.

Pedersen said there is no fair distribution of the wealth of these mineral resources — it goes into the pockets of a few and a lot of it is sent outside the country.

The report finds that mineral extraction in South Africa and other parts of the world continues to produce major social and environmental destruction. The mining of mineral sands is no exception and the report shows that continued extensification of mining on the West Coast will add to the existing social, environmental and climate crisis.

In the report, Pedersen looked at Tronox Holdings which operates Namakwa Sands (Tronox Mineral Sands) in Saldanha and Matzikama, and KwaZulu-Natal Sands in Empangeni. Pedersen noted that these operations were less visible on the radar because they did more “clean business” and good PR work, so you don’t see the same injustice. But when he looked at the scale and size of the company, Pedersen this was the one they needed to pay attention to.

(Graphic: Transnational Institute)

What are the minerals in the sands and why are they so valuable?

“Every person living on the West Coast of South Africa knows that the sands there are the source of life. People walk the sands, launch their boats from beaches, catch fish from near a seabed made of sand, harvest plants (wild and cultivated) and raise domestic animals on the sandy stretches of coastal lands, and they have done so for centuries.

“They also know the sands have been a source of profit-making for the last century and a half and that their sands are again up for grabs. But why is this sand so interesting from a capitalist point of view? What does it contain and what is it used for?” Pedersen asked in his report.

South Africa’s minister of International Relations and Cooperation, Naledi Pandor, said in the Financial Times:“ South Africa is a significant supplier of critical minerals to the US. If we lose Agoa membership, it could have negative ramifications for the US. In the global fight against climate change, demand for critical minerals has become a significant factor. In 2021, the US imported nearly 100% of its chromium from South Africa, as well as over 25% of its manganese, titanium, and platinum. We also supply of 12 of the 50 mineral products identified by the US Geological Survey as critical for US interests.”

A large amount of the minerals Pandor refers to here come from the West Coast, but what exactly are the minerals being extracted from the sands?

Pedersen said the sand on the West Coast is rich in zircon, ilmenite and rutile, the so-called heavy minerals. Rutile is the most valuable as it is a mineral containing 95% titanium, used for aircraft, architectural products, industrial processes, sporting equipment and numerous other applications.

“The US is just one of the countries that need titanium for all these different industries. The Financial Times articles state that 25% of titanium comes from South Africa for US imports. In South Africa, 60% of Tronox’s titanium comes from the West Coast and 40% comes from the East Coast. Tronox is the biggest producer of titanium in South Africa, so it is the biggest player, ” Pedersen said.

“This is why the minister was putting forward that South Africa had to maintain good trade relations — and this was only titanium, there are many more [minerals] at play.”

Pedersen explained that heavy earthmoving equipment (excavators and trucks) were used to excavate and transport the sand from the mining sites to the primary and secondary concentration plants. This concentration process takes place at or near the mining site before the concentrate is transported by truck to a mineral separation plant where it is further separated into zircon, ilmenite and rutile.

Sand mining extraction northwest of Papendorp, near the Oilifants River. (Photo: Transnational Institute)

These three minerals (zircon, ilmenite and rutile) are then further processed and transported as industrial feedstock to Saldanha before being exported to overseas markets.

Pederson said zircon, a hard mineral that comes in various colours and is found as grains in sand, is used either directly as a strong metallic element in ceramics or processed into zirconium chemicals and zirconium metal.

“South Africa’s share of world zircon production was 25% in 2020 and the vast majority (97%) of zirconium chemicals and metals produced worldwide originate in mineral sands.

“Tronox alone accounted for 60% of that production of which approximately 40% is derived from the West Coast sands and the remainder from KwaZulu-Natal and its Australian mines. Zircon is a strong and heat-resistant mineral that is applicable in a wide range of products. The majority is used in ceramics, whereas the zirconium metal and chemicals are used in the production of solar panels, TV screens, jet engines, hydrogen fuel cells, nuclear reactor cooling systems, vehicle components and more,” he said.

The Sand Worth Billions report analysis reveals that the sands are a source of minerals used to manufacture a wide range of end-products that most people all over the world depend on to meet their daily material needs, such as housing, food and transportation. The minerals feed into multi-billion dollar industries and the South African sands are too valuable for mining corporations to leave untouched.

Communities left high and dry

Pedersen continued, “Corporations will continue exploration and extraction of heavy mineral sands provided they can control the cost of production and that risks, such as political instability and rising energy costs, are considered manageable.

“This also means competition for the coastal lands and the sea, between local communities and mining companies, will continue and possibly lead to further tensions,” he said.

This report will be one ingredient for Masifundise Development Trust’s Fisher People’s Tribunal in August this year, to strengthen the voices of fisherfolk and the information will also be disseminated to affected communities.

Pedersen said, “We need to get a broader and better understanding of how the mining industry works… We have to look beyond the side of extraction because this is what most people working on mining issues look at. They are not looking at the value chain and what happens to the minerals, where they go, who profits from them, and where the profit is made. They also don’t look at who the people behind the mining companies are, the shareholders etc. These companies depend on investments and capital to expand their business and if they don’t get that capital then they won’t expand, that’s what history tells us.”

Pedersen said that sand mining was a billion-dollar industry and only a tiny proportion of the profits stayed in South Africa.

“They take the minerals, ship them offshore to some other Tronox subsidiaries that process these raw materials into other commodities like titanium powder which is then sold from other countries. This means the profit from this activity is not a profit made in South Africa,” he said.

A view of MSP Koekenaap (Tronox mine) in the Namakwa Sands of South Africa. (Photo: Transnational Institute)

Slow violence on the West Coast

A speak-out event was hosted by Masifundise in April 2024 where the report’s author Carsten Pedersen, Andre Cloete, and South African lead organiser of WoMin African Alliance Alexandria Hotz, detailed the report’s contents and “the slow violence of mining of the West Coast”.

During the discussion, Pedersen said ‘slow violence’ was not something that could be tracked over six months or one year. It represents the ongoing extraction of wealth and the simultaneous degradation of the environment that contributed to the erosion of livelihoods of people in coastal areas.

“When areas are grabbed by mining companies, these same areas and their resources are not available for the local population… for their livelihoods, food production, and the local economy.”

He said the resources along the coast should be utilised and developed in a way that benefits the people in the area.

“Once the territories are grabbed, they are no longer available and accessible for local communities. This closes down the opportunities for [local] economic development. There’s no sharing of all that wealth. In Lutzville, poverty has increased, crime rates have increased, and it’s not safe to walk in the streets. This is all part of the slow violence, and the result of the lack of sharing of wealth — which is, to a large extent, the responsibility of the mining companies and government,” Pederson said.

Hotz from WoMin added that these operations have an impact on the ecosystems, and ocean, then further impact the livelihoods of small-scale fishers already dependent on the ocean

In an interview with Daily Maverick, Hotz said there were multiple forms of this slow violence and there was a gendered experience to it. But she said the first experience was that people being separated from their land as indigenous people was a form of violence that unfortunately South Africans were all too familiar with.

“Because we have been in processes of dispossession, from colonialism, under apartheid, and now we are seeing new forms of land grabbing — which is violent, through mining applications and how the DMRP and other departments give away communities land without consultation or consent from communities.

“What that means is it creates a separation of communities from the land, from access to resources, the deepening of inequality and poverty in our communities and the reliance on grants because no work is coming to communities, the livelihoods have changed, they’re no longer able to fish or to grow food or rear cattle, etc,” she said.

Hotz said that women had a particular burden as they care for families mostly — from looking after fathers, sons and husbands who become ill working in mines, to holding households together and providing food, etc.

“There’s a whole cycle of violence. Last year in August in Concordia, a small town in the Northern Cape, women led a protest to defend communal land from being mined on and 29 community members were arrested,” she said.

There were also leaders of movements being assassinated for defending land, such as land activist and chairperson of the Amadiba Crisis Committee (ACC) Sikhosiphi “Bazooka” Rhadebe, who was murdered in 2016.

Tronox and respecting its host communities

When approached for a response to specific questions by Daily Maverick, Tronox referred to their 2022 Sustainability Report. Under the framework “Respecting Our Communities”, the report describes that Tronox works in respectful partnership with indigenous communities to protect their heritage and cultural values as they manage operations located on traditional lands in Australia and South Africa.

They also claim to seek out opportunities to contribute to the local economy by supporting indigenous-owned businesses, and to protect the native lands these communities call home.

(Graphic: Transnational Institute)

They say they engage in long-term relationships with traditional owner groups across all operations to determine the best ways to preserve and protect cultural heritage values and bring respectful economic development to their communities.

The report states, “Tronox operates alongside indigenous communities in South Africa, and is committed to the objectives set out in the National Development Plan, which aims to eliminate poverty and reduce inequality by 2030. Through our Social and Labor Plans (SLPs), we have made valuable contributions towards supporting local Black-owned businesses in these communities,

“In 2022, Tronox invested R14-million (more than $817,000) in local business beneficiaries, which included 13 black-owned businesses. Seven of these were black women-owned businesses in industries like construction that align with our goals of championing greater gender diversity in traditionally male-dominated industries.”

In addition to economic development support, the report states that Tronox supports the host communities where they operate through Local Economic Development (LED) projects that include “building schools and homes, supporting STEM programmes, improving access to water and indoor plumbing, and even bringing the first veterinary clinic to one community”.

However, members of the communities along the West Coast, such as Cloete, and organisations supporting these communities, like Masifundise and WoMin, said that the ongoing extraction of minerals by these mining companies causes long-lasting social and environmental destruction.

Cloete said this was particularly the case when it comes to jobs mining companies provide, as they often only last for a few months with no sustainable economic upliftment for the locals in the communities. DM

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge