- Between 1970 and 2016, wild populations of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish shrank by 68% on average, according to a new report by WWF and the Zoological Society of London.

- The most catastrophic declines were documented from Latin America and the Caribbean, where populations of monitored species contracted by more than 90% during that 46-year period.

- Among the 3,741 populations of freshwater species they tracked, the researchers found overall declines of more than 80%, underlining the threat from excessive extraction of fresh water, pollution and the destructive impacts of damming waterways.

- The assessment aims to grab the attention of world leaders who will gather virtually for the U.N. General Assembly that kicks off Sept. 15.

Wildlife populations around the world have shrunk by 68% on average in the past nearly 50 years, according to a new report from WWF and the Zoological Society of London.

In that same time, between 1970 and 2016, the human population more than doubled to over 7.4 billion. Humans aren’t just growing in number: human activities are crowding out life from every corner of the planet.

African forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis) at sunrise at Dzanga Bai, Dzanga-Sangha Special Reserve, Central African Republic. Image by Andy Isaacson/WWF-US.

The most catastrophic wildlife declines were documented from Latin America and the Caribbean, where populations of monitored species contracted by more than 90% during that 46-year period, the report says. Freshwater habitats suffered the most profound losses, with population sizes thinning by 84%.

More than 120 experts contributed to the report, tracking over 20,000 populations of nearly 4000 species of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish. The authors clarified that the figures refer to average declines in populations studied, not in the number of individual animals.

Change in land- and sea-use patterns, habitat destruction, and species overexploitation were the biggest threats across continents. The report authors also noted that these factors have also been linked to the growing menace of zoonotic diseases like COVID-19.

“Deforestation has increased significantly across the globe in the last 10 years and so has the trafficking of live wild animals,” Rebecca Shaw, chief scientist at WWF, told Mongabay. “The more we degrade the rainforest, the more we have unfettered deforestation, the more viruses we have spillover into humans.”

Illegal and poorly regulated trade in wild animals increases the chances of diseases found in animals jumping to humans, experts say.

But this trade in animals coveted by humans is also leading to their decimation. African gray parrots (Psittacus erithacus) have, for example, all but disappeared from Ghana. With its dazzling ability to mimic human speech, the bird is a hugely popular pet. Trade in the parrots was banned in 2016. Illicit exports and loss of their forest habitat have sealed the bird’s fate in the West African nation.

A mountain gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei) family in Virunga National Park, Democratic Republic of Congo. Image by Brent Stirton/Reportage for Getty Images/WWF.

A population of eastern lowland gorillas (Gorilla beringei graueri) endemic to the Democratic Republic of Congo, which lives in Kahuzi-Biega National Park, saw its numbers fall from 17,000 in 1994 to less than 4,000 in 2015. They are heavily poached, and their habitats are severely degraded by artisanal mining.

It’s not just terrestrial landscapes that are changing; rivers and wetlands are being transformed by excessive extraction of freshwater, pollution, damming, overfishing, and invasive species.

Between 1982 and 2015, the Chinese sturgeon (Acipenser sinensis), which can grow to a hefty 30 kilograms (66 pounds), nearly vanished from China’s Yangtze River after the waterway was dammed. Among the 3,741 populations of species found in freshwater habitats, the researchers saw overall declines of more than 80%.

“Water systems are so vulnerable because water is a basic resource for humans, no matter where you are,” Shaw said, noting that 70% of freshwater is extracted for agricultural use.

The findings echo multiple reports released in recent years, which, though they use different metrics, capture the same phenomena: the Earth is witnessing a dramatic loss of biodiversity. Last year, the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) warned that more than a million species of plants and animals face extinction.

A Malagasy dwarf chameleon (Brookesia micra), the world’s smallest chameleon. It is found in the Nosy Hara archipelago in Madagascar. Image by Nick Riley/WWF-Madagascar.

Their analysis showed that about 2 billion hectares (5 billion acres) of land is degraded, and humans have already altered two-thirds of the oceans. More than 80% of wetlands and half of the world’s coral reefs, called the rainforests of the seas because of the high level of biodiversity they host, are also in peril.

The new publication is based on the Living Planet Index developed by ZSL, which uses data for vertebrates, a well-studied group.

The assessment aims to grab the attention of world leaders who will gather virtually for the U.N. General Assembly that kicks off Sept. 15. It will be the first online summit in the 75 years of the General Assembly, which brings together heads of state and government from all 193 U.N. member states.

“With leaders gathering virtually for the UN General Assembly in a few days’ time, this research can help us secure a New Deal for Nature and People which will be key to the long-term survival of wildlife, plant and insect populations and the whole of nature, including humankind,” Marco Lambertini, director-general of WWF International, said in a statement. “A New Deal has never been needed more.”

A Galapagos sea lion at the Puerto Ayora fish market. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

Progress on key global pacts will be discussed at the meeting, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Paris Agreement, and the U.N.’s Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

The CBD is the most closely aligned with the goal of safeguarding biodiversity. A post-2020 agenda is currently being hashed out under the international agreement that will define the relationship between the natural environment and human communities for the next decade. It will also lay the groundwork for a road map that extends until 2050.

The CBD’s next conference of parties was supposed to be held in China this year, but has been postponed because of the pandemic and is now scheduled for May next year. In discussions held earlier this month, in an unprecedented move, parties agreed to recognize and advance the rights of nature.

However, some like Andy White, coordinator at the Rights and Resources Initiative, a coalition which promotes the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, criticized the WWF report for putting “nature, and not local people and their rights and livelihoods, at the center of their conservation strategies.” White argued that there is robust evidence to show that these groups are better at preserving forests and biodiversity than governments.

“By ignoring local people once again, or assuming their compliance with the northern notions of conservation, in this case too ‘silence is violence’ and there is a risk that the report will do damage to the very people who have been protecting the nature they deserve and we all need,” he said.

Others, highlighted the inequities in the way the loss of ecosystem services impacts communities. “These numbers confirm a message that previous reports have presented, we are undermining nature globally with cascading effects and unequal consequences for regions and localities,” Eduardo S. Brondizio, an anthropologist at Indiana University Bloomington, said.

Brondizio, one of the authors of the IPBES report, added that “that biodiversity is not out there, isolated from the lives of people, but it is part of a broader chain that sustain our quality of life, and also it is also closely connected to the choices we make as society.

A Global Biodiversity Outlook will also be released at the U.N. summit, which is expected to focus on policies and actions needed to arrest and reverse humanity’s runaway destruction of the natural world.

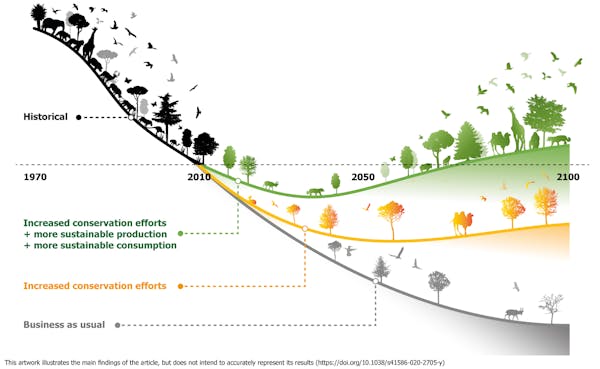

Shaw at WWF said she was looking not just at world leaders but also at people, to bring about a change. “Conservationists alone can’t do it, we have to tackle climate change, and we have to tackle the way we produce and consume food and fibre in particular,” she said.”Tackling the production of food and the consumption of food, and the waste in the food supply chain is going to be really important.”

Citation:

Almond, R. E. A., Grooten, M., & Petersen, T. (2020). Living Planet Report 2020: Bending the curve of biodiversity loss. WWF.

(Editor’s note: The post has been updated to include comments from Andy White at the Rights and Resources Initiative and Eduardo S. Brondizio at Indiana University Bloomington.)

Malavika Vyawahare is a staff writer for Mongabay. Find her on Twitter: @MalavikaVy