Rhino Horn Trade

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75552

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Horn Trade

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5858

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Horn Trade

https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/29 ... nX94pujCZg

Draft regulatory measures for trade in rhinoceros horn

Ms Magdel Boshoff, DEFF Deputy Director of Threatened or Protected Species Policy Development, presented the draft regulatory measures for trade in rhino horn – developed in terms of the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act (NEMBA) – for Committee to note them before implementation.

Background

The domestic trade in rhino horn was prohibited in February 2009 in line with CITES but the High Court in 2015 set aside the national moratorium on the domestic trade in rhino horn or any derivative thereof.

The challenges that arose were: Misuse of the permit system and laundering of illegally obtained rhino horn to export it legally for illegal international trade; Breaching of Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES); Inability to trace the origin of rhino horn of illegal origin; Demand for rhino horn for luxury goods and in Asia for medicine. The main medicinal distribution channel is powder or chunks, which made it difficult to monitor and to detect illegal trade as it was easy to conceal. The intervention was to strengthen existing legislation and improve the traceability of rhino horn.

Existing legislation involved:

- Threatened or Protected Species (TOPS) Regulations, which apply to all listed species;

- Rhino Marking & Trophy Hunting Norms and Standards 2009, amended in 2012 and 2018;

- CITES Regulations (regulating import, export and re-export of specimens of species)

To date, the following legislative have been addressed/strengthened:

- marking requirements;

- compulsory DNA collection and analysis;

- implementation of national database for the recording of markings, linked with a national auditing process;

- Minister to be issuing authority for all permits for selling / donating / buying / receiving of rhino horn.

The legislative gap yet to be addressed relates to specific areas / circumstances of trade.

Introduction

A permit is required in terms of NEMBA for the carrying out of any restricted activity involving rhino horn, regardless the size or form of such rhino horn. “Restricted activity” is defined in NEMBA, and includes activities such as possession, buying/ selling, hunting, killing, breeding, transporting, cutting off, etc.

The Rhino Norms and Standards require the compulsory marking of a rhino horn or a piece of rhino horn that is 5cm or longer in length, by means of a 10-digit microchip and a ZA serial number.

The draft regulatory measures on rhino horn trade include:

• Draft regulations aimed at regulating the lawful selling/ buying of rhino horn;

• Draft prohibitions, aimed at prohibiting certain activities involving rhino horn; and

• Draft listing notice, proposing the deletion of Eastern black rhinoceros from the list of invasive species, and the inclusion thereof in the list of threatened or protected species.

Calls for public comment were made in 2017 and 2018.

International trade in rhino horn for primarily commercial purposes remains prohibited by CITES.

Legislative Framework on Biodiversity

The Constitution is the highest authority which sets out environmental rights. The Constitution makes provision for the ratification of international agreements, like CITES. The legislative framework was also informed by the White Paper on Environmental Management. NEMBA was one of the specific environmental acts under NEMA. In terms of the Constitution, provinces or MECs have an equal mandate to make and implement nature conservation legislation. According to NEMBA, the Minister has the authority to make regulations, norms and standards, prohibit an activity that may negatively impact on the survival of a species and implement and publish a Biodiversity Management Plan.

Prohibitions

A person may not powder a rhino horn, or create slivers, drill bits, chips or similar derivatives, excluding under the following circumstances:

- during the insertion of a microchip or tracking device

- during the de-horning of a rhino

- when collecting a DNA sample of the horn

A person may not sell / donate / give / buy / receive or accept as donation / export / re-export, powdered rhino horn, or rhino horn smaller than 5 cm in length.

The prohibitions remain in place for a period of three years after the commencement of the notice, after which the Minister will assess and re-consider the prohibitions.

Regulations

Rhino horn may be sold only if it is 5cm or more in length. Requirements to obtain a selling permit:

- certified copy of the ID or similar document

- certified copy of the possession permit

- the rhino horn must be appropriately marked

- certified copy of the genetic profiling report

- photograph of suitable quality of each horn

- measurements (length along inner and outer curve, base circumference) and weight of each horn

- inspection by the relevant issuing authority

- recording of the information on the national database.

Prohibitions (imposed through the regulations):

- selling of rhino horn originating from other countries

- export of rhino horn through ports of exist other than OR Tambo International Airport

Requirements for online auctions:

- seller must have a selling permit at the time of bidding as the auction

- selling and buying permits must be valid for the date, or period, of the auction

- person who intends to bid at auction, must apply for buying permit at least 30 working days prior to auction.

- holder of buying permit must return permit within 5 working days of auction, if bid was not successful

- seller must provide DEFF with a list of registered bidders 48 hours prior to auction

- seller must provide DEFF with a list of successful bidders, within 5 working days of auction.

Other provisions:

- holder of selling permit may give proxy (in writing) to another person (excluding a foreign person) to sell the rhino horn (the same applies to buying)

- where a proxy applies, the seller/buyer, and the proxy holder, must be in possession of a permit

- holder of buying/selling permit must be present in the country at the time of buying/selling of a rhino horn

- seller remains responsible for safe-keeping until the possession permit of the buyer has been issued

- buyer may not take possession of the rhino horn until possession permit has been issued

- certified copy of a document remains valid for six months after the validation of the document.

Listing notice

The Eastern black rhino is removed from the list of invasive species and is included in the list of protected species in terms of NEMBA. The implications are that all these regulations and prohibitions apply to Eastern black rhino. When the listing notice commences, the TOPS Regulations and the Rhino Norms and Standards will also apply to Eastern black rhino.

Ms Boshoff asked the Select Committee to take note of the draft regulatory measures for domestic trade in rhino horn, developed in terms of NEMBA.

Discussion

Ms Labuschagne asked about the Animal Improvement Act passed in May that re-categorised wild life as farming stock. This included rhinos. Will these regulations still apply to someone who decides to farm rhinos?

Mr Cloete asked about the effect of these draft regulatory measures – was DEFF confident that provinces will still be able to make regulations specific to their provinces and that important authority would not be taken away from the provinces?

Ms Boshoff responded about the farming of animals according to the Animal Improvement Act. NEMBA and its regulations will apply alongside the Animal Improvement Act and its regulations. Provinces will still be able to make regulations according to their provincial ordinances. However, provinces have to be mindful of the constitutional requirement that all legislation needs to be aligned. When provinces do make regulations they need to ensure they are not in conflict with national legislation. NEMBA is not intended to take away the authority of provincial legislation.

Minister Creecy said that she understands that the Committee would like a little bit longer to consider the proposed regulations. She appealed to the Committee to understand that a policy vacuum exists and that these regulations were needed as soon as possible to combat the illegal trade of rhino horn.

The Chairperson thanked the Minister and her team. The minutes of the previous meeting was adopted and the meeting adjourned.

Presentation: https://pmg.org.za/files/191112Regulatory_measures.pptx

Draft regulatory measures for trade in rhinoceros horn

Ms Magdel Boshoff, DEFF Deputy Director of Threatened or Protected Species Policy Development, presented the draft regulatory measures for trade in rhino horn – developed in terms of the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act (NEMBA) – for Committee to note them before implementation.

Background

The domestic trade in rhino horn was prohibited in February 2009 in line with CITES but the High Court in 2015 set aside the national moratorium on the domestic trade in rhino horn or any derivative thereof.

The challenges that arose were: Misuse of the permit system and laundering of illegally obtained rhino horn to export it legally for illegal international trade; Breaching of Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES); Inability to trace the origin of rhino horn of illegal origin; Demand for rhino horn for luxury goods and in Asia for medicine. The main medicinal distribution channel is powder or chunks, which made it difficult to monitor and to detect illegal trade as it was easy to conceal. The intervention was to strengthen existing legislation and improve the traceability of rhino horn.

Existing legislation involved:

- Threatened or Protected Species (TOPS) Regulations, which apply to all listed species;

- Rhino Marking & Trophy Hunting Norms and Standards 2009, amended in 2012 and 2018;

- CITES Regulations (regulating import, export and re-export of specimens of species)

To date, the following legislative have been addressed/strengthened:

- marking requirements;

- compulsory DNA collection and analysis;

- implementation of national database for the recording of markings, linked with a national auditing process;

- Minister to be issuing authority for all permits for selling / donating / buying / receiving of rhino horn.

The legislative gap yet to be addressed relates to specific areas / circumstances of trade.

Introduction

A permit is required in terms of NEMBA for the carrying out of any restricted activity involving rhino horn, regardless the size or form of such rhino horn. “Restricted activity” is defined in NEMBA, and includes activities such as possession, buying/ selling, hunting, killing, breeding, transporting, cutting off, etc.

The Rhino Norms and Standards require the compulsory marking of a rhino horn or a piece of rhino horn that is 5cm or longer in length, by means of a 10-digit microchip and a ZA serial number.

The draft regulatory measures on rhino horn trade include:

• Draft regulations aimed at regulating the lawful selling/ buying of rhino horn;

• Draft prohibitions, aimed at prohibiting certain activities involving rhino horn; and

• Draft listing notice, proposing the deletion of Eastern black rhinoceros from the list of invasive species, and the inclusion thereof in the list of threatened or protected species.

Calls for public comment were made in 2017 and 2018.

International trade in rhino horn for primarily commercial purposes remains prohibited by CITES.

Legislative Framework on Biodiversity

The Constitution is the highest authority which sets out environmental rights. The Constitution makes provision for the ratification of international agreements, like CITES. The legislative framework was also informed by the White Paper on Environmental Management. NEMBA was one of the specific environmental acts under NEMA. In terms of the Constitution, provinces or MECs have an equal mandate to make and implement nature conservation legislation. According to NEMBA, the Minister has the authority to make regulations, norms and standards, prohibit an activity that may negatively impact on the survival of a species and implement and publish a Biodiversity Management Plan.

Prohibitions

A person may not powder a rhino horn, or create slivers, drill bits, chips or similar derivatives, excluding under the following circumstances:

- during the insertion of a microchip or tracking device

- during the de-horning of a rhino

- when collecting a DNA sample of the horn

A person may not sell / donate / give / buy / receive or accept as donation / export / re-export, powdered rhino horn, or rhino horn smaller than 5 cm in length.

The prohibitions remain in place for a period of three years after the commencement of the notice, after which the Minister will assess and re-consider the prohibitions.

Regulations

Rhino horn may be sold only if it is 5cm or more in length. Requirements to obtain a selling permit:

- certified copy of the ID or similar document

- certified copy of the possession permit

- the rhino horn must be appropriately marked

- certified copy of the genetic profiling report

- photograph of suitable quality of each horn

- measurements (length along inner and outer curve, base circumference) and weight of each horn

- inspection by the relevant issuing authority

- recording of the information on the national database.

Prohibitions (imposed through the regulations):

- selling of rhino horn originating from other countries

- export of rhino horn through ports of exist other than OR Tambo International Airport

Requirements for online auctions:

- seller must have a selling permit at the time of bidding as the auction

- selling and buying permits must be valid for the date, or period, of the auction

- person who intends to bid at auction, must apply for buying permit at least 30 working days prior to auction.

- holder of buying permit must return permit within 5 working days of auction, if bid was not successful

- seller must provide DEFF with a list of registered bidders 48 hours prior to auction

- seller must provide DEFF with a list of successful bidders, within 5 working days of auction.

Other provisions:

- holder of selling permit may give proxy (in writing) to another person (excluding a foreign person) to sell the rhino horn (the same applies to buying)

- where a proxy applies, the seller/buyer, and the proxy holder, must be in possession of a permit

- holder of buying/selling permit must be present in the country at the time of buying/selling of a rhino horn

- seller remains responsible for safe-keeping until the possession permit of the buyer has been issued

- buyer may not take possession of the rhino horn until possession permit has been issued

- certified copy of a document remains valid for six months after the validation of the document.

Listing notice

The Eastern black rhino is removed from the list of invasive species and is included in the list of protected species in terms of NEMBA. The implications are that all these regulations and prohibitions apply to Eastern black rhino. When the listing notice commences, the TOPS Regulations and the Rhino Norms and Standards will also apply to Eastern black rhino.

Ms Boshoff asked the Select Committee to take note of the draft regulatory measures for domestic trade in rhino horn, developed in terms of NEMBA.

Discussion

Ms Labuschagne asked about the Animal Improvement Act passed in May that re-categorised wild life as farming stock. This included rhinos. Will these regulations still apply to someone who decides to farm rhinos?

Mr Cloete asked about the effect of these draft regulatory measures – was DEFF confident that provinces will still be able to make regulations specific to their provinces and that important authority would not be taken away from the provinces?

Ms Boshoff responded about the farming of animals according to the Animal Improvement Act. NEMBA and its regulations will apply alongside the Animal Improvement Act and its regulations. Provinces will still be able to make regulations according to their provincial ordinances. However, provinces have to be mindful of the constitutional requirement that all legislation needs to be aligned. When provinces do make regulations they need to ensure they are not in conflict with national legislation. NEMBA is not intended to take away the authority of provincial legislation.

Minister Creecy said that she understands that the Committee would like a little bit longer to consider the proposed regulations. She appealed to the Committee to understand that a policy vacuum exists and that these regulations were needed as soon as possible to combat the illegal trade of rhino horn.

The Chairperson thanked the Minister and her team. The minutes of the previous meeting was adopted and the meeting adjourned.

Presentation: https://pmg.org.za/files/191112Regulatory_measures.pptx

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75552

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Horn Trade

You really do the important work!

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5858

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Horn Trade

I thought it is about domestic tradeexport of rhino horn through ports of exist other than OR Tambo International Airport

Anyone here has an idea what this means?

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75552

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Horn Trade

One can never understand what their long-term plan is, Klippies. They are pathologically incapable of doing anything honestly or openly, or without personal gain, so one normally has to wait for some third party to explain or interpret.

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 66700

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Horn Trade

‘I want my horns back’ says SA rhino baron after trade deal goes pear-shaped

By Tony Carnie• 14 June 2020

A freshly-dehorned rhino at John Hume’s ranch. The horns are removed under veterinary sedation. According to wildlife vets, the operation is entirely painless, provided the operation is done by skilled professionals. (Photo: Tony Carnie)

The world’s largest rhino breeder has vowed to go to court this week to recover a massive haul of rhino horns confiscated by police after a murky trading deal turned sour in a tiny dorpie called Skeerpoort.

The 181 horns originated from the ranch of John Hume, a former property developer who has ploughed his life savings into breeding rhinos commercially to harvest and sell their horns – despite a global ban on horn trading that was imposed over 40 years ago in a bid to prevent the world’s second-largest land mammal from being poached to extinction.

Hume claims that everything was above board on his side, but the police appear to have thought there was clearly more to the deal than met the eye when they seized the stash of horns and arrested Clive John Melville and Petrus Steyn on 13 April 2019 in the isolated hamlet of Skeerpoort, about 20km from Haartebeesport Dam in North West province.

Rhino rancher John Hume is hoping to recover nearly 200 horns which were seized by police last year during a horn transaction that went sour in the town of Skeerpoort. (Photo: Tony Carnie)

Earlier this month, Melville and Steyn were fined R50,000 and R25,000 respectively after pleading guilty to charges of engaging in restricted wildlife activities without permits – to wit, possession of 181 white rhino horns of undisclosed monetary value.

Melville, 58, and believed to be related to Hume through marriage, also pleaded guilty to a further charge of forging a document to falsely authorise the transport of the rhino horns.

According to a plea and sentence agreement signed on 5 June 2020 at the Brits Regional Magistrates’ Court, Melville has been self-employed for the last 30 years and earns about R20,000 a month from buying and selling second-hand cars, and car parts.

His accomplice, Steyn, 61, is a divorced former teacher from Modderfontein who earns around R4,000 a month, working as a general labourer at a mechanical plant hire company.

The two men, who both pleaded guilty, were represented by Port Elizabeth attorney Alwyn Griebenow, who has previously represented several suspects accused of rhino poaching or rhino horn trading – including rancher Marnus Steyl and the so-called “Ndlovu gang”.

An employee at John Hume’s rhino ranch holds up two freshly removed rhino horns before they are moved to safe custody. (Photo: Tony Carnie)

Some of Griebenow’s other high-profile clients have included perlemoen poaching kingpin Morne Blignaut; murder accused Christopher Panayiotou and a group of alleged SA mercenaries arrested in Zimbabwe for plotting a coup against the government of Equatorial Guinea.

In their statement admitting guilt, Melville and Steyn acknowledge that the offences they committed related mainly to rhino horn permit transgressions – as the horns were not poached illegally and had been harvested legally from living rhinos at Hume’s ranch.

Wildlife staff at John Hume’s rhino ranch use an automatic saw to remove horns from a white rhino following veterinary sedation. (Photo: Tony Carnie)

Nevertheless, their admission of guilt statement acknowledges that “this type of offence is very prevalent” in South Africa and that the plight of the rhino was well known.

“While it is true that the horns in question were harvested legally and not through the cruel and devastating means of illegal poaching, the circumstances nevertheless show that criminals will go to great lengths to satisfy the bizarre demand for rhino horn due to the black market value thereof.”

To understand some of the complexities of the matter, it is worth recording that buying and selling rhino horns is currently legal in South Africa (subject to certain strict conditions), although selling horns commercially to buyers in another country has been prohibited since 1977 in terms of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

To complicate matters further, the legality of domestic trade in rhino horns in South Africa has undergone several changes over the past few years.

For many decades, government conservation agencies and private owners were permitted to sell horns domestically under certain conditions, but this changed in 2009, when domestic trade was banned under a government moratorium which aimed to halt rampant black-market smuggling.

Enter John Hume, a former property resort developer who currently farms more than 1,800 rhino at his ranch in North West province, and who has been lobbying to overturn the CITES ban so he can sell horns legally harvested from live rhinos to buyers in China and other Eastern nations.

(These are horns which are cut off a rhino’s head using a mechanical saw while the animal is under veterinary sedation. According to wildlife vets, the operation is entirely painless, provided it is done by a skilled professional.)

Three years ago, after a series of court battles, Hume finally managed to overturn the moratorium on the domestic sale of rhino horn.

Though this earned him the legal right to resume selling rhino horns domestically to recover some of the costs of his massive rhino ranching operation – he was still prohibited from exporting horns commercially under the CITES ban.

So, he could sell horns within South Africa (where there is no commercial consumer demand as rhino horn has never been used on a large scale for traditional medicine or other purposes) – but he was still prohibited from selling horns directly to illegal traders in China, Vietnam or Laos.

However, to test the waters and push the new legal boundaries, Hume staged a widely-publicised online, international rhino horn auction in June 2017 (with prices and buyer information translated into Mandarin and Vietnamese).

He offered 500kg of his legally harvested horns to all-comers (including foreign buyers and proxy buyers), effectively suggesting to these buyers that they could acquire his products legally. But it was, ahem, their indaba if they chose to stockpile these horns in SA until a time when the CITES ban was lifted – or well, you know, make some other kind of plan.

Returning now to the recent “Skeerpoort affair”, Hume applied to the Minister of Environmental Affairs on 7 September 2018 to sell 181 of his horns to “a certain Allan Rossouw”.

According to the court papers, the minister’s representatives later issued permit number 0-29886 to Hume (allowing him to sell the horns) and permit number 0-29888 in the name of Rossouw (allowing him to buy the horns).

A month later, the Gauteng provincial department of environmental affairs also issued rhino horn possession permit number 0-101310 in the name of Rossouw. In March 2019, a further permit application was made to transport the horns from a secure banking vault in Gauteng to another secure vault elsewhere in the province, also in the name of Rossouw.

All these permit applications were submitted by Hume’s office.

Finally, on 12 April 2019, second-hand car dealer Melville and plant hire labourer Steyn showed up at a secure banking vault where part of Hume’s stash of several tons of rhino horn are kept in custody.

According to the court papers, Melville and Steyn were acting on the instructions of Melville’s brother, Charles Melville “and/or Mr Hume”.

Hume and Charles Melville had apparently requested John Melville and Steyn to shift the horns to a place where they could be “inspected by potential buyers before negotiations regarding price could be determined by such buyers and Charles Melville and/or Mr Hume”.

The court papers do not make it clear where Allan Rossouw lives, but state that the two potential buyers who wanted to look at the horns were from Bloemfontein, and that their names and contact details were provided by Charles Melville.

To cut a long story short, John Melville and Petrus Steyn collected the horns from the vault and then drove them to an undisclosed accommodation establishment in Skeerpoort, where both men were arrested on 13 April by the police because one of the permits had been forged by John Melville and because the horns had been moved from Gauteng province to North West province, apparently without authority.

According to the Department of Environmental Affairs, the arrests were made during an operation that included members of the Hawks Serious Organised Crime and Endangered Species, Tracker SA and Vision Tactical, “following the receipt of information that a vehicle from a coastal province was carrying a considerable amount of horns. The rhino horns were allegedly destined for the South East Asian markets.”

These horns were seized by police and remain in their custody, but now Hume wants them back.

Hume, speaking through a spokesperson, had a slightly different version of events when interviewed at the weekend.

He maintained that Melville and Steyn were acting on Rossouw’s behalf when they collected the horns (not on Hume’s behalf) and that the police operation had been a “sting”.

His spokesperson said Hume’s office had notified the authorities in advance that he was about to sell some rhino horns under permit – and that he also invited them to witness the handover to the new legal buyer at the bank vault.

On Hume’s version, the authorities declined to witness the handover and opted instead to mount a sting operation which resulted in the arrest of Melville and Steyn.

And now, says Hume, he wants the horns back.

But hang on, Daily Maverick asked his office, surely the horns were no longer his, because he had already handed over the horns to Rossouw’s agents?

No, says Hume. Rossouw never paid for them – so they remain Hume’s property.

But hang on again, Daily Maverick asked, how could Hume have agreed to hand over 181 horns potentially worth many millions of rands into the custody of two men apparently acting on behalf of Allan Rossouw (if Rossouw had not paid for the horns in advance or provided adequate financial guarantees).

And, hang on once more – didn’t Hume’s office state that he had never met Rossouw in person and had only communicated with him via email.

In response, Hume’s office claims he was so desperate to conclude a legal sale that he was willing to run the risk of losing them by handing them over to the custody of a man he had never met.

Hume’s office suggested that Rossouw may have been an “agent” acting for a third party.

“Agents don’t always want you to speak directly to their clients,” his spokesperson suggested, adding that such buyers might potentially buy a product for a certain price and then sell it on at a higher price.

In any event, Hume’s office said they have now contacted the State Advocate and obtained an assurance that the horns would not be destroyed before Hume lodged an application in the High Court to recover the horns.

Good luck to the court in untangling what really went down at Skeerpoort, or the true identity and nationality of the potential end buyer.

The Hawks, the National Prosecuting Authority and Department of Environmental Affairs were all invited on Friday, 12 June 2020 to comment on Hume’s efforts to recover the horns. No response has yet been received. DM

By Tony Carnie• 14 June 2020

A freshly-dehorned rhino at John Hume’s ranch. The horns are removed under veterinary sedation. According to wildlife vets, the operation is entirely painless, provided the operation is done by skilled professionals. (Photo: Tony Carnie)

The world’s largest rhino breeder has vowed to go to court this week to recover a massive haul of rhino horns confiscated by police after a murky trading deal turned sour in a tiny dorpie called Skeerpoort.

The 181 horns originated from the ranch of John Hume, a former property developer who has ploughed his life savings into breeding rhinos commercially to harvest and sell their horns – despite a global ban on horn trading that was imposed over 40 years ago in a bid to prevent the world’s second-largest land mammal from being poached to extinction.

Hume claims that everything was above board on his side, but the police appear to have thought there was clearly more to the deal than met the eye when they seized the stash of horns and arrested Clive John Melville and Petrus Steyn on 13 April 2019 in the isolated hamlet of Skeerpoort, about 20km from Haartebeesport Dam in North West province.

Rhino rancher John Hume is hoping to recover nearly 200 horns which were seized by police last year during a horn transaction that went sour in the town of Skeerpoort. (Photo: Tony Carnie)

Earlier this month, Melville and Steyn were fined R50,000 and R25,000 respectively after pleading guilty to charges of engaging in restricted wildlife activities without permits – to wit, possession of 181 white rhino horns of undisclosed monetary value.

Melville, 58, and believed to be related to Hume through marriage, also pleaded guilty to a further charge of forging a document to falsely authorise the transport of the rhino horns.

According to a plea and sentence agreement signed on 5 June 2020 at the Brits Regional Magistrates’ Court, Melville has been self-employed for the last 30 years and earns about R20,000 a month from buying and selling second-hand cars, and car parts.

His accomplice, Steyn, 61, is a divorced former teacher from Modderfontein who earns around R4,000 a month, working as a general labourer at a mechanical plant hire company.

The two men, who both pleaded guilty, were represented by Port Elizabeth attorney Alwyn Griebenow, who has previously represented several suspects accused of rhino poaching or rhino horn trading – including rancher Marnus Steyl and the so-called “Ndlovu gang”.

An employee at John Hume’s rhino ranch holds up two freshly removed rhino horns before they are moved to safe custody. (Photo: Tony Carnie)

Some of Griebenow’s other high-profile clients have included perlemoen poaching kingpin Morne Blignaut; murder accused Christopher Panayiotou and a group of alleged SA mercenaries arrested in Zimbabwe for plotting a coup against the government of Equatorial Guinea.

In their statement admitting guilt, Melville and Steyn acknowledge that the offences they committed related mainly to rhino horn permit transgressions – as the horns were not poached illegally and had been harvested legally from living rhinos at Hume’s ranch.

Wildlife staff at John Hume’s rhino ranch use an automatic saw to remove horns from a white rhino following veterinary sedation. (Photo: Tony Carnie)

Nevertheless, their admission of guilt statement acknowledges that “this type of offence is very prevalent” in South Africa and that the plight of the rhino was well known.

“While it is true that the horns in question were harvested legally and not through the cruel and devastating means of illegal poaching, the circumstances nevertheless show that criminals will go to great lengths to satisfy the bizarre demand for rhino horn due to the black market value thereof.”

To understand some of the complexities of the matter, it is worth recording that buying and selling rhino horns is currently legal in South Africa (subject to certain strict conditions), although selling horns commercially to buyers in another country has been prohibited since 1977 in terms of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

To complicate matters further, the legality of domestic trade in rhino horns in South Africa has undergone several changes over the past few years.

For many decades, government conservation agencies and private owners were permitted to sell horns domestically under certain conditions, but this changed in 2009, when domestic trade was banned under a government moratorium which aimed to halt rampant black-market smuggling.

Enter John Hume, a former property resort developer who currently farms more than 1,800 rhino at his ranch in North West province, and who has been lobbying to overturn the CITES ban so he can sell horns legally harvested from live rhinos to buyers in China and other Eastern nations.

(These are horns which are cut off a rhino’s head using a mechanical saw while the animal is under veterinary sedation. According to wildlife vets, the operation is entirely painless, provided it is done by a skilled professional.)

Three years ago, after a series of court battles, Hume finally managed to overturn the moratorium on the domestic sale of rhino horn.

Though this earned him the legal right to resume selling rhino horns domestically to recover some of the costs of his massive rhino ranching operation – he was still prohibited from exporting horns commercially under the CITES ban.

So, he could sell horns within South Africa (where there is no commercial consumer demand as rhino horn has never been used on a large scale for traditional medicine or other purposes) – but he was still prohibited from selling horns directly to illegal traders in China, Vietnam or Laos.

However, to test the waters and push the new legal boundaries, Hume staged a widely-publicised online, international rhino horn auction in June 2017 (with prices and buyer information translated into Mandarin and Vietnamese).

He offered 500kg of his legally harvested horns to all-comers (including foreign buyers and proxy buyers), effectively suggesting to these buyers that they could acquire his products legally. But it was, ahem, their indaba if they chose to stockpile these horns in SA until a time when the CITES ban was lifted – or well, you know, make some other kind of plan.

Returning now to the recent “Skeerpoort affair”, Hume applied to the Minister of Environmental Affairs on 7 September 2018 to sell 181 of his horns to “a certain Allan Rossouw”.

According to the court papers, the minister’s representatives later issued permit number 0-29886 to Hume (allowing him to sell the horns) and permit number 0-29888 in the name of Rossouw (allowing him to buy the horns).

A month later, the Gauteng provincial department of environmental affairs also issued rhino horn possession permit number 0-101310 in the name of Rossouw. In March 2019, a further permit application was made to transport the horns from a secure banking vault in Gauteng to another secure vault elsewhere in the province, also in the name of Rossouw.

All these permit applications were submitted by Hume’s office.

Finally, on 12 April 2019, second-hand car dealer Melville and plant hire labourer Steyn showed up at a secure banking vault where part of Hume’s stash of several tons of rhino horn are kept in custody.

According to the court papers, Melville and Steyn were acting on the instructions of Melville’s brother, Charles Melville “and/or Mr Hume”.

Hume and Charles Melville had apparently requested John Melville and Steyn to shift the horns to a place where they could be “inspected by potential buyers before negotiations regarding price could be determined by such buyers and Charles Melville and/or Mr Hume”.

The court papers do not make it clear where Allan Rossouw lives, but state that the two potential buyers who wanted to look at the horns were from Bloemfontein, and that their names and contact details were provided by Charles Melville.

To cut a long story short, John Melville and Petrus Steyn collected the horns from the vault and then drove them to an undisclosed accommodation establishment in Skeerpoort, where both men were arrested on 13 April by the police because one of the permits had been forged by John Melville and because the horns had been moved from Gauteng province to North West province, apparently without authority.

According to the Department of Environmental Affairs, the arrests were made during an operation that included members of the Hawks Serious Organised Crime and Endangered Species, Tracker SA and Vision Tactical, “following the receipt of information that a vehicle from a coastal province was carrying a considerable amount of horns. The rhino horns were allegedly destined for the South East Asian markets.”

These horns were seized by police and remain in their custody, but now Hume wants them back.

Hume, speaking through a spokesperson, had a slightly different version of events when interviewed at the weekend.

He maintained that Melville and Steyn were acting on Rossouw’s behalf when they collected the horns (not on Hume’s behalf) and that the police operation had been a “sting”.

His spokesperson said Hume’s office had notified the authorities in advance that he was about to sell some rhino horns under permit – and that he also invited them to witness the handover to the new legal buyer at the bank vault.

On Hume’s version, the authorities declined to witness the handover and opted instead to mount a sting operation which resulted in the arrest of Melville and Steyn.

And now, says Hume, he wants the horns back.

But hang on, Daily Maverick asked his office, surely the horns were no longer his, because he had already handed over the horns to Rossouw’s agents?

No, says Hume. Rossouw never paid for them – so they remain Hume’s property.

But hang on again, Daily Maverick asked, how could Hume have agreed to hand over 181 horns potentially worth many millions of rands into the custody of two men apparently acting on behalf of Allan Rossouw (if Rossouw had not paid for the horns in advance or provided adequate financial guarantees).

And, hang on once more – didn’t Hume’s office state that he had never met Rossouw in person and had only communicated with him via email.

In response, Hume’s office claims he was so desperate to conclude a legal sale that he was willing to run the risk of losing them by handing them over to the custody of a man he had never met.

Hume’s office suggested that Rossouw may have been an “agent” acting for a third party.

“Agents don’t always want you to speak directly to their clients,” his spokesperson suggested, adding that such buyers might potentially buy a product for a certain price and then sell it on at a higher price.

In any event, Hume’s office said they have now contacted the State Advocate and obtained an assurance that the horns would not be destroyed before Hume lodged an application in the High Court to recover the horns.

Good luck to the court in untangling what really went down at Skeerpoort, or the true identity and nationality of the potential end buyer.

The Hawks, the National Prosecuting Authority and Department of Environmental Affairs were all invited on Friday, 12 June 2020 to comment on Hume’s efforts to recover the horns. No response has yet been received. DM

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5858

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Horn Trade

Rhino horn trade – Tourism & conservation leaders lobby SA minister Creecy

Posted on June 17, 2020 by Team Africa Geographic in the OPINION EDITORIAL post series.

Rhino horn trade: Leading figures from the African tourism and conservation industries have signed a detailed reply to the advisory committee of South Africa’s Minister of the Environment Barbara Creecy in response to her call for submissions relating to the ongoing review by the committee of trade in elephant, rhino, lion and leopard. This submission has been confirmed as having been received by the committee on Monday 15 June 2020.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

To the Chairperson of the Advisory Committee, Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries

15th June 2020

Dear Chairperson and Advisory Committee:

Ref: Response to Notices 221 and 227 in Government Gazette Nos 43173 and 43332 – Submission to the Advisory Committee appointed by the Minister to review the existing policies, legislation and practices related to the management, handling, breeding, hunting and trade of Elephant, Rhino, Lion and Leopard.

This submission responds to the call for submissions issued by the Minister’s Advisory Committee in the Government Gazette as detailed above. It deals specifically with the trade in Rhino horn, although the points made apply equally to important aspects of the Elephant, Lion and Leopard categories.

Before addressing our points, however, we wish to highlight that the Notices (page 1) call for submissions “to review existing policies, legislation and practices relating to the management and breeding, handling, hunting and trade of …. Rhinoceros.” However, the Terms of Reference for the Committee acting as the High-Level Panel (HLP) stipulate (page 3) that it is tasked to:

“… make recommendations relating to….

• Develop the Lobby/Advocacy strategy for Rhino horn trade in different key areas including, but not limited to: …..Identification of new or additional interventions required to create an enabling environment to create an effective Rhino horn trade.”

This clearly indicates that a policy on the trading of Rhino horn has already been decided and that this call for submissions is simply about developing a lobbying and advocacy strategy to facilitate its implementation.

We strongly object to the framing of the call for submissions in this way. No such policy on trade in Rhino horn has been agreed to and it is illegal in terms of international legislation. The wording of the call clearly goes against the spirit of current legislation and begs serious questions as to its underlying purpose.

The remainder of our submission is directed at illuminating the extremely damaging consequences of any legalisation of the trade in Rhino horn – for South Africa’s wild Rhino population, for South Africa’s global tourism offering, and for the large number of poor households who live in the proximity of the country’s Big Five wildlife reserves.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

We organise our submission under the following points:

1. The important role of markets – and market failures – in determining conservation outcomes

a) We want to state clearly that the authors of this submission are strong supporters of market-based solutions to conservation challenges. Through the price mechanism and in normal circumstances, free markets have an unrivalled power to incentivise producers and consumers of goods and services to invest and act in ways that maximise positive social (including conservation) outcomes, in their pursuit of private profit. The thriving private lodge industry within and along the borders of our national and provincial parks, the large numbers of predominantly unskilled people it employs and the associated abundance of wildlife there bears ample testimony to this reality.

b) However, ‘market failures’ can occur in any system. As a result of these, the alignment between private and social returns can break down in various ways. When this divergence happens the outcomes of market processes can be extremely damaging and long-lasting. We believe that, for reasons that this submission will outline, fundamental and enduring market distortions and failures underpin the global market for Rhino horn. As a result, any move to legalise this trade, however small and seemingly insignificant on the face of it, will have disastrous consequences for the survival of Rhinos in the wild – both in South Africa and globally.

c) Although the market for elephant ivory, lion bone and leopard products differ in important respects from Rhino horn and from one-another, similar market failures apply in these areas too.

2. The demand and supply characteristics of the global market for Rhino horn and their consequences for conservation

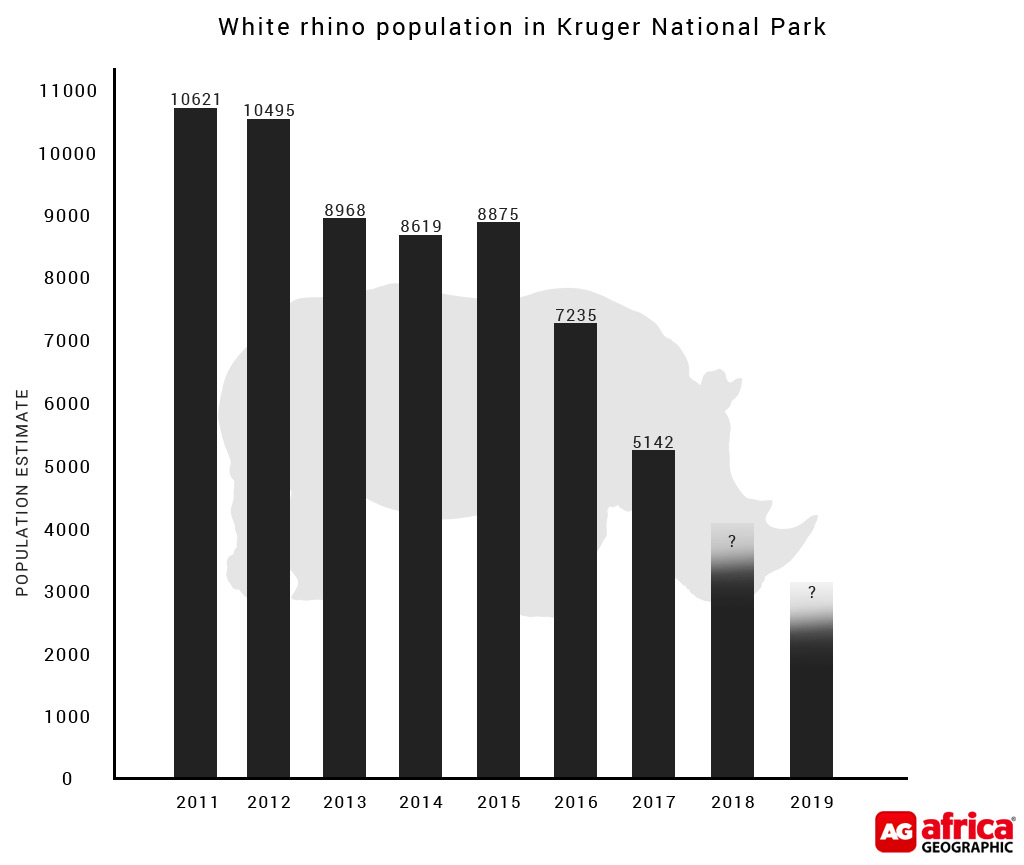

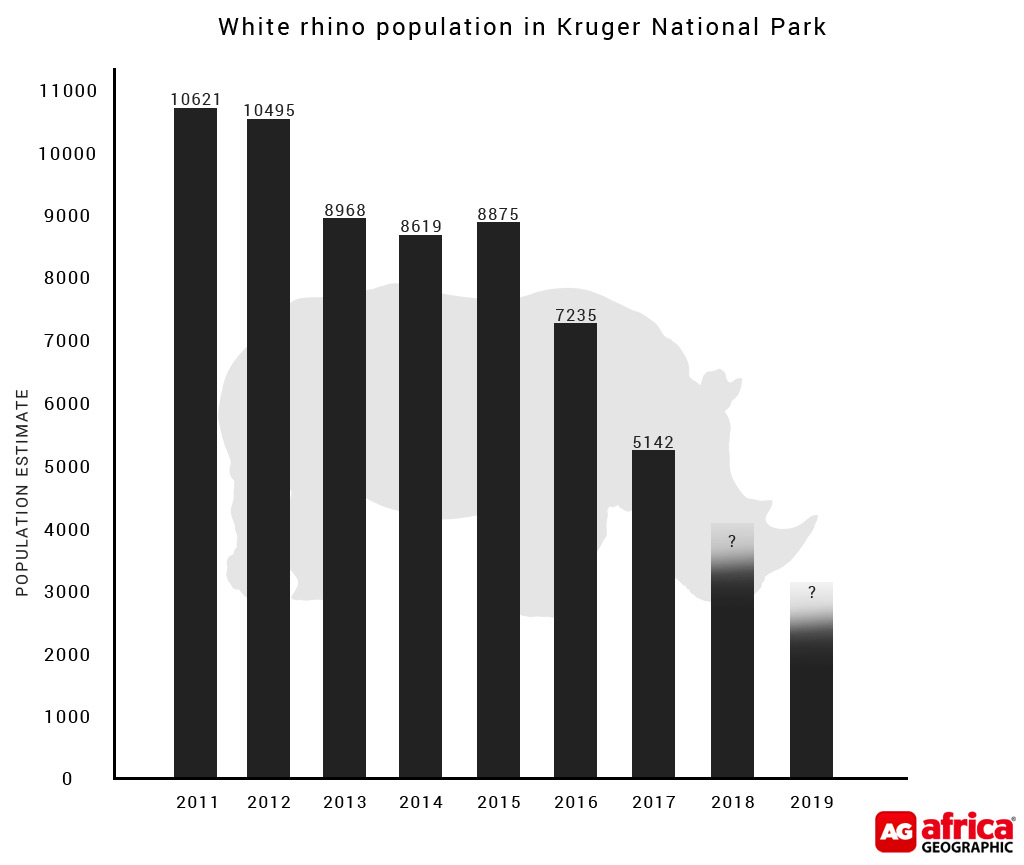

a) Demand: In the absence of a legal market for horn, it is impossible to accurately determine the extent or value of global demand. Estimates drawn from pan-African Rhino poaching statistics in the late 1970s suggest that the Asian demand for horn amounted to between 45 tons and as high as 70 tons per year (*1). Since then China has banned the trade and consumption of Rhino horn for use in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)which did dampen demand. But this has subsequently been at least matched by the growth in demand from neighbouring countries, in particular Laos, Vietnam (and now again in China) where the middle and upper classes have expanded enormously over this period. The North Korean state has also clandestinely entered the market for Rhino horn via its Embassies, which uses horn to boost its scarce foreign exchange reserves. It is not unreasonable therefore to assume that global demand could rapidly expand back to the 45 to 70 tons range per year if trade was legalised and demand was re-stimulated (often as a result of the signal that legalisation sends to the market).

*1 The total number of rhinos in Africa in 1978 was 65,000. The total rhino population in 1987 had plummeted to just 4,000. (Reference: John Hanks Operation Lock page 38 and many journals from that era). 61,000 rhinos were poached in just 9 years, equating to an average of 6,777 rhinos poached each year for each of those 9 years. Average horn set sizes in those days was around 7kgs per rhino which would equate to an average of 47 tons of rhino horn poached each year for 9 years. But towards the end of this period the rhino population was already below 6,777, meaning that a lot more rhinos had to have been poached in 1978 because they were more numerous. Statistically we can therefore calculate that around 70 tons of rhino horn were poached a year in that period around 1978.

b) Supply: A study conducted by the then Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) in 2014 confirmed that the amount of Rhino horn that South Africa could make available annually and sustainably from shavings of farmed Rhino, from existing stocks and future mortalities was then around 2 tons a year, climbing to a maximum of 5 tons a year based on intensive efforts to breed Rhinos (*2). An estimated 16,000 Rhinos exist in SA today, of which maybe around 15% (+2,500) are farmed and the rest are found in our national parks, provincial and private game reserves.

c) The Demand/Supply mismatch and its consequence: Given the enormous gulf that exists between the global potential demand for Rhino horn and the actual maximum possible legal supply – even through intensive breeding and farming – any legalisation of its trade could immediately result in increased actual demand. Assuming intensive captive breeding succeeded in growing the overall supply of horn (i.e. both farmed and wild-deceased) by 10% per year (in itself a highly optimistic assumption), it would take at least thirty five years for the Rhino farming industry to meet the lower level (40 tons p.a.) of this potential annual demand range. The supply lag would take much longer to bridge if (as is highly likely) market demand increased from current levels following legalisation.

As a result, one can anticipate overwhelming demand pressure on any regulated horn supply channel for many years, with obvious inflationary consequences for prices across the board. This would inevitably lead to increased poaching levels of wild Rhinos to meet that demand and to capitalise on the high prices. Instead of helping to reduce poaching levels, legal supply of Rhino horn into the market, however small, would directly incentivise increased poaching of wild Rhinos. As is clear from the evidence, the poaching of wild rhinos is always less expensive than breeding and dehorning (*3). Beyond its impact on the species, this would put SA’s tourism industry, its many related jobs in rural areas and its international reputation at enormous risk.

Some commentators view the spike in prices that would result from legalisation as an opportunity for the SA Government to realise a greater return from its stockpiled reserves, thereby easing its budgetary constraint and enabling enhanced investment in conservation. This is a fallacious and self-defeating argument which would be extremely short-sighted and reckless in light of its consequences for Rhinos in the wild.

*2 https://www.environment.gov.za/sites/de ... report.pdf

*3 Douglas J Crookes and James N Blignaut, “Debunking the Myth That a Legal Trade Will Solve the Rhino Horn Crisis: A System Dynamics Model for Market Demand,” Journal for Nature Conservation 28 (November 2015): 11–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2015.08.001.

d) Rhino horn price considerations and their consequences: The peak prices that Rhino horn has sold for in the early 2000’s have been around US$60,000 per kilogram, at one point flirting with US$100,000/kg in response to speculative activity. The black-market price for Rhino horn has subsequently dropped to between US$15,000 to US$20,000/kg currently. If demand is re-stimulated, as a result of South Africa legalising the sale of even a portion of its horn stockpile, the black-market price could well revert back to US$60,000 as the market would likely be reactivated.

South Africa’s Private Rhino Owners’ Association (PROA) has proposed a selling price for stockpiled horn in a range between US$10,000 and US$23,000 per kilogram (*4). This translates into a potential premium of the black-market price over regulated supplies of US$ 3,000 to US$ 5,000 (i.e. 15% – 50%) per kilogram. Regardless of the premium, formalising the market at these selling prices would signal the opportunity for massive profits to be made through poaching which is associated with low costs relative to farming (*5).

Given the growth in demand that will undoubtedly follow legalisation and the continuing constrained supply, the price differential between legal and illegal horn supplies will only increase– in both the short and long-term. The price elasticity of demand for Rhino horn (i.e. the extent to which price increases result in a reduction in demand) is demonstrably very low, implying an almost insatiable demand for horn at even the most constrained supply and high price scenarios. Similarly, the price elasticity of supply for horn (the extent to which supply is able to increase in response to higher prices) is low, given the reproduction rates for farmed Rhino (*6).

A context of high demand and constrained legalised supply is a recipe for sustained upward pressure on the price of Rhino horn. This will further incentivise black- market activity aimed at capitalising on rising prices, which will directly manifest in increased poaching. From this, it is clear that, the legalisation of trade will immediately trigger a spiral of black-market activity and poaching, which will not stop for as long as demand exceeds supply – i.e. for many decades. It also runs the risk of driving up speculator activity, where banking on extinction becomes an attractive strategy (*7).

*4 PROA submission to the Advisory Committee of the HLP, 27 May 2020.

*5 Douglas J Crookes, “Does a Reduction in the Price of Rhino Horn Prevent Poaching?,” Journal for Nature Conservation 39 (2017): 73–82, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2017.07.008.

*6 Crookes and Blignaut, “Debunking the Myth That a Legal Trade Will Solve the Rhino Horn Crisis: A System Dynamics Model for Market Demand.”

*7 Charles F. Mason, Erwin H. Bulte, and Richard D. Horan, “Banking on Extinction: Endangered Species and Speculation,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 28, no. 1 (2012): 180–92, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grs006.

e) The wealth, power and global reach of the criminal syndicates that control the illegal horn trade: The final characteristic of the global Rhino horn market is its control by extremely wealthy, pervasive and corrupt criminal enterprises. These effectively oversee every link in the supply chain, from the point of harvest to trans-shipment, processing and final sale.

The illegal horn trade is in effect a globally integrated supply chain controlled by extremely rich, agile and powerful criminal syndicates which frequently run parallel enterprises in other wildlife products, narcotics, human trafficking and the like. In this respect it is not dissimilar to the ivory trade (*8). The leverage extends across the regulatory and criminal justice systems that the exposed governments will deploy to oversee any future legal trade.

In the face of these syndicates, the effectiveness of the statutory bodies charged with policing the trade now and in the future are likely to be poor. Under- resourced, weak and vulnerable to corruption at the best of times, these agencies will not be able to hold out against the inducements, intimidation and violence of the interests that control the black market once (if) the lucrative arbitrage opportunities emerge between the illegal and legal trade channels. History clearly shows (see discussion further below) that it is inconceivable for any regulated channel established to control the legalised trade in horn to retain its integrity and not be contaminated by supply from unregulated (illegal) sources given the latter’s wealth and willingness to use it for persuasion (*9).

*8 Ross Harvey, Chris Alden, and Yu Shan Wu, “Speculating a Fire Sale: Options for Chinese Authorities in Implementing a Domestic Ivory Trade Ban,” Ecological Economics 141 (2017): 22–31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.05.017.

*9 Laura Tensen, “Under What Circumstances Can Wildlife Farming Benefit Species Conservation?,” Global Ecology and Conservation 6 (2016): 286–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2016.03.007; Elizabeth L. Bennett, “Legal Ivory Trade in a Corrupt World and Its Impact on African Elephant Populations,” Conservation Biology 29, no. 1 (2014): 54–60, https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12377.

f) The consequences of the legalisation of Rhino horn trade on Rhino poaching: Given the supply, demand and price characteristics of the global Rhino horn market, the price disparity between legal and illegal supplies of horn will at the very least continue following the legalisation of any aspect of the trade (*10). This, in turn, will lead directly and without delay to the following:

i. An overwhelming incentive for the criminal syndicates that control illegal supplies of horn to increase their procurement through poaching and related illicit marketing activities, so as to arbitrage the price differential between legal and illegal channels on top of realising the standard large profits from exploiting the difference between the selling price of horn and the cost to poach that horn(*11).

ii. An overwhelming incentive on behalf of poachers at the bottom of the illegal supply chain, most of whom are poor and lack alternative livelihood opportunities, to engage in poaching so as to realise as much value from the neighbouring wildlife resource – regardless of its consequences.

iii. A dramatic acceleration in the poaching of wild Rhinos globally, to the point where they will rapidly disappear outside of small, protected farms and zoos. Is this how tourists will want to view Rhinos when they visit South Africa?

The recent dramatic rise in rhino poaching in Botswana’s Okavango Delta demonstrates how quickly conservation efforts can dissipate when demand is stimulated. The threat from poaching is severe enough to the extent that Botswana is now moving all its last remaining black rhino from the wild to a safe haven well away from the Okavango Delta. Botswana will again have no black rhinos in the wild.

This outcome will be inevitable and unavoidable in South Africa if any aspect of the Rhino horn trade is legalised.

*10 Alejandro Nadal and Francisco Aguayo, “Leonardo’s Sailors: A Review of the Economic Analysis of Wildlife Trade” (Manchester, 2014).

*11 Ciara Aucoin and Sumien Deetlefs, “Tackling Supply and Demand in the Rhino Horn Trade” (Pretoria, 2018), https://enact-africa.s3.amazonaws.com/s ... ldlife.pdf.

3. Taking account of the lessons from previous legalisation experience

Beyond what market forces dictate will happen, there is clear evidence to be drawn from past experience of what happens when trade in Rhino horn and elephant ivory is legalised, even partially.

a) The 1993 Rhino horn ban: In a little more than a decade leading up to the Pelly Amendment that led to the full ban on Rhino horn trade in 1993, poaching of Rhinos had decimated the African population from 65,000 (1978) to around 4,000 (1987). Within one year of the full implementation of the worldwide trade ban, demand for Rhino horn plunged, resulting in the incidence of Rhino poaching plummeting to insignificant and manageable levels. The ban worked and the beneficial consequences of the trade ban resulted in over ten golden years for Rhinos – up until the mid-2000s. That was when loopholes in CITES hunting/shipment legislation (by uplifting Southern Africa’s white rhinos to Appendix II etc) were exploited by Vietnamese and other criminal syndicates. The resultant supply immediately re- catalysed demand and reactivated a broader supply chain. This led to the recent rapid and uncontrolled escalation in poaching at enormous cost to both public and private park authorities.

b) The 2008 partial lifting of the elephant ivory ban: Following the precipitous decline in Africa’s elephant population in the 1970s and 80s, a total, loophole proof CITES ivory trade ban was implemented in 1990. Demand for ivory plummeted immediately, and from 1990 for the next fifteen years or so, poaching across Africa diminished to insignificant levels allowing populations to recover. In 2008 CITES gave Southern African states permission to sell 108 tons of ivory to China and Japan. The supply of even small volumes (2 tons per year, in the case of China) into the legal domestic carving market immediately provided the cover for the criminal syndicates to launder illegal, poached ivory into the legal market channel. At the point of sale, there is no means of distinguishing legal from illegal ivory, and very few market players have an interest in finding out. The upshot was that the southern Africa ivory sale re-catalysed the market and demand for ivory in China which in turn triggered a dramatic escalation in poaching in central and west African elephant populations (and Tanzania in particular), where between 20,000 and 30,000 elephants were poached annually across Africa. However, since the Chinese government banned domestic ivory trade at the end of 2017, demand for ivory has dropped and raw ivory prices have plummeted from a high of $2,100/kg in 2014 to around $700/kg today. And with that poaching levels around Africa are starting to ease again.

c) The lessons are clear: even a very proscribed legal trade in an extremely scarce commodity for which there is strong potential demand will dramatically activate that demand by both legitimising the use of that product and catalysing a market for its distribution. This immediately incentivises criminal syndicates to enter the supply chain to profit from laundering their cheaper, illegally procured product into the legal market. Banning all legal trade universally; closing all legal loopholes; eliminating the mixed messages that accompany ongoing debates around legalisation and sending a strong message to the market that all product is illegal in any form, are thus the only means of effectively killing the demand for Rhino horn (and ivory etc). This, in turn, is the only effective means of reducing the threat imposed by poaching to the survival of the species in the wild (*12).

4. The damaging consequences of legalisation for tourism

Pre-Covid, South African tourism had emerged as a key component of a strategy to realise inclusive economic growth. Given its broad base, low entry barriers, high number of women employed (i.e. high number of dependents) and geographical dispersion across deep rural areas, tourism presents a unique opportunity for small business creation, low-skilled labour-intensive growth and enhanced foreign exchange earnings. Up to 80% of international tourists to SA are drawn by South Africa’s wildlife offer in tandem with the Cape. Market research has shown that these tourists are overwhelmingly opposed to hunting and / or trade in endangered species and products in line with global trends. Tourism would be gravely affected if we were to lose our Rhinos in the wild – i.e. if SA would became a ‘Big Four’ safari destination (*13). The attractiveness of South Africa as a safari destination would be seriously and negatively compromised by any move to legalise the Rhino horn trade.

Both the public sector and the private sector of South Africa’s wildlife economy are overwhelmed by the costs associated with anti-poaching security. Any legalisation of the Rhino horn trade would immediately exacerbate these costs as poaching levels would escalate to even higher levels than the current situation as the demand for illegal horn would ramp up to meet the high value market- arbitrage and / or profit opportunities that would emerge from legalised trade.

The appeal from this submission to the HLP is to recognise that it is far more prudent and rewarding for the SA Government to invest in the protection and re-growth of the traditional tourism industry which at its pre-Covid peak was worth over R120 billion annually (and supported the livelihoods of one in seven South Africans), than risk much of that to support an unproven industry that is worth less than 1% of that and will benefit a very small number of people.

Post-Covid, Brand South Africa must cultivate to successfully capitalise on the re-emergence of the global travel market is that of an ethical wildlife destination, uncompromised by any associations with criminality and exploitation. These negative associations will unavoidably accompany any legalisation of the Rhino horn trade.

*12 Ross Harvey, “Risks and Fallacies Associated with Promoting a Legalised Trade in Ivory,” Politikon, June 27, 2016, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1080/02589346.2016.1201378; Harvey, Alden, and Wu, “Speculating a Fire Sale: Options for Chinese Authorities in Implementing a Domestic Ivory Trade Ban.”

*13 Clarissa van Tonder, Melville Saayman, and Waldo Krugell, “Tourists’ Characteristics and Willingness to Pay to See the Big Five,” Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences, 2013, www.stoprhinopoaching.com.

5. The alternatives to legalisation

There is only one alternative to the legalisation of any aspect of the Rhino horn trade, and that is an absolute ban on the trade globally and domestically, in any and all of its manifestations.

If the Government wanted to be really innovative and raise considerable amounts of money for South Africa’s fiscus to fund the running costs of South Africa’s National Parks and provincial game reserves, this ban should be accompanied by the destruction of existing publicly and privately held rhino horn stockpiles. This could be undertaken through a widely publicised, high profile, celebrity-endorsed Rhino horn ‘burning event’ in the Kruger National Park (*14). This could serve as a worldwide rallying and fund raising event to raise money for conservation by asking the world to ‘buy’ the rhino horn that was about to be burnt through donations both big and small. The money raised would be shared proportionally between SANParks and the private sector according to their respective horn contributions to the burn. This event would also create much needed positive worldwide publicity for South Africa that would enhance our ethical brand and entice many more tourists to visit the country. Such an event would be an unequivocal win for all stakeholders – Rhino conservation, for SA’s parks, for tourism to South Africa and for SA’s fiscus.

Importantly, the Burn in tandem with a significant worldwide demand reduction campaign would simultaneously send a powerful message to Rhino horn traders, processors, criminals and consumers alike that there is no prospect of ever sourcing horn supply on any meaningful scale, and that Rhino horn no longer had any value. While this would obviously not completely stop the illegal trade in and use of horn, it would:

1. eliminate once and for all the mixed messaging and the associated forward planning by the black-market participants in the supply chain, in anticipation of some form of trade relaxation, and as a direct result

2. reduce poaching considerably to manageable levels (along the lines of the 1993 ban on rhino horn trade) to well below the birth rates of Rhinos in the wild.

Together with more, and more effective, demand management initiatives in Asian markets– including the post-Covid attention and commitment that will undoubtedly be directed by governments and agencies at eliminating the trade and sale of wild animals – these actions offer the best prospects of permanently eliminating the market for horn. Only through these interventions and their market-collapsing outcomes will the future of Rhinos in the wild be secure (*15).

*14 Chris Alden and Ross Harvey, “The Case for Burning Ivory,” Project Syndicate, 2016,

*15 Ross Harvey, “South Africa’s Rhino Paradox,” Project Syndicate, 2017

6. The urgent need for clear and consistent communication by the SA Government

We cannot over-emphasise the extremely damaging consequences for Rhino conservation of the on- going debates – and the mixed messages that they feed across the value chain – around legalisation of the trade in horn. Just as any form of legal trade may stimulate demand by legitimising the use of the product, continued mixed messaging which references the scope for future trade (on whatever scale), keeps the supply chain and its participants alive: exploring loopholes, raising stockpiles, lobbying stakeholders, corrupting security personnel and paying poachers.

7. Dispelling some of the myths deployed by the lobby for legalisation of trade

A number of enduring ‘logical’ sounding myths have been created and continue to be perpetuated to bolster arguments to legalise trade of Rhino horn, elephants, lions and leopards. These myths are highlighted and answered briefly, in no particular order, below. We urge the Panel not to be persuaded by any of these unfounded arguments.

a) Ostriches and crocodiles were saved from extinction through commercial farming- their success should be replicated and applied to Rhinos via the commercialisation of the horn trade and the promotion of Rhino farming.

There are no parallels between the crocodile/ostrich value chains and Rhinos, and therefore no lessons to be drawn to support the legalisation of trade in horn. Female ostriches can produce upwards of 40 chicks per year and crocodiles around 60 hatchlings per year which compounded over five generations equates to over 100 million animals. A mature female Rhino will produce one calf every two and a half years and very few over her lifetime. Starting from the current stock of farmed animals, commercial Rhino farming will, on very optimistic assumptions, take at least 30 years to meet current levels of demand. Given the huge disparity between demand and supply for horn and its impact on prices, Africa’s wild Rhinos will be extinct well before the point when stocks of farmed Rhino are remotely able to satisfy world demand. Moreover, Asian consumers prefer wild over farmed products when there is a medicinal use because of the belief that wild products have more potency (*16). Commercial farming of Rhinos thus offers no solution to the poaching crisis.

b) Exclusive government to government selling channels can be established to regulate trade and neutralise the black market.

The countries most likely to be involved in such arrangements have a very poor record with regard to enforcement. The integrity of these channels will never be maintained in the face of the sustained attack that will be directed at them from rich and generous criminal syndicates, many of which have infiltrated these organisations anyway. As has been illustrated, the establishment of legal trade channels does nothing to displace illegal channels. On the contrary, it incentivises their expansion. Illegal supply channels are difficult enough to police effectively. This ask is made all the more difficult when they are given cover by parallel legal channels whose end-markets are indistinguishable (*17).

*16 Tensen, “Under What Circumstances Can Wildlife Farming Benefit Species Conservation?”

*17 Alan Collins, Gavin Fraser, and Jen Snowball, “Issues and Concerns in Developing Regulated Markets for Endangered Species Products: The Case of Rhinoceros Horns,” Cambridge Journal of Economics 40, no. 6 (2016): 1669–86, https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bev076.

c) Funds raised through commercial farming and trade can be used to finance conservation and community development.

Beyond the minimal growth in labourer level employment that could result from increased farming (if any), there will be very little benefit for communities that live around South Africa’s wildlife reserves or for conservation programmes – or for the national treasury. One must ask whether sable, buffalo colour variant breeding, Rhino or other game farming has ever materially benefited communities or conservation around South Africa’s national parks?

But those activities have clearly created genetic risks and undermined the country’s reputation (*18). Moreover, as was revealed by the sale of ivory stocks in 2008, the proceeds of such sales do not get ring-fenced within treasury for ploughing back into conservation, security and ‘community development’ as is so often alleged. They are absorbed into the general appropriation account.

d) There are parallels to be drawn between banning trade in Rhino horn and banning sales of cigarettes during Covid19 – bans will never be effective.

There are no parallels between Rhino horn bans and cigarette or alcohol bans. The latter are widely consumed, repeat-use, involving habits which, within certain regulatory limits, are fully legal. Banning them will give rise to widespread popular resistance and rampant black-market transactions. Rhino horn trade and use is limited to specific market niches globally, beyond which they are widely shunned. While banning all trade in and the use of Rhino horn will possibly result in some initial black market activity, this will be on an insignificant and diminishing scale the longer the ban and the attendant demand reduction campaigns and negative social messaging is maintained (*19). It should be remembered that history has proven that loophole free rhino horn (and ivory) trade bans have indeed worked.

e) We should pursue a pilot project around legalisation. If it doesn’t work the ban can be re-imposed.

We already know from past experience that legalising trade, whether in horn or ivory, does not stop poaching; it accelerates it. If South Africa sold Rhino horn to the Asian market for a few years with a view to stopping if those sales did not stop poaching, the effects on our wild Rhino populations would be devastating. The few years of legal sales will serve merely to create the long-term cover under which the trade in poached Rhino horn will thrive. SA’s once-off ivory sale to China in 2008 proved that once a legal market exists, the legally obtained tusks provided lengthy legal cover for poached ivory to be easily laundered into the market masquerading as the legal product (*20). Fundamentally, as we know, there are not enough Rhinos in the wild to start recklessly testing unproven pro-trade economic models in complex, fast growing and corrupt Asian markets with rapidly increasing numbers of wealthy consumers. By the time the unintended (but entirely predictable) consequences of legalisation are recognised, and steps taken to reverse them, there is every likelihood that the world will have lost its wild Rhino population. Forever.

*18 Jeanetta Selier et al., “An Assessment of the Potential Risks of the Practice of Intensive and Selective Breeding of Game To Biodiversity and the Biodiversity Economy in South Africa,” 2018.

*19 https://theconversation.com/what-is-the ... -it-136337, accessed 14 June 2020.

*20 Harvey, Alden, and Wu, “Speculating a Fire Sale: Options for Chinese Authorities in Implementing a Domestic Ivory Trade Ban.”

8. Conclusion

We trust that this submission and the comparative global experience it draws on shows beyond any doubt that the legalisation, even partially or temporarily, of any aspect of the global Rhino horn trade will do immediate and lasting damage to the prospects for the survival of Rhinos in the wild.

Similarly, selling or auctioning off existing stockpiles of Rhino horn is not a viable option to solve our Rhino poaching scourge. If South Africa did trade its Rhino horn, a handful of players who control existing stockpiles and who control the global supply chain would become very wealthy. But this would be at the expense of SA’s wild Rhino population whose demise may follow very quickly as the global market expanded and as the criminal syndicates who control it set about arbitraging the price differentials between any regulated market and the international black market.

In a nutshell, the specific demand, supply and criminal characteristics of this market mean that even a partial legalisation of trade in horn will create massive poaching pressure on the remaining wild population which will be impossible to contain.

The time has come for the Minister to take a pragmatic decision for the long term benefit of Rhinos in the wild, for South African tourism and for the rural communities whose livelihoods depend on the wildlife economy of banning outright all trade forever in all Rhino horn and ivory (and indeed lion and leopards).

In the light of the evidence, we urge the DEFF to entrench the ban on any trade in Rhino horn both domestically and internationally. We also urge it to be bold in communicating a single, unambiguous message to the world: that it will not countenance any change in this policy. There would be no more effective way to communicate this message and effectively eliminate any speculation in the market regarding future sales, for it to publicly destroy its available Rhino horn stockpile.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

References and further reading:

Alden, Chris, and Ross Harvey. “The Case for Burning Ivory.” Project Syndicate, 2016.

Aucoin, Ciara, and Sumien Deetlefs. “Tackling Supply and Demand in the Rhino Horn Trade.” Pretoria, 2018. https://enact- africa.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/2018_03_28_PolicyBrief_Wildlife.pdf.

Bennett, Elizabeth L. “Legal Ivory Trade in a Corrupt World and Its Impact on African Elephant Populations.” Conservation Biology 29, no. 1 (2014): 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12377.