Re: Fossils

Posted: Wed Dec 07, 2022 7:12 pm

A past buried in the Karoo town of Sutherland holds portents for our survival as a species

Seed cones of the Glossopteris plant preserved with its pollen cones, solve a 200-year-old botanical mystery as to the reproduction of the long-extinct plant which formed most of the economically important coal reserves used today, says Dr Rose Prevec. (Photo: Rose Prevec)

By Jamie Venter | 6 Dec 2022

The discovery of exquisitely preserved plant and insect fossils may shed light on previously unknown life of the past. But these tiny fossils may have an even bigger story to tell: the story of a mass extinction believed to have been driven by greenhouse gas emissions that draw an eerie parallel to today’s climate crisis.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Sutherland is well known for its great expanse of fossil fields, which are littered with the bones of dinosaurs that once roamed the landscape. It is also known for being cold — really cold. This reputation is well-earned, but the large reptilian remains of life before humans make the Karoo’s bitter cold worthwhile for tourists and palaeontologists alike.

Just a short way out of town, on a small site no larger than six by five metres, thousands of remarkably well-preserved fossilised plants, birds and insects may hold the key to understanding extinction events of the past and assist scientists in predicting the effects of the current climate crisis. This is according to new research conducted by paleobotanist Dr Rose Prevec.

“Sutherland is known for its vertebrate fossils; the bones preserve really well in that area,” said Prevec. But despite attempts to locate evidence of fossilised plant life in the area, there have been very few well-preserved discoveries. This is because the soft tissues that predominantly make up plants and insects tend not to fossilise at all, except under very unique circumstances.

‘Miraculous’ find

“It was really miraculous to find any plants, let alone something so beautifully preserved,” said Prevec.

The site — which was originally discovered in 2009, but on which excavations only began in 2016 due to a lack of interest in funding the dig — has unearthed thousands of plant and insect fossils, some of which are new to science.

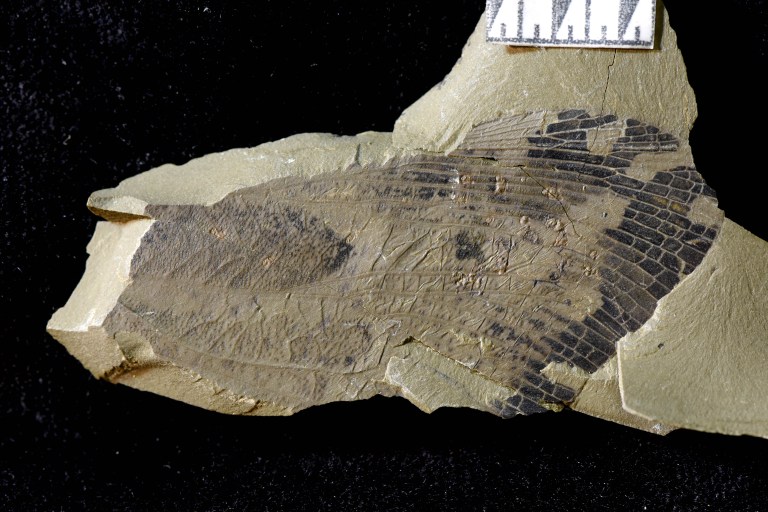

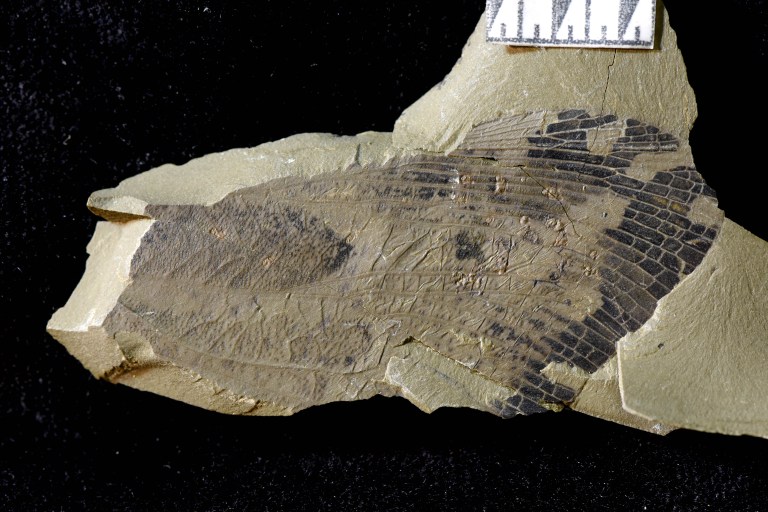

This 40-million-year-old fossilised leech found in the Karoo could be the oldest freshwater leech discovered, says paleobotanist Dr Rose Prevec. (Photo: Rose Prevec)

The fossils unearthed reveal life that existed in a lakeshore ecosystem, 266 million years ago, states the research paper.

Some of the discoveries include a fossilised leech, mosses, liverworts, winged insects, mites and leaves of plants such as Glossopteris, which formed most of the economically important coal reserves used today.

The leech may be the oldest freshwater leech in the world and is dated as far back as 40 million years, explains Prevec.

Although the fossils may be small, they are compelling.

When the researchers found the first mite, they believed it to be a seed, explains Prevec. But, “we looked closer and these legs appeared and it was this giant tick-looking thing. And then there was a lot of excited shrieking,” says Prevec.

“These fossils are important because they fill in a gap in the fossil record,” says Prevec.

Currently, scientists have a good idea of the vertebrate animals that existed because they preserve so well and are found in abundance, but there is very little understanding of the plant and insect life from the same ecosystems.

The discoveries of these fossils will help fill in the gaps in scientists’ understanding of evolution of these insects and plants, explains Prevec.

This is an important gap to fill, because, as well as contributing to scientists’ understanding of evolution, it also has implications for current climate change research.

To understand an “ecosystem, measure biodiversity and how it changed with shifting climates, we need to look at the small things and the green things”, says Prevec.

“If you were to study a modern ecosystem and wanted to understand climate change, you wouldn’t look at six antelope and a lion,” says Prevec.

“It’s really the plants, the insects, the small things, the things that are at the base of the food chain, that really tell you what’s going on with an ecosystem.”

Thousands of remarkably well preserved fossilised plants, birds and insects were discovered in the Karoo, some of which showed intact wings, hairs and even coloration. Such well preserved invertebrate fossils, as pictured above, are extremely rare to find, says paleobotanist, Dr Rose Prevec. (Photo: Rose Prevec)

Understanding this ecosystem and the fossils it left behind is particularly important because of their place in Earth’s history prior to a major extinction event.

The fossilised Glossopteris, as an example, became extinct at the end of the Permian Period. The “Great Dying”, was a mass extinction event that is thought to have been driven by greenhouse gas-induced climate change.

Understanding this extinction event could help scientists better predict the impact of the world’s current unsustainable carbon emissions and latest climate crisis, says Prevec.

But, as it stands, in South Africa very little research is being conducted in the area of paleobotany. There needs to be a greater understanding of past ecosystems as a whole to understand the ecosystem collapse seen during extinction events, but that has been missing from research, explains Prevec.

“Historically, our focus has always been vertebrates… most people are drawn to things with teeth.”

Lonely field

Prevec is one of just three paleobotanists in the country and the only one working with macro plants instead of microscopic plant structures.

“I am pretty much the only one looking at leaves in South Africa, which is a crime,” says Prevec. “For one person to look at all the leaves on the botanical record, for the whole of time, right across the country, is just crazy.”

“It’s lifetimes of work,” says Prevec. But, “if you don’t know what the ecosystems are doing before the extinction event, how do you evaluate what actually changes during that event?”

As climate change has steadily become a more pressing matter on the agenda, people have become more aware of ecosystems and how ecosystems change, says Prevec.

As a result, “more people are recognising the need to know what happened in the past; what happened with an extinction event that looks very similar to what we face now, and how that can tell us about what is happening today”. DM/OBP

Seed cones of the Glossopteris plant preserved with its pollen cones, solve a 200-year-old botanical mystery as to the reproduction of the long-extinct plant which formed most of the economically important coal reserves used today, says Dr Rose Prevec. (Photo: Rose Prevec)

By Jamie Venter | 6 Dec 2022

The discovery of exquisitely preserved plant and insect fossils may shed light on previously unknown life of the past. But these tiny fossils may have an even bigger story to tell: the story of a mass extinction believed to have been driven by greenhouse gas emissions that draw an eerie parallel to today’s climate crisis.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Sutherland is well known for its great expanse of fossil fields, which are littered with the bones of dinosaurs that once roamed the landscape. It is also known for being cold — really cold. This reputation is well-earned, but the large reptilian remains of life before humans make the Karoo’s bitter cold worthwhile for tourists and palaeontologists alike.

Just a short way out of town, on a small site no larger than six by five metres, thousands of remarkably well-preserved fossilised plants, birds and insects may hold the key to understanding extinction events of the past and assist scientists in predicting the effects of the current climate crisis. This is according to new research conducted by paleobotanist Dr Rose Prevec.

“Sutherland is known for its vertebrate fossils; the bones preserve really well in that area,” said Prevec. But despite attempts to locate evidence of fossilised plant life in the area, there have been very few well-preserved discoveries. This is because the soft tissues that predominantly make up plants and insects tend not to fossilise at all, except under very unique circumstances.

‘Miraculous’ find

“It was really miraculous to find any plants, let alone something so beautifully preserved,” said Prevec.

The site — which was originally discovered in 2009, but on which excavations only began in 2016 due to a lack of interest in funding the dig — has unearthed thousands of plant and insect fossils, some of which are new to science.

This 40-million-year-old fossilised leech found in the Karoo could be the oldest freshwater leech discovered, says paleobotanist Dr Rose Prevec. (Photo: Rose Prevec)

The fossils unearthed reveal life that existed in a lakeshore ecosystem, 266 million years ago, states the research paper.

Some of the discoveries include a fossilised leech, mosses, liverworts, winged insects, mites and leaves of plants such as Glossopteris, which formed most of the economically important coal reserves used today.

The leech may be the oldest freshwater leech in the world and is dated as far back as 40 million years, explains Prevec.

Although the fossils may be small, they are compelling.

When the researchers found the first mite, they believed it to be a seed, explains Prevec. But, “we looked closer and these legs appeared and it was this giant tick-looking thing. And then there was a lot of excited shrieking,” says Prevec.

“These fossils are important because they fill in a gap in the fossil record,” says Prevec.

Currently, scientists have a good idea of the vertebrate animals that existed because they preserve so well and are found in abundance, but there is very little understanding of the plant and insect life from the same ecosystems.

The discoveries of these fossils will help fill in the gaps in scientists’ understanding of evolution of these insects and plants, explains Prevec.

This is an important gap to fill, because, as well as contributing to scientists’ understanding of evolution, it also has implications for current climate change research.

To understand an “ecosystem, measure biodiversity and how it changed with shifting climates, we need to look at the small things and the green things”, says Prevec.

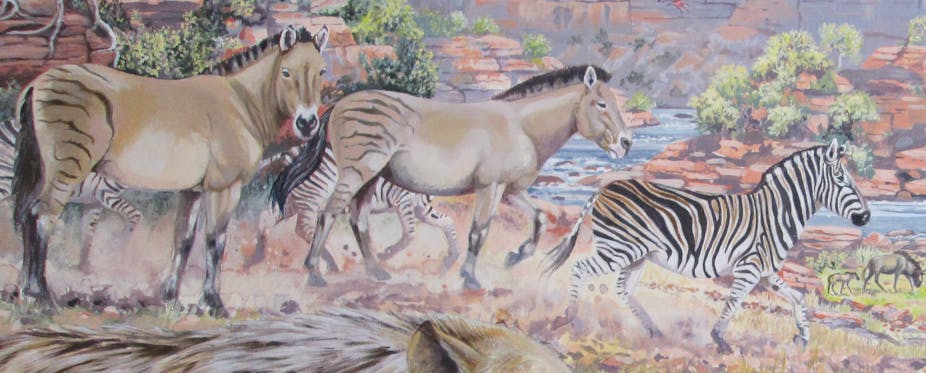

“If you were to study a modern ecosystem and wanted to understand climate change, you wouldn’t look at six antelope and a lion,” says Prevec.

“It’s really the plants, the insects, the small things, the things that are at the base of the food chain, that really tell you what’s going on with an ecosystem.”

Thousands of remarkably well preserved fossilised plants, birds and insects were discovered in the Karoo, some of which showed intact wings, hairs and even coloration. Such well preserved invertebrate fossils, as pictured above, are extremely rare to find, says paleobotanist, Dr Rose Prevec. (Photo: Rose Prevec)

Understanding this ecosystem and the fossils it left behind is particularly important because of their place in Earth’s history prior to a major extinction event.

The fossilised Glossopteris, as an example, became extinct at the end of the Permian Period. The “Great Dying”, was a mass extinction event that is thought to have been driven by greenhouse gas-induced climate change.

Understanding this extinction event could help scientists better predict the impact of the world’s current unsustainable carbon emissions and latest climate crisis, says Prevec.

But, as it stands, in South Africa very little research is being conducted in the area of paleobotany. There needs to be a greater understanding of past ecosystems as a whole to understand the ecosystem collapse seen during extinction events, but that has been missing from research, explains Prevec.

“Historically, our focus has always been vertebrates… most people are drawn to things with teeth.”

Lonely field

Prevec is one of just three paleobotanists in the country and the only one working with macro plants instead of microscopic plant structures.

“I am pretty much the only one looking at leaves in South Africa, which is a crime,” says Prevec. “For one person to look at all the leaves on the botanical record, for the whole of time, right across the country, is just crazy.”

“It’s lifetimes of work,” says Prevec. But, “if you don’t know what the ecosystems are doing before the extinction event, how do you evaluate what actually changes during that event?”

As climate change has steadily become a more pressing matter on the agenda, people have become more aware of ecosystems and how ecosystems change, says Prevec.

As a result, “more people are recognising the need to know what happened in the past; what happened with an extinction event that looks very similar to what we face now, and how that can tell us about what is happening today”. DM/OBP