I don't think that it will happen in Brazil while Bolsanero is in power

Illegal Logging and Deforestation in Africa.

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65934

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Illegal Logging and Deforestation in Africa.

So Right

I don't think that it will happen in Brazil while Bolsanero is in power

I don't think that it will happen in Brazil while Bolsanero is in power

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65934

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Illegal Logging and Deforestation in Africa.

When tree planting actually damages ecosystems

July 26, 2019 2.20pm BST

Kate Parr

Professor of Tropical Ecology, University of Liverpool

Caroline Lehmann

Senior Lecturer in Biogeography, University of Edinburgh

Tree planting has been widely promoted as a solution to climate change, because plants absorb the climate-warming gases from Earth’s atmosphere as they grow. World leaders have already committed to restoring 350m hectares of forest by 2030 and a recent report suggested that reforesting a billion hectares of land could store a massive 205 gigatonnes of carbon – two thirds of all the carbon released into the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution.

Many of those trees could be planted in tropical grassy biomes according to the report. These are the savannas and grasslands that cover large swathes of the globe and have a grassy ground layer and variable tree cover. Like forests, these ecosystems play a major role in the global carbon balance. Studies have estimated that grasslands store up to 30% of the world’s carbon that’s tied up in soil. Covering 20% of Earth’s land surface, they contain huge reserves of biodiversity, comparable in areas to tropical forest. These are the landscapes with lions, elephants and vast herds of wildebeest.

Gorongosa, Mozambique. The habitat here is open, well-lit and with few trees. Caroline Lehmann, Author provided

Savannas and grasslands are home to nearly one billion people, many of whom raise livestock and grow crops. Tropical grassy biomes were the cradle of humankind – where modern humans first evolved – and they are where important food crops such as millet and sorghum originated, which millions eat today. And, yet among the usual threats of climate change and wildlife habitat loss, these ecosystems face a new threat – tree planting.

It might sound like a good idea, but planting trees here would be damaging. Unlike forests, ecosystems in the tropics that are dominated by grass can be degraded not only by losing trees, but by gaining them too.

Where more trees isn’t the answer

Increasing the tree cover in savanna and grassland can mean plant and animal species which prefer open, well-lit environments are pushed out. Studies from South Africa, Australia and Brazil indicate that unique biodiversity is lost as tree cover increases.

This is because adding trees can alter how these grassy ecosystems function. More trees means fires are less likely, but regular fire removes vegetation that shades ground layer plants. Not only do herbivores like zebra and antelope that feed on grass have less to eat, but more trees may also increase their risk of being eaten as predators have more cover.

A mosaic of grassland and forest in Gabon. Kate Parr, Author provided

More trees can also reduce the amount of water in streams and rivers. As a result of humans suppressing wildfires in the Brazilian savannas, tree cover increased and the amount of rain reaching the ground shrank. One study found that in grasslands, shrublands and cropland worldwide where forests were created, streams shrank by 52% and 13% of all streams dried up completely for at least a year.

Grassy ecosystems in the tropics provide surface water for people to drink and grazing land for their livestock, not to mention fuel, food, building materials and medicinal plants. Tree planting here could harm the livelihoods of millions.

Losing ancient grassy ecosystems to forests won’t necessarily be a net benefit to the climate either. Landscapes covered by forest tend to be darker in colour than savanna and grassland, which might mean they also absorb more heat. As drought and wildfires become more frequent, grasslands may be a more reliable carbon sink than forests.

Redefine forests

How have we reached the point where the unique tropical savannas and grasslands of the world are viewed as suitable for wholesale “restoration” as forests?

At the root of the problem is that these grassy ecosystems are fundamentally misunderstood. The Food and Agricultural Organisation of the UN defines any area that’s half a hectare in size with more than 10% tree cover as forest. This assumes that landscapes like an African savanna are degraded because they have fewer trees and so need to be reforested. The grassy ground layer houses a unique range of species, but the assumption that forests are more important threatens grassy ecosystems across the tropics and beyond, including in Madagascar, India and Brazil.

A flowering aloe in Madagascan grassland. Caroline Lehmann, Author provided

“Forest” should be redefined to ensure savannas and grasslands are recognised as important systems in their own right, with their own irreplaceable benefits to people and other species. It’s essential people know what degradation looks like in open, sunlit ecosystems with fewer trees, so as to restore ecosystems that are actually degraded with more sensitivity.

Calls for global tree planting programmes to cool the climate need to think carefully about the real implications for all of Earth’s ecosystems. The right trees need to be planted in the right places. Otherwise, we risk a situation where we miss the savanna for the trees, and these ancient grassy ecosystems are lost forever.

July 26, 2019 2.20pm BST

Kate Parr

Professor of Tropical Ecology, University of Liverpool

Caroline Lehmann

Senior Lecturer in Biogeography, University of Edinburgh

Tree planting has been widely promoted as a solution to climate change, because plants absorb the climate-warming gases from Earth’s atmosphere as they grow. World leaders have already committed to restoring 350m hectares of forest by 2030 and a recent report suggested that reforesting a billion hectares of land could store a massive 205 gigatonnes of carbon – two thirds of all the carbon released into the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution.

Many of those trees could be planted in tropical grassy biomes according to the report. These are the savannas and grasslands that cover large swathes of the globe and have a grassy ground layer and variable tree cover. Like forests, these ecosystems play a major role in the global carbon balance. Studies have estimated that grasslands store up to 30% of the world’s carbon that’s tied up in soil. Covering 20% of Earth’s land surface, they contain huge reserves of biodiversity, comparable in areas to tropical forest. These are the landscapes with lions, elephants and vast herds of wildebeest.

Gorongosa, Mozambique. The habitat here is open, well-lit and with few trees. Caroline Lehmann, Author provided

Savannas and grasslands are home to nearly one billion people, many of whom raise livestock and grow crops. Tropical grassy biomes were the cradle of humankind – where modern humans first evolved – and they are where important food crops such as millet and sorghum originated, which millions eat today. And, yet among the usual threats of climate change and wildlife habitat loss, these ecosystems face a new threat – tree planting.

It might sound like a good idea, but planting trees here would be damaging. Unlike forests, ecosystems in the tropics that are dominated by grass can be degraded not only by losing trees, but by gaining them too.

Where more trees isn’t the answer

Increasing the tree cover in savanna and grassland can mean plant and animal species which prefer open, well-lit environments are pushed out. Studies from South Africa, Australia and Brazil indicate that unique biodiversity is lost as tree cover increases.

This is because adding trees can alter how these grassy ecosystems function. More trees means fires are less likely, but regular fire removes vegetation that shades ground layer plants. Not only do herbivores like zebra and antelope that feed on grass have less to eat, but more trees may also increase their risk of being eaten as predators have more cover.

A mosaic of grassland and forest in Gabon. Kate Parr, Author provided

More trees can also reduce the amount of water in streams and rivers. As a result of humans suppressing wildfires in the Brazilian savannas, tree cover increased and the amount of rain reaching the ground shrank. One study found that in grasslands, shrublands and cropland worldwide where forests were created, streams shrank by 52% and 13% of all streams dried up completely for at least a year.

Grassy ecosystems in the tropics provide surface water for people to drink and grazing land for their livestock, not to mention fuel, food, building materials and medicinal plants. Tree planting here could harm the livelihoods of millions.

Losing ancient grassy ecosystems to forests won’t necessarily be a net benefit to the climate either. Landscapes covered by forest tend to be darker in colour than savanna and grassland, which might mean they also absorb more heat. As drought and wildfires become more frequent, grasslands may be a more reliable carbon sink than forests.

Redefine forests

How have we reached the point where the unique tropical savannas and grasslands of the world are viewed as suitable for wholesale “restoration” as forests?

At the root of the problem is that these grassy ecosystems are fundamentally misunderstood. The Food and Agricultural Organisation of the UN defines any area that’s half a hectare in size with more than 10% tree cover as forest. This assumes that landscapes like an African savanna are degraded because they have fewer trees and so need to be reforested. The grassy ground layer houses a unique range of species, but the assumption that forests are more important threatens grassy ecosystems across the tropics and beyond, including in Madagascar, India and Brazil.

A flowering aloe in Madagascan grassland. Caroline Lehmann, Author provided

“Forest” should be redefined to ensure savannas and grasslands are recognised as important systems in their own right, with their own irreplaceable benefits to people and other species. It’s essential people know what degradation looks like in open, sunlit ecosystems with fewer trees, so as to restore ecosystems that are actually degraded with more sensitivity.

Calls for global tree planting programmes to cool the climate need to think carefully about the real implications for all of Earth’s ecosystems. The right trees need to be planted in the right places. Otherwise, we risk a situation where we miss the savanna for the trees, and these ancient grassy ecosystems are lost forever.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65934

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Illegal Logging and Deforestation in Africa.

I might be wrong, but I have never heard that someone wants to plant trees in the Savanna, only where the trees have been cut previously

Reading the article, obviously someone has had the idea, but to me, it sounds rather strange. For heaven's sake don't interfere with nature where you have not put hands before!!

Reading the article, obviously someone has had the idea, but to me, it sounds rather strange. For heaven's sake don't interfere with nature where you have not put hands before!!

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65934

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Illegal Logging and Deforestation in Africa.

High-value opportunities exist to restore tropical rainforests around the world – here’s how we mapped them

July 3, 2019 7.07pm BST Updated July 5, 2019 4.59pm BST

Robin Chazdon

Professor Emerita of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut

The green belt of tropical rainforests that covers equatorial regions of the Americas, Africa, Indonesia and Southeast Asia is turning brown. Since 1990, Indonesia has lost 50% of its original forest, the Amazon 30% and Central Africa 14%. Fires, logging, hunting, road building and fragmentation have heavily damaged more than 30% of those that remain.

These forests provide many benefits: They store large amounts of carbon, are home to numerous wild species, provide food and fuel for local people, purify water supplies and improve air quality. Replenishing them is an urgent global imperative. A newly published study in the journal Science by European authors finds that there is room for an extra 3.4 million square miles (0.9 billion hectares) of canopy cover around the world, and that replenishing tree cover at this full potential would contribute significantly to reducing the risk of harmful climate change

But there aren’t enough resources to restore all tropical forests that have been lost or damaged. And restoration can conflict with other activities, such as farming and forestry. As a tropical forest ecologist, I am interested in developing better tools for assessing where these efforts will be most cost-effective and beneficial.

Over the past four years, tropical forestry professor Pedro Brancalion and I have led a team of researchers from an international network in evaluating the benefits and feasibility of restoration across tropical rainforests around the world. Our newly published findings identify restoration hotspots – areas where restoring tropical forests would be most beneficial and least costly and risky. They cover over 385,000 square miles (100 million hectares), an area as large as Spain and Sweden combined.

The five countries with the largest areas of restoration hotpots are Brazil, Indonesia, India, Madagascar and Colombia. Six countries in Africa – Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi, Togo, South Sudan and Madagascar – hold rainforest areas where restoration is expected to yield the highest benefits with the highest feasibility. We hope our results can help governments, conservation groups and international funders target areas where there is high potential for success.

A native tree nursery for large-scale restoration of Atlantic Forest at Reserva Natural Guapiaçu, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Robin Chazdon, CC BY-ND

Where to start

Intact forest landscapes in tropical regions declined by 7.2% from 2000 to 2013, mainly due to logging, clearing and fires. These losses have dire consequences for global biodiversity, climate change and forest-dependent peoples.

As my work has shown, tropical forests can recover after they have been cleared or damaged. Although these second-growth forests will never perfectly replace the older forests that have been lost, planting carefully selected trees and assisting natural recovery processes can restore many of their former properties and functions.

But restoration is not uniformly feasible or desirable, and the benefits that forests provide are not evenly distributed. To make informed choices about restoration efforts and investments, organizations need more detailed spatial information. Existing global maps of restoration opportunities are based on actual versus potential levels of tree canopy cover. We wanted to go beyond this measurement to identify where the greatest potential payoffs and challenges lay.

Our study used high-resolution satellite imagery and the latest peer-reviewed research to integrate information about four benefits from forest restoration: biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation and water security. We also assessed three aspects of feasibility: cost, investment risk and the likelihood of restored forests surviving into the future.

We studied these variables across all lowland tropical moist forests worldwide, dividing them into 1-kilometer square blocks that had lost more than 10% of their tree canopy cover in 2016. Each of the seven factors we studied had equal weight in our calculation of total restoration opportunity scores.

The top-scoring blocks, which we call “restoration hotspots,” represent the most compelling regions for tropical forest restoration, with maximum overall benefits and minimal negative trade-offs.

https://youtu.be/b-U77ZgVOsg

Forest restoration involves much more than planting trees.

Forest restoration aligns with other global pledges

The top 15 countries with the largest areas of restoration hotspots are distributed across all tropical rainforest regions around the world. Three are in Central and South America, five are in Africa and the Middle East, and seven are in Asia and the Pacific.

Importantly, 89% of the hotspots we identified were located within areas that have already been identified as biodiversity conservation hotspots in tropical regions. These conservation hotspots have exceptionally high concentrations of at-risk species. They have been been focal areas for investment and activities to promote biodiversity conservation for nearly 20 years.

This finding makes sense, since two criteria for designating conservation hotspots – high rates of forest loss and high concentration of endemic, or locally distributed, species – were also variables in our study. Our results strongly support the need to develop and implement integrated solutions that protect remaining forest ecosystems and restore new forests within these high-priority regions.

We also found that 73% of tropical forest restoration hotspots are in countries that have made commitments under the Bonn Challenge, a global effort to bring some 580,000 square miles (150 million hectares) of the world’s deforested and damaged land into restoration by 2020, and 1.35 million square miles (350 million hectares) by 2030. By making these pledges, Bonn Challenge participants have shown that they are politically motivated to restore and conserve forests, and are looking for restoration opportunities.

Forest restoration on small farms bordering Mpanga Forest Reserve, Uganda, can bring high levels of benefits and is relatively feasible to achieve. Robin Chazdon, CC BY-ND

A means toward many ends

The 88% of the lands we analyzed that did not qualify as restoration hotspots also deserve careful attention. These landscapes could be prioritized for restoration interventions that increase food, water and fuel security through agroforestry practices, watershed protection, woodlots for producing firewood and local timber or commercial tree plantations. All of these areas can provide benefits for people and the environment through combinations of different restoration approaches, even if they are not the best candidates for a full-scale effort to restore a high-functioning forest.

Forest restoration is also urgently needed in other types of forests across the world, such as seasonally dry tropical forests and temperate forests that are heavily managed for timber. Identifying key restoration opportunities in these regions requires separate studies based on their unique benefits and challenges.

Our study helps to highlight how restoring tropical forests can provide multiple benefits for people and nature, and aligns with existing conservation and sustainable development agendas, as discussed in a newly published perspective related to the new findings in Science. We hope that our map of restoration opportunities and hotspots will provide useful guidance for nations, conservation organizations and funders, and that local communities and organizations will be engaged in and benefit from these efforts.

July 3, 2019 7.07pm BST Updated July 5, 2019 4.59pm BST

Robin Chazdon

Professor Emerita of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut

The green belt of tropical rainforests that covers equatorial regions of the Americas, Africa, Indonesia and Southeast Asia is turning brown. Since 1990, Indonesia has lost 50% of its original forest, the Amazon 30% and Central Africa 14%. Fires, logging, hunting, road building and fragmentation have heavily damaged more than 30% of those that remain.

These forests provide many benefits: They store large amounts of carbon, are home to numerous wild species, provide food and fuel for local people, purify water supplies and improve air quality. Replenishing them is an urgent global imperative. A newly published study in the journal Science by European authors finds that there is room for an extra 3.4 million square miles (0.9 billion hectares) of canopy cover around the world, and that replenishing tree cover at this full potential would contribute significantly to reducing the risk of harmful climate change

But there aren’t enough resources to restore all tropical forests that have been lost or damaged. And restoration can conflict with other activities, such as farming and forestry. As a tropical forest ecologist, I am interested in developing better tools for assessing where these efforts will be most cost-effective and beneficial.

Over the past four years, tropical forestry professor Pedro Brancalion and I have led a team of researchers from an international network in evaluating the benefits and feasibility of restoration across tropical rainforests around the world. Our newly published findings identify restoration hotspots – areas where restoring tropical forests would be most beneficial and least costly and risky. They cover over 385,000 square miles (100 million hectares), an area as large as Spain and Sweden combined.

The five countries with the largest areas of restoration hotpots are Brazil, Indonesia, India, Madagascar and Colombia. Six countries in Africa – Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi, Togo, South Sudan and Madagascar – hold rainforest areas where restoration is expected to yield the highest benefits with the highest feasibility. We hope our results can help governments, conservation groups and international funders target areas where there is high potential for success.

A native tree nursery for large-scale restoration of Atlantic Forest at Reserva Natural Guapiaçu, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Robin Chazdon, CC BY-ND

Where to start

Intact forest landscapes in tropical regions declined by 7.2% from 2000 to 2013, mainly due to logging, clearing and fires. These losses have dire consequences for global biodiversity, climate change and forest-dependent peoples.

As my work has shown, tropical forests can recover after they have been cleared or damaged. Although these second-growth forests will never perfectly replace the older forests that have been lost, planting carefully selected trees and assisting natural recovery processes can restore many of their former properties and functions.

But restoration is not uniformly feasible or desirable, and the benefits that forests provide are not evenly distributed. To make informed choices about restoration efforts and investments, organizations need more detailed spatial information. Existing global maps of restoration opportunities are based on actual versus potential levels of tree canopy cover. We wanted to go beyond this measurement to identify where the greatest potential payoffs and challenges lay.

Our study used high-resolution satellite imagery and the latest peer-reviewed research to integrate information about four benefits from forest restoration: biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation and water security. We also assessed three aspects of feasibility: cost, investment risk and the likelihood of restored forests surviving into the future.

We studied these variables across all lowland tropical moist forests worldwide, dividing them into 1-kilometer square blocks that had lost more than 10% of their tree canopy cover in 2016. Each of the seven factors we studied had equal weight in our calculation of total restoration opportunity scores.

The top-scoring blocks, which we call “restoration hotspots,” represent the most compelling regions for tropical forest restoration, with maximum overall benefits and minimal negative trade-offs.

https://youtu.be/b-U77ZgVOsg

Forest restoration involves much more than planting trees.

Forest restoration aligns with other global pledges

The top 15 countries with the largest areas of restoration hotspots are distributed across all tropical rainforest regions around the world. Three are in Central and South America, five are in Africa and the Middle East, and seven are in Asia and the Pacific.

Importantly, 89% of the hotspots we identified were located within areas that have already been identified as biodiversity conservation hotspots in tropical regions. These conservation hotspots have exceptionally high concentrations of at-risk species. They have been been focal areas for investment and activities to promote biodiversity conservation for nearly 20 years.

This finding makes sense, since two criteria for designating conservation hotspots – high rates of forest loss and high concentration of endemic, or locally distributed, species – were also variables in our study. Our results strongly support the need to develop and implement integrated solutions that protect remaining forest ecosystems and restore new forests within these high-priority regions.

We also found that 73% of tropical forest restoration hotspots are in countries that have made commitments under the Bonn Challenge, a global effort to bring some 580,000 square miles (150 million hectares) of the world’s deforested and damaged land into restoration by 2020, and 1.35 million square miles (350 million hectares) by 2030. By making these pledges, Bonn Challenge participants have shown that they are politically motivated to restore and conserve forests, and are looking for restoration opportunities.

Forest restoration on small farms bordering Mpanga Forest Reserve, Uganda, can bring high levels of benefits and is relatively feasible to achieve. Robin Chazdon, CC BY-ND

A means toward many ends

The 88% of the lands we analyzed that did not qualify as restoration hotspots also deserve careful attention. These landscapes could be prioritized for restoration interventions that increase food, water and fuel security through agroforestry practices, watershed protection, woodlots for producing firewood and local timber or commercial tree plantations. All of these areas can provide benefits for people and the environment through combinations of different restoration approaches, even if they are not the best candidates for a full-scale effort to restore a high-functioning forest.

Forest restoration is also urgently needed in other types of forests across the world, such as seasonally dry tropical forests and temperate forests that are heavily managed for timber. Identifying key restoration opportunities in these regions requires separate studies based on their unique benefits and challenges.

Our study helps to highlight how restoring tropical forests can provide multiple benefits for people and nature, and aligns with existing conservation and sustainable development agendas, as discussed in a newly published perspective related to the new findings in Science. We hope that our map of restoration opportunities and hotspots will provide useful guidance for nations, conservation organizations and funders, and that local communities and organizations will be engaged in and benefit from these efforts.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65934

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Illegal Logging and Deforestation in Africa.

Amazon fires bring attention to Africa’s forests in flame

In central Africa, forests are ablaze due to agricultural techniques.

by Samir Tounsi for Agence France-Presse

In NASA satellite images, forest fires in central Africa appear to burn alarmingly like a red chain from Gabon to Angola similar to the blazes in Brazil’s Amazon that sparked global outcry.

At the G7 summit this week, French President Emmanuel Macron tweeted about the central Africa fires and said nations were examining a similar initiative to the one proposed to combat Brazil’s blazes.

G7 nations have pledged $20 million on the Amazon, mainly on fire-fighting aircraft.

Africa’s rainforest fires classed as ‘seasonal’

by AFP 2019-08-27 09:46in News

Macron’s concern may be legitimate, but experts say central Africa’s rainforest fires are often more seasonal and linked to traditional seasonal farming methods.

No doubt the region is key for the climate: The Congo Basin forest is commonly referred to as the “second green lung” of the planet after the Amazon.

The forests cover an area of 3.3 million square kilometres in several countries, including about a third in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the rest in Gabon, Congo, Cameroon and Central Africa.

Just like the Amazon, the forests of the Congo Basin absorb tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) in trees and peat marshes – seen by experts as a key way to combat climate change. They are also sanctuaries for endangered species.

But most of the fires shown on the NASA maps of Africa are outside sensitive rainforest areas, analysts say, and drawing comparisons to the Amazon is also complex.

“The question now is to what extent we can compare,”

“Fire is quite a regular thing in Africa. It’s part of a cycle, people in the dry season set fire to bush rather than to dense, moist rainforest.”

Philippe Verbelen, a Greenpeace forest campaigner working on the Congo Basin.

Guillaume Lescuyer, a central African expert at the French agricultural research and development centre CIRAD, also said the fires seen in NASA images were mostly burning outside the rain forest.

Angola’s government also urged caution, saying swift comparisons to the Amazon may lead to “misinformation of more reckless minds”.

The fires were usual at the end of the dry season, the Angolan ministry of environment said.

“It happens at this time of the year, in many parts of our country, and fires are caused by farmers with the land in its preparation phase, because of the proximity of the rainy season,” it said.

‘Different risks’ to the Amazon fires

Though less publicised than the Amazon, the Congo Basin forests still face dangers.

“In the Amazon, the forest burns mainly because of drought and climate change, but in central Africa, it is mainly due to agricultural techniques.”

Many farmers use slash-and-burn farming to clear forest. In DR Congo, only nine percent of the population has access to electricity and many people use wood for cooking and energy.

DR Congo President Felix Tshisekedi has warned the rainforests are threatened if the country does not improve its hydro-electric capacity.

Deforestation is also a risk in Gabon and parts of the DR Congo, as well as damage from mining and oil projects.

Some countries are now implementing stricter environmental policies. Gabon, for example, has declared 13 national parks that make up 11 percent of its national territory.

DR Congo has declared a moratorium on new industrial logging licences but that has not stopped artisanal cutting, which industrial loggers can

exploit.

“The forest burns in Africa but not for the same causes,” said Tosi Mpanu Mpanu, an ambassador and climate negotiator for the DR Congo.

“We need to protect the forests that are still largely intact and stop degradation,” said Greenpeace’s Verbelen. “The forests that are still intact remain an important buffer for future climate change.”

In central Africa, forests are ablaze due to agricultural techniques.

by Samir Tounsi for Agence France-Presse

In NASA satellite images, forest fires in central Africa appear to burn alarmingly like a red chain from Gabon to Angola similar to the blazes in Brazil’s Amazon that sparked global outcry.

At the G7 summit this week, French President Emmanuel Macron tweeted about the central Africa fires and said nations were examining a similar initiative to the one proposed to combat Brazil’s blazes.

G7 nations have pledged $20 million on the Amazon, mainly on fire-fighting aircraft.

Africa’s rainforest fires classed as ‘seasonal’

by AFP 2019-08-27 09:46in News

Macron’s concern may be legitimate, but experts say central Africa’s rainforest fires are often more seasonal and linked to traditional seasonal farming methods.

No doubt the region is key for the climate: The Congo Basin forest is commonly referred to as the “second green lung” of the planet after the Amazon.

The forests cover an area of 3.3 million square kilometres in several countries, including about a third in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the rest in Gabon, Congo, Cameroon and Central Africa.

Just like the Amazon, the forests of the Congo Basin absorb tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) in trees and peat marshes – seen by experts as a key way to combat climate change. They are also sanctuaries for endangered species.

But most of the fires shown on the NASA maps of Africa are outside sensitive rainforest areas, analysts say, and drawing comparisons to the Amazon is also complex.

“The question now is to what extent we can compare,”

“Fire is quite a regular thing in Africa. It’s part of a cycle, people in the dry season set fire to bush rather than to dense, moist rainforest.”

Philippe Verbelen, a Greenpeace forest campaigner working on the Congo Basin.

Guillaume Lescuyer, a central African expert at the French agricultural research and development centre CIRAD, also said the fires seen in NASA images were mostly burning outside the rain forest.

Angola’s government also urged caution, saying swift comparisons to the Amazon may lead to “misinformation of more reckless minds”.

The fires were usual at the end of the dry season, the Angolan ministry of environment said.

“It happens at this time of the year, in many parts of our country, and fires are caused by farmers with the land in its preparation phase, because of the proximity of the rainy season,” it said.

‘Different risks’ to the Amazon fires

Though less publicised than the Amazon, the Congo Basin forests still face dangers.

“In the Amazon, the forest burns mainly because of drought and climate change, but in central Africa, it is mainly due to agricultural techniques.”

Many farmers use slash-and-burn farming to clear forest. In DR Congo, only nine percent of the population has access to electricity and many people use wood for cooking and energy.

DR Congo President Felix Tshisekedi has warned the rainforests are threatened if the country does not improve its hydro-electric capacity.

Deforestation is also a risk in Gabon and parts of the DR Congo, as well as damage from mining and oil projects.

Some countries are now implementing stricter environmental policies. Gabon, for example, has declared 13 national parks that make up 11 percent of its national territory.

DR Congo has declared a moratorium on new industrial logging licences but that has not stopped artisanal cutting, which industrial loggers can

exploit.

“The forest burns in Africa but not for the same causes,” said Tosi Mpanu Mpanu, an ambassador and climate negotiator for the DR Congo.

“We need to protect the forests that are still largely intact and stop degradation,” said Greenpeace’s Verbelen. “The forests that are still intact remain an important buffer for future climate change.”

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65934

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Illegal Logging and Deforestation in Africa.

‘We have cut them all’: Ghana struggles to protect its last old-growth forests

BY AWUDU SALAMI SULEMANA YODA ON 28 AUGUST 2019

Mongabay Series: Forest Trackers

- Deforestation of Ghana’s primary forests jumped 60 percent between 2017 and 2018 – the biggest jump of any tropical country. Most of this occurred in the country’s protected areas, including its forest reserves.

- A Mongabay investigation revealed that illegal logging in forest reserves is commonplace, with sources claiming officers from Ghana’s Forestry Commission often turn a blind eye and even participate in the activity.

- The technical director of forestry at Ghana’s Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources said attempts at intervention have met with limited success, and are often thwarted by loggers who know how to game the system.

- A representative of a conservation NGO operating in the country says a community-based monitoring project has helped curtail illegal logging in some reserves, but additional buy-in from other communities is needed to scale up its results. Meanwhile, the Ghanaian government is reportedly starting its own public outreach program, as well as coordinating with the EU on an agreement that would allow only legal wood from Ghana to enter the EU market.

KUMASI, Ghana — The West African country of Ghana is known for having rich natural resources including vast tracts of rainforest. But its primary forest has all but vanished, with what remains generally relegated to reserves scattered throughout the country’s southern third.

These reserves are under official protection. However, that hasn’t stopped logging and other illegal activities from deforesting them.

An analysis of satellite data published earlier this year by U.S.-based World Resource Institute (WRI), found Ghana experienced the biggest relative increase in primary forest loss of all tropical countries last year. According to the report, the loss of Ghana’s primary forest cover jumped 60 percent from 2017 to 2018 – almost entirely from its protected areas.

Most of Ghana’s primary forests are gone and, like puzzle pieces of dark green scattered across the landscape, the fragmented remainder are

shielded in protected areas. However, those protections appear to be failing, with satellite data indicating 2019 may be continuing 2018’s record-breaking deforestation trend. Source: GLAD/UMD, accessed through Global Forest Watch.

WRI found that while mining and logging were partly to blame for Ghana’s deforestation, the expansion of cocoa farms was the main culprit.

In response to WRI’s report, the Ghanaian government issued a statement through its Forestry Commission denying the findings. In its statement, the Forestry Commission said the WRI report was based on a faulty methodology as well as a misunderstanding of current controlled agricultural practices in Ghana. It refuted the 60 percent figure, saying instead that Ghana’s primary forest loss had increased by 31 percent between 2017 and 2018.

A publication by data analytics company Satelligence, however, affirmed WRI’s findings that Ghana deforestation did indeed experience a 60 percent jump. However, Satelligence’s report differs in one significant aspect from WRI’s: it says cocoa is not the main driver of deforestation in Ghana, instead laying blame on logging, mining, fire, and industrial agricultural expansion for other kinds of crops.

Forest reserves under attack

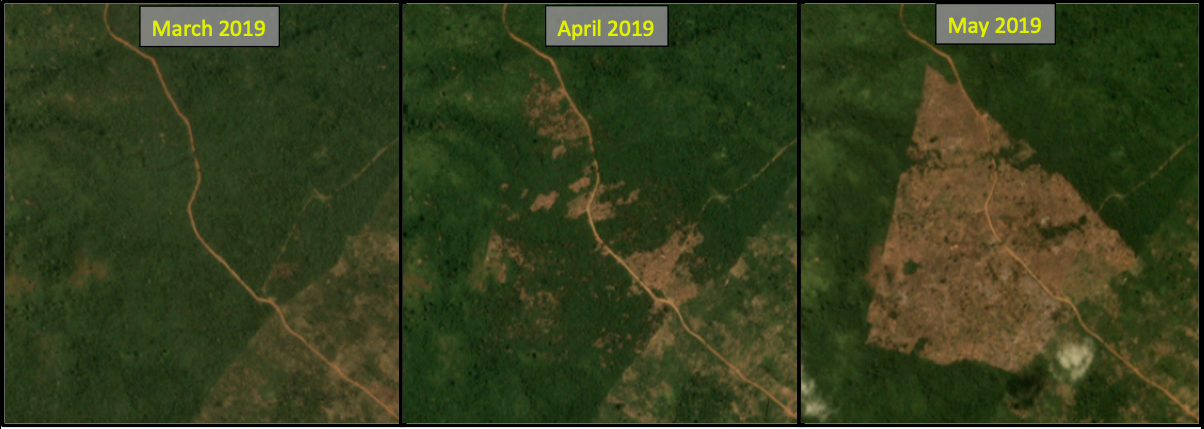

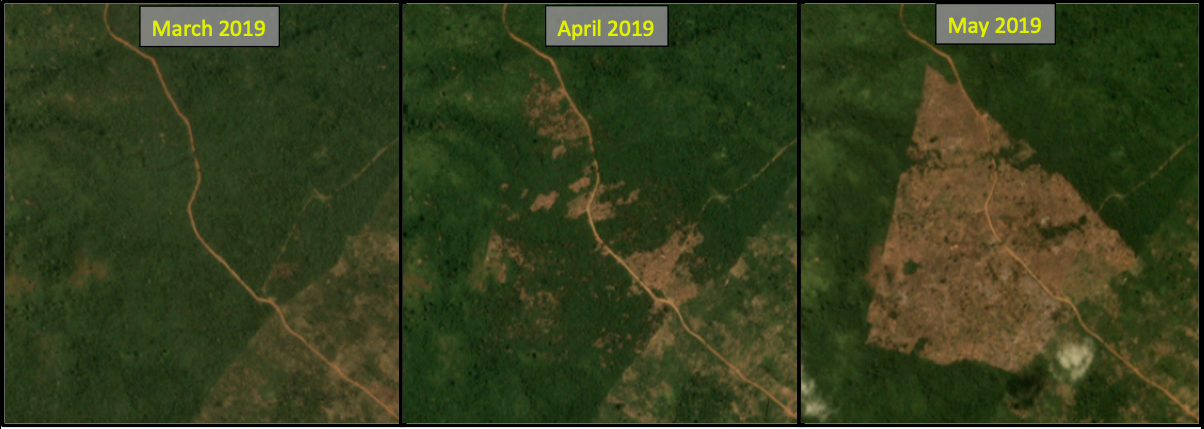

Ghana’s last remaining tracts of primary forest can only be found within areas granted official protection. However, even these are no longer immune to the advance of deforestation, with many hit hard by a surge of forest loss that began in April.

Stretching more than 20 kilometers (12 miles) along a bank of hills in the Ashanti region of southern Ghana, Tano-Offin Forest Reserve has lost more than 16 percent of its old-growth forest since 2001, according to satellite data from the University of Maryland. Several areas of the reserve are completely devoid of large trees, while the roar of chainsaws is ever-present, operated with impunity.

A clearcut area 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) wide was carved from Tano-Offin earlier this year. Imagery from Planet Labs, accessed via Global Forest Watch.

Sources on the ground say that illegal logging done at the hands of Ghanaian nationals as well as foreigners, especially Chinese nationals, appears to be the main cause of deforestation in the reserve.

“If you have come to look for trees in this forest then forget it because we have cut them all,” said a chainsaw operator who was illegally felling trees in the reserve to sell to a local buyer. The buyer showed up with a truck to haul off the logs.

Anane Frempong, the political head, or “assemblyman,” in Ghanaian parlance, of the Kyekyewere electoral area that comprises Tano-Offin, told Mongabay that his outfit seized some 6,000 pieces of timber last year that were harvested illegally in the reserve. These were handed over to officials from the Forestry Commission, which has established a task force to prevent illegal logging.

A truck transports recently felled timber near Tano-Offin Forest Reserve. Image by Awudu Salami Sulemana Yoda for Mongabay.

However, efforts to protect forests are often stymied. The chainsaw operator told Mongabay that loggers routinely bribed members of the task force to look the other way. This has seemingly created a situation of impunity, with trucks carrying timber in broad daylight from the reserve to the city of Kumasi a common sight, even though the Forestry Commission has set up checkpoints along the route. See Pictures

Fire, farms and mines

Illegal timber harvesting isn’t the only activity driving deforestation in Tano-Offin. Bush fires, set to clear land and aided by the dry harmattan season from November to March, have consumed large swaths of forest.

Human settlement in Tano-Offin has also contributed to the destruction of its forest. Half a dozen communities are situated deep inside the reserve, of which Kyekyewere is the largest. With a population of more than 1,000, Kyekyewere has some trappings of a modern town, including a school that provides education from the kindergarten level to junior high. However, there is no medical facility or electricity, and most community members depend on farming to survive.

The town of Kyekyewere lies within Tano-Offin. Image by Awudu Salami Sulemana Yoda for Mongabay.

Frempong, the Kyekyewere assemblyman, told Mongabay that the community had existed in the forest for more than 200 years, and that its residents had no other place to go. He said forest guards intimidated and harassed them whenever they farmed in the forest, alleging that last year they forced a resident of the community to swallow a dry plantain leaf, which Frempong says led to the man’s death a few days later.

“To mitigate this conflict, I will humbly appeal to the government of Ghana through the Forestry Commission to demarcate an area for farmland in the reserve to enable members of the community to have food to eat, as we have nowhere to call our town apart from the Kyekyewere community,” Frempong said.

Part of Tano-Offin is also rich in bauxite, which has prompted the Ghana Integrated Aluminium Corporation to begin establishing mining operations in the reserve. While mining has not yet started, infrastructure development is underway, with roads to prospective mining sites currently under construction.

Residents have expressed concern about the impacts mining might have on the forest, among them Nana Oppong Dinkyine. He told Mongabay that deforestation is already affecting water resources.

“The continuous depletion of the forest is seriously having a negative effect on our livelihood as our water bodies are being dried up and with the amount of rainfall dropping every year in this community, we are likely to face acute water shortage in the near future,” Dinkyine said. “That is why we are going to resist the mining operation in the forest — to protect our rivers.”

Bia Tano Forest Reserve is located about 30 kilometers (19 miles) northwest of Tano-Offin. Here, illegal logging is also underway. But sources say that Forestry Commission officials aren’t just allowing logging here — they’re actively participating in it.

African bush elephants (Loxodonta africana) can still be found in Bia Tano Forest Reserve. They’re listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN. Photo by Rhett Butler/Mongabay.

Mongabay observed loggers transporting timber from Bia Tano through a checkpoint immediately west of the reserve. When confronted by the forest guard manning the checkpoint, one of the loggers said a forestry officer from Goaso district had allowed them to cut down trees in the reserve.

Upon hearing that the loggers had official permission, the guard allowed them to proceed.

“This is the challenge confronting us here,” said the guard, who asked not to be named. “Public officials are deeply involved in the illegal activities.”

Mongabay reached out to Ghana’s Forestry Commission, but requests for comment were not answered by the time this story was published.

Another forest guard who also spoke to Mongabay on condition of anonymity said that state officials were also giving out concessions in the reserve to their crops.

Trees cut down in Bia Tano Forest Reserve lie on the recently denuded ground. Image by Awudu Salami Sulemana Yoda for Mongabay.

Timber is often transported from Bia Tano via modified motorbikes. Image by Awudu Salami Sulemana Yoda for Mongabay.

At the Bediakokrom community just east of Bia Tano, dozens of sawmills can be seen just outside the reserve. The second forest guard told Mongabay that most of the owners of the sawmills had no permit to work in the reserve, but continued to log its forests.

Community leader Agya Bomba blamed the now-defunct Ayum Timber Company for the increase in illegal logging in Bia Tano. He said that a concession once leased by the company had since been invaded by illegal loggers, including former company staff.

Fighting back

Illegal logging in Ghana’s forest reserves was confirmed by Musah Abu-Juam, technical director in charge of forestry at Ghana’s Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources, who said the practice was ongoing both inside and outside protected areas.

“Because of the low number of the officials of the Forestry Commission, we still have high incidence of chainsawing both outside and inside the forest reserves,” he said.

Abu-Juam said the government was doing its best to fight back against illegal deforestation. He referred to one incident in which the Forestry Commission stopped buses loaded with illegal timber from a forest reserve and arrested the perpetrators.

However, Abu-Juam said that although the government of Ghana was making an effort to improve the monitoring mechanisms in the reserves, those involved in the illegal activity often find ways to outwit these measures. He cited a case in which illegal operators tried fooling forest guards by entering a reserve during the night, cutting down trees, and making them into semi-finished doors in the forest before transporting them out before daybreak.

Milled planks being transported outside of Bia Tano Forest Reserve. Image by Awudu Salami Sulemana Yoda for Mongabay.

He also mentioned a recent arrest made when Forestry Commission officials discovered loggers were transporting illegal wood from a reserve by hiding it in coffins.

Abu-Juam said the government had introduced a program rewarding people who report illegal logging. However, he said the program suffered a setback as illegal operators impersonated whistle-blowers to send forestry officials on a wild goose chase in one area while they logged in another.

He also blamed deforestation on forest-dependent communities, saying “their continuous expansion is destructive to the reserves in which they live.”

However, some say these communities could also be a key to saving Ghana’s forest reserves. Friends of the Earth (FoE) Ghana, an NGO, has initiated a program called “community-based real-time monitoring” to try and clamp down on the country’s rampant illegal logging.

Dennis Acquah, project coordinator for FoE-Ghana, said the program has helped build capacity in communities living within forests to detect and report illegal activities as they’re happening by using a mobile phone app.

“With the project, FoE-Ghana selected some members of the forest fringe communities, trained them to be conversant with forest laws and mobile systems applications … to collect and transmit quality data, which can be in a form of video, audio or picture, and transmit the data onto [a] centralized database,” Acquah said. “FoE then collaborate[s] with the Forestry Commission for verification of the alerts and then take action.”

Acquah said the project had yielded positive results, including driving many illegal loggers from reserves and the confiscation of illegal timber. He said this success could be scaled up and urged the involvement of all forest communities.

The race is on to protect Ghana’s remaining old-growth forests. Image by Awudu Salami Sulemana Yoda for Mongabay.

According to Abu-Juam, the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources is also engaging members of the public, particularly those living around the reserves, to fight illegal logging. He added that a special court had been established, with trained local forestry officials acting as prosecutors to deal with cases involving illegal operators in the reserves.

Ghana is also tapping into international support to combat illegal logging. Abu-Juam said the governments of Ghana and the European Union had entered into an agreement that would allow only legal wood to enter the EU market, and had established the Legality Assurance System, which tracks each piece of timber from where it is cut to where it is sold.

“The government of Ghana has reached very far with the EU to make the agreement work and it will soon issue the forest law enforcement, governance and trade license for the agreement to take [effect],” Abu-Juam told Mongabay.

Editor’s note: This story was powered by Places to Watch, a Global Forest Watch (GFW) initiative designed to quickly identify concerning forest loss around the world and catalyze further investigation of these areas. Places to Watch draws on a combination of near-real-time satellite data, automated algorithms and field intelligence to identify new areas on a monthly basis. In partnership with Mongabay, GFW is supporting data-driven journalism by providing data and maps generated by Places to Watch. Mongabay maintains complete editorial independence over the stories reported using this data.

BY AWUDU SALAMI SULEMANA YODA ON 28 AUGUST 2019

Mongabay Series: Forest Trackers

- Deforestation of Ghana’s primary forests jumped 60 percent between 2017 and 2018 – the biggest jump of any tropical country. Most of this occurred in the country’s protected areas, including its forest reserves.

- A Mongabay investigation revealed that illegal logging in forest reserves is commonplace, with sources claiming officers from Ghana’s Forestry Commission often turn a blind eye and even participate in the activity.

- The technical director of forestry at Ghana’s Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources said attempts at intervention have met with limited success, and are often thwarted by loggers who know how to game the system.

- A representative of a conservation NGO operating in the country says a community-based monitoring project has helped curtail illegal logging in some reserves, but additional buy-in from other communities is needed to scale up its results. Meanwhile, the Ghanaian government is reportedly starting its own public outreach program, as well as coordinating with the EU on an agreement that would allow only legal wood from Ghana to enter the EU market.

KUMASI, Ghana — The West African country of Ghana is known for having rich natural resources including vast tracts of rainforest. But its primary forest has all but vanished, with what remains generally relegated to reserves scattered throughout the country’s southern third.

These reserves are under official protection. However, that hasn’t stopped logging and other illegal activities from deforesting them.

An analysis of satellite data published earlier this year by U.S.-based World Resource Institute (WRI), found Ghana experienced the biggest relative increase in primary forest loss of all tropical countries last year. According to the report, the loss of Ghana’s primary forest cover jumped 60 percent from 2017 to 2018 – almost entirely from its protected areas.

Most of Ghana’s primary forests are gone and, like puzzle pieces of dark green scattered across the landscape, the fragmented remainder are

shielded in protected areas. However, those protections appear to be failing, with satellite data indicating 2019 may be continuing 2018’s record-breaking deforestation trend. Source: GLAD/UMD, accessed through Global Forest Watch.

WRI found that while mining and logging were partly to blame for Ghana’s deforestation, the expansion of cocoa farms was the main culprit.

In response to WRI’s report, the Ghanaian government issued a statement through its Forestry Commission denying the findings. In its statement, the Forestry Commission said the WRI report was based on a faulty methodology as well as a misunderstanding of current controlled agricultural practices in Ghana. It refuted the 60 percent figure, saying instead that Ghana’s primary forest loss had increased by 31 percent between 2017 and 2018.

A publication by data analytics company Satelligence, however, affirmed WRI’s findings that Ghana deforestation did indeed experience a 60 percent jump. However, Satelligence’s report differs in one significant aspect from WRI’s: it says cocoa is not the main driver of deforestation in Ghana, instead laying blame on logging, mining, fire, and industrial agricultural expansion for other kinds of crops.

Forest reserves under attack

Ghana’s last remaining tracts of primary forest can only be found within areas granted official protection. However, even these are no longer immune to the advance of deforestation, with many hit hard by a surge of forest loss that began in April.

Stretching more than 20 kilometers (12 miles) along a bank of hills in the Ashanti region of southern Ghana, Tano-Offin Forest Reserve has lost more than 16 percent of its old-growth forest since 2001, according to satellite data from the University of Maryland. Several areas of the reserve are completely devoid of large trees, while the roar of chainsaws is ever-present, operated with impunity.

A clearcut area 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) wide was carved from Tano-Offin earlier this year. Imagery from Planet Labs, accessed via Global Forest Watch.

Sources on the ground say that illegal logging done at the hands of Ghanaian nationals as well as foreigners, especially Chinese nationals, appears to be the main cause of deforestation in the reserve.

“If you have come to look for trees in this forest then forget it because we have cut them all,” said a chainsaw operator who was illegally felling trees in the reserve to sell to a local buyer. The buyer showed up with a truck to haul off the logs.

Anane Frempong, the political head, or “assemblyman,” in Ghanaian parlance, of the Kyekyewere electoral area that comprises Tano-Offin, told Mongabay that his outfit seized some 6,000 pieces of timber last year that were harvested illegally in the reserve. These were handed over to officials from the Forestry Commission, which has established a task force to prevent illegal logging.

A truck transports recently felled timber near Tano-Offin Forest Reserve. Image by Awudu Salami Sulemana Yoda for Mongabay.

However, efforts to protect forests are often stymied. The chainsaw operator told Mongabay that loggers routinely bribed members of the task force to look the other way. This has seemingly created a situation of impunity, with trucks carrying timber in broad daylight from the reserve to the city of Kumasi a common sight, even though the Forestry Commission has set up checkpoints along the route. See Pictures

Fire, farms and mines

Illegal timber harvesting isn’t the only activity driving deforestation in Tano-Offin. Bush fires, set to clear land and aided by the dry harmattan season from November to March, have consumed large swaths of forest.

Human settlement in Tano-Offin has also contributed to the destruction of its forest. Half a dozen communities are situated deep inside the reserve, of which Kyekyewere is the largest. With a population of more than 1,000, Kyekyewere has some trappings of a modern town, including a school that provides education from the kindergarten level to junior high. However, there is no medical facility or electricity, and most community members depend on farming to survive.

The town of Kyekyewere lies within Tano-Offin. Image by Awudu Salami Sulemana Yoda for Mongabay.

Frempong, the Kyekyewere assemblyman, told Mongabay that the community had existed in the forest for more than 200 years, and that its residents had no other place to go. He said forest guards intimidated and harassed them whenever they farmed in the forest, alleging that last year they forced a resident of the community to swallow a dry plantain leaf, which Frempong says led to the man’s death a few days later.

“To mitigate this conflict, I will humbly appeal to the government of Ghana through the Forestry Commission to demarcate an area for farmland in the reserve to enable members of the community to have food to eat, as we have nowhere to call our town apart from the Kyekyewere community,” Frempong said.

Part of Tano-Offin is also rich in bauxite, which has prompted the Ghana Integrated Aluminium Corporation to begin establishing mining operations in the reserve. While mining has not yet started, infrastructure development is underway, with roads to prospective mining sites currently under construction.

Residents have expressed concern about the impacts mining might have on the forest, among them Nana Oppong Dinkyine. He told Mongabay that deforestation is already affecting water resources.

“The continuous depletion of the forest is seriously having a negative effect on our livelihood as our water bodies are being dried up and with the amount of rainfall dropping every year in this community, we are likely to face acute water shortage in the near future,” Dinkyine said. “That is why we are going to resist the mining operation in the forest — to protect our rivers.”

Bia Tano Forest Reserve is located about 30 kilometers (19 miles) northwest of Tano-Offin. Here, illegal logging is also underway. But sources say that Forestry Commission officials aren’t just allowing logging here — they’re actively participating in it.

African bush elephants (Loxodonta africana) can still be found in Bia Tano Forest Reserve. They’re listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN. Photo by Rhett Butler/Mongabay.

Mongabay observed loggers transporting timber from Bia Tano through a checkpoint immediately west of the reserve. When confronted by the forest guard manning the checkpoint, one of the loggers said a forestry officer from Goaso district had allowed them to cut down trees in the reserve.

Upon hearing that the loggers had official permission, the guard allowed them to proceed.

“This is the challenge confronting us here,” said the guard, who asked not to be named. “Public officials are deeply involved in the illegal activities.”

Mongabay reached out to Ghana’s Forestry Commission, but requests for comment were not answered by the time this story was published.

Another forest guard who also spoke to Mongabay on condition of anonymity said that state officials were also giving out concessions in the reserve to their crops.

Trees cut down in Bia Tano Forest Reserve lie on the recently denuded ground. Image by Awudu Salami Sulemana Yoda for Mongabay.

Timber is often transported from Bia Tano via modified motorbikes. Image by Awudu Salami Sulemana Yoda for Mongabay.

At the Bediakokrom community just east of Bia Tano, dozens of sawmills can be seen just outside the reserve. The second forest guard told Mongabay that most of the owners of the sawmills had no permit to work in the reserve, but continued to log its forests.

Community leader Agya Bomba blamed the now-defunct Ayum Timber Company for the increase in illegal logging in Bia Tano. He said that a concession once leased by the company had since been invaded by illegal loggers, including former company staff.

Fighting back

Illegal logging in Ghana’s forest reserves was confirmed by Musah Abu-Juam, technical director in charge of forestry at Ghana’s Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources, who said the practice was ongoing both inside and outside protected areas.

“Because of the low number of the officials of the Forestry Commission, we still have high incidence of chainsawing both outside and inside the forest reserves,” he said.

Abu-Juam said the government was doing its best to fight back against illegal deforestation. He referred to one incident in which the Forestry Commission stopped buses loaded with illegal timber from a forest reserve and arrested the perpetrators.

However, Abu-Juam said that although the government of Ghana was making an effort to improve the monitoring mechanisms in the reserves, those involved in the illegal activity often find ways to outwit these measures. He cited a case in which illegal operators tried fooling forest guards by entering a reserve during the night, cutting down trees, and making them into semi-finished doors in the forest before transporting them out before daybreak.

Milled planks being transported outside of Bia Tano Forest Reserve. Image by Awudu Salami Sulemana Yoda for Mongabay.

He also mentioned a recent arrest made when Forestry Commission officials discovered loggers were transporting illegal wood from a reserve by hiding it in coffins.

Abu-Juam said the government had introduced a program rewarding people who report illegal logging. However, he said the program suffered a setback as illegal operators impersonated whistle-blowers to send forestry officials on a wild goose chase in one area while they logged in another.

He also blamed deforestation on forest-dependent communities, saying “their continuous expansion is destructive to the reserves in which they live.”

However, some say these communities could also be a key to saving Ghana’s forest reserves. Friends of the Earth (FoE) Ghana, an NGO, has initiated a program called “community-based real-time monitoring” to try and clamp down on the country’s rampant illegal logging.

Dennis Acquah, project coordinator for FoE-Ghana, said the program has helped build capacity in communities living within forests to detect and report illegal activities as they’re happening by using a mobile phone app.

“With the project, FoE-Ghana selected some members of the forest fringe communities, trained them to be conversant with forest laws and mobile systems applications … to collect and transmit quality data, which can be in a form of video, audio or picture, and transmit the data onto [a] centralized database,” Acquah said. “FoE then collaborate[s] with the Forestry Commission for verification of the alerts and then take action.”

Acquah said the project had yielded positive results, including driving many illegal loggers from reserves and the confiscation of illegal timber. He said this success could be scaled up and urged the involvement of all forest communities.

The race is on to protect Ghana’s remaining old-growth forests. Image by Awudu Salami Sulemana Yoda for Mongabay.

According to Abu-Juam, the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources is also engaging members of the public, particularly those living around the reserves, to fight illegal logging. He added that a special court had been established, with trained local forestry officials acting as prosecutors to deal with cases involving illegal operators in the reserves.

Ghana is also tapping into international support to combat illegal logging. Abu-Juam said the governments of Ghana and the European Union had entered into an agreement that would allow only legal wood to enter the EU market, and had established the Legality Assurance System, which tracks each piece of timber from where it is cut to where it is sold.

“The government of Ghana has reached very far with the EU to make the agreement work and it will soon issue the forest law enforcement, governance and trade license for the agreement to take [effect],” Abu-Juam told Mongabay.

Editor’s note: This story was powered by Places to Watch, a Global Forest Watch (GFW) initiative designed to quickly identify concerning forest loss around the world and catalyze further investigation of these areas. Places to Watch draws on a combination of near-real-time satellite data, automated algorithms and field intelligence to identify new areas on a monthly basis. In partnership with Mongabay, GFW is supporting data-driven journalism by providing data and maps generated by Places to Watch. Mongabay maintains complete editorial independence over the stories reported using this data.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65934

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Illegal Logging and Deforestation in Africa.

Madagascar no longer insisting on selling its seized rosewood, for now

by Malavika Vyawahare on 30 August 2019

- Madagascar has withdrawn its demand to be allowed to sell illegally harvested rosewood timber that it had previously seized.

- The move aligns Madagascar’s position more closely with that of the international community, which wants the country to crack down on the

illegal logging and timber trade before a relaxation or lifting of the ban is even considered.

- However, the government hasn’t ruled out seeking permission for a sale in the future, raising concern among observers about the message this could send to illegal traders and to other countries also seeking to offload stockpiles of trafficked contraband.

A ban on the international trade in rosewood, a prized timber, remains intact following the close this week of a global summit on the trade in wild animals and plants.

What did change at the 18th Conference of the Parties (CoP18) to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) was that Madagascar, a key source country for illegal precious wood, withdrew its demand to be allowed to sell rosewood stocks that it had previously seized in the international market.

“I reiterate once again a paradigm shift that Madagascar will not consider marketing,” Lala Ranaivomanana, secretary-general of Madagascar’s Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, said at the CITES summit in Geneva. He added that the country would hold off on any plans to try and sell the stockpile until it had resolved issues surrounding inventory management and control.

While selling the rosewood remains an option in the future, the latest decision aligns Madagascar’s position more closely with that of CITES: that the country needs to do more to crack down on the illegal logging and timber trade before a relaxation or lifting of the ban is even considered.

“The first thing they need to address is the enforcement issue. The potential conversation on exports and sustainable management will come after that,” said Isabel Camarena, an official with the CITES Secretariat who tracked the discussions.

In a July interview Alexandre Georget, Madagascar’s environment minister, told Mongabay that they would not allow any exports of rosewood. In the past, the country has repeatedly sought permission for a one-time sale of illegal rosewood that lies in government custody, a move that many fear would send the wrong signal to illegal traders and to other countries pushing for similar sales of trafficked commodities.

“WCS commends Madagascar for announcing that they are no longer seeking permission from CITES for an international sale of seized stocks of rosewood,” Janice Weatherley-Singh, a director at the Wildlife Conservation Society-EU, said in a statement. “Allowing even just a one-off international sale of such a highly prized wood would provide an opportunity for increased illegal trade.”

A 2009 coup led by the current president, Andry Rajoelina, fueled unprecedented destruction of Madagascar’s forests and rosewood extraction. The 2013 CITES ban led to a government roundup of illegally harvested rosewood. To date, however, Madagascar still doesn’t have a clear idea of how much illegal rosewood exists in the country, because some stocks have been declared by traffickers but aren’t in government custody, while others have been stashed away by timber traders.

Without this baseline, the CITES committee is unwilling to consider any move to dispose of it. Madagascar said domestic use would be prioritized rather than allowing the wood to enter the global market, ending up largely in China.

Wood from species in two genera found in Madagascar, Dalbergia (rosewood and palisander) and Diospyros (ebony), is considered precious timber. It’s coveted for its rich hues and fragrance and used in the production of fine furniture and musical instruments.

During the 2013 CITES summit, in Bangkok, rosewood, ebony and palisander from Madagascar were placed in Appendix II of the convention. That means that while trade isn’t banned, it’s subject to strict regulation. An embargo was placed on trade in the precious timber, and an action plan approved to create an inventory of stockpiles and assess standing trees.

Since then, CITES has extended the embargo and rejected iterations of the “Stockpile Verification Mechanism and Business Plan” presented by the Malagasy government for auditing and ultimately legally exporting the stock of precious wood in its custody.

The justification offered by the government was that selling the confiscated timber would help it achieve “stock zero” and make it easier to track any new logging. But without accurate and reliable information about the volume of confiscated timber, there’s no knowing how much would have to be sold off to arrive at “stock zero.” There’s the added concern that timber traffickers could freely remove and sell logs from the cache that’s not fully under government control.

The Malagasy government has been criticized for trying to take control of the inventory by compensating timber barons who control a substantial portion of the illegal stocks.

At the CITES summit in Geneva, it was decided that Madagascar would account for all the stocks, not only a third of them as was previously required , including the undeclared and hidden ones, according to Susanne Breitkopf, forest policy manager at the Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group Environmental Investigations Agency, which participated as an observer at the meeting. Madagascar also committed to enforce the law and prosecute offenders at all levels.

The shift in the government’s stance is being hailed by some, while others are more cautious in their optimism.

“They did not present a new business plan here, also nothing about compensating traffickers. Per CoP decision they should submit a new use plan (not business plan), to the next Standing Committee, which is based on transparency and independent oversight mechanism,” Breitkopf said.

However, government officials did not categorically rule out seeking permission for a future sale of the stockpile. “We continue working on the business plan taking account on these new recommendations,” Herizo Rakotovololonalimanana, the director-general of environment and forests and one of Madagascar’s delegates at CoP18, said in an email to Mongabay.

Ranaivomanana, in his speech at the CITES meeting, noted that the decision on what to do would come after the government had secured all the stocks, the risks of illegal exploitation were fully understood, and it was able to deal with offenders more effectively.

Camarena from the CITES Secretariat said the international community was still worried that once Madagascar did that, they might seek to sell the rosewood. “The use plan has not been approved, only the part about making the inventory,” she said. “The idea of the inventory management was well received but nobody wanted anything to do with sale.”

The conference did amend the status of small finished items such as musical instruments, parts and accessories, exempting them from requiring CITES permits to cross borders. Madagascar’s plan to use some of the stock domestically to produce handicrafts could potentially benefit from this.

However, it would only be part of the solution to the problem of what to do with the seized wood. “The needs for local handcrafts will be very small compared to the total size of the current stockpile, so this to me does not solve much of the situation and it does not mean that the stock is safe,” said Nanie Ratsifandrihamanana, the country director for WWF Madagascar, adding that “there has been no information shared on the status of the inventory so I suppose it is still at the same status as it was last year.”

At the discussion, parties felt no progress could be made by pushing Madagascar into a corner and the need was to support them, Camarena said, a theme emphasized in the decisions taken during the meeting.

“The challenge is still huge and Madagascar cannot solve the rosewood trafficking crisis in isolation,” Weatherley-Singh of WCS said. “The international trade suspension needs to be kept in place. Other countries also need to be ready to refuse imports of illegal stocks and provide financial support.”

by Malavika Vyawahare on 30 August 2019

- Madagascar has withdrawn its demand to be allowed to sell illegally harvested rosewood timber that it had previously seized.

- The move aligns Madagascar’s position more closely with that of the international community, which wants the country to crack down on the

illegal logging and timber trade before a relaxation or lifting of the ban is even considered.

- However, the government hasn’t ruled out seeking permission for a sale in the future, raising concern among observers about the message this could send to illegal traders and to other countries also seeking to offload stockpiles of trafficked contraband.

A ban on the international trade in rosewood, a prized timber, remains intact following the close this week of a global summit on the trade in wild animals and plants.

What did change at the 18th Conference of the Parties (CoP18) to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) was that Madagascar, a key source country for illegal precious wood, withdrew its demand to be allowed to sell rosewood stocks that it had previously seized in the international market.

“I reiterate once again a paradigm shift that Madagascar will not consider marketing,” Lala Ranaivomanana, secretary-general of Madagascar’s Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, said at the CITES summit in Geneva. He added that the country would hold off on any plans to try and sell the stockpile until it had resolved issues surrounding inventory management and control.

While selling the rosewood remains an option in the future, the latest decision aligns Madagascar’s position more closely with that of CITES: that the country needs to do more to crack down on the illegal logging and timber trade before a relaxation or lifting of the ban is even considered.

“The first thing they need to address is the enforcement issue. The potential conversation on exports and sustainable management will come after that,” said Isabel Camarena, an official with the CITES Secretariat who tracked the discussions.

In a July interview Alexandre Georget, Madagascar’s environment minister, told Mongabay that they would not allow any exports of rosewood. In the past, the country has repeatedly sought permission for a one-time sale of illegal rosewood that lies in government custody, a move that many fear would send the wrong signal to illegal traders and to other countries pushing for similar sales of trafficked commodities.

“WCS commends Madagascar for announcing that they are no longer seeking permission from CITES for an international sale of seized stocks of rosewood,” Janice Weatherley-Singh, a director at the Wildlife Conservation Society-EU, said in a statement. “Allowing even just a one-off international sale of such a highly prized wood would provide an opportunity for increased illegal trade.”