WILDLIFE CRIME/TRADE/BREEDING

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75641

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: WILDLIFE CRIME/TRADE/BREEDING

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 66797

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: WILDLIFE CRIME/TRADE/BREEDING

WILDLIFE SCANDAL

Claims of animal abuse swirl around long, murky probe into death of South African giraffes in Brazil

(Photo: Harshil Gudka-Unsplash)

By Caryn Dolley | 11 Sep 2023

The unusual cargo of 18 giraffes that landed in Brazil in 2021 has resulted in a years-long scandal, shrouded in police investigations and allegations of animal mistreatment after four of them died.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

On 11 November 2021, extraordinary “cargo” landed in Brazil. Eighteen giraffes arrived at an airport there – they had been exported from South Africa and some were meant to head to BioParque do Rio, a private zoo in Rio de Janeiro.

But the animals have become the centre of a years-long scandal involving a police investigation in Brazil and allegations of animal mistreatment.

After their arrival in Brazil in 2021, three of the giraffes died following their escape from a holding area they were being kept in while adapting to their new surroundings.

On 8 July 2023, a fourth giraffe died, putting the matter back into focus.

Daily Maverick has established that the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment is aware of what happened in Brazil but has not been informed of the findings of investigations carried out there.

It is understood that the surviving 14 giraffes are being kept at the Portobello Resort and Safari in Mangaratiba, along Rio de Janeiro’s south coast.

Daily Maverick sent questions to a representative of a company in Johannesburg that, according to its website, has its own farms and specialises in giraffe exports, to check if it was linked to the animals that ended up in Brazil, but did not receive any response to emails or a text message.

The 18 giraffes were exported to Brazil in November 2021 via a chartered flight from OR Tambo International Airport. This, based on one Brazilian government report, cost more than a million (presumably US) dollars.

Crates and cranes

According to the online magazine International Transport Journal: “Intradco Global and Chapman Freeborn ensured the giraffes’ speedy loading to reduce the time spent on the ground at the airport. After arriving in Rio de Janeiro, cranes were used to efficiently offload the six crates…”

Daily Maverick twice emailed questions about the giraffes to Intradco Global and Chapman Freeborn, but no response had been received by the time of publication.

Deaths after escape

In a statement in January 2022, BioParque do Rio said the 18 giraffes came from “an authorised site for sustainable management and community development with these species in South Africa”.

“All logistics were monitored by a… team specialised in handling to ensure the safety and well-being of the animals,” it said.

Some of the giraffes exported from South Africa to Brazil in 2021 that sparked a police investigation in that country, resulting in arrests. (Photo: Brazil’s Federal Police)

The zoo confirmed the deaths of the three giraffes. “During management operations, a group of giraffes escaped from a management area, where their adaptation takes place and, after containment and return to the pens, three… died,” it said.

After the first three giraffes died in December 2021, investigations were launched.

At the end of 2021 Brazil’s Federal Police said that two men were arrested for mistreating the (at that stage) 15 animals. It was not clear what happened to them.

In 2022 the Federal Police issued another statement saying it had presented its findings about its investigation. “During the investigation, it remained clear that there were deliberate failures by public servants in the process that authorised the importation of animals to Brazil,” it said.

‘Routine of mistreatment’

The investigation found that focus was placed on reducing costs, which was detrimental to the animals.

“All 18… specimens were subjected to a routine of mistreatment, resulting in the death of three… of the giraffes,” the Federal Police’s statement said.

“…[It] should be noted that the purpose of the police inquiry is to investigate any criminal conduct committed during the import process and in the maintenance of animals… [N]othing prevents other individuals or legal entities from being held responsible… in the civil and/or administrative sphere.”

|Some findings stated that the ‘lack of… adequate enclosures resulted in the animals being kept in a situation of abuse’.

A March 2022 report, under a Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama) letterhead, and also Brazil’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change, detailed other issues surrounding the giraffes.

It said that after the deaths of the three giraffes at the end of 2021 a threefold investigation was launched into the importation process, circumstances around the dead animals and the conditions under which the 15 surviving animals were being kept.

Some findings stated that the “lack of… adequate enclosures resulted in the animals being kept in a situation of abuse”.

The report said that in February 2022 police officers had exhumed the bodies of the three dead giraffes as part of their investigations. It also suggested the surviving animals should be repatriated and, until then, kept at the Portobello safari resort.

Parasite discovered

In response to the fourth giraffe’s death in July, Ibama said that the Haemonchus parasite had been detected in the animal, which had been undergoing treatment for this.

Meanwhile, on 8 July, the day the fourth giraffe died, BioParque do Rio said that, during routine procedures, the Haemonchus parasite was discovered in six giraffes.

“The technical committee, made up of six veterinarians, immediately started a medication protocol, placing the animals in an isolated enclosure and under intensive observation,” Ibama said.

“Five animals responded quickly to treatment. However, one of them showed resistance to the drug. During the last week, the technical team started other treatment protocols.”

The giraffe that had not responded well to the treatment had suddenly deteriorated and died.

Bioparque do Rio was involved in the import of 18 giraffes from South Africa in 2021. Four have since died. (Photo: Bioparque do Rio copy)

Permit issued

South Africa’s Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment told Daily Maverick last week that it was aware of some of what had transpired in Brazil.

Spokesperson Peter Mbelengwa said that on 25 March 2022 it had received a query from the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (Cites) management authority of Brazil about the three giraffes that had died.

He said that a Cites permit, which stated the holder of it should contact an authorised environmental management inspector 48 hours before import or export to arrange an inspection, had been issued.

Mbelengwa said the relevant freight agent “booked for an inspection of the consignment of 18 giraffes destined for Brazil on a charter flight and the inspection appointment was… confirmed by [the department].”

An environment management inspector conducted an inspection on 11 November 2021 and endorsed the Cites permit at a warehouse at OR Tambo International Airport.

“At the time of the inspection, all 18 giraffes appeared to be in good health,” Mbelengwa said.

“The Brazilian authorities did not share the outcomes of their investigation other than to say that they were concerned about the welfare of the animals at the zoo where they were kept and that they would remove them from that zoo.”

Tall order

A quick online search shows that giraffes can sell from about R14,500 for a young animal to about R25,000 for an adult bull in South Africa. In terms of exporting, the government says that “to export animals or genetic material such as embryos, ova or semen from [SA], you must apply for an export permit from the Registrar of Animal Improvement”. A relevant breeders’ society or registering authority also has to recommend an application to export. According to another South African government website, this country is a founding member of Cites, which “aims to ensure that international trade in listed species of wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival in the wild”. Giraffes are on the Cites Appendix II list, meaning the animals “are not necessarily now threatened with extinction but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled”. DM

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R29.

Claims of animal abuse swirl around long, murky probe into death of South African giraffes in Brazil

(Photo: Harshil Gudka-Unsplash)

By Caryn Dolley | 11 Sep 2023

The unusual cargo of 18 giraffes that landed in Brazil in 2021 has resulted in a years-long scandal, shrouded in police investigations and allegations of animal mistreatment after four of them died.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

On 11 November 2021, extraordinary “cargo” landed in Brazil. Eighteen giraffes arrived at an airport there – they had been exported from South Africa and some were meant to head to BioParque do Rio, a private zoo in Rio de Janeiro.

But the animals have become the centre of a years-long scandal involving a police investigation in Brazil and allegations of animal mistreatment.

After their arrival in Brazil in 2021, three of the giraffes died following their escape from a holding area they were being kept in while adapting to their new surroundings.

On 8 July 2023, a fourth giraffe died, putting the matter back into focus.

Daily Maverick has established that the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment is aware of what happened in Brazil but has not been informed of the findings of investigations carried out there.

It is understood that the surviving 14 giraffes are being kept at the Portobello Resort and Safari in Mangaratiba, along Rio de Janeiro’s south coast.

Daily Maverick sent questions to a representative of a company in Johannesburg that, according to its website, has its own farms and specialises in giraffe exports, to check if it was linked to the animals that ended up in Brazil, but did not receive any response to emails or a text message.

The 18 giraffes were exported to Brazil in November 2021 via a chartered flight from OR Tambo International Airport. This, based on one Brazilian government report, cost more than a million (presumably US) dollars.

Crates and cranes

According to the online magazine International Transport Journal: “Intradco Global and Chapman Freeborn ensured the giraffes’ speedy loading to reduce the time spent on the ground at the airport. After arriving in Rio de Janeiro, cranes were used to efficiently offload the six crates…”

Daily Maverick twice emailed questions about the giraffes to Intradco Global and Chapman Freeborn, but no response had been received by the time of publication.

Deaths after escape

In a statement in January 2022, BioParque do Rio said the 18 giraffes came from “an authorised site for sustainable management and community development with these species in South Africa”.

“All logistics were monitored by a… team specialised in handling to ensure the safety and well-being of the animals,” it said.

Some of the giraffes exported from South Africa to Brazil in 2021 that sparked a police investigation in that country, resulting in arrests. (Photo: Brazil’s Federal Police)

The zoo confirmed the deaths of the three giraffes. “During management operations, a group of giraffes escaped from a management area, where their adaptation takes place and, after containment and return to the pens, three… died,” it said.

After the first three giraffes died in December 2021, investigations were launched.

At the end of 2021 Brazil’s Federal Police said that two men were arrested for mistreating the (at that stage) 15 animals. It was not clear what happened to them.

In 2022 the Federal Police issued another statement saying it had presented its findings about its investigation. “During the investigation, it remained clear that there were deliberate failures by public servants in the process that authorised the importation of animals to Brazil,” it said.

‘Routine of mistreatment’

The investigation found that focus was placed on reducing costs, which was detrimental to the animals.

“All 18… specimens were subjected to a routine of mistreatment, resulting in the death of three… of the giraffes,” the Federal Police’s statement said.

“…[It] should be noted that the purpose of the police inquiry is to investigate any criminal conduct committed during the import process and in the maintenance of animals… [N]othing prevents other individuals or legal entities from being held responsible… in the civil and/or administrative sphere.”

|Some findings stated that the ‘lack of… adequate enclosures resulted in the animals being kept in a situation of abuse’.

A March 2022 report, under a Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama) letterhead, and also Brazil’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change, detailed other issues surrounding the giraffes.

It said that after the deaths of the three giraffes at the end of 2021 a threefold investigation was launched into the importation process, circumstances around the dead animals and the conditions under which the 15 surviving animals were being kept.

Some findings stated that the “lack of… adequate enclosures resulted in the animals being kept in a situation of abuse”.

The report said that in February 2022 police officers had exhumed the bodies of the three dead giraffes as part of their investigations. It also suggested the surviving animals should be repatriated and, until then, kept at the Portobello safari resort.

Parasite discovered

In response to the fourth giraffe’s death in July, Ibama said that the Haemonchus parasite had been detected in the animal, which had been undergoing treatment for this.

Meanwhile, on 8 July, the day the fourth giraffe died, BioParque do Rio said that, during routine procedures, the Haemonchus parasite was discovered in six giraffes.

“The technical committee, made up of six veterinarians, immediately started a medication protocol, placing the animals in an isolated enclosure and under intensive observation,” Ibama said.

“Five animals responded quickly to treatment. However, one of them showed resistance to the drug. During the last week, the technical team started other treatment protocols.”

The giraffe that had not responded well to the treatment had suddenly deteriorated and died.

Bioparque do Rio was involved in the import of 18 giraffes from South Africa in 2021. Four have since died. (Photo: Bioparque do Rio copy)

Permit issued

South Africa’s Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment told Daily Maverick last week that it was aware of some of what had transpired in Brazil.

Spokesperson Peter Mbelengwa said that on 25 March 2022 it had received a query from the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (Cites) management authority of Brazil about the three giraffes that had died.

He said that a Cites permit, which stated the holder of it should contact an authorised environmental management inspector 48 hours before import or export to arrange an inspection, had been issued.

Mbelengwa said the relevant freight agent “booked for an inspection of the consignment of 18 giraffes destined for Brazil on a charter flight and the inspection appointment was… confirmed by [the department].”

An environment management inspector conducted an inspection on 11 November 2021 and endorsed the Cites permit at a warehouse at OR Tambo International Airport.

“At the time of the inspection, all 18 giraffes appeared to be in good health,” Mbelengwa said.

“The Brazilian authorities did not share the outcomes of their investigation other than to say that they were concerned about the welfare of the animals at the zoo where they were kept and that they would remove them from that zoo.”

Tall order

A quick online search shows that giraffes can sell from about R14,500 for a young animal to about R25,000 for an adult bull in South Africa. In terms of exporting, the government says that “to export animals or genetic material such as embryos, ova or semen from [SA], you must apply for an export permit from the Registrar of Animal Improvement”. A relevant breeders’ society or registering authority also has to recommend an application to export. According to another South African government website, this country is a founding member of Cites, which “aims to ensure that international trade in listed species of wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival in the wild”. Giraffes are on the Cites Appendix II list, meaning the animals “are not necessarily now threatened with extinction but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled”. DM

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R29.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 66797

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: WILDLIFE CRIME/TRADE/BREEDING

A novel approach to make criminal justice more inclusive and responsive

27 October 2023

Today, the implementation phase of a novel project to test the use of restorative approaches to wildlife crimes will commence. The Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT), working with the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF)South Africa Khetha Programme, supported by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), National Institute for Crime Prevention and Reintegration of Offender (NICRO)and the Restorative Justice Centre, is leading this project to apply restorative justice approaches to wildlife crimes in recognition that criminal behaviour not only violates the law, but also create harms on multiple levels, including to the environment. Criminal justice systems have increasingly been called on to focus more directly on the needs and interests of victims.

The United Nations defines restorative justice as a flexible, participatory and problem-solving response to criminal behaviour, which can provide a complementary or an alternative path to justice. It can improve access to justice, particularly for victims of crime and vulnerable and marginalised populations. Restorative justice processes are uniquely suited to address some of the victims’ most important needs while achieving justice for wildlife crimes at the same time. By participating in the process, victims – which could be a landowner or ranger; or a group of people, the community, an organisation, or even a reserve - have a say in determining what would be an acceptable outcome for the process and take steps toward closure.

The project will test restorative justice approaches across a wide range of wildlife crimes, including both syndicated and non-syndicated wildlife and related offences within the criminal justice system.

This project takes place in two phases: foundational and implementation. The foundational phase, which commenced in August 2019, has resulted in the development of a new training course in South Africa as well as six trained facilitators; a series of resources detailing the applicability of wildlife crimes and provided awareness raising to over one hundred people; one comprehensive guideline and two publications. This phase is intended to develop a solid foundation for the application of restorative justice approaches to wildlife crimes.

This project is focused in the Ehlanzeni Municipal District, working closely with key stakeholders from the Kruger National Park, Mpumalanga Tourism and Parks Agency, Sabi Sand Nature Reserve, Traditional and Community Leaders, the South African Police Service and the National Prosecuting Authority.

Restorative justice is a well-established approach to justice that can have meaningful impacts on combatting wildlife offences in South Africa. For more information on the project please get in touch with Ashleigh Dore at ashleighd@ewt.org.za. and if you have a case you believe would make a suitable test case, please kindly email details to RJ@ewt.org.za (the official referral email for the project).

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 66797

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: WILDLIFE CRIME/TRADE/BREEDING

Shades of grey — why wildlife crime is proving complicated and hard to beat

In Acornhoek, near the Kruger National Park, poachers openly sell bushmeat with half a warthog fetching R900. (Photo: Vusi Tshabalala)

By Maxcine Kater | 06 Dec 2023

Wildlife crime has many threads. It’s entangled in the very fabric of our society and we must get to grips with its subtleties if we hope to unpick it. Maxcine Kater reports.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Remember lockdown when you couldn’t get alcohol and cigarettes; when you felt trapped in your home? Perhaps it didn’t leave you with a high regard for the law or our lawmakers. Perhaps you felt few qualms getting your hands on booze and baccy any way you could, or breaking curfew when the opportunity arose.

When laws are seen to lack legitimacy, they are widely flouted. It’s a lesson we would do well to remember if we are to give our endangered wildlife a better shot at survival, reckons Lara Rall, Deputy Programme Manager with the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) South Africa.

Rall states that South Africa has no shortage of laws to protect wildlife.

“But behaviour that was deemed illegal was not always viewed as wrong or bad by all people in society,” says Rall, referring to various Covid rules and regulations that many did not agree with. In the same way, she said, “hunting inside a protected area, which is illegal to do without the necessary permits, was not always seen as wrong or bad, no matter what the law says.”

“Our legislation,” she added, was “only as good as the paper it’s written on, unless it’s legitimate in the eyes of the people it’s supposed to govern” and provided “enforcement is swift, fair and certain”.

Rall, who was among the panellists at the latest Tipping Points webinar hosted by Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation (OGRC) on November 30, made the point that South Africa has no shortage of laws to protect wildlife.

“But our legislation is only as good as the paper it’s written on unless it’s legitimate in the eyes of the people it’s supposed to govern” and provided “enforcement is swift, fair and certain”, said Rall.

Grappling with the topic, “A Thin Green Line: Balancing Customary and Traditional Law in Wildlife Trade”, the panellists agreed that on the metrics above, South Africa does not score well. Quite how this came to pass and what should be done to make things better was, however, where perspectives diverged.

Challenges

Organised and wildlife crime expert Julian Rademeyer and conservationist and community relations fundi Vusi Tshabalala stressed, respectively, the breakdown of high-level governance, and a failure to engage properly with people on the ground.

The webinar, the 18th in the Tipping Points series, also served to publicise the recently launched Khetha 2024 Story Project. Supported by USaid and WWF, the initiative seeks to deepen media coverage of the illegal wildlife trade, with a particular focus on the Greater Kruger Park area, through story grants, mentorship and webinars.

At the launch of the recent Khetha 2024 Story Project, Rob Inglis, director of Jive Media Africa, recorded key responses to questions about how the media could do a better job reporting on wildlife crime and conservation challenges in the Greater Kruger area. (Photo: © WWF | Jonathan Inglis)

Rall said that while good laws and enforcement were necessary for a functioning society, these alone would not stop wildlife crime. For this, we needed to design responses that were in touch with people’s realities. This meant including more people who lived near parks and protected areas — those most affected by poaching — in conversations about conservation.

What leads people to poach or trade illegally in wild animals and plants?

Rall doubted economic deprivation provided an adequate explanation.

“Poverty alone does not drive crime. Countries where you have high overall levels of poverty do not necessarily have higher levels of crime. It’s places that have high levels of income inequality that typically have the highest levels of crime.”

She believed a breakdown of social norms, a lack of jobs and economic opportunities, especially for the young, as well as corruption, all played a major role.

WWF SA Deputy Programme Manager Lara Rall says there is an urgent need for more inclusive discussions on wildlife crime and stories in the media that are in touch with people’s realities. (Photo: WWF | Karabo Magakane | Wild Shots Outreach)

Rob Inglis, of Jive Media, who facilitated the webinar, felt this was a complex subject that went well beyond policing and said there was a need for conversations to find solutions.

Rademeyer, who is the director of the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime’s East and Southern Africa’s research observatory, agreed.

“This is something that touches on almost every aspect of society. It’s about land ownership, poverty and inequality — deep-seated inequality, in one of the most unequal societies. It’s about crime and corruption, social development and history,” said Rademeyer.

He spoke about research work by his organisation in the Greater Kruger area and Mpumalanga which studied illicit economies and documented the convergence of different forms of organised crime, including illegal mining, cash-in-transit heists and poaching.

Linkages

The linkages were “becoming closer and closer”. Yet, so much of the focus on illegal wildlife trade was on the foot soldiers, the people at the bottom — poachers in the parks, who were expendable to the crime networks and syndicates who employed them. Similarly, arrests of thousands of individual illegal miners clogged the courts but little in the way of targeted investigations at the highest level.

“There is no clear strategy at a leadership level on how to deal with organised crime. Across South Africa, most responses seem to be knee-jerk.”

He said a void in governance and law enforcement had allowed organised crime to take root in many of our provinces. It was now reaching “frightening levels” to the extent it posed a “very real and existential threat to South Africa”.

Kruger, he said, was seen by many as a paradise and an insulated wildlife idyll, but the national park cannot be seen outside the broader society.

Exclusion

He agreed with Rall’s comments about the perceived legitimacy of the law, noting that parks had been a source of prestige for the apartheid state and to this day “many black South Africans feel excluded”.

Rademeyer traced the country’s hunting laws to the early years soon after the arrival of the Dutch in the Cape. Over time these laws, along with a stripping of black Africans of the right to hunt and own land, “deepened deprivation of rural communities”. The Game Theft Act of 1991 entrenched game ownership in the hands of few, predominantly private landowners, while hunting for the pot by African communities was criminalised.

Inequalities also persisted in the parks in the way some staff were treated. At the same time, millions of rands were being poured into the “war on poaching”, but with little going to “those on the ground whose job it is to curb poaching”.

Tshabalala, an education for sustainable development project manager with the Kruger 2 Canyons Biosphere Region, spoke about the “fence factor” — how South Africa was one of the few countries on the continent where reserves were fully fenced.

He said in countries such as Botswana, Namibia, Tanzania and Zimbabwe, wild areas were partially fenced or not fenced at all. Animals were free to roam in conservancies, owned by communities who benefited directly from hunting quotas.

‘Not my problem’

“Human-wildlife conflict is huge, but tolerance is higher because they see the benefits. In South Africa, because of the fences, tolerance is very low when (damage-causing) animals come out.” People often felt a sense of exclusion from park — and so whatever happened in a park was “really not my problem; it does not really affect me”, said Tshabalala.

Vusi Tshabalala, an avid conservation champion, reckons that young people who live on the fringes of the Kruger National Park should be benefitting more from protecting wildlife, but sadly, many have turned to poaching for a wide mix of reasons, including the simple need for bushmeat which, he says, should be become more readily available through legal channels. (Photo: © WWF | Warren Ngobeni | Wild Shots Outreach)

Drawing on his work with 86 communities and 42 different conservation projects in the Greater Kruger area, he spoke about how many people enjoyed no direct benefits from the park and consequently seldom reported family or neighbours who snared or hunted game.

Red tape, said Tshabalala, also made it onerous for locals to legally hunt for the pot, so instead of sustainable harvesting of wildlife which drew on indigenous knowledge and customs which contributed to conservation, we were seeing an increase in poaching and the illegal wildlife trade, he said.

Responding to a question from the floor, Inglis put it to the panel that the existing legal framework and government policy on wildlife ownership was perhaps biased in favour of private interests.

He spoke of a “massive uptick in snaring and poaching around national parks” as the economy slumped in the wake of Covid, “with people simply trying to survive, to eke out a living”.

In the face of rising unemployment, Rademeyer called for the creation of a wildlife economy that would allow more people to benefit. “Conservation and wild spaces are increasingly under pressure and they don’t exist without people.”

Building relationships

Tshabalala stressed that along with addressing issues of ownership of wildlife we needed to build a sense of responsibility. And he wanted to see more effort and more investment into building relationships — something that would not be achieved with laws.

Rall felt we should look beyond laws and treaties and instead seek environmental justice. This included balancing the law with the needs of the people who live with the consequences of laws, while at the same time being more respectful of indigenous knowledge systems and cultural differences.

She also felt that much media reporting on wildlife crime added to the problem. It tended to focus narrowly on poachers, criminalised communities living on the boundaries of parks while ignoring the many complexities at play. This was counterproductive to the efforts of community conservation initiatives by South African National Parks and others, she said.

In this regard, Rall and Inglis shared a few details about the Khetha 2024 Story Project.

Emerging writer Buntu Duku of Kruger2Canyon News (left) and Harriet Nimo of Wild Shots Outreach had engaging discussions at the recent launch of the Khetha 2024 Journalism Project in Hoedspruit. (Photo: © WWF | Karabo Magakane)

It involves investing in seasoned and up-and-coming journalists to encourage storytelling and making space for diverse perspectives, especially the voices of people directly affected by wildlife crime.

The thinking is that by changing perceptions and creating a deeper understanding of the complexities of wildlife crime, we could better inform approaches to address it, said Rall.

The project, designed by Roving Reporters and Jive Media Africa, includes a series of webinars which shall provide opportunities for seasoned journalists to apply for Khetha story grants. The story grants aim to assist South African and international journalists in reporting on wildlife crimes and conservation challenges in the Greater Kruger area through access to local, on-the-ground knowledge.

Rookie reporters, early career scientists and conservation enthusiasts worldwide are also invited to take part in the Khetha 2024 Story Project by joining Roving Reporters’ New Narratives ’24 team.

For further information contact esther@jivemedia.co.za. DM

Additional reporting by Matthew Hattingh.

Maxcine Kater is an environmental officer at the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment and a representative of Roving Reporters New Narratives ’24 team.

This story was produced with the support of Jive Media Africa, science communication partner to Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation.

In Acornhoek, near the Kruger National Park, poachers openly sell bushmeat with half a warthog fetching R900. (Photo: Vusi Tshabalala)

By Maxcine Kater | 06 Dec 2023

Wildlife crime has many threads. It’s entangled in the very fabric of our society and we must get to grips with its subtleties if we hope to unpick it. Maxcine Kater reports.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Remember lockdown when you couldn’t get alcohol and cigarettes; when you felt trapped in your home? Perhaps it didn’t leave you with a high regard for the law or our lawmakers. Perhaps you felt few qualms getting your hands on booze and baccy any way you could, or breaking curfew when the opportunity arose.

When laws are seen to lack legitimacy, they are widely flouted. It’s a lesson we would do well to remember if we are to give our endangered wildlife a better shot at survival, reckons Lara Rall, Deputy Programme Manager with the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) South Africa.

Rall states that South Africa has no shortage of laws to protect wildlife.

“But behaviour that was deemed illegal was not always viewed as wrong or bad by all people in society,” says Rall, referring to various Covid rules and regulations that many did not agree with. In the same way, she said, “hunting inside a protected area, which is illegal to do without the necessary permits, was not always seen as wrong or bad, no matter what the law says.”

“Our legislation,” she added, was “only as good as the paper it’s written on, unless it’s legitimate in the eyes of the people it’s supposed to govern” and provided “enforcement is swift, fair and certain”.

Rall, who was among the panellists at the latest Tipping Points webinar hosted by Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation (OGRC) on November 30, made the point that South Africa has no shortage of laws to protect wildlife.

“But our legislation is only as good as the paper it’s written on unless it’s legitimate in the eyes of the people it’s supposed to govern” and provided “enforcement is swift, fair and certain”, said Rall.

Grappling with the topic, “A Thin Green Line: Balancing Customary and Traditional Law in Wildlife Trade”, the panellists agreed that on the metrics above, South Africa does not score well. Quite how this came to pass and what should be done to make things better was, however, where perspectives diverged.

Challenges

Organised and wildlife crime expert Julian Rademeyer and conservationist and community relations fundi Vusi Tshabalala stressed, respectively, the breakdown of high-level governance, and a failure to engage properly with people on the ground.

The webinar, the 18th in the Tipping Points series, also served to publicise the recently launched Khetha 2024 Story Project. Supported by USaid and WWF, the initiative seeks to deepen media coverage of the illegal wildlife trade, with a particular focus on the Greater Kruger Park area, through story grants, mentorship and webinars.

At the launch of the recent Khetha 2024 Story Project, Rob Inglis, director of Jive Media Africa, recorded key responses to questions about how the media could do a better job reporting on wildlife crime and conservation challenges in the Greater Kruger area. (Photo: © WWF | Jonathan Inglis)

Rall said that while good laws and enforcement were necessary for a functioning society, these alone would not stop wildlife crime. For this, we needed to design responses that were in touch with people’s realities. This meant including more people who lived near parks and protected areas — those most affected by poaching — in conversations about conservation.

What leads people to poach or trade illegally in wild animals and plants?

Rall doubted economic deprivation provided an adequate explanation.

“Poverty alone does not drive crime. Countries where you have high overall levels of poverty do not necessarily have higher levels of crime. It’s places that have high levels of income inequality that typically have the highest levels of crime.”

She believed a breakdown of social norms, a lack of jobs and economic opportunities, especially for the young, as well as corruption, all played a major role.

WWF SA Deputy Programme Manager Lara Rall says there is an urgent need for more inclusive discussions on wildlife crime and stories in the media that are in touch with people’s realities. (Photo: WWF | Karabo Magakane | Wild Shots Outreach)

Rob Inglis, of Jive Media, who facilitated the webinar, felt this was a complex subject that went well beyond policing and said there was a need for conversations to find solutions.

Rademeyer, who is the director of the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime’s East and Southern Africa’s research observatory, agreed.

- A respected journalist and author of the definitive book on rhino poaching, Killing for Profit, Rademeyer said there were few areas that were black and white. “We are dealing with shades of grey”, and this was often missed in day-to-day media reporting on poaching.

“This is something that touches on almost every aspect of society. It’s about land ownership, poverty and inequality — deep-seated inequality, in one of the most unequal societies. It’s about crime and corruption, social development and history,” said Rademeyer.

He spoke about research work by his organisation in the Greater Kruger area and Mpumalanga which studied illicit economies and documented the convergence of different forms of organised crime, including illegal mining, cash-in-transit heists and poaching.

Linkages

The linkages were “becoming closer and closer”. Yet, so much of the focus on illegal wildlife trade was on the foot soldiers, the people at the bottom — poachers in the parks, who were expendable to the crime networks and syndicates who employed them. Similarly, arrests of thousands of individual illegal miners clogged the courts but little in the way of targeted investigations at the highest level.

“There is no clear strategy at a leadership level on how to deal with organised crime. Across South Africa, most responses seem to be knee-jerk.”

He said a void in governance and law enforcement had allowed organised crime to take root in many of our provinces. It was now reaching “frightening levels” to the extent it posed a “very real and existential threat to South Africa”.

Kruger, he said, was seen by many as a paradise and an insulated wildlife idyll, but the national park cannot be seen outside the broader society.

Exclusion

He agreed with Rall’s comments about the perceived legitimacy of the law, noting that parks had been a source of prestige for the apartheid state and to this day “many black South Africans feel excluded”.

Rademeyer traced the country’s hunting laws to the early years soon after the arrival of the Dutch in the Cape. Over time these laws, along with a stripping of black Africans of the right to hunt and own land, “deepened deprivation of rural communities”. The Game Theft Act of 1991 entrenched game ownership in the hands of few, predominantly private landowners, while hunting for the pot by African communities was criminalised.

Inequalities also persisted in the parks in the way some staff were treated. At the same time, millions of rands were being poured into the “war on poaching”, but with little going to “those on the ground whose job it is to curb poaching”.

Tshabalala, an education for sustainable development project manager with the Kruger 2 Canyons Biosphere Region, spoke about the “fence factor” — how South Africa was one of the few countries on the continent where reserves were fully fenced.

He said in countries such as Botswana, Namibia, Tanzania and Zimbabwe, wild areas were partially fenced or not fenced at all. Animals were free to roam in conservancies, owned by communities who benefited directly from hunting quotas.

‘Not my problem’

“Human-wildlife conflict is huge, but tolerance is higher because they see the benefits. In South Africa, because of the fences, tolerance is very low when (damage-causing) animals come out.” People often felt a sense of exclusion from park — and so whatever happened in a park was “really not my problem; it does not really affect me”, said Tshabalala.

Vusi Tshabalala, an avid conservation champion, reckons that young people who live on the fringes of the Kruger National Park should be benefitting more from protecting wildlife, but sadly, many have turned to poaching for a wide mix of reasons, including the simple need for bushmeat which, he says, should be become more readily available through legal channels. (Photo: © WWF | Warren Ngobeni | Wild Shots Outreach)

Drawing on his work with 86 communities and 42 different conservation projects in the Greater Kruger area, he spoke about how many people enjoyed no direct benefits from the park and consequently seldom reported family or neighbours who snared or hunted game.

Red tape, said Tshabalala, also made it onerous for locals to legally hunt for the pot, so instead of sustainable harvesting of wildlife which drew on indigenous knowledge and customs which contributed to conservation, we were seeing an increase in poaching and the illegal wildlife trade, he said.

Responding to a question from the floor, Inglis put it to the panel that the existing legal framework and government policy on wildlife ownership was perhaps biased in favour of private interests.

He spoke of a “massive uptick in snaring and poaching around national parks” as the economy slumped in the wake of Covid, “with people simply trying to survive, to eke out a living”.

In the face of rising unemployment, Rademeyer called for the creation of a wildlife economy that would allow more people to benefit. “Conservation and wild spaces are increasingly under pressure and they don’t exist without people.”

Building relationships

Tshabalala stressed that along with addressing issues of ownership of wildlife we needed to build a sense of responsibility. And he wanted to see more effort and more investment into building relationships — something that would not be achieved with laws.

Rall felt we should look beyond laws and treaties and instead seek environmental justice. This included balancing the law with the needs of the people who live with the consequences of laws, while at the same time being more respectful of indigenous knowledge systems and cultural differences.

She also felt that much media reporting on wildlife crime added to the problem. It tended to focus narrowly on poachers, criminalised communities living on the boundaries of parks while ignoring the many complexities at play. This was counterproductive to the efforts of community conservation initiatives by South African National Parks and others, she said.

In this regard, Rall and Inglis shared a few details about the Khetha 2024 Story Project.

Emerging writer Buntu Duku of Kruger2Canyon News (left) and Harriet Nimo of Wild Shots Outreach had engaging discussions at the recent launch of the Khetha 2024 Journalism Project in Hoedspruit. (Photo: © WWF | Karabo Magakane)

It involves investing in seasoned and up-and-coming journalists to encourage storytelling and making space for diverse perspectives, especially the voices of people directly affected by wildlife crime.

The thinking is that by changing perceptions and creating a deeper understanding of the complexities of wildlife crime, we could better inform approaches to address it, said Rall.

The project, designed by Roving Reporters and Jive Media Africa, includes a series of webinars which shall provide opportunities for seasoned journalists to apply for Khetha story grants. The story grants aim to assist South African and international journalists in reporting on wildlife crimes and conservation challenges in the Greater Kruger area through access to local, on-the-ground knowledge.

Rookie reporters, early career scientists and conservation enthusiasts worldwide are also invited to take part in the Khetha 2024 Story Project by joining Roving Reporters’ New Narratives ’24 team.

For further information contact esther@jivemedia.co.za. DM

Additional reporting by Matthew Hattingh.

Maxcine Kater is an environmental officer at the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment and a representative of Roving Reporters New Narratives ’24 team.

This story was produced with the support of Jive Media Africa, science communication partner to Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 66797

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: WILDLIFE CRIME/TRADE/BREEDING

Trading in wild things: Major rethink required, for biodiversity’s sake

An international shortage of lab monkeys is driving prices higher, with concerns that this is fuelling the hidden market. (Photo: Nature Needs More)

By Don Pinnock | 12 Feb 2024

Every year, millions of creatures and plants are traded for food, pets, fashion, curios and traditional medicines. Some end up as hunting trophies. There’s a mechanism to regulate this, but it isn’t working. The problem has a fix, but it will take audacity.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Peering through rimless glasses and flipping pages, gold cufflinks flashing, Judge Alfred Cockrell is going through documents in forensic detail as befits his role.

He has a gentle, almost fatherly smile as he demands precision from a bench of black-clad advocates in the Cape Town High Court seeking to contest hunting quotas for lions, rhinos, elephants and leopards.

The case before him is about the procedures around trophy hunting permits granted or not granted by Barbara Creecy, Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment.

The legal contest, brought by the Humane Society International/Africa, is ultimately dismissed, though certain costs of the no doubt considerably expensive case must, rules the judge, be shared.

Within a day of intense argument, however, there is a sub-theme on which, unfortunately, the judge feels he cannot comment as it would be overreach in terms of the case: how to evaluate the threat to a species by human action; a so-called non-detriment finding (NDF). How can that be assessed, who requires it and is it even possible?

Before we take a step in that direction, let’s do a bit of acronym bush clearing, because the names of the organisations coming up are a mouthful. There’s CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), Nemba (the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act, 2004) and the Scientific Authority of South Africa.

While we’re at it, keep in mind another bit of shorthand: Appendix 1, 2 and 3 are categories CITES uses to afford different levels of protection to wild species – 1 being the highest, where species are threatened with extinction and need the most protection. Then there’s reverse listing, but we’ll come to that later.

To export for trade a species listed under Appendix 1 or 2, CITES requires the Scientific Authority to provide an NDF in terms of Nemba requirements. Thank heavens for acronyms, or that would’ve been a very long sentence.

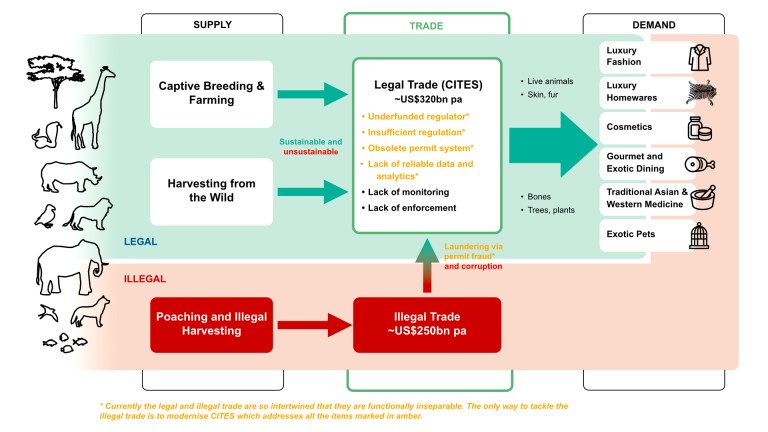

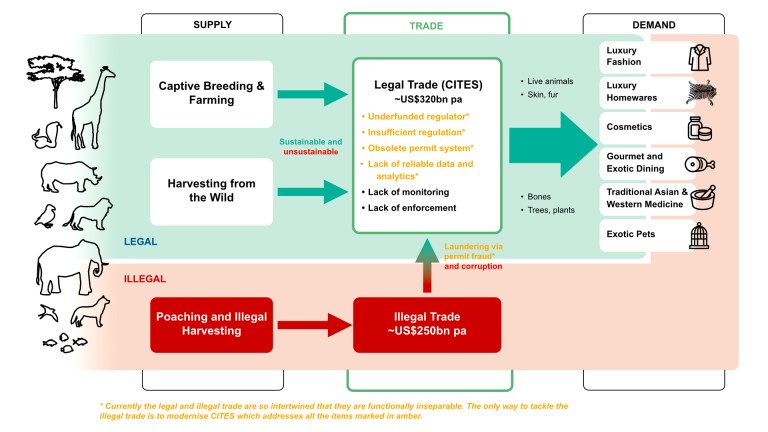

Trade in wildlife. (Graphic: Nature Needs More)

It seems reasonable: before issuing an export permit, the scientific authority of a country has to ensure the trade doesn’t endanger the species’ population or disrupt its role in the ecosystem. It’s what scientists are for, right? But before we move on, let’s unpack what that requirement entails.

To ensure no harm will be done to a species, you need to know (take a deep breath) its biology and life-history characteristics; its range (historical and current); population structure, status and trends (in the harvested area, nationally and internationally); threats; historical and current species-specific levels and patterns of harvest and mortality (like age and sex); management measures currently in place and proposed, including adaptive management strategies and consideration of levels of compliance; population monitoring and conservation status. (Check out these requirements.)

How do we know what is detrimental?

All 184 CITES members are required to do an NDF on exports, but undertaking all that is, as you can imagine, time-consuming and expensive, and requires people who know how to do it.

This doesn’t mean it can’t be done, just that confidence in exporting countries – mainly in the Global South – actually doing it before issuing an export permit is not high. Without it, or it not having been done properly, an entire species can be placed at risk.

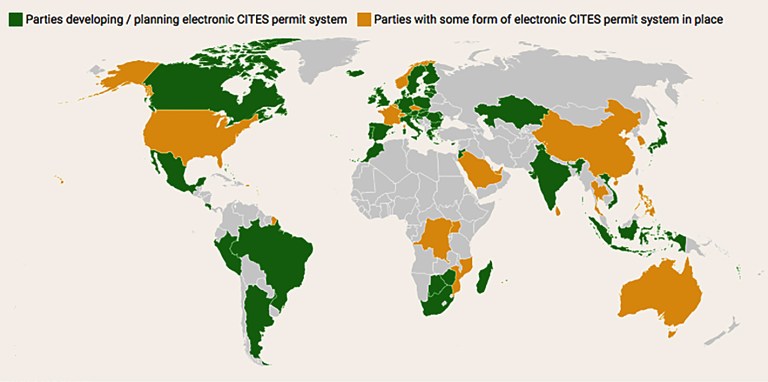

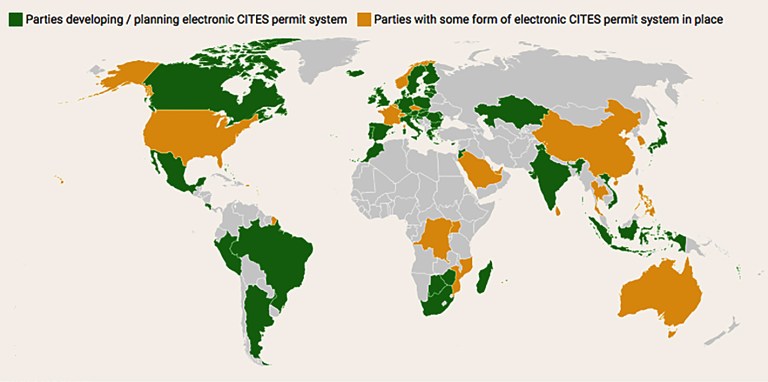

Countries with and without electronic listing of export permits. (Map: Nature Needs More)

Indeed, there are holes all over the place, according to a report by Nature Needs More, entitled “You can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear”.

For a start, most traded species are simply not listed by CITES and are being traded without regulation.

Then, for Appendix 2 species (being the majority of all CITES-listed species), while exporting them requires an NDF, it is essentially “non-binding” in that there’s no penalty for ignoring it.

CITES is aware that NDFs are not doing a decent job.

A 2020 Secretariat report on NDFs was a damning indictment of the lack of quality in NDFs, finding that 64% of those surveyed inadequately considered the precautionary principle and 83% did not fully consider patterns of harvest and mortality.

It gets worse.

A peer-reviewed study published in the Journal of Environmental Management, entitled “Determining the sustainability of legal wildlife management”, found that, for most species, there was no accurate data to estimate wild population sizes, population abundance or volumes collected or traded.

So how do you answer the most basic question on which to base an NDF: what is a sustainable offtake? You can’t.

“When combined with a lack of political will,” the study notes, “this often results in scientific and economic uncertainties being propagated through most national to international trade.”

It found that in many developing countries, there was a great tendency to miscalculate what is sustainable.

The international commercial trade in at least 267 amphibian species is not regulated by CITES even though some of these species are considered threatened. (Photo: Nature Needs More)

In the wildlife field, “sustainable” has become an irritating buzzword. What it should mean is that use for human needs should not lead to a decline in biodiversity. But it’s a term as misused as “free-range” eggs. It’s a feel-good tag to make a product or action smell green and leafy.

True sustainability is damnably hard to measure but is critical to an NDF finding.

And can you calculate unintended consequences? In the 1970s/80s, for example, the trade in frogs’ legs from India and Bangladesh saw a boom in the agricultural pests they ate and an upsurge in the use of pesticides. How wide are the boundaries of your assessment? It matters.

Trade and more trade

The disturbing truth is that not only are we unaware of what’s being poached and trafficked, we don’t even know the volumes of legal trade and whether it’s sustainable.

That’s because most trade in wild species occurs outside the CITES system. To be “inside”, it has to be listed as one of the 40,900 among the earth’s estimated 8,7 million species.

Take songbirds, much desired for their sweet singing in lonely cages by people unaware of the cruelty being perpetrated. Of the estimated 6,659 traded species, none is listed in the CITES database.

Of the 36% of reptiles traded, only 9% are listed there.

Of the 17% of amphibians traded, only 2.4% are listed.

Sea cucumbers are essential for the healthy functioning of marine ecosystems, but population reductions have a knock-on effect on food webs. (Photo: Nature Needs More)

The rarer they are, the harder they get hammered. It doesn’t mean all these species are under threat, it’s that we just don’t know. It is largely a free-for-all.

The truth is that a CITES listing does not necessarily stop or even detect unsustainable trade.

While quotas and export permits may claim to be legal and transparent in claiming a sustainable trade, in the absence of solid NDFs they may be as sustainable as draining a pond to save the fish.

To be listed for trade, a country has to formally request its inclusion. Why would it do that? Largely because the species is considered potentially at risk, which is why it ended up with an Appendix listing in the first place, meaning it’s potentially in trouble.

But waiting for species to become vulnerable to extinction before providing safeguards is too high a risk.

Okay, where are we?

Apart from non-listing, let’s tick off NDF problems.

They’re complicated, potentially expensive and liable to be badly done (between 2003 and 2012, CITES exports from Africa had documentation discrepancies in 92% of records).

There’s no mechanism to control their quality and they may take so long that a species could be almost beyond saving before they’re implemented.

Worst of all, they might simply not be undertaken, which means they’re not done for the majority of species exported.

The truth is that the entire CITES export mechanism, which was designed in the 1960s, is no longer fit for purpose.

How do we fix it?

The solution is a no-brainer. No wild species, listed or not, should be traded unless permitted by an NDF. It’s called reverse listing.

The details of this have been finely worked out by trade specialist Dr Lynn Johnson of Nature Needs More.

The problem, says Johnson, is that when a risk is perceived, it’s up to the exporting country to make the call by way of an NDF. By reverse listing, it would be up to importing countries or companies to ensure – and pay the exporting country for – an NDF permitting their use of the species.

She points out that most legal and laundered illegal trade is overwhelmingly for luxury products produced and sold in a handful of wealthy countries, mainly the US, EU, China, Japan and the UK.

These businesses should pay for and ensure the legality of their supply chains and for the NDFs required to do this.

A new Appendix 1, she suggests, could be created for species afforded the highest level of protection, forbidding all movement across international borders for trade, educational or scientific purposes. This would cover animals with high levels of sentience, like elephants, primates or cetaceans such as dolphins and orcas.

A new Appendix 2 would work on the precautionary principle with the burden of proof on importers to prove sustainability by funding NDFs.

An import levy on CITES shipments could, in addition, be used to improve monitoring and install a global digital permit system (it is presently paper-based in most countries).

Well, why not?

It will, however, take a big shift in thinking. It’s a global problem all 184 members of CITES need to get to grips with. That won’t be easy.

CITES is a cumbersome UN-style bureaucracy with fixed traditions and many people are invested in keeping it that way.

But CITES needs a rebuild.

The danger of not changing course brings to mind a Titanic carrying the world’s precious biodiversity.

It’s time for an urgent rethink. DM

An international shortage of lab monkeys is driving prices higher, with concerns that this is fuelling the hidden market. (Photo: Nature Needs More)

By Don Pinnock | 12 Feb 2024

Every year, millions of creatures and plants are traded for food, pets, fashion, curios and traditional medicines. Some end up as hunting trophies. There’s a mechanism to regulate this, but it isn’t working. The problem has a fix, but it will take audacity.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Peering through rimless glasses and flipping pages, gold cufflinks flashing, Judge Alfred Cockrell is going through documents in forensic detail as befits his role.

He has a gentle, almost fatherly smile as he demands precision from a bench of black-clad advocates in the Cape Town High Court seeking to contest hunting quotas for lions, rhinos, elephants and leopards.

The case before him is about the procedures around trophy hunting permits granted or not granted by Barbara Creecy, Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment.

The legal contest, brought by the Humane Society International/Africa, is ultimately dismissed, though certain costs of the no doubt considerably expensive case must, rules the judge, be shared.

Within a day of intense argument, however, there is a sub-theme on which, unfortunately, the judge feels he cannot comment as it would be overreach in terms of the case: how to evaluate the threat to a species by human action; a so-called non-detriment finding (NDF). How can that be assessed, who requires it and is it even possible?

Before we take a step in that direction, let’s do a bit of acronym bush clearing, because the names of the organisations coming up are a mouthful. There’s CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), Nemba (the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act, 2004) and the Scientific Authority of South Africa.

While we’re at it, keep in mind another bit of shorthand: Appendix 1, 2 and 3 are categories CITES uses to afford different levels of protection to wild species – 1 being the highest, where species are threatened with extinction and need the most protection. Then there’s reverse listing, but we’ll come to that later.

To export for trade a species listed under Appendix 1 or 2, CITES requires the Scientific Authority to provide an NDF in terms of Nemba requirements. Thank heavens for acronyms, or that would’ve been a very long sentence.

Trade in wildlife. (Graphic: Nature Needs More)

It seems reasonable: before issuing an export permit, the scientific authority of a country has to ensure the trade doesn’t endanger the species’ population or disrupt its role in the ecosystem. It’s what scientists are for, right? But before we move on, let’s unpack what that requirement entails.

To ensure no harm will be done to a species, you need to know (take a deep breath) its biology and life-history characteristics; its range (historical and current); population structure, status and trends (in the harvested area, nationally and internationally); threats; historical and current species-specific levels and patterns of harvest and mortality (like age and sex); management measures currently in place and proposed, including adaptive management strategies and consideration of levels of compliance; population monitoring and conservation status. (Check out these requirements.)

How do we know what is detrimental?

All 184 CITES members are required to do an NDF on exports, but undertaking all that is, as you can imagine, time-consuming and expensive, and requires people who know how to do it.

This doesn’t mean it can’t be done, just that confidence in exporting countries – mainly in the Global South – actually doing it before issuing an export permit is not high. Without it, or it not having been done properly, an entire species can be placed at risk.

Countries with and without electronic listing of export permits. (Map: Nature Needs More)

Indeed, there are holes all over the place, according to a report by Nature Needs More, entitled “You can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear”.

For a start, most traded species are simply not listed by CITES and are being traded without regulation.

Then, for Appendix 2 species (being the majority of all CITES-listed species), while exporting them requires an NDF, it is essentially “non-binding” in that there’s no penalty for ignoring it.

CITES is aware that NDFs are not doing a decent job.

A 2020 Secretariat report on NDFs was a damning indictment of the lack of quality in NDFs, finding that 64% of those surveyed inadequately considered the precautionary principle and 83% did not fully consider patterns of harvest and mortality.

It gets worse.

A peer-reviewed study published in the Journal of Environmental Management, entitled “Determining the sustainability of legal wildlife management”, found that, for most species, there was no accurate data to estimate wild population sizes, population abundance or volumes collected or traded.

So how do you answer the most basic question on which to base an NDF: what is a sustainable offtake? You can’t.

“When combined with a lack of political will,” the study notes, “this often results in scientific and economic uncertainties being propagated through most national to international trade.”

It found that in many developing countries, there was a great tendency to miscalculate what is sustainable.

The international commercial trade in at least 267 amphibian species is not regulated by CITES even though some of these species are considered threatened. (Photo: Nature Needs More)

In the wildlife field, “sustainable” has become an irritating buzzword. What it should mean is that use for human needs should not lead to a decline in biodiversity. But it’s a term as misused as “free-range” eggs. It’s a feel-good tag to make a product or action smell green and leafy.

True sustainability is damnably hard to measure but is critical to an NDF finding.

And can you calculate unintended consequences? In the 1970s/80s, for example, the trade in frogs’ legs from India and Bangladesh saw a boom in the agricultural pests they ate and an upsurge in the use of pesticides. How wide are the boundaries of your assessment? It matters.

Trade and more trade

The disturbing truth is that not only are we unaware of what’s being poached and trafficked, we don’t even know the volumes of legal trade and whether it’s sustainable.

That’s because most trade in wild species occurs outside the CITES system. To be “inside”, it has to be listed as one of the 40,900 among the earth’s estimated 8,7 million species.

Take songbirds, much desired for their sweet singing in lonely cages by people unaware of the cruelty being perpetrated. Of the estimated 6,659 traded species, none is listed in the CITES database.

Of the 36% of reptiles traded, only 9% are listed there.

Of the 17% of amphibians traded, only 2.4% are listed.

Sea cucumbers are essential for the healthy functioning of marine ecosystems, but population reductions have a knock-on effect on food webs. (Photo: Nature Needs More)

The rarer they are, the harder they get hammered. It doesn’t mean all these species are under threat, it’s that we just don’t know. It is largely a free-for-all.

The truth is that a CITES listing does not necessarily stop or even detect unsustainable trade.

While quotas and export permits may claim to be legal and transparent in claiming a sustainable trade, in the absence of solid NDFs they may be as sustainable as draining a pond to save the fish.

To be listed for trade, a country has to formally request its inclusion. Why would it do that? Largely because the species is considered potentially at risk, which is why it ended up with an Appendix listing in the first place, meaning it’s potentially in trouble.

But waiting for species to become vulnerable to extinction before providing safeguards is too high a risk.

Okay, where are we?

Apart from non-listing, let’s tick off NDF problems.

They’re complicated, potentially expensive and liable to be badly done (between 2003 and 2012, CITES exports from Africa had documentation discrepancies in 92% of records).

There’s no mechanism to control their quality and they may take so long that a species could be almost beyond saving before they’re implemented.

Worst of all, they might simply not be undertaken, which means they’re not done for the majority of species exported.

The truth is that the entire CITES export mechanism, which was designed in the 1960s, is no longer fit for purpose.

How do we fix it?

The solution is a no-brainer. No wild species, listed or not, should be traded unless permitted by an NDF. It’s called reverse listing.

The details of this have been finely worked out by trade specialist Dr Lynn Johnson of Nature Needs More.

The problem, says Johnson, is that when a risk is perceived, it’s up to the exporting country to make the call by way of an NDF. By reverse listing, it would be up to importing countries or companies to ensure – and pay the exporting country for – an NDF permitting their use of the species.

She points out that most legal and laundered illegal trade is overwhelmingly for luxury products produced and sold in a handful of wealthy countries, mainly the US, EU, China, Japan and the UK.

These businesses should pay for and ensure the legality of their supply chains and for the NDFs required to do this.

A new Appendix 1, she suggests, could be created for species afforded the highest level of protection, forbidding all movement across international borders for trade, educational or scientific purposes. This would cover animals with high levels of sentience, like elephants, primates or cetaceans such as dolphins and orcas.

A new Appendix 2 would work on the precautionary principle with the burden of proof on importers to prove sustainability by funding NDFs.

An import levy on CITES shipments could, in addition, be used to improve monitoring and install a global digital permit system (it is presently paper-based in most countries).

Well, why not?

It will, however, take a big shift in thinking. It’s a global problem all 184 members of CITES need to get to grips with. That won’t be easy.

CITES is a cumbersome UN-style bureaucracy with fixed traditions and many people are invested in keeping it that way.

But CITES needs a rebuild.

The danger of not changing course brings to mind a Titanic carrying the world’s precious biodiversity.

It’s time for an urgent rethink. DM

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 66797

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: WILDLIFE CRIME/TRADE/BREEDING

All the big international organizations need a re-think: UN, NATO, The European Union etc. etc. They have become giants with feet of clay.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 66797

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: WILDLIFE CRIME/TRADE/BREEDING

GRAVE CONCERNS ABOUT THE MPUMALANGA PROVINCIAL AUTHORITIES ENABLING THE CRUEL, INDISCRIMINATE AND UNSCIENTIFIC MANAGEMENT OF VERVET MONKEYS

WAPFSA - 19.01.2024

The Wildlife Animal Protection Forum of South Africa (WAPFSA), a collective of thirty organisations, has a history of interest in the protection and conservation of wild animals in South Africa, sharing a body of expertise from different sectors including but not limited to scientific, environmental, legal, welfare, rights, social justice, climate, indigenous and public advocacy backgrounds.

Members of WAPFSA are also part of the Ministerial Wildlife Well-being Forum, instituted by the Department of Forestry, Fishery and the Environment (DFFE) in May 2023, by special request of Minister Barbara Creecy, in order to consult with organisations focused on best practices for the protection of wildlife.

The NEM:BA amendments came into effect on 30 June 2023. The Honourable Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment, is currently in the process of implementing a legislative mandate to prohibit activities that may have a negative impact on the well-being of wild animals and to make regulations in relation to the well-being of wild animals, as per Section 2 of NEM:BA.

In the aforementioned section of NEM:BA, it is specified that all procedural activities that constitute biodiversity management, conservation and sustainable use of wild animals, including the issuing of permits, must consider the well-being of animals.

Section 9A of NEM:BA in particular, refers to any activity where there is reasonable evidence of a potential negative impact on animal well-being, using the wording “that may have a negative impact” which means that it is not required to have absolute proof of a negative impact to prohibit any activity. It implies that a precautionary approach, in line with the NEMA principles, must prevail.

Furthermore, Section 101 refers to the fact that any failure to comply with a notice published in terms of Section 9A constitutes an offence.

Section 24 of the Constitution highlights that the environment must be protected, for the benefit of present and future generations.

In November 2023, WAPFSA submitted a formal legally motivated request to DFFE and the Minister, to include primates of South Africa as TOPS species. This request relies specifically on the lack of scientific data available about this group of species which allows for the indiscriminate killing and persecution of primates, blatantly permitted by provinces.

WAPFSA members have evidence that there is no reliable data available in relation to primate populations in any of the nine provinces.

It has come to WAPFSA’s attention that some provincial conservation agencies, including the MTPA, may be permitting the removal or even the eradication of individual or entire troops of indigenous non-human primates. In addition, the permits seem to have been issued without reliable scientific data and without adhering to best practices or carrying out sufficient due diligence, such as the assessment of the location, the proposed destination, trapping methodology or impacts on the populations or targeted individuals affected.

The WAPFSA submission to DFFE in November 2023, in relation to the TOPS regulations included a document, Annexure I, emphasising the legal requirement to add non-indigenous indigenous primates to the TOPS listing. The document also provided evidence that South Africa’s indigenous non-human primates are highly persecuted, misunderstood, indiscriminately victimised and are the objects of horrific and unjustifiable violence.

There is evidence that, although the IUCN Red List classifies the vervet monkey as Least Concern (LC), there are risks of extinction in local circumstances, when human persecution and retaliation occur.

Vervet monkeys are listed under CITES Appendix II, however provincial and national scientific authorities are failing to provide the Minister or CITES with the legally required Non-Detriment Finding. Moreover, there has been no public consultation by provincial and national authorities in relation to our indigenous primates.

There is no evidence, despite extensive research by members of WAPFSA, of verifiable data collected by any of the provinces in relation to damage or threats to humans or pets from vervet monkeys, or evidence of effective and non-violent measures to prevent human conflict with these primates.

In areas where there is the prospect of human-primate conflict, there are a number of simple precautions to take or solutions that can be implemented to reduce such conflict, such as, for example, making sure food is not visible from any windows, properly disposing of domestic waste and, if necessary, installing clear primate barriers. These simple strategies must be exhausted before considering any other option.

Often, in response to anecdotal reports or complaints linked to lifestyle considerations rather than real conflict, authorities have been known to issue very broad questionable permits to allow invasive and cruel management procedures instead of insisting upon non-lethal solutions.

Scientists advise that when vervet monkeys are “relocated”, the removal of an entire or part of a troop is highly traumatic and cruel. Members of a large troop cannot be captured simultaneously which results in some of the troop members being temporarily or permanently separated. This impacts the entire social structure of the troop.

Relocation should not be considered as an option given that primates have lived in these regions for centuries, making those landscapes and natural resources their ancestral territories. Relocation impact assessments should be carried out in advance, taking into consideration the abundance of natural foraging and green belts that these primates are accustomed too. The impacts on and from other animals should be considered as well.

When issuing permits for the relocation of vervet monkeys, does the MTPA rely on any professional assessment of the various troop dynamics in order to mitigate impacts and positively influence the behaviour of the troop? Can the MTPA kindly share,

The research on successful release, and

The mapping and characteristics of the release area;

Mapping and locations of other vervet monkey troops, near the planned release site;

Is the province issuing permits to relocate an entire vervet monkey troop as if they were allproblem animals?

The Animal Protection Act 71 of 1962 refers in Section 2 (g), to the release of so-called “vermin” and it prohibits to liberate: any animal in such manner or place as to expose it to immediate attack or danger of attack by other animals or by wild animals, or baits or provokes any animal or incites any animal to attack another animal.

Vervet monkeys are territorial mammals; just dropping a troop into unfamiliar territory is cruel and is going to put it at a great disadvantage since it will cause a conflict involving serious injuries and most probably the destruction of the new troop. Alternatively, the new troop might suddenly and chaotically split, with members becoming more vulnerable and slowly dying off.

In addition, we would like to emphasise that the province cannot set this questionable precedent without any scientific ground.

Primates are not vermin, they have a historical presence in South Africa, are part of our heritage and have cultural value. In addition, their role as seed dispersers in the conservation and regeneration of indigenous animals and plants is substantial. The important role they play particularly after fires, has been scientifically and empirically observed.

Human-induced climate change poses many potential threats and risks to nonhuman primate populations, including the ranges available to primate species. Many of these primates are already threatened by human activities such as deforestation, habitat destruction, hunting, persecution and extirpation.

Vervet monkeys are also often targeted by individual humans living in residential areas and on private estates using various weaponry or poisons. The latter is unusually cruel and can have dire consequences for untargeted wildlife and water sources. The discharge of firearms in a residential area is illegal and poses a danger to people and property.