https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article ... algoa-bay/

MAVERICK CITIZEN: BIODIVERSITY

Shocking drop in number of African penguin numbers for Algoa Bay

By Estelle Ellis• 23 January 2020

The latest count at the biggest African penguin breeding colony on Earth, St Croix Island in Algoa Bay, has shown a 45% drop in breeding pairs in the past five years. Conservationists are saying that industrial over-fishing, pollution and an increase in shipping activity due to bunkering are all contributing to the biggest drop in African Penguin numbers seen since monitoring began in the 1980s.

There are only 13,000 breeding pairs of African penguins left in South Africa. The biggest breeding colony for these birds is at St Croix Island in Algoa Bay and Bird Island. The penguin population in Algoa Bay has fallen sharply, from 10,900 breeding pairs in 2015 to only 6,100 in 2019. Of the breeding pairs lost in Algoa Bay between 2018 and 2019, St. Croix Island accounted for 84% – with only 3,638 breeding pairs remaining on the island.

Environmental scientist, Ronelle Friend, has compiled a study showing the massive drop in breeding pairs of African penguins in Algoa Bay. The birds have two major breeding colonies in the bay at St. Croix Island and on Bird Island. Friend is also the co-founder of Algoa Bay Conservation, an organisation fighting to preserve biodiversity. She said the decrease did not occur “evenly” throughout the bay and added that this was the largest drop off in numbers in a single year since the 1980s when monitoring first started. Friend described this as “ecologically catastrophic”.

Friend explained that while a leading factor driving the penguins’ decline was food scarcity caused by industrialised fishing for sardines, she believed that it cannot alone account for the large decline in the number of breeding pairs.

“However, such a drastic demise over a short period of time, specifically the last year, indicates a more localised hazard that wrecked the habitat of specifically the St Croix Island penguins. This is evident as (in comparison) the contribution to the drop in numbers from Bird Island is very low. Bird Island is further away from the Port of Ngqura than St Croix Island.

“The only significant change that occurred in close proximity to St Croix Island, indeed less than 5km away, was the expansion of and pollution by Ship-to-Ship (STS) bunkering. During the last year, this ecologically dangerous refuelling operation in the anchorage areas of the Port of Coega has increased three-fold. The stress on the penguins in their foraging areas of more vessel movement in and out the anchorage area, more noise, more air pollution, more water pollution is definite,” Friend said.

Bunkering operations, allowing for ships to be refuelled at sea, commenced in Algoa Bay in 2016. In July 2019, more than 100 African penguins and other seabirds were oiled after a bunkering spill, of between 200 and 400 litres of oil, near the Port of Ngqura. The Liberian vessel Chrysanthi S was fined R350,000 following the spill.

Friend said it was becoming clear that the government’s plan to save the African penguin in Algoa Bay was not working.

“The penguin breeding pair numbers have decreased by 45% over the last five years. This indicates that the efforts and management plans that the department put in place did not work in Algoa Bay. Possibly the department did not accurately identify the threats to the penguins in Algoa Bay. In some areas, specifically in the Western Cape, penguin numbers have been more stable over the same time,” she added.

She said bunkering alone was, however, not responsible for the drop in numbers even though it was a major factor. “Penguins in Algoa Bay are also threatened by industrial overfishing of their food sources (mainly anchovies and sardines), and the pressure from polluted rivers (such as the contaminated Swartkops river). In addition, annual changes in the local fish abundance and a possible shift in the distribution of their food sources away from breeding colonies can also have a negative impact on penguin numbers. Also, the movement of vessels on the sea across their foraging areas and the associated noise and pollution (air and water pollution), can add pressure to the penguin population,” she added.

She said no environmental impact assessments were done before the commencement of bunkering services near St Croix Island. “The amount of fuel in the bunkering vessels on the surface of the sea is equivalent to the amount of fuel that 990 land-based fuel stations will issue in a month. If you want to set up one land-based fuel station, you need to do an EIA [Environmental Impact Assessment], but no EIA was required from the STS bunkering operators,” she added.

“We have lost 34% of the penguins at St Croix Island over the last year. In two years’ time, if the trend is continuing, we will have lost most of the breeding colony from St. Croix, currently the largest breeding colony of the African Penguin on Earth. The breeding colony of penguins at Bird Island is fortunately more stable and can sustain themselves for longer,” Friend explained.

Late last year, the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries issued a statement expressing “great concern” over the drop in African penguin numbers.

The department released its draft Biodiversity Management Plan for the African Penguin in October 2019.

The updated plan proposed new actions to conserve the species and halt the decline of the African Penguin in South Africa within its five-year timeframe and proposed plans to limit fishing around penguin colonies, and introduce zones for shipping and bunkering.

At the time, the plan came under fire by environmental and marine activists for not proposing that bunkering be halted in Algoa Bay altogether due to the close proximity of the St. Croix breeding colony. MC

Threats to African Penguins & Penguin Conservation

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5858

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65792

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Threats to African penguin population

Words, words, wordsLate last year, the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries issued a statement expressing “great concern” over the drop in African penguin numbers.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5858

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

Re: Threats to African penguin population

https://www.heraldlive.co.za/news/2020- ... -plummets/

African penguin population plummets

BY GUY ROGERS - 20 February 2020

GRAVE CONCERN: NMU penguin specialist Dr Lorien Pichegru

Image: FREDLIN ADRIAAN

The African penguin population in Algoa Bay has plummeted by at least 30% in the last four years — and that is bad news all round, penguin specialist researcher Dr Lorien Pichegru said yesterday.

The species is already officially classified as endangered, with its population having dropped 70% since 2004.

About half the remaining 15,000-odd breeding pairs across the bird’s global range, from Namibia to the western section of the Eastern Cape coast, occur in Algoa Bay, and St Croix Island is still home to the single biggest colony, she said.

“But while the numbers on Bird Island have remained stable, the numbers on St Croix are declining fast, from 7,500 to 4,500 breeding pairs — so 30-40% down in the past four years.”

The numbers, collated during annual census surveys undertaken in partnership with SANParks and the department of environment, forestry and fisheries, were quite clear and extremely worrying, she said.

“Even if you don’t love penguins, it should be a concern, because seabirds like penguins show us what is going on down below the surface of the ocean where we cannot easily see.

“What happens to the penguins is happening to the fish is happening to the fishermen and in the end will happen to all of us who rely on the oceans for food, tourism and a multitude of other reasons.”

There was likely a combination of reasons for the decline, she said.

“Some of the possible factors include that there is insufficient food which in turn could relate to climate change and fishing.

“Other possible factors include increased seismic survey activity and predation by seals who eat penguins when there are not enough fish.

“It could also be due an increase in shipping traffic in our bay related to offshore bunkering, as well as to the recent oil spills.

“It could also include an increased pollution load coming down our rivers.”

Pichegru said her assessment of the drop off in penguin numbers on St Croix correlated with an increase in the number of carcasses she had been finding during her beach surveys east of the Sundays River over the past six years.

African penguin population plummets

BY GUY ROGERS - 20 February 2020

GRAVE CONCERN: NMU penguin specialist Dr Lorien Pichegru

Image: FREDLIN ADRIAAN

The African penguin population in Algoa Bay has plummeted by at least 30% in the last four years — and that is bad news all round, penguin specialist researcher Dr Lorien Pichegru said yesterday.

The species is already officially classified as endangered, with its population having dropped 70% since 2004.

About half the remaining 15,000-odd breeding pairs across the bird’s global range, from Namibia to the western section of the Eastern Cape coast, occur in Algoa Bay, and St Croix Island is still home to the single biggest colony, she said.

“But while the numbers on Bird Island have remained stable, the numbers on St Croix are declining fast, from 7,500 to 4,500 breeding pairs — so 30-40% down in the past four years.”

The numbers, collated during annual census surveys undertaken in partnership with SANParks and the department of environment, forestry and fisheries, were quite clear and extremely worrying, she said.

“Even if you don’t love penguins, it should be a concern, because seabirds like penguins show us what is going on down below the surface of the ocean where we cannot easily see.

“What happens to the penguins is happening to the fish is happening to the fishermen and in the end will happen to all of us who rely on the oceans for food, tourism and a multitude of other reasons.”

There was likely a combination of reasons for the decline, she said.

“Some of the possible factors include that there is insufficient food which in turn could relate to climate change and fishing.

“Other possible factors include increased seismic survey activity and predation by seals who eat penguins when there are not enough fish.

“It could also be due an increase in shipping traffic in our bay related to offshore bunkering, as well as to the recent oil spills.

“It could also include an increased pollution load coming down our rivers.”

Pichegru said her assessment of the drop off in penguin numbers on St Croix correlated with an increase in the number of carcasses she had been finding during her beach surveys east of the Sundays River over the past six years.

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65792

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Threats to African penguin population

Parliament’s poached penguin eggs and the Great Guano War

By Don Pinnock• 2 July 2020

SIMONS TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA - JUNE 29: African penguins walk along the rocks at sunset on Boulders Beach June 29,2010 in Simon's Town, South Africa. The vulnerable species live in a penguin colony in False Bay that is part of Table Mountain National Park. Since breeding two pairs in 1982, the penguin colony has grown over the years to over 3,000. Tourists in country for the World Cup have brought double the usual numbers of people visiting the famous penguin breeding ground. (Photo by Paula Bronstein/Getty Images)

In penguin school the first lesson should be: never trust a human. But it’s a lesson fat, flightless birds seldom get the chance to learn – until it’s too late.

In June 2000, a bulk ore carrier named MV Treasure, owned by Good Faith Shipping, is holed by who knows what and sinks between Dassen and Robben islands off Cape Town.

On board are 1,344 tonnes of bunker oil, 56 tonnes of marine diesel and 64 tonnes of lube oil. Before long, hundreds of tonnes are in the sea and the shoreline looks a bit like the inside of a coal scuttle.

A few days later, the slick hits Robben then Dassen islands. Forget the irony of good faith and treasure: pray for the penguins.

This is old news, with resonances going back even further: Kapodistrias, Apollo Sea, bulk carriers which sank and spewed their black guts into the sea. Treasure, though, beats them all. It creates one of the world’s worst coastal bird disasters followed by the world’s most amazing sea-bird rescue operation. Thousands of officials, professionals, housewives and schoolchildren are joined by international film stars, boxers, models and oil-skinned workers, grabbing, shooing, boxing, scrubbing and feeding bemused penguins.

Some 19,000 unoiled birds are captured and transported to the safety of Cape Recife near Port Elizabeth, another 19,000 oiled birds are cleaned, tagged and, when the oil slick is dispersed, released.

This is 21st century conservation at its best. It gives me a warm glow to have been part of it – until I meet University of Cape Town avian researcher Phil Whittington. He tells me that until 1968 the South African Parliament had a breakfast special on penguin eggs. He mentions a Great Guano War and tells me that in the last 100 years the African penguin population has crashed by about 90%.

It’s all rather depressing and takes some of the lustre out of our rescue operation. But what catches my attention is the Guano War. Did grown men really kill each other over bird shit?

Well, it seems they did. From the information I dig out of some obscure books at the University of Cape Town and a handful of government reports, a strange tale begins to emerge.

It really starts with the Incas, who discover they can grow bumper crops using the smelly white stuff they scrape of nearby Peruvian islets. The tradition persists despite the decimation of Inca culture by the Spanish conquistadores. In 1835, some Peruvian guano is brought to Britain. It lands up in the hands of Alexander von Humboldt – after whom the Humboldt current will later be named.

He discovers it to be rich in nitrogen and phosphates and shows it to be an outstanding fertiliser for wheat and turnips. Soon, Liverpool merchants are daring the long passage to Peru and returning with holds full of “white gold”. Guano becomes the world’s first commercial fertiliser.

The African connection has to do with a rakish New York captain named Benjamin Morrell who has a penchant for wandering the oceans. In 1828, he sails up the coast from the Cape to Angola, hunting seals. He eventually writes a book with the windy title: A Narrative of Four Voyages to the South Sea, North and South Pacific Ocean, Ethiopic and Southern Atlantic Ocean, Indian and Antarctic Ocean from the Year 1822 to 1831.

An American critic calls Morrell “a great navigator, a successful sealer and merchant, a voluminous and entertaining writer and a romantic liar”. But in his book is a sentence which will sign the death warrant for millions of sea birds, including African penguins.

Commenting on a visit to lonely Ichaboe Island off the Namibian coast, he writes: “The surface of this island is covered with birds’ manure to a depth of 25 feet.”

Morrell is interested in seals, not guano, so he sails off. But his book falls into the hands of Liverpool businessman Andrew Livingstone, who charters three small sailing ships to hunt down Ichaboe. Two fail but the third, a brig named Ann under Captain Farr, hits pay dirt in March 1843.

The sea conditions are awful, Farr has no materials to construct a landing stage, each longboat of guano has to hammer through Ichaboe’s heavy surf and a southerly gale eventually parts the ship’s anchor chains. But he sails back to Britain with a goodly load of white gold and Livingstone makes a fortune.

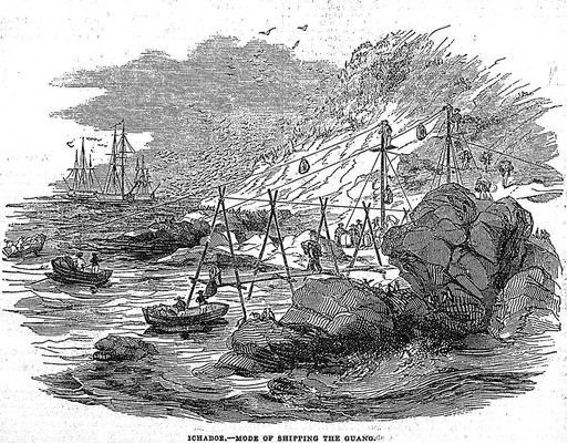

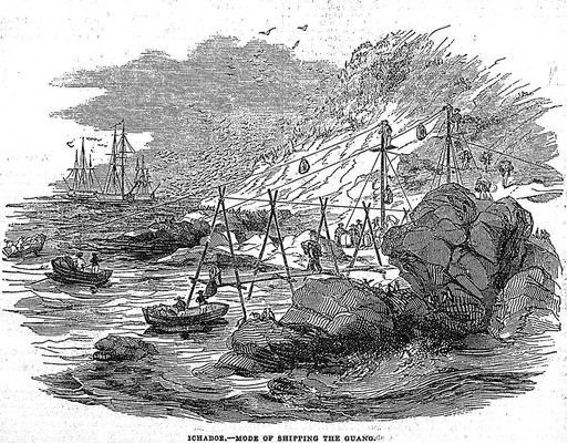

Ichaboe island Avian Demography Unit UCT (Image WikiCommons)

The businessman has a problem, though: nobody owns the island and he has to keep its whereabouts secret. He pays the ship’s crew to shut up and sends them away on other vessels. But a crafty steward has a piece of paper on which is written “26 South 14 East” which he sells to the highest bidder. The secret is out.

Before you can yell “hoist the mainsail” the next guano hunter is sailing southwards – then another, then another. The steward is obviously doing good, unprincipled business.

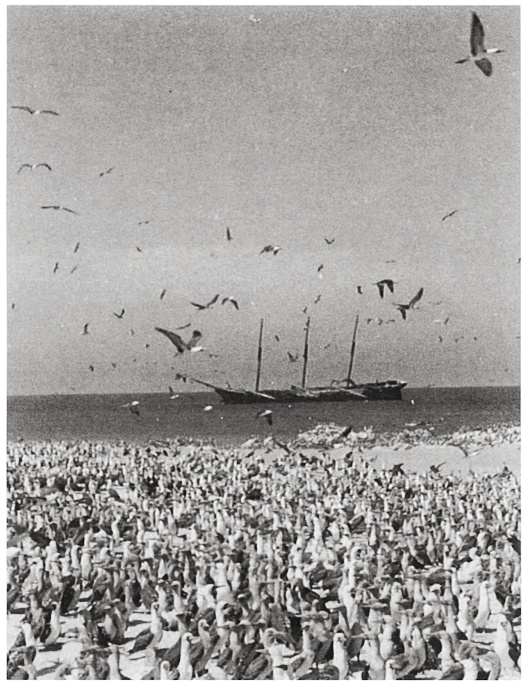

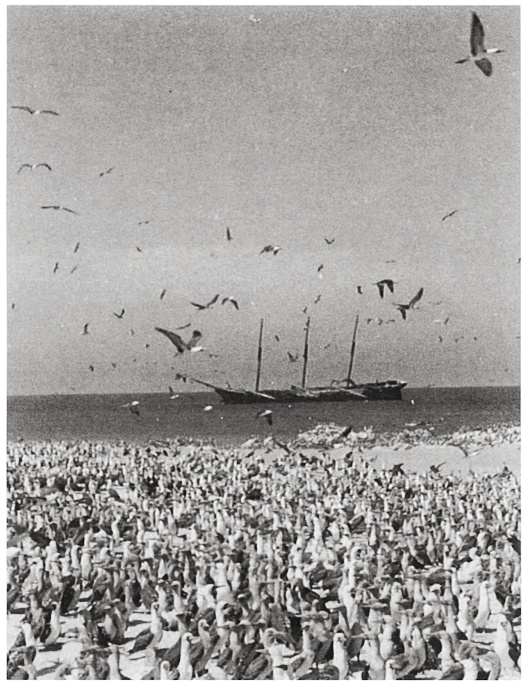

The first ship to arrive is the Douglas under Captain Wade. He leaves a record: “On first landing in November 1843 on the island which enjoyed for a time so odorous a celebrity, the place was literally alive with one mass of penguins and gannet. They were so tame that they would not move without compulsion. Thousands of eggs of the penguin, collected by the sailors, formed a savoury addition to their usual rations of salt meat.”

Guano diggers Ichaboe (Image WikiCommons)

Guano ship off Ichaboe Island (Image WikiCommons)

Captain Wade’s men hack away at the guano cliffs in blissful isolation, but not for long. Soon other ships appear over the horizon.

Before long Ichaboe is littered with spars, booms, topmasts, hawsers and sundry junk forming loading devices and crude shelters. So are the surrounding islands.

Within a month 20 ships are at anchor. Captain Wade takes possession of Ichaboe “in the name of Her Majesty, Queen Victoria”. By early 1844, the bobbing fleet of guano hunters has swelled to around 100. By this time hundreds of men are camping ashore under flapping canvas. Claims are staked. Tempers flare.

Then a black southeaster hammers the fleet, causing collisions and forcing vessels to run for open sea. When the gale dies down and the ships beat their way back to Ichaboe, it’s under new management. An Irish deserter from the Royal Navy named Ryan has convinced the temporarily marooned guano diggers to elect him president and has declared Ichaboe a republic. He demands £45 for use of the landing stage from each ship.

All hell breaks loose, aided by some smuggled liquor. No master or mate is allowed on the island; any officer attempting to land is pelted with dead penguins and threatened at knifepoint.

Then a well-provisioned intruder into Bedlam Britannia arrives, the American schooner Emmeline. Its master negotiates a deal with Ryan – provisions for guano – and its crew begins digging. The British are hopping mad. War is declared against the new republic.

Up to 2,000 men fight with picks and spades. The dead are hastily buried in the guano, unearthed by remorseless diggers and buried again in someone else’s claim.

Finally, a frigate, Thunderbolt, is called up from Cape Town and Ryan realises his little war is over. The marines land without opposition.

By January 1845, there are 6,000 men hacking away on the tiny island and 450 ships at anchor. No more incongruous sight has ever been beheld along that hostile, desert coast.

“It was a spectacle for the eye and mind,” remembered one Cape Town merchant, “which probably has never had a parallel in the history of commerce.”

By May 1845, it’s all over. About 300,000 tons of guano have been shipped to Britain at around £7 a ton and most of the penguin islands round the southern African coast have been scraped clean. Without guano in which to bury them, where are the corpses? There is no record of them.

What penguins remain have no burrows and they nest on the bare rock at the mercy of the elements and egg-eating kelp gulls. The islands are once again silent but for the cries of birds and the crashing of waves.

Dyer Island Then-and-now (Image WikiCommons)

The Cape government, bless it, then decides the islands need protection and in 1885 create the Division of Government Guano Islands. This regulates the mining of the non-existent guano and formalises the theft of penguin eggs.

Years later – in the 1940s – the writer Lawrence Green visits Ichaboe and finds only a tiny penguin colony there. He laments that “the dwindling of the penguins hits me in the stomach, for I know no finer breakfast than a penguin egg boiled for 20 minutes and served with butter, pepper and salt.”

This is a taste, it seems, shared by more people than is good for the beleaguered penguins. The tale is told in yellowing government records: state inspectors, it seems, are strangely obsessive in documenting the massive exercise in officially sanctioned looting.

A hundred years earlier it had been oil. A report in 1790 states that “the Government sends every year a detachment into the Isle of Roben (Robben Island) to shoot mors and manchots, which are called at the Cape, penguins, from which they extract great quantities of oil”.

Then comes guano, then eggs – and the authorities appear to have counted each egg. In the peak years at the turn of the last century the average annual penguin crop from Dassen Island alone exceeds 450,000 eggs. The total documented haul on the 24 islands where African penguins nested between 1900 and 1930 is a staggering 13 million eggs. All duly recorded.

Penguin egg collecting is halted in 1969, though the parliamentary kitchen carries on the traditional penguin breakfasts under special dispensation for some time after that. And, of course, poaching continues.

African penguins are the only members of the penguin family that breed in Africa and they predate human occupation by about 60 million years, appearing after the massive extinction of marine reptiles at the end of the Cretaceous period. They also pre-date seals, whales and dolphins. In the politics of life, they’re elder statesmen.

SIMON’S TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA – JUNE 29: African penguins walk along the rocks as a full moon rises at Boulders Beach June 29, 2010, in Simon’s Town, South Africa. The vulnerable species live in a penguin colony in False Bay that is part of Table Mountain National Park. Since breeding two pairs in 1982, the penguin colony has grown over the years to over 3,000. Tourists in the country for the World Cup have brought double the usual numbers of people visiting the famous penguin breeding ground. (Photo by Paula Bronstein/Getty Images)

Their nearest relatives are not puffins, which they resemble, but petrels and frigate birds. Penguins, however, exchanged air flight for water flight. Their Latin name, Spheniscus demersus, means “plunging wedge” and plunge they can, reaching 20km an hour and diving to 130m when necessary.

But their common name, penguin, is derived from a Portuguese word meaning “fat”, and the relationship between humans and fat flightless birds is not a good one. Ask the dodo.

So here’s a question I’m left with. Was the disaster caused by the sinking of the Treasure the latest event in a long history of disinterest in the plight of penguins, or did the magnificent public response mark a new environmental awareness which will characterise the 21st century?

The answer, either way, is of great importance to embattled African penguins. DM/ML

There’s an excellent but out-of-print book on the guano islands by Lawrence Green, At Daybreak for the Islands. It was printed by Howard Timmins in 1950 and should be available in libraries. A more recent book is The African Penguin, a Natural History by Phil Hockey and a must for penguin lovers (Struik, Cape Town).

By Don Pinnock• 2 July 2020

SIMONS TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA - JUNE 29: African penguins walk along the rocks at sunset on Boulders Beach June 29,2010 in Simon's Town, South Africa. The vulnerable species live in a penguin colony in False Bay that is part of Table Mountain National Park. Since breeding two pairs in 1982, the penguin colony has grown over the years to over 3,000. Tourists in country for the World Cup have brought double the usual numbers of people visiting the famous penguin breeding ground. (Photo by Paula Bronstein/Getty Images)

In penguin school the first lesson should be: never trust a human. But it’s a lesson fat, flightless birds seldom get the chance to learn – until it’s too late.

In June 2000, a bulk ore carrier named MV Treasure, owned by Good Faith Shipping, is holed by who knows what and sinks between Dassen and Robben islands off Cape Town.

On board are 1,344 tonnes of bunker oil, 56 tonnes of marine diesel and 64 tonnes of lube oil. Before long, hundreds of tonnes are in the sea and the shoreline looks a bit like the inside of a coal scuttle.

A few days later, the slick hits Robben then Dassen islands. Forget the irony of good faith and treasure: pray for the penguins.

This is old news, with resonances going back even further: Kapodistrias, Apollo Sea, bulk carriers which sank and spewed their black guts into the sea. Treasure, though, beats them all. It creates one of the world’s worst coastal bird disasters followed by the world’s most amazing sea-bird rescue operation. Thousands of officials, professionals, housewives and schoolchildren are joined by international film stars, boxers, models and oil-skinned workers, grabbing, shooing, boxing, scrubbing and feeding bemused penguins.

Some 19,000 unoiled birds are captured and transported to the safety of Cape Recife near Port Elizabeth, another 19,000 oiled birds are cleaned, tagged and, when the oil slick is dispersed, released.

This is 21st century conservation at its best. It gives me a warm glow to have been part of it – until I meet University of Cape Town avian researcher Phil Whittington. He tells me that until 1968 the South African Parliament had a breakfast special on penguin eggs. He mentions a Great Guano War and tells me that in the last 100 years the African penguin population has crashed by about 90%.

It’s all rather depressing and takes some of the lustre out of our rescue operation. But what catches my attention is the Guano War. Did grown men really kill each other over bird shit?

Well, it seems they did. From the information I dig out of some obscure books at the University of Cape Town and a handful of government reports, a strange tale begins to emerge.

It really starts with the Incas, who discover they can grow bumper crops using the smelly white stuff they scrape of nearby Peruvian islets. The tradition persists despite the decimation of Inca culture by the Spanish conquistadores. In 1835, some Peruvian guano is brought to Britain. It lands up in the hands of Alexander von Humboldt – after whom the Humboldt current will later be named.

He discovers it to be rich in nitrogen and phosphates and shows it to be an outstanding fertiliser for wheat and turnips. Soon, Liverpool merchants are daring the long passage to Peru and returning with holds full of “white gold”. Guano becomes the world’s first commercial fertiliser.

The African connection has to do with a rakish New York captain named Benjamin Morrell who has a penchant for wandering the oceans. In 1828, he sails up the coast from the Cape to Angola, hunting seals. He eventually writes a book with the windy title: A Narrative of Four Voyages to the South Sea, North and South Pacific Ocean, Ethiopic and Southern Atlantic Ocean, Indian and Antarctic Ocean from the Year 1822 to 1831.

An American critic calls Morrell “a great navigator, a successful sealer and merchant, a voluminous and entertaining writer and a romantic liar”. But in his book is a sentence which will sign the death warrant for millions of sea birds, including African penguins.

Commenting on a visit to lonely Ichaboe Island off the Namibian coast, he writes: “The surface of this island is covered with birds’ manure to a depth of 25 feet.”

Morrell is interested in seals, not guano, so he sails off. But his book falls into the hands of Liverpool businessman Andrew Livingstone, who charters three small sailing ships to hunt down Ichaboe. Two fail but the third, a brig named Ann under Captain Farr, hits pay dirt in March 1843.

The sea conditions are awful, Farr has no materials to construct a landing stage, each longboat of guano has to hammer through Ichaboe’s heavy surf and a southerly gale eventually parts the ship’s anchor chains. But he sails back to Britain with a goodly load of white gold and Livingstone makes a fortune.

Ichaboe island Avian Demography Unit UCT (Image WikiCommons)

The businessman has a problem, though: nobody owns the island and he has to keep its whereabouts secret. He pays the ship’s crew to shut up and sends them away on other vessels. But a crafty steward has a piece of paper on which is written “26 South 14 East” which he sells to the highest bidder. The secret is out.

Before you can yell “hoist the mainsail” the next guano hunter is sailing southwards – then another, then another. The steward is obviously doing good, unprincipled business.

The first ship to arrive is the Douglas under Captain Wade. He leaves a record: “On first landing in November 1843 on the island which enjoyed for a time so odorous a celebrity, the place was literally alive with one mass of penguins and gannet. They were so tame that they would not move without compulsion. Thousands of eggs of the penguin, collected by the sailors, formed a savoury addition to their usual rations of salt meat.”

Guano diggers Ichaboe (Image WikiCommons)

Guano ship off Ichaboe Island (Image WikiCommons)

Captain Wade’s men hack away at the guano cliffs in blissful isolation, but not for long. Soon other ships appear over the horizon.

Before long Ichaboe is littered with spars, booms, topmasts, hawsers and sundry junk forming loading devices and crude shelters. So are the surrounding islands.

Within a month 20 ships are at anchor. Captain Wade takes possession of Ichaboe “in the name of Her Majesty, Queen Victoria”. By early 1844, the bobbing fleet of guano hunters has swelled to around 100. By this time hundreds of men are camping ashore under flapping canvas. Claims are staked. Tempers flare.

Then a black southeaster hammers the fleet, causing collisions and forcing vessels to run for open sea. When the gale dies down and the ships beat their way back to Ichaboe, it’s under new management. An Irish deserter from the Royal Navy named Ryan has convinced the temporarily marooned guano diggers to elect him president and has declared Ichaboe a republic. He demands £45 for use of the landing stage from each ship.

All hell breaks loose, aided by some smuggled liquor. No master or mate is allowed on the island; any officer attempting to land is pelted with dead penguins and threatened at knifepoint.

Then a well-provisioned intruder into Bedlam Britannia arrives, the American schooner Emmeline. Its master negotiates a deal with Ryan – provisions for guano – and its crew begins digging. The British are hopping mad. War is declared against the new republic.

Up to 2,000 men fight with picks and spades. The dead are hastily buried in the guano, unearthed by remorseless diggers and buried again in someone else’s claim.

Finally, a frigate, Thunderbolt, is called up from Cape Town and Ryan realises his little war is over. The marines land without opposition.

By January 1845, there are 6,000 men hacking away on the tiny island and 450 ships at anchor. No more incongruous sight has ever been beheld along that hostile, desert coast.

“It was a spectacle for the eye and mind,” remembered one Cape Town merchant, “which probably has never had a parallel in the history of commerce.”

By May 1845, it’s all over. About 300,000 tons of guano have been shipped to Britain at around £7 a ton and most of the penguin islands round the southern African coast have been scraped clean. Without guano in which to bury them, where are the corpses? There is no record of them.

What penguins remain have no burrows and they nest on the bare rock at the mercy of the elements and egg-eating kelp gulls. The islands are once again silent but for the cries of birds and the crashing of waves.

Dyer Island Then-and-now (Image WikiCommons)

The Cape government, bless it, then decides the islands need protection and in 1885 create the Division of Government Guano Islands. This regulates the mining of the non-existent guano and formalises the theft of penguin eggs.

Years later – in the 1940s – the writer Lawrence Green visits Ichaboe and finds only a tiny penguin colony there. He laments that “the dwindling of the penguins hits me in the stomach, for I know no finer breakfast than a penguin egg boiled for 20 minutes and served with butter, pepper and salt.”

This is a taste, it seems, shared by more people than is good for the beleaguered penguins. The tale is told in yellowing government records: state inspectors, it seems, are strangely obsessive in documenting the massive exercise in officially sanctioned looting.

A hundred years earlier it had been oil. A report in 1790 states that “the Government sends every year a detachment into the Isle of Roben (Robben Island) to shoot mors and manchots, which are called at the Cape, penguins, from which they extract great quantities of oil”.

Then comes guano, then eggs – and the authorities appear to have counted each egg. In the peak years at the turn of the last century the average annual penguin crop from Dassen Island alone exceeds 450,000 eggs. The total documented haul on the 24 islands where African penguins nested between 1900 and 1930 is a staggering 13 million eggs. All duly recorded.

Penguin egg collecting is halted in 1969, though the parliamentary kitchen carries on the traditional penguin breakfasts under special dispensation for some time after that. And, of course, poaching continues.

African penguins are the only members of the penguin family that breed in Africa and they predate human occupation by about 60 million years, appearing after the massive extinction of marine reptiles at the end of the Cretaceous period. They also pre-date seals, whales and dolphins. In the politics of life, they’re elder statesmen.

SIMON’S TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA – JUNE 29: African penguins walk along the rocks as a full moon rises at Boulders Beach June 29, 2010, in Simon’s Town, South Africa. The vulnerable species live in a penguin colony in False Bay that is part of Table Mountain National Park. Since breeding two pairs in 1982, the penguin colony has grown over the years to over 3,000. Tourists in the country for the World Cup have brought double the usual numbers of people visiting the famous penguin breeding ground. (Photo by Paula Bronstein/Getty Images)

Their nearest relatives are not puffins, which they resemble, but petrels and frigate birds. Penguins, however, exchanged air flight for water flight. Their Latin name, Spheniscus demersus, means “plunging wedge” and plunge they can, reaching 20km an hour and diving to 130m when necessary.

But their common name, penguin, is derived from a Portuguese word meaning “fat”, and the relationship between humans and fat flightless birds is not a good one. Ask the dodo.

So here’s a question I’m left with. Was the disaster caused by the sinking of the Treasure the latest event in a long history of disinterest in the plight of penguins, or did the magnificent public response mark a new environmental awareness which will characterise the 21st century?

The answer, either way, is of great importance to embattled African penguins. DM/ML

There’s an excellent but out-of-print book on the guano islands by Lawrence Green, At Daybreak for the Islands. It was printed by Howard Timmins in 1950 and should be available in libraries. A more recent book is The African Penguin, a Natural History by Phil Hockey and a must for penguin lovers (Struik, Cape Town).

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65792

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Threats to African Penguins & Penguin Conservation

African penguins are heading towards extinction – here’s how we can save them

By Lewis Pugh• 1 December 2020

African penguins walk on rocks on Boulders beach in Simon’s Town. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Nic Bothma)

The science is clear: the African penguin is likely to be functionally extinct on the west coast in less than 15 years, unless we take immediate action.

There’s a magical moment of transition when a penguin crosses from land to water. Earth-bound, they are slow and cumbersome; as soon as they enter the ocean, they become sleek and agile, diving with torpedo precision to forage for life-sustaining fish. That is, assuming there are fish to be had.

Last week I drove out to Stony Point near Hermanus to assist the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds (Sanccob) with a release of rehabilitated African penguins. As I opened one box and watched its eager occupant waddle towards the water, fat and glossy with good health, I was struck by the difference between him and some of the resident birds.

I heard the despair in Sanccob marine scientist Lauren Waller’s voice as she pointed out birds that likely wouldn’t make it through the next few days. I’ve visited penguin colonies all over the southern hemisphere, but until now, I’ve never seen a starving penguin. It was eerily reminiscent of the malnourished polar bears I’ve seen in the north.

Competing for food

Many of these wild penguins were moulting – something penguins do every year. The birds stay ashore for up to 21 days to shed and regrow their protective feathers. Because they can’t swim during their moult, they need to eat plenty before they come ashore to make it through their fast. These birds should have been at their fattest, but a good number of them were seriously emaciated, their breastbones pointing through their feathers when they fanned their wings.

The resources in our oceans are not endless, and they are no longer abundant, thanks to the combined threats of global warming, pollution and industrial overfishing. Standing on that rocky shoreline it became clear to me how acutely the African penguin is feeling these changes.

Some of these birds may have swum hundreds of kilometres to find food. Marine researchers from BirdLife South Africa recently discovered premoulting penguins from Dassen Island turning up in De Hoop nature reserve some 350km away. Swimming such a long distance around Cape Point is not the best strategy when you’re trying to put on weight, but these birds have no choice.

Functionally extinct

The science is clear: the African penguin is likely to be functionally extinct on the west coast in less than 15 years, unless we take immediate action. Functionally extinct means that a population has declined to the point where it is no longer viable and can no longer produce a new generation.

When surveys began in the early 1900s there were three million African penguins. Since then we have lost 95% of the population, and their numbers continue to drop. In 2000, there were an estimated 53,000. Today, there are just 17,700 breeding pairs.

They are now more vulnerable than the white rhino, the polar bear or the giant panda.

Oil on water

If the situation wasn’t dire enough on the west coast, a new threat has emerged on the east coast, with offshore fuel ship-to-ship bunkering in Algoa Bay, close to the largest remaining African penguin colony at St Croix Island. The inherently risky operation of transferring fuel from one vessel to another at sea has already resulted in two oil spills.

Action plan

We are now at the point where every bird counts. Conservation agencies are doing everything they can to protect this iconic species.

Three crucial actions from our government could make all the difference to the African penguin’s survival:

- Creating a No-Take Fishing Zone of at least a 20km radius around penguin colonies and their foraging grounds, so that the penguins are not competing with fishing companies.

- Shifting offshore bunkering away from penguin colonies. Why take the risk? Why allow ships to transfer oil from one vessel to another in such close proximity to South Africa’s biggest African penguin colony in Algoa Bay?

- As long as ships carry oil, there are likely to be oil spills. This is especially the case off South Africa’s coast, which is a major sea route and has some of the roughest seas in the world. Therefore, we must ensure that all vessels transiting around South Africa are required by law to have a wildlife response plan to mitigate the impact of oil on marine wildlife in the event of a spill.

Sea blind

It’s a little known fact that South Africa is actually more sea than land. Our exclusive economic zone (EEZ) stretches 200 nautical miles from our shores. That gives us 1.5 million km2 of ocean, compared with 1.2 million km2 of land – and yet we fail to recognise or properly protect our ocean resources. It is as if we are sea blind.

Our coast is a prime tourist destination. Visitors come from all over the world to see our magnificent beaches, whales, penguins and sharks, providing a crucial boost to our economy. Yet South Africa has designated less than 15% of its coastline as a protected area – less than half the international recommendation. And less than 1% is classified as “fully protected”.

Repeating history

Hermanus in springtime is idyllic. With the fynbos in bloom, the flowers seem to flow down the slopes of the Hottentots Holland range to meet the sea. It’s easy to see why tourists love to come here, particularly during the whale-watching season, when the Southern Rights come in close to shore with their calves to breach and tail lob. But we should not forget that this was once the site of an ecocide, when humpback whales and Southern Rights were hunted to the brink of extinction.

We pulled back just in time; whaling was banned and whale numbers are recovering. Now the local economy relies almost entirely on its natural wildlife. And yet we seem intent on repeating our folly. We may not be actively hunting the penguin, but by failing to put protective measures in place, we are sealing their fate through inaction.

Fighting chance

Hopelessness and despondency are one of the greatest threats to our wildlife – another reason we simply cannot afford to lose the African penguin.

This year has been dominated by Covid-19 and the economic crisis. But we must not let this distract us from protecting the environment on which we all depend.

The three measures outlined here are not unreasonable. Each one is easily doable; together they can change the future of the African penguin. What we are asking for is the protection of less than 0.5% of South Africa’s waters.

Sadly, we will not be able to save every bird. But we can still give this beloved South African species a fighting chance. I urge the government to take action today.

By Lewis Pugh• 1 December 2020

African penguins walk on rocks on Boulders beach in Simon’s Town. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Nic Bothma)

The science is clear: the African penguin is likely to be functionally extinct on the west coast in less than 15 years, unless we take immediate action.

There’s a magical moment of transition when a penguin crosses from land to water. Earth-bound, they are slow and cumbersome; as soon as they enter the ocean, they become sleek and agile, diving with torpedo precision to forage for life-sustaining fish. That is, assuming there are fish to be had.

Last week I drove out to Stony Point near Hermanus to assist the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds (Sanccob) with a release of rehabilitated African penguins. As I opened one box and watched its eager occupant waddle towards the water, fat and glossy with good health, I was struck by the difference between him and some of the resident birds.

I heard the despair in Sanccob marine scientist Lauren Waller’s voice as she pointed out birds that likely wouldn’t make it through the next few days. I’ve visited penguin colonies all over the southern hemisphere, but until now, I’ve never seen a starving penguin. It was eerily reminiscent of the malnourished polar bears I’ve seen in the north.

Competing for food

Many of these wild penguins were moulting – something penguins do every year. The birds stay ashore for up to 21 days to shed and regrow their protective feathers. Because they can’t swim during their moult, they need to eat plenty before they come ashore to make it through their fast. These birds should have been at their fattest, but a good number of them were seriously emaciated, their breastbones pointing through their feathers when they fanned their wings.

The resources in our oceans are not endless, and they are no longer abundant, thanks to the combined threats of global warming, pollution and industrial overfishing. Standing on that rocky shoreline it became clear to me how acutely the African penguin is feeling these changes.

Some of these birds may have swum hundreds of kilometres to find food. Marine researchers from BirdLife South Africa recently discovered premoulting penguins from Dassen Island turning up in De Hoop nature reserve some 350km away. Swimming such a long distance around Cape Point is not the best strategy when you’re trying to put on weight, but these birds have no choice.

Functionally extinct

The science is clear: the African penguin is likely to be functionally extinct on the west coast in less than 15 years, unless we take immediate action. Functionally extinct means that a population has declined to the point where it is no longer viable and can no longer produce a new generation.

When surveys began in the early 1900s there were three million African penguins. Since then we have lost 95% of the population, and their numbers continue to drop. In 2000, there were an estimated 53,000. Today, there are just 17,700 breeding pairs.

They are now more vulnerable than the white rhino, the polar bear or the giant panda.

Oil on water

If the situation wasn’t dire enough on the west coast, a new threat has emerged on the east coast, with offshore fuel ship-to-ship bunkering in Algoa Bay, close to the largest remaining African penguin colony at St Croix Island. The inherently risky operation of transferring fuel from one vessel to another at sea has already resulted in two oil spills.

Action plan

We are now at the point where every bird counts. Conservation agencies are doing everything they can to protect this iconic species.

Three crucial actions from our government could make all the difference to the African penguin’s survival:

- Creating a No-Take Fishing Zone of at least a 20km radius around penguin colonies and their foraging grounds, so that the penguins are not competing with fishing companies.

- Shifting offshore bunkering away from penguin colonies. Why take the risk? Why allow ships to transfer oil from one vessel to another in such close proximity to South Africa’s biggest African penguin colony in Algoa Bay?

- As long as ships carry oil, there are likely to be oil spills. This is especially the case off South Africa’s coast, which is a major sea route and has some of the roughest seas in the world. Therefore, we must ensure that all vessels transiting around South Africa are required by law to have a wildlife response plan to mitigate the impact of oil on marine wildlife in the event of a spill.

Sea blind

It’s a little known fact that South Africa is actually more sea than land. Our exclusive economic zone (EEZ) stretches 200 nautical miles from our shores. That gives us 1.5 million km2 of ocean, compared with 1.2 million km2 of land – and yet we fail to recognise or properly protect our ocean resources. It is as if we are sea blind.

Our coast is a prime tourist destination. Visitors come from all over the world to see our magnificent beaches, whales, penguins and sharks, providing a crucial boost to our economy. Yet South Africa has designated less than 15% of its coastline as a protected area – less than half the international recommendation. And less than 1% is classified as “fully protected”.

Repeating history

Hermanus in springtime is idyllic. With the fynbos in bloom, the flowers seem to flow down the slopes of the Hottentots Holland range to meet the sea. It’s easy to see why tourists love to come here, particularly during the whale-watching season, when the Southern Rights come in close to shore with their calves to breach and tail lob. But we should not forget that this was once the site of an ecocide, when humpback whales and Southern Rights were hunted to the brink of extinction.

We pulled back just in time; whaling was banned and whale numbers are recovering. Now the local economy relies almost entirely on its natural wildlife. And yet we seem intent on repeating our folly. We may not be actively hunting the penguin, but by failing to put protective measures in place, we are sealing their fate through inaction.

Fighting chance

Hopelessness and despondency are one of the greatest threats to our wildlife – another reason we simply cannot afford to lose the African penguin.

This year has been dominated by Covid-19 and the economic crisis. But we must not let this distract us from protecting the environment on which we all depend.

The three measures outlined here are not unreasonable. Each one is easily doable; together they can change the future of the African penguin. What we are asking for is the protection of less than 0.5% of South Africa’s waters.

Sadly, we will not be able to save every bird. But we can still give this beloved South African species a fighting chance. I urge the government to take action today.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75255

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Threats to African Penguins & Penguin Conservation

Media Release: Boulders African Penguin Colony Have New Nesting Homes

09 February 2021

Boulders Penguin Colony within the Table Mountain National Park (TMNP) has recently embarked on a new nest development project together with conservation partners where rangers have removed and replaced 58 artificial nest boxes, to improve breeding conditions for the African penguin species.

These new Nesting hides are essential for colonies that are greatly exposed to predation and various environmental factors. Replacing lost habitat with artificial nesting structures is considered to be a useful conservation intervention given the decline of the species.

The nest boxes were first introduced to Boulders in 2003, where 62 of the formacrete nest boxes were installed. The concern regarding this prototype was the size of the formacrete nest box, therefore, it was concluded that this prototype offered less protection. There have been a number of iterations over the years with continual adaptions based on efficacy and on-site monitoring.

"The nest boxes provide safety from predators and limits exposure to adverse weather conditions such as extreme heat and heavy rain leading to floods. The overall population of the African penguin is declining and various interventions are in place to assist with increasing their numbers. It is believed that providing artificial nests will assist in breeding success of the African Penguin and therefore assist in increasing the overall population of the African penguin," says Alison Kock, Cape Research Centre Marine Biologist.

After much consideration, the latest design that has been developed is one that is made of a geotextile fabric that is both non-toxic and environmentally friendly. This prototype is based on measurements of naturally dug burrows made of guano. 50 of these latest nest boxes were installed at Boulders at the end of January 2021.

This project is ongoing and will be monitored carefully to determine the efficacy of design and nesting success. The outcomes of this monitoring will be assessed and potentially incorporated into new designs.

Issued by:

South African National Parks (SANParks) Corporate Communications

Media enquiries:

Reynold "Rey" Thakhuli

SANParks Acting Head of Communications

073 373 4999

Email: rey.thakhuli@sanparks.org

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65792

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Threats to African Penguins & Penguin Conservation

I would also like to have a house there

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65792

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Threats to African Penguins & Penguin Conservation

Penguins can’t get enough to eat

BY SHEREE BEGA - 23RD MAY 2021 - THE MAIL AND GUARDIAN

When one of South Africa’s worst environmental disasters unfolded 21 years ago, Lauren Waller made her way to the Salt River warehouse in Cape Town, donned rubber gloves and volunteered to help rehabilitate 19 000 oil-soaked African penguins.

It was June 2000 and the MV Treasure, a bulk iron ore carrier, had sunk between two key breeding islands for African penguins, Robben Island in Table Bay and Dassen Island near Cape Town, spilling 400 tonnes of bunker oil into the sea.

Now there is a new alarm bell ringing. Endangered African penguins are being pushed to the brink of extinction by food scarcity, oil spills, extreme weather, predation, sub-optimal breeding habitats and disease, according to scientists and various organisations.

The charismatic seabirds, which are slow to breed and long-lived, are “gasping for air”, says Waller, the Leiden conservation fellow for the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds (Sanccob). “There’re less birds in the wild today than were affected by the Treasure.” Around 40 000 were affected by the oil spill.

In the early 1900s, there were three million African penguins inhabiting the islands off the coast of Southern Africa. By 2019, South Africa’s population had dwindled to 13 600 breeding pairs.

Alistair McInnes, the seabird conservation programme manager at BirdLife South Africa, says: “The smaller the population gets the more difficult it is to recover.”

The main reason for their rapid decline is the limited availability of their food, say the scientists. Recent shifts in the distribution of sardines and anchovies, key to the marine food web, have caused a mismatch between penguin breeding, when they need more food to feed their chicks, and fish stocks, according to BirdLife International.

Commercial fishing by the small pelagic purse seine fishing sector — when a large net is towed and drawn closed — has left the penguins in competition for food, especially during the breeding season

Penguins forage 20km to a maximum of 40km from their breeding site; foraging further causes unsustainably high-energy expenditure. This means they are unable to feed their chicks regularly.

In 2008, to counter fishing pressure, the department of environmental affairs began a pioneering island closure experiment, alternatively opening and closing four of the largest African penguin breeding colonies — Dassen and Robben islands, St Croix Island, near Gqeberha in Algoa Bay and Bird Island off the shore of Lambert’s Bay — to the pelagic fishing sector for a radius of 20km.

Research led by ecologist Richard Sherley, of the University of Exeter and the University of Cape Town, showed how these small no-fishing zones improved the survival of chicks at Dassen and Robben islands, but there were mixed results for the chicks’ health and development. The main cause of a chick being in poor condition is it has not been fed enough by its parents, says Peter Barham, of the University of Bristol.

Lorien Pichegru, a seabird specialist at Nelson Mandela University, says the research has been “subtle but clear. But it was always disregarded by the fisheries science side. In the meantime, we’ve lost half our penguins.”

Waller says: “There’s solid science showing positive benefits for the penguins. Our frustration is that this hasn’t been taken on board by the fisheries department in a satisfactory way and has been contested by the industry.”

The fisheries department did not respond to requests for comment and the South African Pelagic Fishing Industry Association did not want to respond.

A consortium of the World Wildlife Fund South Africa (WWF-SA), Sanccob, the University of Cape Town and Nelson Mandela University have urged Forestry, Fisheries and Environment Minister Barbara Creecy to cease the on-off island closure experiment. Instead, it wants a permanent decision on its recommendation of a minimum of 20km closures around the four colonies in the experiment and for the same 20km closures to be implemented around the colonies at Stony Point in Betty’s Bay and Dyer Island near Gansbaai.

Collectively, these comprise 90% of the penguin breeding population.

Waller says the recommendation is for the fishers to “just fish a bit further away, at a fraction of the area available to them”.

Other known major threats are being addressed, but the shortage of food hasn’t been. “This population is going down a minimum of 5% percent every year,” says McInnes.

Creecy’s department is “deeply concerned” by the rapidly declining penguin population, says spokesperson Zolile Nqayi.

“A central issue thought to be a significant contributor to adult and chick mortality is food availability.

“Related to this is the consideration that limiting fishing around colonies has positive benefits for penguins and other seabirds through increased food availability.”

Last month Creecy met BirdLife South Africa, WWF-SA and Sanccob about an internal scientific report she had requested, which will include descriptions of benefits

for colonies and “potential negative impacts for the fishing industry”.

The South African National Parks is part of a task team set up by Creecy to prevent the extinction of African penguins, says SANParks spokesperson Rey Thakhuli.

“Since 1979, South Africa has lost around 70% of the population, with further steep declines occurring on the West Coast and more recently also on the east coast, particularly at St Croix Island,” he says. “SANParks is hopeful of an outcome that will support the recovery of the population.”

The consortium says estimates of total allowable catches that will be lost for the fishers around Robben and Dassen islands range from 2% to 7% and in Algoa Bay from 6.6% to no associated economic costs.

“However, this shortfall needs to be weighed up against the high socioeconomic value of penguin-based ecotourism and the potential public outcry if no action is taken,” says the consortium.

Waller says the penguins are remarkable seabirds and sentinels of the ocean.

“They are the proverbial ‘canary in the coal mine’ and, right now, the state of the African penguin indicates we have a real problem.”

Craig Smith, the marine programme manager at WWF-SA, says the crisis facing the penguins is symbolic of a far bigger problem in the fishing sector — sardine stocks are at historic lows.

“The industry is not locating the fish anymore and you have penguins and other specialist feeders showing declines in the same period of time. They are all showing similar warning signs that something is not right with the ecosystem.”

Strong lobbying from the fishing sector has focused on job protection, but the “reality is that if South Africa doesn’t manage this fishery well, it will follow Namibia”, whose sardine stocks crashed from overfishing 50 years ago.

“If we get the same situation in South Africa, we’re going to lose jobs irrespectively. There’s an alarm bell ringing and we drastically need to take note,” says Smith.

Original article: https://mg.co.za/environment/2021-05-23 ... gh-to-eat/

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65792

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Threats to African Penguins & Penguin Conservation

Decision time: Will Barbara Creecy put an end to fishing around dwindling penguin colonies?

By Julia Evans• 27 July 2021

African penguins walk on rocks on Boulders beach in Simonstown, South Africa, 14 January 2020. EPA-EFE/NIC BOTHMA

The African penguin is an endangered species. To see if ending fishing around penguin colonies in the Western and Eastern Cape would help protect these birds, islands were closed in an experiment. However, conservationists and the fishing industry assess the results differently. It’s now in the hands of the government.

Environment minister Barbara Creecy has a decision to make – does she allow fishing to continue around endangered penguin colonies or not?

Daily Maverick recently reported on the endangered African penguin and how conservation groups like the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds (Sanccob) and BirdLife SA believe the biggest threat to colonies is prey availability, which is influenced by commercial fishing.

They want Creecy to ban fishing within a 20km radius of the six major penguin colonies – Dassen Island, Robben Island, Stony Point and Dyer Island in the Western Cape, and Bird and St Croix islands in the Eastern Cape.

Their recommendation is based on results of the island closure experiment that ran from 2008 to 2019. It was put in place to see if closing fishing around penguin colonies had a positive effect on penguin populations.

Sanccob, BirdLife SA and academics from Nelson Mandela University support the ban on fishing, based on marine ecologist Dr Richard Sherley’s interpretation of the results of the island closure experiment.

Sherley found that “fishing closures improved chick survival and condition, after controlling for changing prey availability”.

While the results are out, so is the jury.

The South African Pelagic Fishing Industry Association (Sapfia) does not support a ban. Their position is based on UCT’s Prof Doug Butterworth’s recent assessment of the experiment – that closing fishing around colonies had no significant effect on halting the decline in penguin numbers.

Earlier this year, Creecy initiated a process whereby Fisheries, Oceans and Coasts and SANParks would work together to come up with recommendations and scenarios.

“She is going to use what comes out of that process to make a decision on the way forward in terms of island closures. She is taking this issue very seriously, which is great,” says Sanccob’s Lauren Waller.

But who and what should she believe?

The pelagic fishing industry’s perspective

Sapfia agrees that the penguin breeding population is much reduced from what it was at the beginning of the previous century, and that the current rate of decline is a serious concern.

However, based on Butterworth’s assessment of the experiment, they do not think that prey availability caused by consumer fishing is the biggest threat to the birds. Butterworth, a leading international authority in fishery assessment, was contracted by the government to do this research.

Butterworth told Daily Maverick that “the 12-year island closure experiment – carried out at non-trivial expense to the fishing industry – has led to results that show the impact, if any, on the penguins of stopping fishing around some penguin colonies will, at best, be to increase their annual growth rate only by about half-a-percent.”

Conservation groups maintain the biggest threat to the African penguin is lack of prey availability, which is caused by fishing. However, Sapfia disagrees for two main reasons.

First, “the proportion of pelagic fish biomass harvested in South Africa is low compared to small pelagic fisheries elsewhere in the world”.

And second, “the stock biomass is at 60-80% of its potential unfished level. These findings are based in part on credible biannual hydroacoustic surveys carried out by the research vessel, the Africana”.

The African penguin mainly feeds on anchovies and sardines. The pelagic fishery in South Africa is a purse-seine one based predominantly on anchovy, sardine and redeye herring.

Mike Copeland, chairperson of Sapfia, told Daily Maverick that the average catch numbers for anchovies, for the years 1984 to 2020, was about 230,000 tonnes a year.

“This represents about 11% of the average biomass for the same period (2,2 million tonnes),” said Copeland.

And for sardines, “the average catch of adult sardine for the years 1987 to 2020 was about 99,000 tonnes. This represents about 12% of the average biomass for the same period (0,86 million tonnes).”

Butterworth cites a baseline assessment of the SA sardine resource to demonstrate how fishing for sardines doesn’t impact the sardine biomass much: “Typically, fishing reduced abundance by about 20% – that’s way below the international norm for such species, and appreciably less than would be considered a safe (and larger) value to target.”

This study also shows how sardine populations are low now, but they would be low even without fishing.

Butterworth said “fishing is not responsible for the current low abundance – it’s environmental factors (not well understood) which at times can result in poor survival of eggs and larvae – something neither we nor the natural predators can do anything about”.

Butterworth said the abundance of anchovy is “only 20-30% below what it would have been in a no-catch situation”.

Conservation groups’ perspective

In contrast, Sanccob’s Lauren Waller and Alistair McInnes from BirdLife SA do not agree that fishing has no significant impact on prey availability.

“The problem is that there’s a concentration of fishing efforts in areas that are targeted by penguins as well,” said McInnes.

Waller said, “We feel, on the basis of the findings presented by Sherley, and indeed Butterworth, that there is sufficient evidence to justify island closures, particularly at Robben Island, Dassen Island and St Croix Island.

“The results from both modelling approaches are saying similar things – it’s how these results are interpreted that are key.”

McInnes agrees, saying, “Despite all these technical debates, the general results still hold, even in Butterworth’s results.”

The assessments might say similar things, but Butterworth’s shows that closing fishing around the islands will, at best, increase the penguins’ annual growth rate only by about ½%, but Sherley’s assessment showed that it exceeds 1%.

“It’s important to note that the 1% threshold was the pre-agreed threshold by the international panel and the working groups to be the biologically meaningful threshold in the experiments,” said McInnes.

But “there seems to be a dilution of that 1% now that it’s getting to crunch time”.

McInnes says Butterworth’s assessment, which was released in June 2021, “hasn’t had time to be challenged by Sherley’s results. And there are also some questionable methods used to integrate his outputs into that 0.5%”.

Despite the critique from Sapfia and Butterworth, McInnes still insists “there’s more evidence for an effect than no effect.

“The results to date show two to four times more positive results than negative results for island closures. Given the current decline of the birds, the prudent response by the government, in adopting a precautionary approach, would be to protect those waters until such time as there is unequivocal evidence to show the contrary.”

International review panel’s report

In 2020, an international panel reviewed some aspects of the island closure experiment, where they had to answer three questions relating to Butterworth’s and Sherley’s assessments, that considered whether there was merit to their approaches and if they could be used to support decision-making.

“The answer was that both sets of analyses could be used, with the caveat that further work should be done,” said Waller, adding, “this is always going to be the case – it’s the nature of models”.

However, Butterworth argues that “the approach used in the Sherley… article which [the previous Daily Maverick article] cites was wrong, and gave an inflated impression of the accuracy of its results.

“When Sherley corrected his approach to adjust for this, he carried out the computations incorrectly (as the 2020 panel pointed out).”

In response, Waller said, “There have certainly been model adjustments made by Richard Sherley since that publication, but even with these updated analyses that Richard has done, it is pretty much saying the same thing… in fact, providing stronger evidence.”

“Remember, all models are wrong,” Waller told Daily Maverick, citing the common aphorism in statistics, ‘All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

Andre Punt, who has chaired the international review panel for years, told Daily Maverick, “The panel has reviewed the technical details of the work done by Sherley and colleagues, and Butterworth and colleagues, and identified areas where further work was needed – for example, even though some of Sherley’s work had been previously published, we found that further work was needed because of a misunderstanding of the model structure that we advocated.

“I would emphasise that the closure experiment has been unique worldwide. It is somewhat unfortunate that, what I consider to be an excellent way to use science to understand how fishing near colonies impacts penguins, has seen some confused by the arguments about analysis methods.”

A ban’s impact on the fishing industry

A socio-economic study was done by consultants Mike Bergh and Philippe Lallemand to estimate the economic impact on the pelagic fishing industry if the ban were to happen.

Sapfia’s position was that “the monetary value of these losses at just two of the four islands involved in the experiment, Dassen and Robben Islands, was estimated to be R300-million (excluding the economic multiplier effect).

“The small pelagic fishery directly employs more than 5,000 staff in addition to seasonal workers. An increase in overall fishery output of R1-million would be associated with an extra 10.7 jobs in the country’s fishery sector and in the wider economy, and a loss in fishery production would be associated with a corresponding decline in employment.”

Mike Bergh, a scientific consultant to Sapfia, explained that if fishing was closed in a 20km radius around penguin colonies, the fishermen wouldn’t simply be able to fish elsewhere because anchovies are an “opportunity based fishery”.

“Anchovies have to occur in sufficient concentrations close to the surface to be fishable, and those conditions arise from time to time in certain areas.

“So, if you don’t take that opportunity, you may not have another chance. It may just be that this week, that opportunity exists within that closed area.”

Bergh estimates that 23.2% of anchovy catches and 30.1% of sardine catches would lie within the proposed closed area.

The value of the pelagic fishing industry

The pelagic fishing industry provides a cheap source of nutrition that many South Africans rely on.

“The fishery is a major contributor to food security through direct human consumption (e.g. canned fish) or indirect human consumption (e.g. bait or fish meal and oil) and employs a large workforce in fishing and related industries mainly in areas outside the major metropolitan centres,” said Sapfia.

Canned pilchards are an important part of the National School Nutrition Programme and “many of the companies have a contract with various school feeding schemes”, says Sapfia’s Mike Copeland.

A shoal of sardines off Greenpoint, Clansthal on KwaZulu-Natal’s South Coast. (Photo: Natalie dos Santos)

“It’s estimated that every day over 800,000 cans of pilchards are consumed. And that is equivalent to about 3,2 million meals every day.”

Conservation groups like Sanccob believe that the economic loss to South Africa, if the sardine and anchovy stock is depleted and the African penguin (and other seabirds like the Cape gannet) goes extinct, is much bigger than the economic loss to the pelagic fishing industry if the closures went ahead.

In a study commissioned by the City of Cape Town in 2018, Dr Hugo van Zyl and James Kinghorn reported that in 2017, the African penguin colony in Simon’s Town alone brought in 930,000 visitors, created 885 jobs and generated R311-million.

However, Bergh says it doesn’t have to be an either-or situation.

“There is an opportunity for both fishing and the tourism sector to continue to generate revenue for the South African economy.”

Butterworth says, “What is urgently needed is to determine what’s causing this reduction in penguin numbers, and to take actions that (if possible) address those causes, rather than react in a way which will have appreciable negative socio-economic impact, but is very unlikely to result in any meaningful benefit to the penguins.

“Whatever is causing this decline, it almost certainly isn’t fishing around the islands.”

Two African penguins (Spheniscus demersus) cross an empty road during the coronavirus lockdown in the Simonstown suburb of Cape Town, South Africa, 25 April 2020. The African penguin, also known as the Cape penguin, is experiencing a rapid population decline and is classified as ‘endangered’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. EPA-EFE/NIC BOTHMA

In an attempt to get to the bottom of the cause of the decline in penguin numbers, Butterworth has published a study which points at the loss of optimal breeding habitat and burgeoning Cape fur seal populations.

“The penguin population decline may therefore be predominantly the result of competition with seals for food, given that sardine and anchovy constitute important components of seals’ diets, and this competition might also be the primary reason hampering their recovery,” says Butterworth in the study.

However, McInnes says, “there’s been a couple of studies on the relative impacts of seal predation versus prey availability, and prey availability does come up as being more significant. And we are convinced that access to this prey is the biggest limiting factor for the species.”

Final thoughts

It turns out science can be very ambiguous.

“You are seeing what I call management science,” said Andre Punt. “We need to make a decision, but there is more data that could be collected and more analyses conducted, but if we waited for all the data we would like, it would be too late.

McInnes said something similar: “We can go through these results with a fine-tooth comb for years, but every year that we delay taking action, we are losing between 5% and 10% of the penguin population.” DM/OBP

By Julia Evans• 27 July 2021

African penguins walk on rocks on Boulders beach in Simonstown, South Africa, 14 January 2020. EPA-EFE/NIC BOTHMA

The African penguin is an endangered species. To see if ending fishing around penguin colonies in the Western and Eastern Cape would help protect these birds, islands were closed in an experiment. However, conservationists and the fishing industry assess the results differently. It’s now in the hands of the government.

Environment minister Barbara Creecy has a decision to make – does she allow fishing to continue around endangered penguin colonies or not?

Daily Maverick recently reported on the endangered African penguin and how conservation groups like the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds (Sanccob) and BirdLife SA believe the biggest threat to colonies is prey availability, which is influenced by commercial fishing.

They want Creecy to ban fishing within a 20km radius of the six major penguin colonies – Dassen Island, Robben Island, Stony Point and Dyer Island in the Western Cape, and Bird and St Croix islands in the Eastern Cape.

Their recommendation is based on results of the island closure experiment that ran from 2008 to 2019. It was put in place to see if closing fishing around penguin colonies had a positive effect on penguin populations.

Sanccob, BirdLife SA and academics from Nelson Mandela University support the ban on fishing, based on marine ecologist Dr Richard Sherley’s interpretation of the results of the island closure experiment.

Sherley found that “fishing closures improved chick survival and condition, after controlling for changing prey availability”.

While the results are out, so is the jury.