The sad truth is, most humans don’t give a damn about nature

Posted: Thu Dec 08, 2022 3:25 pm

Ivory ornaments are displayed in London in 2014, during an event involving the public destruction of ivory before an international conference on illegal trade in wildlife. (Photo: Carl Court / AFP)

By Don Pinnock | 06 Dec 2022

Two international conferences dealing with the crisis of the natural world have just ended: one about climate, the other about the use of wildlife. Both issues are code red for the future of life on earth, but both conferences were hollowed out by corporate greed. Next up is one about biodiversity. Don’t hold your breath.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The problems of human impact on the natural world are too big, too complex for ordinary people like us to deal with. If we care, we have to rely on scientists, politicians, lobbyists, NGOs and global multilateral conferences to put things right.

Most people don’t care, of course; they’re too busy just getting through the week or year and in many cases simply surviving. Mostly they live in cities and nature is somewhere else, unseen, unfelt. Somebody else’s problem.

But here’s the thing: those we hope to trust with the future of Earth’s systems are letting us down badly, and leaving us (to use an Australian expression) up shit creek in a barbed-wire canoe.

Take CITES — the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora — which has been going for nearly half a century. Its 14th congress was held in Panama last month with the flights of thousands of delegates spewing tonnes of CO2.

What it claims to do is prevent the exploitation of wild things as objects of trade and to protect endangered species. It has no policing function, so works by consensus among its 184-nation members.

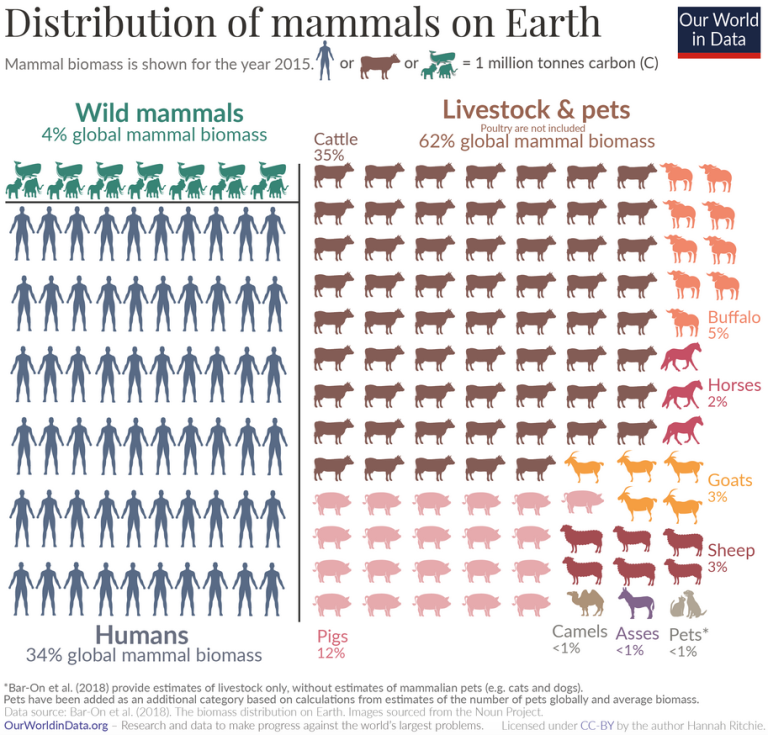

CITES, it has to be said, hasn’t been very successful, especially with mammals. Of the planet’s total mammal biomass, only around 4% are wild.

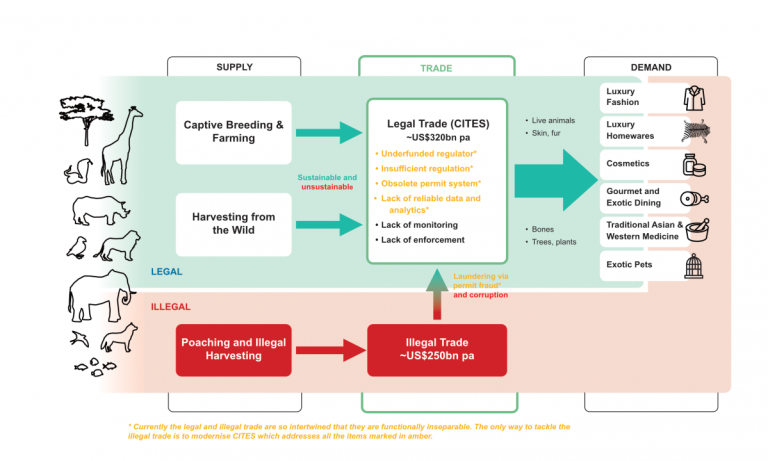

The point isn’t that it’s not succeeding, but that it appears to be set up to fail. CITES has levels of protection related to species. To export or import requires a permit, and trade in some endangered species is forbidden.

Permits are pieces of paper filled in with ballpoint pens in remote parts of the world or in dark offices by lesser officials. They can be forged — cheating is endemic and illicit trade carries on unhindered.

A report by Nature Needs More cites a study it commissioned which concluded that the CITES trade database “was the worst designed and most impenetrable data source they have ever investigated”.

A digital permitting system would stop all that, but it has not been implemented, though often promised. There appears to be a reason.

Legal and illegal trade

The legal supply of captive breeding, wild farming and harvesting from the wild amounts to around $320-billion a year. The trade from illegal poaching and harvesting comes to about $250-billion a year.

Most of these products go to developed countries to fill the demand for luxury fashion and homewares, cosmetics, exotic dining, traditional medicine and exotic pets.

In pursuit of wildlife products, developed countries cannot do without the illegal trade.

It’s impossible to verify meetings that take place in offices, coffee shops or bars between CITES employees, poachers, smugglers and corporate representatives, but the outcome is glaringly obvious. In the wildlife business, CITES is fit for purpose.

At its meeting in Panama in November, it was noted that while CITES concerns the illegal international trade in species, what happens within a country’s domestic boundaries is none of its business.

Domestic trade will continue if profit remains a motive — until all the animals are just handbags, pretty chairs, face creams, fake medicines, caged lizards and cute slow lorises. Sub-standard permitting will make sure it’s all still possible.

Of COP27, the climate conference in Egypt last month, what can one say? More money was promised to the developing world for climate damage done by the excessive use of fossil fuels in the developed world. But of the absolutely essential reduction of fossil fuel use to keep the global temperature below 1.5°C, almost nothing useful was concluded.

Instead, Europe’s need for alternative gas supplies following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had African nations hoping to “dash for gas” by developing their own fossil fuel sectors.

It’s significant that more than 600 delegates at the conference were from the fossil fuel industry with a collective goal to perpetuate it.

For the past 50 years, the oil sector alone has been netting $3-billion a day. In 2021, the value of the coal industry was $571-billion. With those incomes and levels of production, plus teams of lobbyists ensuring they stay that high, the climate is essentially screwed.

COP15

Presently under way, as you read this, is the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15).

It has three official targets: the conservation of biodiversity, its sustainable use and the sharing of the benefits from the use of genetic resources.

It’s largely a for-human-use agenda, though part of it will be a push to protect 30% of land and sea by 2030.

It’s worth noting that COP14 in 2018 acknowledged that none of the targets adopted in 2010 had been achieved.

Then there are the costs. According to current financial estimates, to meet the funding gap for global biodiversity protection, existing investment needs to at least triple by 2030 and quadruple by 2050. Who’s going to pay? Frantic backpedalling and finger-pointing are inevitable.

Why the apathy?

So what’s really going on here? Why do so few people care about protecting nature? Why has this not changed in 60 years since the beginning of the conservation movement, especially given how much worse the situation is today, with a million species at risk of extinction?

According to Australian physicist Peter Lanius, writing in LynnJohnson News, this lack of caring is universal across all economic systems — capitalist, socialist or autocratic — and across all socioeconomic groups in developed and developing countries.

“In one crucial respect,” he writes, “they have always been going in the same direction since the advent of the industrial revolution. They favour economic growth and unchecked extraction of natural resources over any attempts to create balance and sustainability.”

We’re essentially predators and our prey is the wild environment, including fossil fuels. In this, there’s a rhythm which has been going on for millions of years. If prey is plentiful, there’s exponential growth in the predator population, leading to exhaustion of the “prey” and to collapse of the predator population.

We may claim, says Lanius, that our capacity for self-reflection and rational thought would enable us to behave differently. This evidently hasn’t happened yet. We are unusual, but still predators doing what predators do.

This is reinforced because we’re all born into a guiding ideology — a theology — with implicit assumptions we take for granted and never question, says Lanius. These get deeply embedded in social norms and become self-reinforcing. Every source of information in all social systems — education, books, music, TV, print, radio, film, online platforms, theatre) — are geared towards consumption as the ground floor of progress.

“We do not equate Earth/nature to a goddess that gives life,” he writes. “Instead, we talk about natural resources. Nature has no inherent meaning and hence no inherent value. It’s not divine, as in most earlier theologies.

“The result means that it’s perfectly ok for us, as humans, to make nature fit ‘our’ purpose. In fact, it puts no constraints at all on what we do with nature.”

Baked-in destructiveness

Destructive consumption, he says, is baked into our ideology about progress. Central to our laws and regulations is a lack of moral constraints in extracting from nature. Autocracies pursue the same economic growth paradigm as democracies, just with a bit more state control. Both keep investing in fossil fuels and the ongoing destruction of nature.

“Arguments between capitalists and socialists are about the distribution of the spoils, not about the morality of doing the spoiling,” he says.

This makes it extremely difficult to separate any concern we have about nature from immersion in systems in whose actions we are complicit and which give reason for that concern.

When a belief system is global, it takes great effort to create an opposing narrative that people find acceptable and are prepared to act on.

If we don’t manage to do that, however, our collective future is not assured. The problem is that most people don’t give a damn about this stuff.

It’s always someone else’s problem. Except it isn’t. It’s your and my and our children’s tomorrow. DM

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article ... ut-nature/