From left: Diatoms | Prosobranchia | Trachylina | Lichens. (Images: Supplied)

By Don Pinnock | 23 Nov 2021

Ernst Haeckel couldn’t make up his mind which of his great loves to follow: science or art. But, peering into a microscope one day, he chose both. It was to change our perception of art, architecture and the natural world.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The 19th century was the age of machines. Scientific innovation and raw materials extracted from expanding colonial conquest transformed Europe from an agrarian, feudal subcontinent into a powerhouse of wealthy national states jostling for supremacy.

In the century that followed, this culminated in horrific wars. But, while the good times lasted, the 19th century would midwife extraordinary creativity in engineering, science, art and architecture. This innovation was indexed by “movements” which embraced different trends and responded and reacted to various tendencies.

Anthomedusa. (Photo: Supplied)

Romanticism was an early starter, turning its back on the industrial revolution and towards a medieval golden age. Neoclassicism found its inspiration in the art and architecture of ancient Greece and Rome.

Modernism embraced the emerging industrial world of urbanisation, new technologies and war. The Arts and Crafts Movement and Pre-Raphaelites revolted against the crudity of industrial mass production, turning towards hand-crafted and hand-dyed designs, meticulous patterning and almost photographic art glorifying the human form.

Ascidians. (Photo: Supplied)

Art Nouveau sought inspiration, not in human endeavour, but the beauty of the natural world. It was inspired by forms such as the sinuous curves of plants and microscopic creatures, finding its way into an extraordinary variety of applied arts. In Germany, it was known as Gesamtkunstwerk (“total work of art”).

Frogs. (Photo: Supplied)

The movement was expressed through the designs of people like Gustav Klimt, Antoni Gaudi, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Alphonse Mucha. It created dynamism and movement through filigree structures, whiplash lines and the use of materials such as iron, glass, ceramics and later concrete.

Lichens. (Photo: Supplied)

From around 1890 to World War 1, Art Nouveau had a huge influence on architecture, interior design, graphic arts, furniture, glass art, textiles, ceramics, jewellery and metalwork.

Lizards. (Photo: Supplied)

Its high point was the Paris Exposition in 1900. Nearly 50 million visitors passed through its gate beneath an enormous, lace-like Art Nouveau arch created in iron by the architect René Binet based on the skeleton of a microscopic radiolarian. The Exposition made Art Nouveau famous around the world.

Medusa. (Photo: Supplied)

The inspiration for the arch — and for much of Art Nouveau — was the work of Ernst Haeckel, a German zoologist whose passion for science and art was to produce an outpouring of nature-based design.

Nepenthes. (Photo: Supplied)

Haeckel was born in Potsdam in 1834 and his father insisted that he study to become a doctor. He complied, completed his studies and took on a few patients, but found it increasingly irksome. Other passions were calling.

Orchids. (Photo: Supplied)

He shifted his attention to zoology which better suited his athletic and adventurous nature, but art also demanded his attention. However, it seemed to have no place in the scientific world. Which way to turn?

Prosobranchia. (Photo: Supplied)

In search of a scientific project, the young Haeckel set off to Italy where he met German poet and painter Hermann Allers. Influenced by his new friend, Haeckel abandoned his research quest and took up life as an artist, despite increasing threats from his father back in Germany and the despair of his increasingly impatient fiancée, Anna.

Then one day a fisherman brought him buckets of water containing minute invertebrates. Gazing at them under his microscope, Haeckel was transfixed by their beauty. He was looking at the bodies and skeletons of radiolarians, marine creatures nobody had ever seen before. Their variation and geometry were extraordinary and he began sketching and painting them.

Radiolarians. (Photo: Supplied)

He had found the synergy between science and art, his heart and his head — and also a future profession. The tiny marine creatures were, he said, delicate works of art, colourful gems, unfailingly beautiful.

In the space of a few weeks, with mounting excitement, he identified more than 60 new species and even new families. Within a month more than 100. Each day, with pencil and paintbrush, he rendered them on to paper, not haphazardly, but with an innate sense of structure in their placement. The whole was as beautiful as its parts.

Siphonophorae. (Photo: Supplied)

To know nature, he insisted, science needed to really see it. He was, he wrote to Anna, in a unique position to make this possible through his scientific understanding and artistic ability.

Echoing the scientist Alexander Humboldt, a man he greatly admired, Haeckel would tell anyone who’d listen that nature could only be understood as a unified whole made up of complex interrelationships. He would later create a word for this understanding: ecology, from the Greek word oikos — household.

Trachylina. (Photo: Supplied)

Haeckel went home, married Anna and became a professor of zoology at the University of Jena. His career would expand over many areas of natural history and science.

Diatoms. (Photo: Supplied)

He didn’t shy away from grand theories and philosophical controversy as can be seen from the titles of some of his books: The History of Creation, The Riddle of the Universe, Crystal Souls and The Wonders of Life. He produced more than 1,000 illustrations which were wonders of detail and accuracy.

The deep core of his work, though, was his two-volume General Morphology of Organisms — 1,000 pages about evolution, natural selection and the shape of living creatures which Darwin described as magnificent.

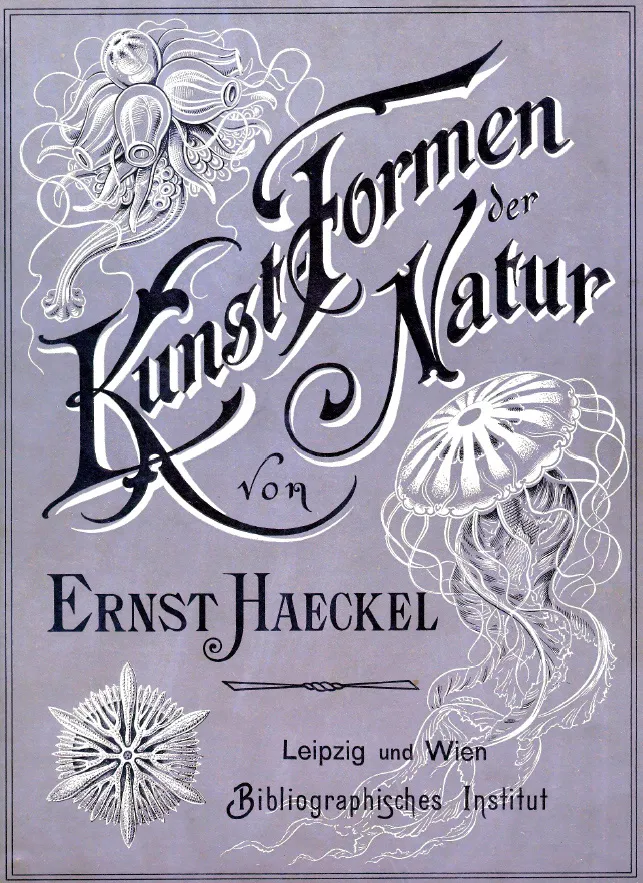

Cover of ‘Kunst Formen von der Natur’, by Ernst Haeckel. (Photo: Supplied)

Then, in 1900, Haeckel published Art Forms in Nature which contained 100 of his finest illustrations showing the “hidden treasures” of nature. It was hugely influential and translated into 27 languages. The book was to become the visual vocabulary of the artists, architects and craftspeople who were the creative heart of Art Nouveau.

Gallé glass. (Photo: Supplied)

The famous French glass artist Émile Gallé said Haeckel’s “marine harvest” had turned scientific laboratories into studios for the decorative arts. Gaudi, who designed the breathtaking Sagrada Familia (Holy Family Church) in Barcelona, magnified Haeckel’s marine organisms into bannisters, arches and stained-glass windows. René Binet, who designed the monumental arch for the Partis Fair, published a book that showed how Haeckel’s illustrations could be transformed into interior decoration.

Sagrada Familia, Barcelona. (Photo: Supplied)

Sagrada Familia detail. (Photo: Supplied)

Sagrada windows. (Photo: Supplied)

Sagrada stained glass. (Photo: Supplied)

In her magnificent biography of Alexander Humboldt — The Invention of Nature — Andrea Wulf devotes a chapter to Haeckel. “As humankind dismantled the natural world into ever smaller parts — down to cells, molecules and then atoms,” she writes, “Haeckel believed that this fragmented world had to be reconciled in the unity of nature.” For him, there was no division between the organic and the inorganic world.

For Haeckel, she writes, “the goddess of truth lived in the temple of nature… as long as there were scientists and artists, there was no need for priests and cathedrals.” Soaring trees were his temple, columns and tropical lianas the fabric. Altars were aquaria filled with delicate corals and colourful fish.

Art Nouveau and its artists, architects and crafters are remembered through their works that are with us still. The man who inspired them is hardly known, but his extraordinary images live on and can be downloaded here. DM/OBP