Threats to Vultures & Vulture Conservation

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5862

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 76117

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Threats to Vultures & Vulture Conservation

How conservationists’ wing tags are actually endangering the Cape vulture

14 March 2021 - 15:20

Philani Nombembe Journalist

A Cape vulture with a wing tag.

Image: VulPro

In a bid to save Cape vultures from extinction, conservationists fit them with wing tags. But a new study has found the tags are endangering the birds’ lives.

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behaviour in Germany and VulPro, a SA vulture conservation organisation, found that wing tags limit the movement and speed of vultures, compared with birds fitted with bands around their legs.

According to results published in the journal Animal Biotelemetry, conservationists have been fitting vultures with wing tags for over a decade.

The tags’ advantage is that they are large and “conspicuous enough for individuals to be identified from far away”. Smaller leg bands are “harder to notice and record the unique number”.

VulPro founder Kerri Wolter said: “After receiving many grounded and injured vultures from incorrect placement of wing tags, we felt there was an immediate need to find out exactly what these tags were doing to the flight of birds and whether this technique was, in fact, hindering the species rather than protecting them.”

Max Planck Institute researchers used GPS devices to track 27 Cape vultures

“marked with either patagial [wing] tags or leg bands”.

The GPS devices, which were mounted on the birds' backs, recorded the birds' positions as often as every minute for 24 hours a day, according to the study.

The recordings enabled the researchers to examine the birds' “flight performance, including occurrence of flight, proportion of time spent flying in a day, daily distance travelled and ground speed”.

Researchers observed that birds fitted with wing tags “covered a much smaller area in comparison to the leg band group”. They were less likely to take flight and, when doing so, flew at lower ground speed compared to individuals wearing leg bands.

“Though we did not measure the effects of patagial tags on body condition or survival, our results strongly suggest that patagial tags have severe adverse effects on vultures' flight performance,” said Max Planck research group leader Teja Curk.

The institute's Kamran Safi said vultures are scavengers, and by feeding on dead animals they play an important role in the ecosystem by preventing the spread of infectious diseases, recycling organic material into nutrients and stabilising food webs.

“Therefore, restricted flight potential and a reduction in the area covered by these birds, caused by improper tag attachment, can have far-reaching consequences at the ecosystem level,” he said.

TimesLIVE

https://www.sowetanlive.co.za/news/sout ... e-vulture/

14 March 2021 - 15:20

Philani Nombembe Journalist

A Cape vulture with a wing tag.

Image: VulPro

In a bid to save Cape vultures from extinction, conservationists fit them with wing tags. But a new study has found the tags are endangering the birds’ lives.

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behaviour in Germany and VulPro, a SA vulture conservation organisation, found that wing tags limit the movement and speed of vultures, compared with birds fitted with bands around their legs.

According to results published in the journal Animal Biotelemetry, conservationists have been fitting vultures with wing tags for over a decade.

The tags’ advantage is that they are large and “conspicuous enough for individuals to be identified from far away”. Smaller leg bands are “harder to notice and record the unique number”.

VulPro founder Kerri Wolter said: “After receiving many grounded and injured vultures from incorrect placement of wing tags, we felt there was an immediate need to find out exactly what these tags were doing to the flight of birds and whether this technique was, in fact, hindering the species rather than protecting them.”

Max Planck Institute researchers used GPS devices to track 27 Cape vultures

“marked with either patagial [wing] tags or leg bands”.

The GPS devices, which were mounted on the birds' backs, recorded the birds' positions as often as every minute for 24 hours a day, according to the study.

The recordings enabled the researchers to examine the birds' “flight performance, including occurrence of flight, proportion of time spent flying in a day, daily distance travelled and ground speed”.

Researchers observed that birds fitted with wing tags “covered a much smaller area in comparison to the leg band group”. They were less likely to take flight and, when doing so, flew at lower ground speed compared to individuals wearing leg bands.

“Though we did not measure the effects of patagial tags on body condition or survival, our results strongly suggest that patagial tags have severe adverse effects on vultures' flight performance,” said Max Planck research group leader Teja Curk.

The institute's Kamran Safi said vultures are scavengers, and by feeding on dead animals they play an important role in the ecosystem by preventing the spread of infectious diseases, recycling organic material into nutrients and stabilising food webs.

“Therefore, restricted flight potential and a reduction in the area covered by these birds, caused by improper tag attachment, can have far-reaching consequences at the ecosystem level,” he said.

TimesLIVE

https://www.sowetanlive.co.za/news/sout ... e-vulture/

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67596

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Threats to Vultures & Vulture Conservation

Better late than never! Strange that they have not thought about it before; those tags are very big

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67596

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Threats to Vultures & Vulture Conservation

Growing Demand for Vulture Heads Threatens the Birds’ Survival in Africa

BY MARÍA PAULA RUBIANO - 12TH APRIL 2021 - AUDUBON MAGAZINE

Across the continent, traditional healers are increasingly using the body parts of vultures, creating an illegal market that has experts alarmed.

Last year, at dawn on March 26, an exhausted Mohamed Henriques slid into his airplane seat. He had just managed to make it onto the last flight that left Guinea-Bissau before the small West African country closed its borders due to the coronavirus pandemic. Down below, amid the rest of the passengers’ luggage, sat the sole reason for his trip: a Styrofoam box filled with the corpses of three Hooded Vultures.

The days leading up to the flight had been a relentless race against the clock. As an internationally protected species, Hooded Vultures require transportation permits that usually take months to acquire. Henriques had a couple of weeks. And though the birds had arrived from the crime scene eight days before his flight, a pandemic curfew and ongoing political turmoil within the country further complicated the process. Eventually, with only seven hours left, Henriques managed to obtain the permits. But it wasn’t until the wheels of the plane were tucked into the aircraft’s belly did the ecologistbegin to feel a sense of relief. Once safely back at his lab at University of Lisbon, in Portugal, where he was working on his PhD, he could finally find out what exactly had killed the birds.

Along with a hundred others, the vultures had been found dead near the city of Bafatá, located in eastern Guinea-Bissau. Henriques, who was in the country at the time doing fieldwork for his thesis on migratory shorebirds in the Bijagós Islands, had heard that people in the eastern part of the country had witnessed at least 50 vultures drop dead from the sky. “And then, the day after, we heard on the radio that people found 100 more birds,” he says. In the following days Henriques started hearing of even more dead vultures in the same region. “That’s when it got really confusing.”

To discover what was behind the deaths, Henriques joined a team of five people from various African conservation organizations and veterinary services on a mission to one of the mass die-off areas near the city of Gabú. When they arrived, the group found hundreds of birds with their wings bent to the sides—a clear sign of the contortions poisoned raptors go through before dying. Disturbingly, many had also been decapitated, and in some cases the team found freshly dead vultures with their heads recently removed. “Surely someone knew they were going to die,” Henriques says.

While he was in the field, new reports of deaths kept popping up, and over the course of three weeks around 2,000 vultures—all but one of them Hooded Vultures—were found dead in six locations throughout eastern Guinea-Bissau. “Without a doubt, this is the biggest single incident of mass mortality of vultures we have ever recorded anywhere in the world,” says André Bothá, co-chair of the Vulture Specialist Group for the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Even more troublesome was that one of every four corpses had been missing its head.

A poisoned Hooded Vulture in Gabú, Guinea-Bissau around March, 2020. Photo: Mohamed Henriques

After interviewing local environmental authorities, livestock herders, and residents in areas where the birds had been found, the field team discovered that three men from Senegal had convinced locals to place poisoned pieces of meat as bait in exchange for payment. The toxicology analysis from the three dead vultures that Henriques took back to Portugal confirmed that the birds had died from consuming methiocarb, a pesticide commonly used in agriculture and easy to find in any market. “We have enough evidence to believe this was a coordinated thing,” he says.

Now, a year after the crime, many questions remain unanswered. The police investigation stalled after the only suspect fled the country. Travel restrictions due to the pandemic made it impossible to track him beyond Guinea-Bissau’s borders, says Henriques. The pandemic and ongoing political instability also distracted from the incident and paralyzed institutions that might have been able to find an answer. Meanwhile, in the past year, almost 1,200 vultures have been found dead across the continent, and 200 of them were beheaded Hooded Vultures in West Africa, according to the African Wildlife Poisoning Database.

“This poisoning continues to kill vultures in Africa,” Henriques says. “Things on the ground have sadly not changed.”

Darcy Ogada, an ecologist at The Peregrine Fund, has been warning about the decline of African vulture populations for almost a decade. According to an alarming 2015 report led by Ogada, the population of eight vulture species on the continent has declined 80 percent in only 10 years. The report called for action to protect the 11 vulture species in Africa that are “collapsing toward extinction.” Since then, 7 of those 11 vulture species are now considered critically endangered. “The areas where things were really bad in 2015 have pretty much remained the same,” Ogada says.

Poisoning—either intentional or accidental—is responsible for 90 percent of the vulture deaths, Ogada found in 2015. In some cases, to keep circling vultures from tipping off enforcement agencies, poachers of big mammals in South and Central Africa poison the birds. “Whenever they kill an elephant or a rhinoceros, a few meters away, they put some meat laced with poison, so that the vultures come down, eat the poison, and die immediately,” explains José Tavares, director of the Vulture Conservation Foundation. In other cases, when farmers poison large carnivores and mammals to prevent them from eating livestock or destroying crops, vultures become the unintended victims.

What happened in Guinea-Bissau, though, shows that the illegal killing and trade of vultures for their body parts is an increasingly worrisome threat, Ogada says. In most of West and South Africa, vulture heads are regarded by many as a good luck charm, similar to a rabbit’s foot in Europe or North America. Various vulture body parts are also used for traditional medicinal purposes. There’s evidence that more than a dozen ethnic groups use vulture heads, feet, and blood as treatments for a range of illnesses, as spiritual protection, or to gain the gift of looking into the future. According to a 2016 study, poisoning for such uses was behind 29 percent of the recorded vulture deaths in 26 West and Central African countries.

Hooded Vultures flock in Guinea-Bissau. Photo: Ana Coelho

Species like the White-backed Vulture or Rüppell’s Vulture are the most desired by traditional healers, leading to both birds’ populations being decimated and leaving both species critically endangered. Because of their scarcity now, poachers seem to be sourcing parts from countries where the populations of other species, like Hooded Vultures, have remained somewhat healthy, Ogada explains. Guinea-Bissau is one of those places. With roughly 43,000 Hooded Vultures, the country has the healthiest population in all West Africa, according to a survey Henriques conducted in 2017.

The pandemic has only exacerbated the problem, making an already lucrative business more alluring,

The use of vulture heads is a relatively new practice in Guinea-Bissau, which could partially explain its strong Hooded Vulture population, says Henriques. For this reason, experts don’t believe there’s enough internal demand in the country for all the missing heads from last year’s mass killing. Most likely, the body parts ended up in the stands of traditional healers in the bigger markets of Senegal or Nigeria, says Samuel Bakari, a vulture specialist for Africa at Birdlife International.

The pandemic has only exacerbated the problem, making an already lucrative business more alluring, says Stephen Awoyemi, conservation biologist at Central European University. Awoyemi has spent the past 10 years investigating the illegal trade of vulture body parts in Nigerian markets. Due to the travel restrictions to control the spread of the COVID-19 virus, prices have skyrocketed. Before the pandemic, a vulture head ranged between $10-$25, a dead bird went for $42, and a live vulture could cost up to $140 in Nigerian markets. Now, a head’s price can reach $39, a whole carcass is $92, and a live bird costs up to $210. As long as prices keep rising, the illegal trade will remain extremely attractive for many, says Awoyemi. “Just like in every profession, if you excel, you can become rich in a matter of years.”

In 2017, 128 African, European, and Asian countries signed the first plan to tackle the mass mortality of vultures across the three continents. According to the Multi-species Action Plan to Conserve African-Eurasian Vultures, through 2029, all participating states have to implement 124 conservation actions, such as promoting poison-free alternatives to mitigate human-wildlife conflict, introducing and enforcing strict penalties for illegal wildlife poisoning, and establishing an international, coordinated funding strategy. But according to Chris Bowden, one of the plan’s original architects who works for the Royal Society to Protect Birds, the program hasn’t spurred the actions or commitment necessary to make a meaningful dent in the killings or the demand behind them. “I don’t think it’s added as much relative to what was already happening,” he says.

Curbing the vulture trade is particularly difficult in West African countries, says Ogada. There, the legal system historically hasn’t been as aggressive about prosecuting wildlife crimes as it has been in African countries where big mammals still roam. That’s why in several West African countries conservationists have focused on training police officers and authorities on collecting evidence that could be used in court, border patrol officers on identifying the critically endangered species, lawyers on prosecuting wildlife cases, and judges on understanding the gravity of the crimes. But this is a long process, and in the meantime, says Ogada, it’s key to engage with those who create the demand in the first place.

One attempt at this strategy started in 2019, when Birdlife International partnered up with the Nigerian Conservation Foundation and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on the first project working directly with traditional healers from Nigeria, the country with the highest demand for vulture heads. The team has been working with 80 Nigerian traditional healers, trying to untangle trade networks and identify botanical alternatives used to treat illnesses supposedly cured by the vulture heads.

More than 100 White-backed Vultures and Hooded Vultures, both critically endangered, were poisoned in Mbashene, Mozambique in February of 2018. The birds were killed after feeding on a poisoned elephant carcass that was poached for its tusks. Photo: Andre Botha

The way leaders of the traditional healers’ organizations [in Nigeria]pass this knowledge is very organized,” Bakari explains. “They train other people and, through the project, we are trying to influence what they train. We want them to practice their tradition without having negative impacts on their biodiversity.”

But replicating the project in other countries might be tricky, says Bakari. In Nigeria, healers belonging to the Nigerian Traditional Healers Association don’t mind talking openly about their practices. In other countries, like Guinea-Bissau, the identity of a village’s healer is an open secret within the community, but the healer will not publicly admit that he plays that role. That doesn’t deter Henriques, though. “I think it’s a very interesting approach, and we should try it,” he says.

Yet others are skeptical that this strategy will even work in Nigeria. During his decade-long research in Nigerian markets, most buyers have told Awoyemi that they would never consider buying a vegetal alternative to a vulture body part. The birds’ powerful eyesight and the fact that they can feed on anything—including human beings—gives them unique healing powers, according to religious beliefs. In the Yoruba primordial myth, a vulture flew to Olodumare, in heaven, carrying a sacrifice to the gods over its head so that the Earth could be saved. “In that case, telling a Yoruba healer to use a plant instead of a vulture’s head is not gonna cut it,” Awoyemi says.

__________

The birds’ powerful eyesight and the fact that they can feed on anything gives them unique healing powers, according to religious beliefs.

__________

Rather, he believes introducing vulture conservation into peoples’ value system is more effective than trying to challenge or change those beliefs. As the president of the Religion and Conservation Biology Working Group at the Society for Conservation Biology in 2015, Awoyemi noticed that most traders selling vulture body parts in Nigerian markets are Muslims. Just as public health authorities have worked with religious groups to prevent HIV/AIDS in several African countries, Awoyemi wants to work with religious leaders in Nigeria to find passages in their scriptures that will inspire people to take up vulture conservation.

In the meantime, in Guinea-Bissau, Henriques is taking another approach, which includes education campaigns for the public and local environmental authorities. Through radio and TV appearances, he is trying to spread the message that the risk of a public health crisis increases without Hooded Vultures and their sophisticated digestive systems, which degrade tons of rotten meat and feces in urban settlements. Soon Henriques and his team will start meeting with stakeholders all over the country to make them aware of how important these animals are for humans.

Ultimately, greater awareness among local residents and internationally could be the most powerful force to save these birds, says Ogada. Since the killings in Guinea-Bissau, some progress has been made on the international front: The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora recognized the belief-based use of vulture body parts as a priority threat for the birds, and created the first working group on West African Vultures. Its members are now working on a special report about the illegal trade that they hope will be introduced during the next UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties in Glasgow, Scotland. Through the report, they want to pressure African countries to adopt a regulation that will effectively tackle the issue.

When people talk about illegal wildlife trade in Africa, they think of elephants, rhinos, right?” Ogada says. “Nobody thinks of birds. But I think it’s time.”

Original article: https://www.audubon.org/news/growing-de ... val-africa

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67596

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Threats to Vultures & Vulture Conservation

They cannot teach people to grow vultures in their backgarden

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 76117

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Threats to Vultures & Vulture Conservation

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67596

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Threats to Vultures & Vulture Conservation

SCIENCE SNIPPETS:

VULTURE CONSERVATION BENEFITS MORE THAN JUST VULTURES

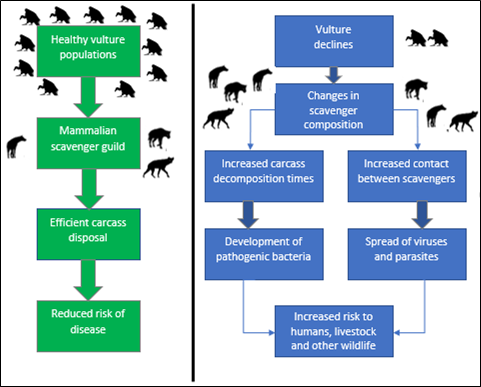

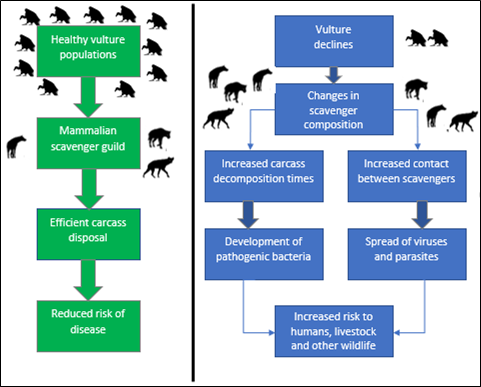

Vultures are an important component of an effective scavenger guild and have evolved a number of adaptations that allow them to locate and dispose of carcasses quickly and efficiently. (Guilds are groups of species that exploit the same resources.) A recent paper, co-authored by EWT staff*, discusses the ecosystem services provided by vultures and the consequences of the continuing decline of African vultures.

African vultures have evolved several specialisations to deal with their diet and any harmful pathogens that may be present in the carcasses they feed on. They thus play an important role in cleaning up carcasses that could cause disease in other animals, which could then be passed on to humans. The decline of African Vultures threatens the stability of the African scavenger guild, which may result in increased carcass decomposition times and, thus, the more rapid development and spread of harmful bacteria. Their absence may also result in changes in the composition of the vertebrate scavenger guild, with an increase in mammalian scavengers, which may increase the risk of viral disease transmission to humans, livestock, and other wildlife.

The economic value of vultures in terms of the sanitation or clean-up services that they provide has been evaluated for some species or countries outside of Africa (e.g., US$700 million per year for Turkey Vultures). Although they can only be deduced for Africa, they must also be substantial. For example, in East and West Africa, vultures consume up to 100 000 kg of organic waste annually, which aids local communities as they would otherwise have to pay for these services. Although the contribution of vultures to the economics of human health and veterinary care has not yet been quantified in Africa either, efforts to conserve vultures should not be deterred. Rabies is an important example of where the loss of vultures has led to substantial human health costs. 95% of global rabies cases occur in Africa and southeast Asia. In India, human health costs due to the loss of vultures were estimated at US$1.5 billion per year (Ogada et al. 2012) due to the increase in feral dogs and rabies.

The authors concluded that:

Vultures play a key role in the maintenance of ecosystem health. However, the implications of the decline of African vultures are not yet fully understood and require urgent investigation. Nevertheless, there is enough anecdotal and circumstantial evidence to warrant their urgent protection. It is estimated that the ecological and human health benefits provided by vultures far outweighs the cost of their conservation. The restoration of vulture populations and the ecosystem services they provide will benefit the welfare of all humans, but particularly those who are most vulnerable to economic instability and the spill over of disease at the human-wildlife-livestock interface.

*van den Heever L, LJ. Thompson, WW. Bowerman, H Smit-Robinson, LJ Shaffer, RM Harrell and MA Ottinger. 2021. Reviewing the Role of Vultures at the Human-Wildlife–Livestock Disease Interface: An African Perspective. Journal of Raptor Research. https://doi.org/10.3356/JRR-20-22

VULTURE CONSERVATION BENEFITS MORE THAN JUST VULTURES

Vultures are an important component of an effective scavenger guild and have evolved a number of adaptations that allow them to locate and dispose of carcasses quickly and efficiently. (Guilds are groups of species that exploit the same resources.) A recent paper, co-authored by EWT staff*, discusses the ecosystem services provided by vultures and the consequences of the continuing decline of African vultures.

African vultures have evolved several specialisations to deal with their diet and any harmful pathogens that may be present in the carcasses they feed on. They thus play an important role in cleaning up carcasses that could cause disease in other animals, which could then be passed on to humans. The decline of African Vultures threatens the stability of the African scavenger guild, which may result in increased carcass decomposition times and, thus, the more rapid development and spread of harmful bacteria. Their absence may also result in changes in the composition of the vertebrate scavenger guild, with an increase in mammalian scavengers, which may increase the risk of viral disease transmission to humans, livestock, and other wildlife.

The economic value of vultures in terms of the sanitation or clean-up services that they provide has been evaluated for some species or countries outside of Africa (e.g., US$700 million per year for Turkey Vultures). Although they can only be deduced for Africa, they must also be substantial. For example, in East and West Africa, vultures consume up to 100 000 kg of organic waste annually, which aids local communities as they would otherwise have to pay for these services. Although the contribution of vultures to the economics of human health and veterinary care has not yet been quantified in Africa either, efforts to conserve vultures should not be deterred. Rabies is an important example of where the loss of vultures has led to substantial human health costs. 95% of global rabies cases occur in Africa and southeast Asia. In India, human health costs due to the loss of vultures were estimated at US$1.5 billion per year (Ogada et al. 2012) due to the increase in feral dogs and rabies.

The authors concluded that:

Vultures play a key role in the maintenance of ecosystem health. However, the implications of the decline of African vultures are not yet fully understood and require urgent investigation. Nevertheless, there is enough anecdotal and circumstantial evidence to warrant their urgent protection. It is estimated that the ecological and human health benefits provided by vultures far outweighs the cost of their conservation. The restoration of vulture populations and the ecosystem services they provide will benefit the welfare of all humans, but particularly those who are most vulnerable to economic instability and the spill over of disease at the human-wildlife-livestock interface.

*van den Heever L, LJ. Thompson, WW. Bowerman, H Smit-Robinson, LJ Shaffer, RM Harrell and MA Ottinger. 2021. Reviewing the Role of Vultures at the Human-Wildlife–Livestock Disease Interface: An African Perspective. Journal of Raptor Research. https://doi.org/10.3356/JRR-20-22

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67596

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Threats to Vultures & Vulture Conservation

Poaching the scavengers: The use of vultures for muti has brought at least one species close to extinction

By Shaun Smillie• 25 August 2021

Two white-backed vultures perch in a leadwood tree at Kruger National Park. (Photo: Wikimedia)

Traditional healers are notoriously secretive, but researcher Mbali Mashele, with the help of an NGO, the Kukula Traditional Health Practitioners Association, was able to get some of its members to open up about the illegal use of endangered vultures.

In the northeastern corner of South Africa, between 400 and 800 vultures are believed to be killed each year for muti — and a source for these birds is the Kruger National Park.

This alarming figure emerged from a first-of-its-kind study that delved into the practices of traditional healers living in the Bushbuckridge area of Mpumalanga.

Some traditional healers admitted to using vultures for medicine, and on average were buying between one and two of these raptors a year.

Traditional healers are notoriously secretive, but researcher Mbali Mashele, with the help of an NGO, the Kukula Traditional Health Practitioners Association, was able to get some of its members to open up about their illegal use of these endangered birds.

The study used a questionnaire and 51 traditional healers living in the Bushbuckridge area were interviewed.

“Most of the vultures are harvested within protected areas like Kruger National Park, where they [poachers] go in illegally,” says Mashele, who was the lead author in the study that appeared in the Journal of Raptor Research.

Most of the traditional healers who admitted to using vultures said they didn’t know where the birds were poached. This is because poachers killed the birds and sold the carcasses to them.

Of those who did know, 16% said the birds they obtained had come from Kruger National Park.

Vultures were also sourced from communal rangelands and other protected areas like Manyeleti, Sabi Sands and Bushbuckridge nature reserves.

Acquiring the raptors, the questionnaire found, usually involved poisoning or trapping. Poisoning is decimating vulture populations across Africa.

In June 2019, 537 vultures were found dead in Botswana after feeding on three poisoned elephant carcasses.

And it is not just poaching: vultures are facing other threats.

“There is simply a bundle of things against them across Africa,” explains Prof Colleen Downs of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, who was an author of the study.

“In some of the areas, people simply don’t realise that they provide ecosystem services by removing dead carcasses.”

Power lines are killing vultures and in some areas their decline is also being caused by an unlikely culprit — the elephant.

“Some of the vultures use trees near rivers to nest in and elephants have been pushing them over,” says Downs.

Most of the traditional healers in the study admitted to using between one and two vultures a year, although one individual said he bought on average eight to 10 a year.

From these figures, the researchers estimated that members of the Kukula Traditional Health Practitioners Association using vulture muti were acquiring between 400 and 800 birds a year.

This figure, the authors point out in the paper, is not sustainable for the vulture population in the area.

The study also revealed what ailments the vultures were being used to supposedly treat. The birds were either provided to the healers whole or powdered.

Sometimes they are used to cure headaches, while the liver is believed to provide good dreams.

“The brain and the head are the most important part,” explains Mashele.

The eyes supposedly provide the ability to see into the future while the brain brings good fortune.

During periods of hardship, it is found that more people are willing to take the risk and poach vultures themselves.

The price for a vulture, Mashele found, fluctuates depending on economic circumstances. Prices also varied according to the species of vulture, as some of these raptors are believed to have more potent powers than others.

The most valued species, the study found, is the Cape vulture, which could sell for as much as R1,500. A white-backed vulture, common in the area, sells for between R300 and R1,000.

Interestingly, among some traditional healers, the study found that there was a reluctance to use vultures that had been poisoned. Many will carefully examine the carcass looking for signs of poisoning. The reason for this is a concern that the poison could affect the health of the user.

It is not known if there have been instances where people have been poisoned from vulture muti, and Mashele believes it would be difficult to assess.

“The thing is, if you drop dead in the village, there is not going to be a post-mortem… they are going to say you died of natural causes. We need to look at that in the future.”

As Mashele stresses, the majority of traditional healers in the area are against using vultures for muti. She says the Kukula Traditional Health Practitioners Association is a non-profit organisation that encourages conservation practices, and that it is possible to change beliefs.

“There are a couple of funding proposals we have applied for, to implement vulture protection areas. We also want to link up with communities to say that you have a role in protecting these species,” says Mashele.

But the concern is that time is running out for the vulture, as some species are already facing local extinction within the borders of South Africa.

“They are in dire straits. There was a really good paper done in 2012 by one of the guys who worked at KZN Wildlife. They predicted that in 10 years, the white-backed vulture would become extinct in the wild in Kwazulu-Natal. Now, 10 years later, it has almost happened. There are very few nests left in the wild,” says Downs. DM/OBP

By Shaun Smillie• 25 August 2021

Two white-backed vultures perch in a leadwood tree at Kruger National Park. (Photo: Wikimedia)

Traditional healers are notoriously secretive, but researcher Mbali Mashele, with the help of an NGO, the Kukula Traditional Health Practitioners Association, was able to get some of its members to open up about the illegal use of endangered vultures.

In the northeastern corner of South Africa, between 400 and 800 vultures are believed to be killed each year for muti — and a source for these birds is the Kruger National Park.

This alarming figure emerged from a first-of-its-kind study that delved into the practices of traditional healers living in the Bushbuckridge area of Mpumalanga.

Some traditional healers admitted to using vultures for medicine, and on average were buying between one and two of these raptors a year.

Traditional healers are notoriously secretive, but researcher Mbali Mashele, with the help of an NGO, the Kukula Traditional Health Practitioners Association, was able to get some of its members to open up about their illegal use of these endangered birds.

The study used a questionnaire and 51 traditional healers living in the Bushbuckridge area were interviewed.

“Most of the vultures are harvested within protected areas like Kruger National Park, where they [poachers] go in illegally,” says Mashele, who was the lead author in the study that appeared in the Journal of Raptor Research.

Most of the traditional healers who admitted to using vultures said they didn’t know where the birds were poached. This is because poachers killed the birds and sold the carcasses to them.

Of those who did know, 16% said the birds they obtained had come from Kruger National Park.

Vultures were also sourced from communal rangelands and other protected areas like Manyeleti, Sabi Sands and Bushbuckridge nature reserves.

Acquiring the raptors, the questionnaire found, usually involved poisoning or trapping. Poisoning is decimating vulture populations across Africa.

In June 2019, 537 vultures were found dead in Botswana after feeding on three poisoned elephant carcasses.

And it is not just poaching: vultures are facing other threats.

“There is simply a bundle of things against them across Africa,” explains Prof Colleen Downs of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, who was an author of the study.

“In some of the areas, people simply don’t realise that they provide ecosystem services by removing dead carcasses.”

Power lines are killing vultures and in some areas their decline is also being caused by an unlikely culprit — the elephant.

“Some of the vultures use trees near rivers to nest in and elephants have been pushing them over,” says Downs.

Most of the traditional healers in the study admitted to using between one and two vultures a year, although one individual said he bought on average eight to 10 a year.

From these figures, the researchers estimated that members of the Kukula Traditional Health Practitioners Association using vulture muti were acquiring between 400 and 800 birds a year.

This figure, the authors point out in the paper, is not sustainable for the vulture population in the area.

The study also revealed what ailments the vultures were being used to supposedly treat. The birds were either provided to the healers whole or powdered.

Sometimes they are used to cure headaches, while the liver is believed to provide good dreams.

“The brain and the head are the most important part,” explains Mashele.

The eyes supposedly provide the ability to see into the future while the brain brings good fortune.

During periods of hardship, it is found that more people are willing to take the risk and poach vultures themselves.

The price for a vulture, Mashele found, fluctuates depending on economic circumstances. Prices also varied according to the species of vulture, as some of these raptors are believed to have more potent powers than others.

The most valued species, the study found, is the Cape vulture, which could sell for as much as R1,500. A white-backed vulture, common in the area, sells for between R300 and R1,000.

Interestingly, among some traditional healers, the study found that there was a reluctance to use vultures that had been poisoned. Many will carefully examine the carcass looking for signs of poisoning. The reason for this is a concern that the poison could affect the health of the user.

It is not known if there have been instances where people have been poisoned from vulture muti, and Mashele believes it would be difficult to assess.

“The thing is, if you drop dead in the village, there is not going to be a post-mortem… they are going to say you died of natural causes. We need to look at that in the future.”

As Mashele stresses, the majority of traditional healers in the area are against using vultures for muti. She says the Kukula Traditional Health Practitioners Association is a non-profit organisation that encourages conservation practices, and that it is possible to change beliefs.

“There are a couple of funding proposals we have applied for, to implement vulture protection areas. We also want to link up with communities to say that you have a role in protecting these species,” says Mashele.

But the concern is that time is running out for the vulture, as some species are already facing local extinction within the borders of South Africa.

“They are in dire straits. There was a really good paper done in 2012 by one of the guys who worked at KZN Wildlife. They predicted that in 10 years, the white-backed vulture would become extinct in the wild in Kwazulu-Natal. Now, 10 years later, it has almost happened. There are very few nests left in the wild,” says Downs. DM/OBP

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 76117

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Threats to Vultures & Vulture Conservation

How primitive!

And note that elephant are pushing their nests over!

And note that elephant are pushing their nests over!

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67596

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Threats to Vultures & Vulture Conservation

The trees that the elephants push over are the least, what about getting rid of the traditional healers?

A medical doctor needs a university degree in order to be allowed to cure people and the traditional healers.....?

A medical doctor needs a university degree in order to be allowed to cure people and the traditional healers.....?

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge