By Don Pinnock• 14 September 2021

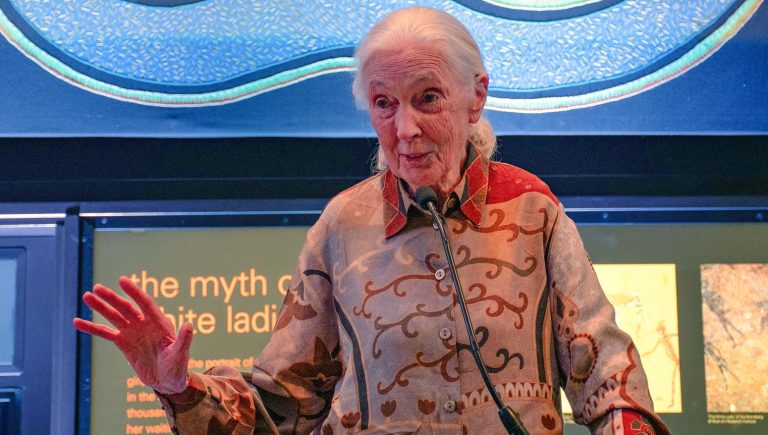

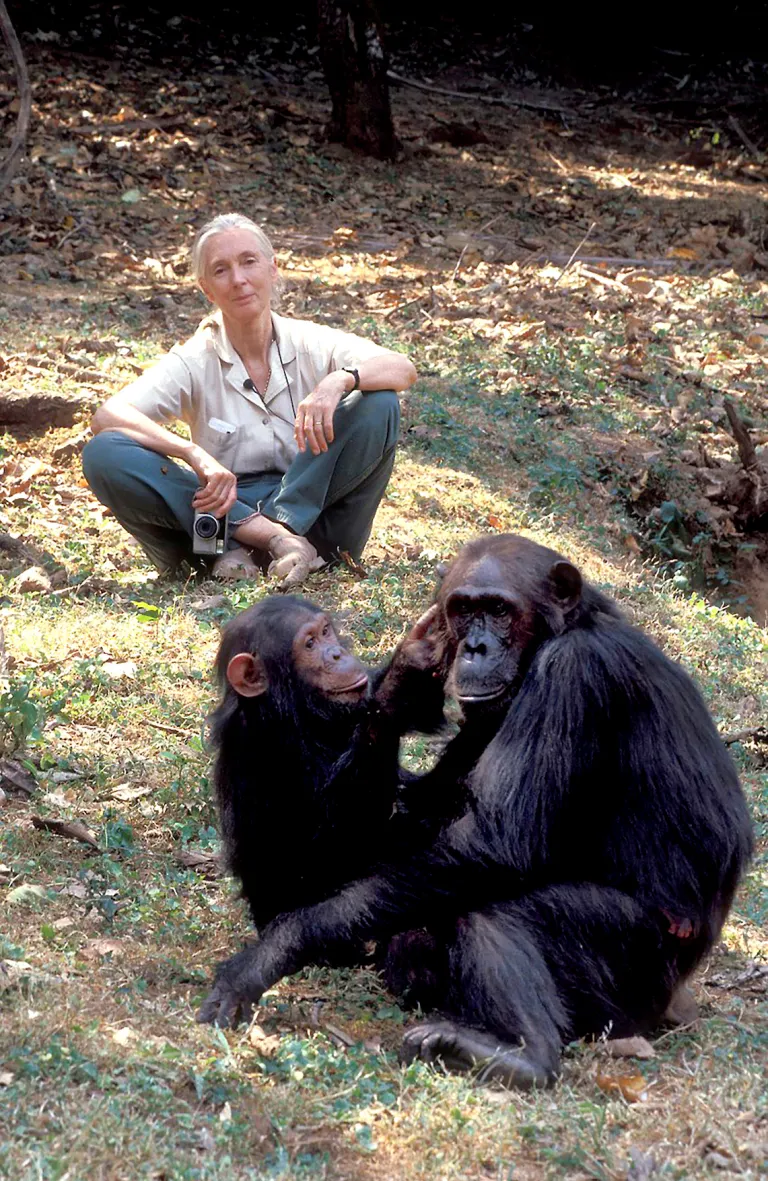

Wangari Maathai was a Kenyan environmental activist and the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize. (Photo: Supplied)

‘If I have learned one thing, it is that humans are only part of this ecosystem. When we destroy the ecosystem, we destroy ourselves, for on its survival depends our own.’

One day, back in the 1940s, on the patch of land cultivated by her family near Mount Kenya, Wangari Maathai planted a tree. For most people, the reason would be to grow a tree. For Maathai it would grow into a movement for global reforestation.

“The planting of trees is the planting of ideas,” she would later tell all who would listen – and many did. “By starting with the simple step of digging a hole and planting a tree, we plant hope for ourselves and for future generations.” She had a way with words. But the trouble she would get into on behalf of trees was considerable.

Born in 1940 in the rural village of Ihithe in Kenya’s Nyeri District, Maathai grew up in a very traditional family. She was the third of six children and the first girl after two sons to the second of her father’s four wives.

Her father was a farmer and her mother performed the expected tasks of a woman at that time: raising children, cooking, and fetching water. Both parents were imbued with a rich knowledge of the land and the traditions of her rural Gukuyu ancestry.

The area would become the epicentre of resistance to colonialism and the imposition of colonial taxation, the birthplace of renowned Mau Mau freedom fighters. And one formidable tree warrior.

In her biography, Unbowed, Maathai remembers: “When my mother told me to go and fetch firewood, she would warn me, ‘Don’t pick any dry wood out of the fig tree, or even around it.’

“‘Why?’” I would ask.

“‘Because that’s a tree of God,’ she’d reply. ‘We don’t use it. We don’t cut it. We don’t burn it.’”

Forever after, fig trees would stand for her as totems of environmental health.

Wangari Maathai was the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize. (Photo: Supplied)

Maathai later moved with her family to a settler’s farm where her father got a job. At her elder brother’s insistence, she attended school and later a Catholic seminary. As part of what became known as the Kennedy Airlift, she was given a bursary to study in the US, earning a master’s degree in biology from the University of Pittsburgh in 1966.

But after returning to Kenya, she found that her career opportunities as a woman were limited. As an alternative, she chose to further her education, which led to a doctorate in the field of veterinary science from the University of Giessen in 1971, a first for an East African woman. She became an associate professor at the University of Nairobi.

But things were changing in the countryside. The colonial government had driven a shift from peasant farming to intensive commercial mono-crop agriculture, creating a landed class it hoped would form a buffer between the radical Gikuyu members and the government, minimising support for the Mau Mau rebellion. The practise was continued after independence with the introduction of cash crops such as coffee, tea, pyrethrum, and the introduction of exotic dairy cows.

These land reforms changed the social, economic, political and ecological landscape of central Kenya and affected village life and the environment where Maathai grew up.

“I saw rivers silted with topsoil, much of which was coming from the forest where plantations of commercial trees had replaced indigenous forest.”

She wrote of a visit home. “I noticed that much of the land that had been covered by trees, bushes and grasses when I was growing up had been replaced by tea and coffee.

“I also learned that someone had acquired the piece of land where the fig tree I was in awe of as a child had stood. The new owner perceived the tree to be a nuisance because it took up too much space and he felled it to make room to grow tea.

“By then I understood the connection between the tree and water, so it did not surprise me that, when the fig tree was cut down, the stream where I had played with the tadpoles dried up.”

Wangari Maathai realised that tree planting was fundamental to civic education, political advocacy, community empowerment, economic sustainability and global biodiversity. (Photo: Supplied)

On visits home, Maathai found the women were running out of wood. They blamed others, they blamed the government, but Maathai saw it another way.

“Think of what we ourselves are doing,” she told them. “We are cutting down the trees of Kenya. When the soil is exposed, it’s crying out for help, it’s naked and needs to be clothed in its dress. That’s the nature of the land. It needs colour, it needs its cloth of green. Why not plant trees?”

Right there the concept of the Green Belt Movement was conceived. It began with the planting of seven saplings in 1977 and training women to care for the land. At the time Maathai would have had no idea about the implication of those actions: if you planted trees, you were also obliged to protect them.

She soon realised that tree planting was fundamental to civic education, political advocacy, community empowerment, economic sustainability and global biodiversity. She was able to make those sorts of connections. As the movement spread, it engaged with environmental destruction and poverty in Kenya. And central to its work was the empowerment of rural women. They began flexing their political muscle – to the horror of the repressive, male-dominated government of Daniel arap Moi.

In 1992 the Green Belt Movement opposed a 60-storey development, the Kenya Times Media Trust Complex, from being built in Uhuru Park, a 34-acre public green space in the centre of Nairobi. “We need a park more than an office tower,” she told the press.

Maathai, with many of the women, was arrested on charges of sedition and treason. While she was out on bail, Uhuru Park became the site of a hunger strike to secure the release of political prisoners. Maathai was beaten unconscious by police. In 1999 she was beaten again when she and other women planted oak saplings to protest the privatisation of Karura Forest in Nairobi.

Her husband, who served in the government, divorced her, finding he was culturally unable to live with an “educated woman” and troublemaker.

Then the government changed. Maathai ran for political office and was elected as an MP and then deputy minister of environment. But by then she had raised her sights from Kenya to combating environmental destruction worldwide. Along the way, she helped to write her country’s new Constitution, ensuring the right of all citizens to a clean and healthy environment.

In 2004 Maathai became the first African woman and the first environmentalist to be given the Nobel Peace Prize, in recognition of her work for sustainable development, democracy and peace. In announcing the award, the Norwegian Nobel Committee said that, “Maathai stands at the front of the fight to promote ecologically viable social, economic and cultural development in Kenya and in Africa.”

A plaque commemorates the life of Wangari Maathai. (Photo: Supplied)

Two years later she joined with the United Nations Environment Programme to launch a campaign to plant a billion trees around the world. In 2007 she became co-chair of the Congo Basin Forest Fund and in 2009 she was designated a United Nations messenger of peace by Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon.

The Guardian would report that by then she had “coaxed the Mexican army, Japanese geishas, French celebrities, 10,000 Malaysian schools, the president of Turkmenistan and children in Rotherham to roll up their sleeves, dig a hole and plant trees”.

Maathai was simply unstoppable. She addressed the UN General Assembly, carried the flag at the Olympic Games and, as her campaign for trees rolled ahead, she accepted many citations and awards. The list of her awards, affiliations and honorary awards is extraordinary.

Through her dedication, winning smile and tactical intelligence she had managed to put deforestation high on the agenda in developing countries and made tree planting an act of transformation in which everyone could engage.

The Green Belt Movement had kicked off one of the world’s largest mobilisations of people for a cause. In Kenya to date, 55 million trees have been planted, mainly by grassroots women. In Maathai’s name, almost 50 countries have planted 1.5 billion trees, with a goal of 14 billion.

Countries were falling over themselves to plant the most and be linked with Maathai: Indonesia claimed to have planted 79 million in a day. Turkey said it had planted 500 million, Mexico 250 million. India pledged to replant six million hectares of degraded forest.

Such was the Wangari Maathai effect. And it all started with a woman planting a tree and an idea. “I saw that the Earth was naked,” she told an interviewer. “For me the mission then was to try to clothe, cover the earth; cover the ground with green.”

During her last days, as she battled ovarian cancer in a Nairobi hospital, Maathai insisted that she not be buried in a wooden coffin – affirming her life-long battle to save trees and the rest of the environment.

When she died in 2011, the Nigerian environmental activist Nnimmo Bassey wrote: “Even if no one applauds this great woman of Africa, the trees will clap.” But the world did applaud and millions mourned.

The daughter of a peasant farmer had become a legend. DM/OBP