‘Black Lion’ is an inspirational walk on the wild side

Posted: Tue Jan 25, 2022 5:47 pm

Book Review

By Ed Stoddard | 23 Jan 2022

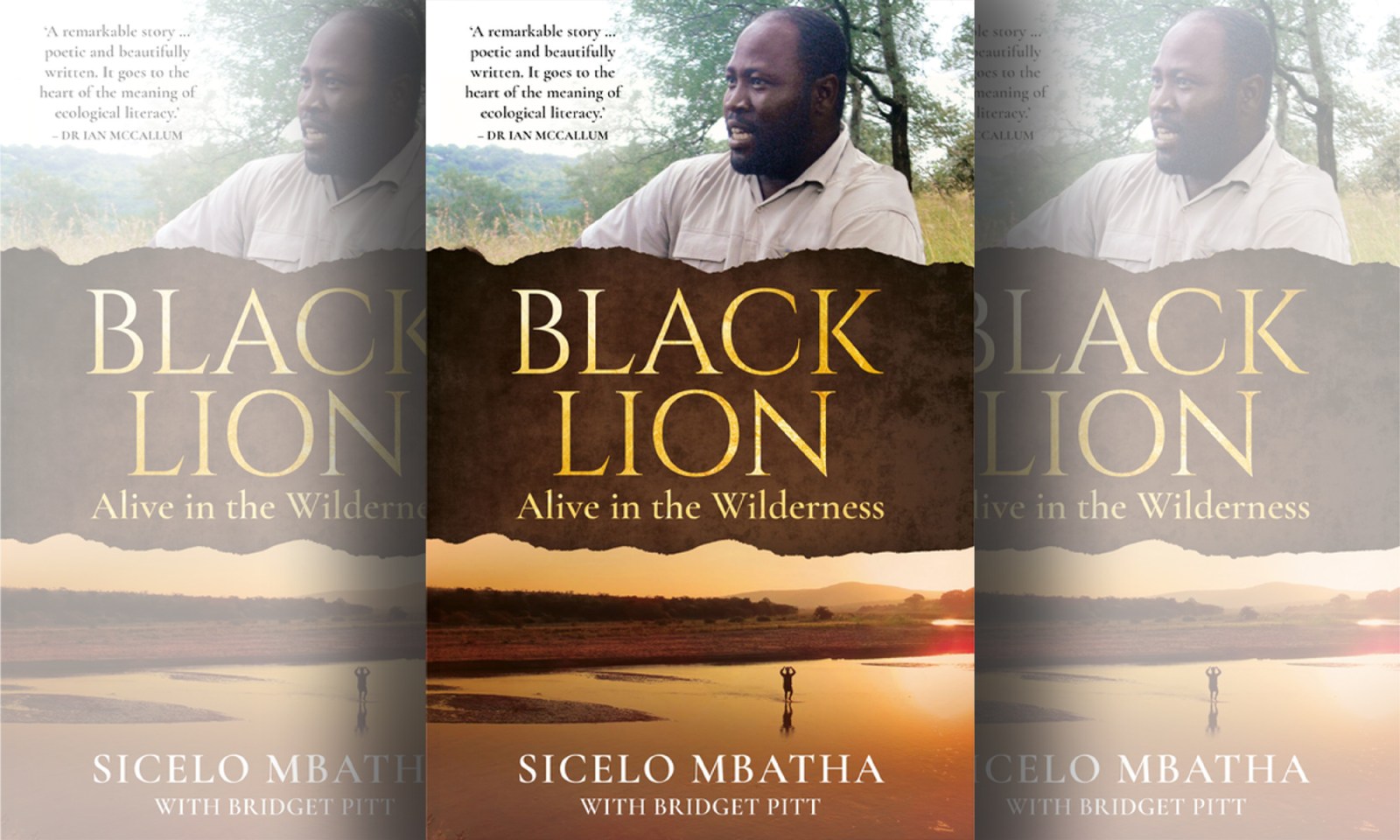

South African wilderness guide Sicelo Mbatha believes that journeys into the wild should be a healing and spiritual experience. In Black Lion: Alive in the Wilderness – co-authored with Bridget Pitt – he traces his own path into the wild. As a black trail guide and author, he brings an important perspective to African conservation that is missing from most accounts of this nature.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This lyrical and heartfelt book helps to fill a yawning gap in African natural history prose. The overwhelming majority of such books have been written by white authors, underscoring a wide cultural divide.

I have written before that while much of this literature is excellent and informative, a lot of it also romanticises African wildlife, perpetuating misleading Disney stereotypes about the continent’s fauna. Some of it has also been downright racist, playing into Tarzan-like images of Africa and relegating Africans to dispensable “stand-ins” on the set, or objects of pity.

Sicelo Mbatha is a Zulu man from a poor rural background, and he brings an important perspective to African conservation that is missing from most accounts of this nature. The book is written with author and conservationist Bridget Pitt – two writers from very different backgrounds who have found common ground in the wild. As such, this fine book follows a trail blazed by “Changing a Leopard’s Spots: The Adventures of Two Wildlife Trackers”, co-authored by Alex van den Heever and Renias Mhlongo.

And where other black writers have ventured into the world of conservation, it has been more focused on the social side – which is vital, as wildlife and human society are often regarded separately from anthropogenic impacts on the environment. Jacob Dlamini’s excellent social history of the Kruger National Park, “Safari Nation”, is an example on this front.

Growing up on the edge of the famed Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Game Reserve in KZN – where his father worked as a stable hand, looking after patrol horses – Mbatha’s childhood friends were perplexed by his early ambitions to be a game ranger.

“They couldn’t believe that, after spending so much time in the bush as a cow herder, I was dreaming of spending yet more time in the bush. I could not blame them, as the apartheid regime’s ‘Bantu education’ did not encourage us to work with nature.

“In fact, they would make us work in the school garden to punish us if we were late for class. This taught us that working with the soil was punishment, something undignified,” he writes.

Among other things, this highlights the roots of the cultural divide giving rise to the often conflicting perceptions of wildlife and “the bush” between Africans and non-Africans. This is one of the many telling insights sprinkled throughout this narrative.

Mbatha had good reason growing up to be wary of wildlife and even abhor it. At the age of seven, while crossing a river on his way home from school, his older friend Sanele was wrenched from his hand by a crocodile, never to be seen again. This was a horrific experience for a child to endure, one that often happens across Africa. For weeks after, he was despondent and could not sleep or eat – classic signs of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Years later, while watching crocodiles eat a still-alive Cape buffalo that was stuck in a mud pool – a truly nightmarish scene – he had an epiphany of forgiveness for the species. He realised the croc that had taken his friend did not do so out of malice, but was simply following its predatory nature.

It takes a special person to reach such a conclusion about a reptile that is widely regarded in rural Africa with fear and loathing.

Mbatha is unsparing in his criticism of the corruption and cronyism that have undermined the promise of post-apartheid South Africa. He lost out on a bursary because of corruption at the Department of Education. Yet this setback did not deflect him from his path. He worked for years as a volunteer at Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, sacrificing income in pursuit of his goal and his love affair with the wild. It would pay off when he was eventually accepted into the Wilderness Leadership School in Durban, which would qualify him to become a field guide.

He would then leave Ezemvelo in 2014 to found his own company, uMkhiwane Ecotours, now uMkhiwane Sacred Pathways.

For Mbatha, the trail experience should be one of healing and a reconnection with nature, and not a pursuit of “cheap thrills” (let’s find a python and leopard in a battle to the death!), with Big Five sightings ticked off. This is something that many outdoor and wilderness enthusiasts can relate to, and while it may also seem like a romantic take on the wild, there is nothing wrong with that.

This reviewer – from a very different cultural background growing up in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia – can relate to Mbatha’s adolescent yearnings for the bush, which I shared at that age. It may lead to different pursuits, but the paths will still take us into the forest or the veld.

There are minor quibbles with some of Mbatha’s takes on things, though. His views on “the respect shown to nature” by indigenous peoples, and how across the globe they allegedly lived in “harmony” with nature, is ahistorical. The Americas and, for that matter, Africa, were hardly examples of untouched wilderness before Europeans arrived on the scene. These environments were already profoundly changed by human activities and there are far too many examples to list here. The adoration of cattle among the Zulu, which Mbatha can clearly relate to, is one. Cattle are not native to southern Africa and their introduction in the region has had lasting ecological consequences that began before the arrival of the first white settlers.

But Mbatha, who clearly has a passionate curiosity, is also not wrong in his assertion that there is much wisdom to be gleaned from the outlooks and traditions of native peoples around the world. And he does have a critical cast of mind, aiming arrows at his own Zulu culture for, among other things, their past treatment of the San.

This is an important book that brings a sorely needed framework to the discourse on African conservation. It is also a delightful read, with plenty of outdoor adventure and hair-raising encounters with wildlife.

A satisfying journey into the wild, indeed. DM/ML

By Ed Stoddard | 23 Jan 2022

South African wilderness guide Sicelo Mbatha believes that journeys into the wild should be a healing and spiritual experience. In Black Lion: Alive in the Wilderness – co-authored with Bridget Pitt – he traces his own path into the wild. As a black trail guide and author, he brings an important perspective to African conservation that is missing from most accounts of this nature.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This lyrical and heartfelt book helps to fill a yawning gap in African natural history prose. The overwhelming majority of such books have been written by white authors, underscoring a wide cultural divide.

I have written before that while much of this literature is excellent and informative, a lot of it also romanticises African wildlife, perpetuating misleading Disney stereotypes about the continent’s fauna. Some of it has also been downright racist, playing into Tarzan-like images of Africa and relegating Africans to dispensable “stand-ins” on the set, or objects of pity.

Sicelo Mbatha is a Zulu man from a poor rural background, and he brings an important perspective to African conservation that is missing from most accounts of this nature. The book is written with author and conservationist Bridget Pitt – two writers from very different backgrounds who have found common ground in the wild. As such, this fine book follows a trail blazed by “Changing a Leopard’s Spots: The Adventures of Two Wildlife Trackers”, co-authored by Alex van den Heever and Renias Mhlongo.

And where other black writers have ventured into the world of conservation, it has been more focused on the social side – which is vital, as wildlife and human society are often regarded separately from anthropogenic impacts on the environment. Jacob Dlamini’s excellent social history of the Kruger National Park, “Safari Nation”, is an example on this front.

Growing up on the edge of the famed Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Game Reserve in KZN – where his father worked as a stable hand, looking after patrol horses – Mbatha’s childhood friends were perplexed by his early ambitions to be a game ranger.

“They couldn’t believe that, after spending so much time in the bush as a cow herder, I was dreaming of spending yet more time in the bush. I could not blame them, as the apartheid regime’s ‘Bantu education’ did not encourage us to work with nature.

“In fact, they would make us work in the school garden to punish us if we were late for class. This taught us that working with the soil was punishment, something undignified,” he writes.

Among other things, this highlights the roots of the cultural divide giving rise to the often conflicting perceptions of wildlife and “the bush” between Africans and non-Africans. This is one of the many telling insights sprinkled throughout this narrative.

Mbatha had good reason growing up to be wary of wildlife and even abhor it. At the age of seven, while crossing a river on his way home from school, his older friend Sanele was wrenched from his hand by a crocodile, never to be seen again. This was a horrific experience for a child to endure, one that often happens across Africa. For weeks after, he was despondent and could not sleep or eat – classic signs of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Years later, while watching crocodiles eat a still-alive Cape buffalo that was stuck in a mud pool – a truly nightmarish scene – he had an epiphany of forgiveness for the species. He realised the croc that had taken his friend did not do so out of malice, but was simply following its predatory nature.

It takes a special person to reach such a conclusion about a reptile that is widely regarded in rural Africa with fear and loathing.

Mbatha is unsparing in his criticism of the corruption and cronyism that have undermined the promise of post-apartheid South Africa. He lost out on a bursary because of corruption at the Department of Education. Yet this setback did not deflect him from his path. He worked for years as a volunteer at Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, sacrificing income in pursuit of his goal and his love affair with the wild. It would pay off when he was eventually accepted into the Wilderness Leadership School in Durban, which would qualify him to become a field guide.

He would then leave Ezemvelo in 2014 to found his own company, uMkhiwane Ecotours, now uMkhiwane Sacred Pathways.

For Mbatha, the trail experience should be one of healing and a reconnection with nature, and not a pursuit of “cheap thrills” (let’s find a python and leopard in a battle to the death!), with Big Five sightings ticked off. This is something that many outdoor and wilderness enthusiasts can relate to, and while it may also seem like a romantic take on the wild, there is nothing wrong with that.

This reviewer – from a very different cultural background growing up in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia – can relate to Mbatha’s adolescent yearnings for the bush, which I shared at that age. It may lead to different pursuits, but the paths will still take us into the forest or the veld.

There are minor quibbles with some of Mbatha’s takes on things, though. His views on “the respect shown to nature” by indigenous peoples, and how across the globe they allegedly lived in “harmony” with nature, is ahistorical. The Americas and, for that matter, Africa, were hardly examples of untouched wilderness before Europeans arrived on the scene. These environments were already profoundly changed by human activities and there are far too many examples to list here. The adoration of cattle among the Zulu, which Mbatha can clearly relate to, is one. Cattle are not native to southern Africa and their introduction in the region has had lasting ecological consequences that began before the arrival of the first white settlers.

But Mbatha, who clearly has a passionate curiosity, is also not wrong in his assertion that there is much wisdom to be gleaned from the outlooks and traditions of native peoples around the world. And he does have a critical cast of mind, aiming arrows at his own Zulu culture for, among other things, their past treatment of the San.

This is an important book that brings a sorely needed framework to the discourse on African conservation. It is also a delightful read, with plenty of outdoor adventure and hair-raising encounters with wildlife.

A satisfying journey into the wild, indeed. DM/ML