Published: September 14, 2022 4.51pm BST by Alena Pance, Senior Lecturer, Molecular Genetics, University of Hertfordshire

A vaccine candidate, called R21, has been shown to be up to 80% effective at preventing malaria in young children, according to the latest trial results.

This follows from a study published in 2021 from the same team at Oxford University which showed that the three-dose vaccine was up to 77% effective at preventing malaria. Their latest study shows that a booster, given a year later, maintains the levels of protection at 70% to 80%, suggesting that long-term protection is possible.

The Oxford researchers told the BBC that their vaccine can be made for “a few dollars”, and they have a deal to manufacture over 100 million doses a year.

However, there is still a large hurdle to overcome. Phase 3 clinical trials – the final phase of testing in humans before regulatory approval can be sought – are yet to be conducted.

A long road with many dead ends

The quest to develop a malaria vaccine began almost 100 years ago. As early as the 1940s, attempts to protect against malaria infection by injecting inactivated parasites were conducted in animals and in humans. Since then, relentless efforts continued until advances in biochemistry and molecular biology made it possible for scientists to isolate proteins from the plasmodium parasite that causes malaria to use in the vaccine and make them in a lab.

These proteins were predicted to induce better immunity against infection. Although the parasite has the same proteins, their accessibility and exposure to the immune system can be less effective at inducing a response. Also, using inactivated whole parasites bring other potential problems, such as toxicity and even the re-activation of the parasite causing an active infection.

These modern techniques led to the development in the late 1980s of the SPf66 vaccine that comprised several synthetic molecules of the parasite that were known to be recognised by the immune system in humans. The vaccine, which was developed in Colombia, was trialled in various countries in South America, achieving an efficacy of 35% to 60%. But when testing was extended to other continents, efficacy was lower: 8% to 30% in Africa and no protection at all in Asia.

Though disappointing, these findings were encouraging because some immunity was achieved, showing that a vaccine against the biggest killer in the tropical world is possible.

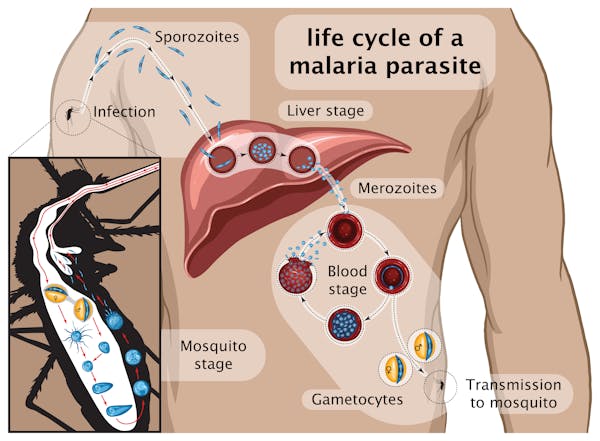

Many vaccines were designed since using different components of the parasite and tested in clinical trials, including RTS,S which became the first licensed anti-malaria vaccine. It contains part of a major protein found on the surface of the parasite that starts the infection: the so-called sporozoite stage (see graphic below) that infects the liver.

Stages of malaria. N.Vinoth Narasingam/Shutterstock

RTS,S was widely tested in Africa, reaching levels of protection of around 40% that decreased with time. It is based on the same parasite molecule used in R21.

Achieving high levels of protection against malaria has proven very difficult. Even in those cases when promising results were obtained, the effectiveness decreased dramatically when testing the vaccines more widely.

Another issue is that, very often, immunity gained from these candidate vaccines fell over time. Long-term immunity is important because the risk of infection continues throughout life, particularly in areas where transmission is high.

Why it’s been so hard to find an effective vaccine

Advances in gene sequencing in the past few decades have allowed us to analyse the malaria-causing parasite’s genome.

The sequencing of samples from patients from around the world changed our understanding of the parasite and the disease. It became clear that there isn’t one parasite but many genetically distinct strains. And this diversity is reflected in the components of the parasite, including those used in the vaccines.

Because the vaccines were developed with strains of parasites kept in laboratories, the identity of the vaccine is restricted to that particular parasite and, as a result, the immune system will be trained to recognise similar parasites but not necessarily other genetically different strains. This problem is increased by the complexity of the life cycle of these parasites and the differences in the dynamics of the infection in different regions of the world.

In Africa, the transmission of the disease is high and, as a result, it is common that people get infected with several genetically different parasites. So if the vaccine is effective against limited genetic versions, then some will be eliminated by the immune system but not others. This is a major problem in developing an effective vaccine against malaria because it makes it difficult to eliminate the parasite from the body. This might also be at least part of the reason most vaccines tested so far have low protection which wanes over time.

The high level of protection obtained with R21, the malaria vaccine developed by scientists at Oxford University, is really promising. The protection it gives will be followed closely with great expectations to find out whether it can be sustained in the long term. It will also be very important to test it in different parts of the world to find out if it gives wide protection. And, finally, it will also be helpful to know whether it can protect older children and adults and become a general preventive tool against malaria.