BUSINESS REFLECTION

Southern Africa’s secret to elephant conservation success — it’s the economy, stupid

Rescue elephants are led to a reserve waterhole for bathing and drinking at a an orphanage outside Hoedspruit, Limpopo. (Photo: Tiara Walters)

By Ed Stoddard |14 Nov 2024

Rescue elephants are led to a reserve waterhole for bathing and drinking at a an orphanage outside Hoedspruit, Limpopo. (Photo: Tiara Walters)

By Ed Stoddard |14 Nov 2024

Southern Africa is bucking the trend on the continent in terms of the decline in elephant populations, according to studies. And the reasons have a lot to do with economics.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A study published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy Sciences has confirmed two widely known facts regarding African elephants but provided fresh data to flesh out the big picture.

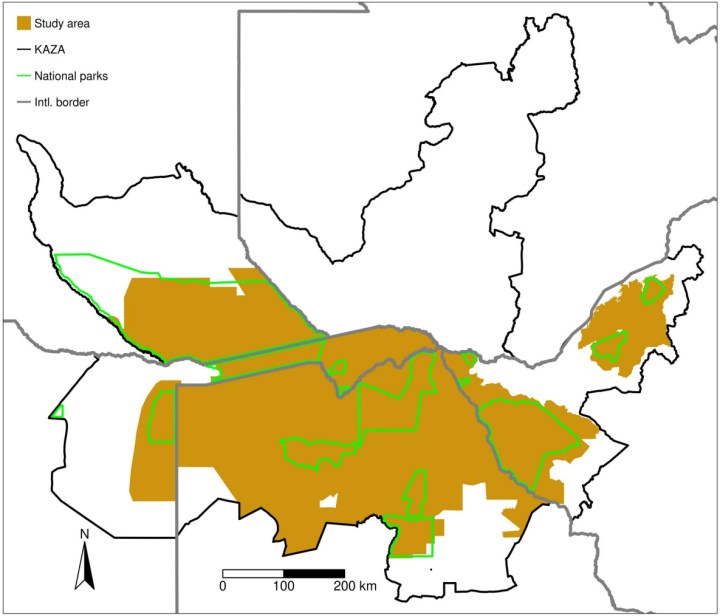

The peer-reviewed paper – Survey-based inference of continental African elephant decline – examined hundreds of population surveys of forest and savanna elephants from 475 sites across 37 African countries between 1964 and 2016.

“Both species have experienced substantial declines at the majority of survey sites. Forest elephant sites have declined on average by 90%, whereas savanna elephant sites have declined by 70% over the study period,” the study says.

But the study notes that there are mammoth-sized regional variations, with southern Africa notably bucking the trend.

“For the south, 42% of sites demonstrated a density increase over the modelled period. In contrast, only 10% of east sites are estimated to have increased, and none in the north,” it says.

Both trends are well known in conservation circles – in much of southern Africa, populations have been rising but, overall, in Africa, elephants are in precipitous decline for a range of reasons, including ivory poaching, habitat destruction, and fragmentation and conflict with humans.

This is the most exhaustive number-crunching on population surveys to date, providing plenty of food for thought for policymakers and conservationists.

“… a comprehensive evaluation of trend information from African elephant populations over the past half-century has been a critical outstanding scientific need necessary for informing debate around the species management and conservation. The results presented here fulfil this need,” the study says.

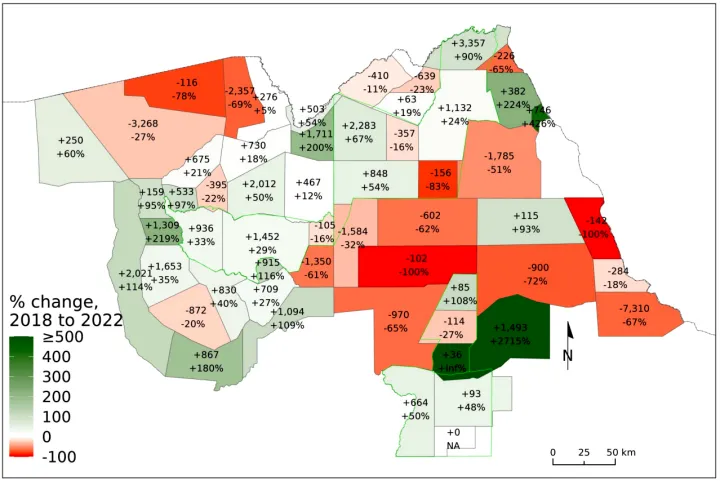

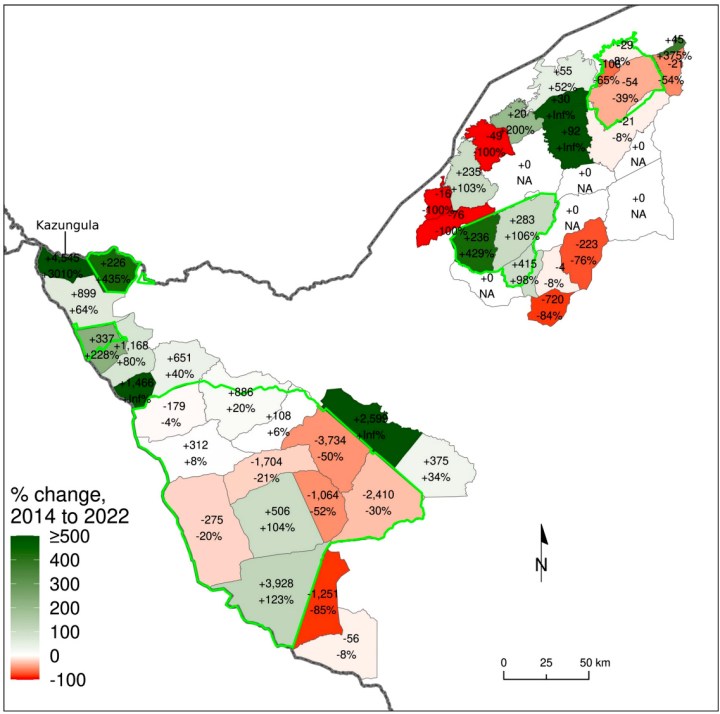

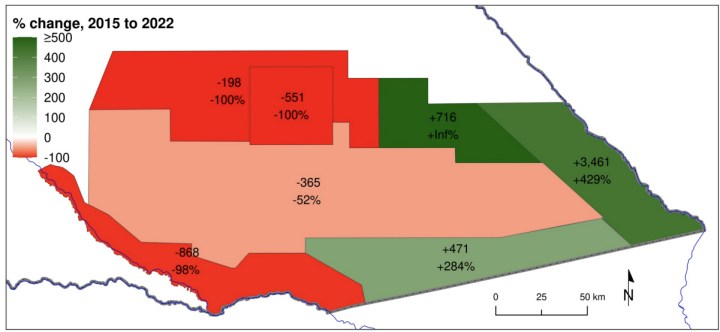

“These results indicated that conservation efforts are succeeding in some sites across regions of Africa. Such heterogeneity offers opportunities to identify key factors related to the efficacy of conservation efforts.”

The paper does not make policy recommendations, and most of the headlines about the study have been about the alarming decline in Africa’s elephant populations.

But the study does offer clues to what works and what doesn’t work for elephant conservation. And economics clearly plays a role.

Factors that have contributed to elephant conservation

One economic factor is costs. South Africa, for example, is the one significant elephant range state where the pachyderms are almost exclusively contained in fenced reserves. And those that are not, are meant to be fenced.

South Africa is also by far the most industrialised African economy, with the continent’s most capital-intensive commercial agricultural sector.

Fencing is the costly response of a relatively affluent and industrialised economy to potentially menacing megafauna and is a policy option that the ANC inherited in 1994 and has pointedly maintained.

Containment also minimises human-wildlife conflict, which is good for animals and people. But fences have mixed results as a deterrence to poaching, a point underscored by the rhino carnage in Kruger National Park.

One of the drawbacks to fencing is the potential ecological consequences of elephant populations swelling to a point where they eat themselves out of house and home – they need room to roam.

Another economic point to make is that South Africa allows private ownership of game. On the megafauna front, most of the country’s white rhino population is in private hands, largely because the owners have done a far better job protecting their herds than has been the case in state-run reserves. They have assets and that drives incentives to protect their property.

There are also elephants on private land in South Africa. But one of the ramifications of this conservation success story is that fewer private game ranchers want elephants because there are so many of the pachyderms in South Africa these days. So, South Africa’s elephant population could potentially be approaching a peak.

Ecotourism also plays a big role in the economics equation, both “non-consumptive” and “consumptive” – the former focuses on photographic wildlife excursions or simply watching animals, while the latter includes activities such as hunting.

With a couple of notable exceptions such as Kenya, southern Africa has by far the most developed “non-consumptive” ecotourism sector on the continent.

Botswana has Africa’s biggest population of elephants, with around 130,000. This state of affairs is partly explained by the fact that Botswana is sparsely populated by humans, who number around 2.5 million, and the pachyderms are mostly in remote areas with few people.

But Botswana also has a thriving non-consumptive ecotourism – or “safari” – sector that creates economic incentives to protect and maintain wildlife, including elephants. Tourism accounts, it seems, for about 13% of Botswana’s GDP.

Namibia, Zambia, South Africa and, to a lesser extent, Zimbabwe also have robust non-consumptive ecotourist offerings that bring in foreign currency, create jobs and business opportunities, and help ensure that prime elephant habitat is not turned into farmland or a mine or some such thing.

On the other hand

The flip side of the ecotourist sector is the elephant in the room – trophy hunting.

This makes animal welfare and rights activists, especially up north – you know, the countries that don’t have much in the way of dangerous megafauna – see red.

Opposition to hunting is perfectly legitimate; a lot of people simply do not like it for whatever reason.

But the problem is that it is often woefully misinformed and, in the case of Africa especially, fails to take into account the views of people who actually have to live in proximity to big animals that could kill their kith and kin or devour their crops.

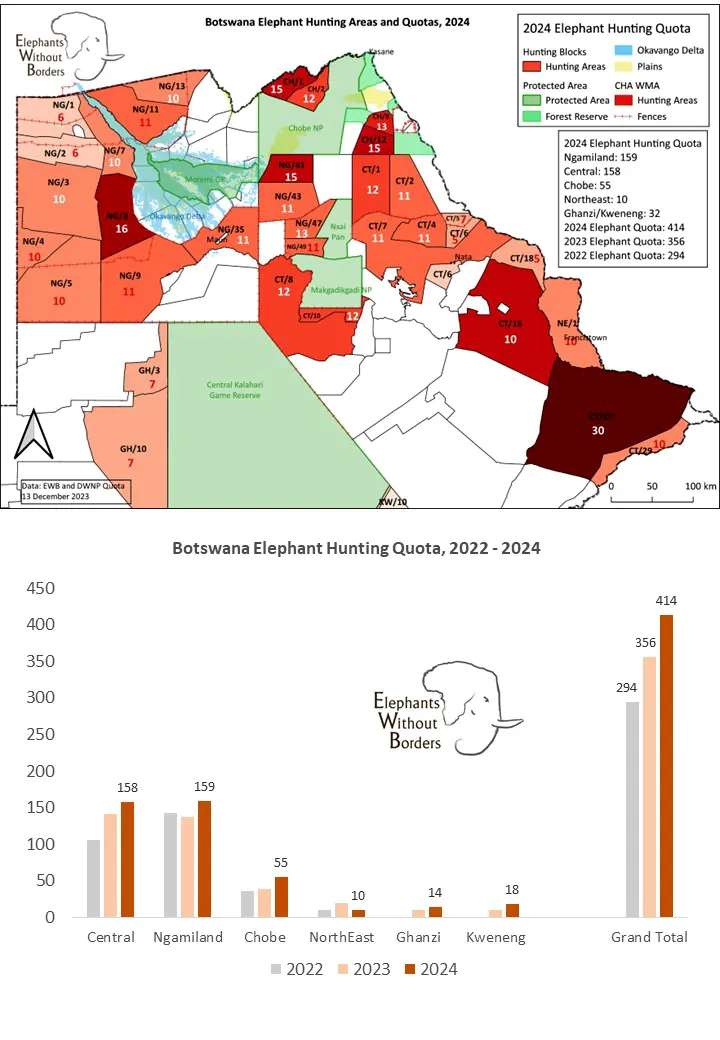

One cold hard fact of this matter is that outside of Cameroon in the west and Tanzania in the east, southern Africa is the one region on the continent that also has several elephant range states, where the animals can be legally hunted for sport: South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Mozambique.

And this is the region that has gone against the grain of elephant decline in Africa. To use a term from the dismal science, this is called an “economic indicator” and, in this case, it is one that can also be seen as an “ecological indicator”.

There is a lot of wrangling about how much money from hunting trickles down to the rural poor, but the same can be said about photographic tourism. And many areas where hunting takes place are unsuitable for photographic tourism because of the terrain, remoteness and lack of amenities.

As the authors of the study note, their research is aimed at informing debate on these issues.

On that score, a recent Oxford-led study found that campaigns such as those in the UK to ban the import of hunting trophies – and Africa is the main target – were counterproductive “[…] as hunting does, or could potentially, benefit 20 species and subspecies, and people”.

“Legal hunting for trophies is not a major threat to any of the species or subspecies imported to the UK, but likely or possibly represents a local threat to some populations of eight species,” the study found.

When it comes to elephant conservation, the phrase coined by James Carville, a strategist in Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 US presidential campaign, comes to mind. “It’s the economy, stupid.” DM