Giving right of way to elephants

BY DON PINNOCK - 19 OCTOBER 2016 - AFRICA GEOGRAPHIC

Some cities have good bicycle lanes, some towns have excellent footpaths, but Kasane in Botswana has well-stomped elephant corridors. Of course they’re also used by warthogs, impala and any other wild animals that need to amble down to the Chobe River for a drink.

BY DON PINNOCK - 19 OCTOBER 2016 - AFRICA GEOGRAPHIC

Some cities have good bicycle lanes, some towns have excellent footpaths, but Kasane in Botswana has well-stomped elephant corridors. Of course they’re also used by warthogs, impala and any other wild animals that need to amble down to the Chobe River for a drink.

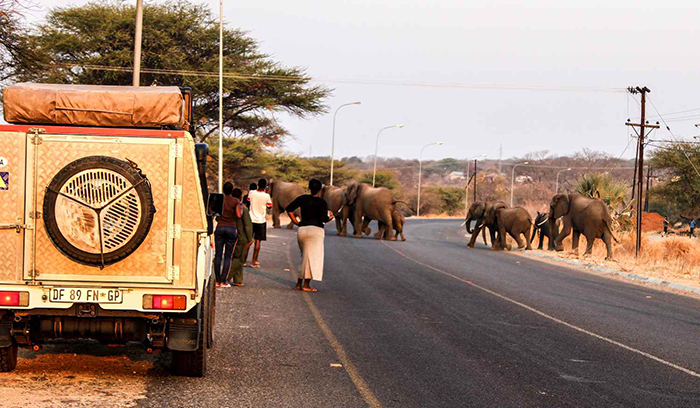

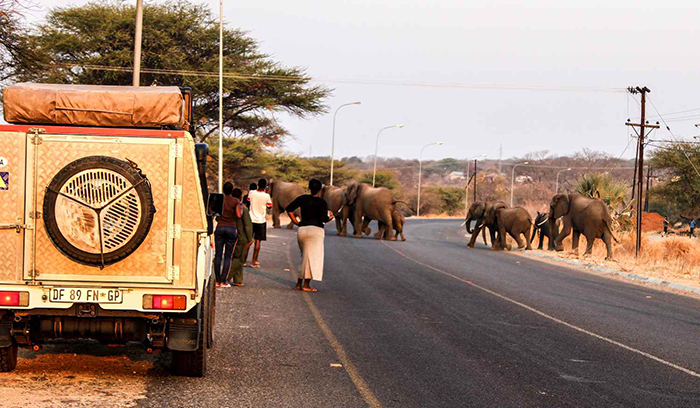

It’s not uncommon to see traffic on the town’s main road backed up as a family of tuskers plod unconcernedly across the tarmac. If a lion pride happens to be on the prowl or the weather is inclement, warthogs take refuge in the town’s culverts.

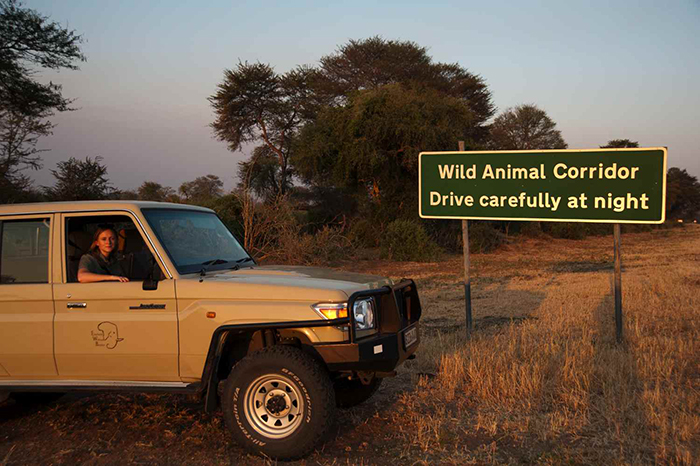

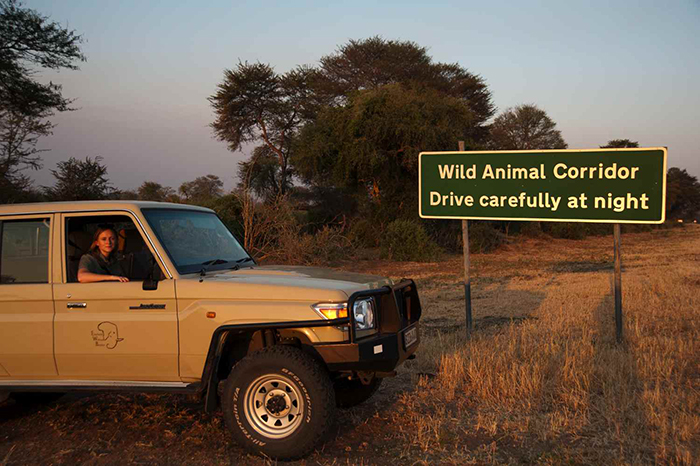

Of course some locals – who don’t seem to realise that Kasane’s existence depends on the surrounding Chobe National Park – don’t approve of the wild traffic. But an NGO appropriately called Elephants Without Borders (EWB), is holding firm. For many years it has been fighting for the sanctity of the corridors and putting up warning signs in case visitors get spooked or have the temerity to hoot.

“If we want to maintain our environment in the future, we have to work out how people and wildlife can co-exist.” said Tempe Adams, who’s been monitoring the corridors for EWB. “That’s true for small areas like Kasane, entire countries and transnational migration routes.”

Right then we were sitting in her vehicle watching elephants peacefully munching mopane leaves next to a quarry. Later we paused to let a large cow and her floppy-trunked calf cross the road to an area called The Seep, which appeared to be an evening gathering spot for tuskers, slurping water and throwing sand over their shoulders.

People were fishing in the river, their backs turned towards the elephants not 50 metres behind them and some mango-tree mechanics had their heads under a jalopy bonnet, ignoring the large wild creatures plodding past them.

People from Kasane must be among the most chilled in the world about having wildlife around them. In a survey Tempe did among Botswana residents, 90% said they liked seeing elephants and one in three went so far as to they loved and appreciated them in the natural world.

There were some (11%) – ‘probably outsiders’ according to Tempe – who didn’t like elephants and said they posed a danger and caused damage. Those who liked them around listed their reasons, including the wildlife being a national heritage, interesting, aesthetically pleasing, good for tourism and because they were ‘here first.’

“Most responses were really interesting,” said Tempe. “They said they enjoyed seeing elephants. When I asked them why, they told me they could relate to them because they lived in families like us, were here before people and belonged to the ecosystem.”

However, the large number of elephants in Botswana did worry respondents, who said this needed to be managed. This is an increasing problem for the country which is becoming an ‘elephant refuge’ as massive poaching in neighbouring states dives the animals into areas of greatest protection.

Kasane corridors are a microcosm of a much greater issue related to migratory corridors within and between countries in the Southern and Central African region. One of the main goals of the Kavango Zambezi Conservation Area development (KAZA) which was established between Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Angola and Botswana, was to facilitate and protect these corridors. But with poaching and problematic cooperation between its member countries, it is failing to do this. The result has been a steady migration of elephants into Botswana, where they are well protected by the Botswana Defense Force.

The results of EWB’s just-released Great Elephant Survey are a wake-up call. Elephant numbers in all but a few Southern African states are declining, some alarmingly. In Tanzania the population has crashed by 60% in five years, in Mozambique by 53% over the same period. The survey found that between 2010 and 2014, savanna elephants died at the rate of one every two hours. The population now stands at an estimated 363,057, a drop over eight years of 144,000. With this decline, the areas surveyed will lose half their elephant population every nine years. Elephant deaths are exceeding the birthrate.

Human population increase in Africa is also causing fragmentation of wildlife habitats and increasing conflict with rural and urban communities. “We need to know where wildlife is moving, and where likely conflict points will be,” said Tempe. “As armed struggle recedes, people are moving towards resources such as rivers and nutrient-rich soils which are used by wildlife. And in urban areas such as Kasane populations are growing.”

Elephants seem equally keen to avoid confrontations. Along the Chobe River they avoid daily traffic times, restricting road crossings to night journeys. Acknowledged corridors and human willingness to share space with wild animals are key principles towards which Elephants Without Borders has been working for many years. In Kasane – and in much of Botswana – people seem to understand that elephants are a far older species that we.

We are people in an over-peopled planet but are, in truth, the strangers in their strange land. In terms of biological seniority, they deserve the right of way. For more information on this topic, a research paper on Kasane corridors can be found

here!