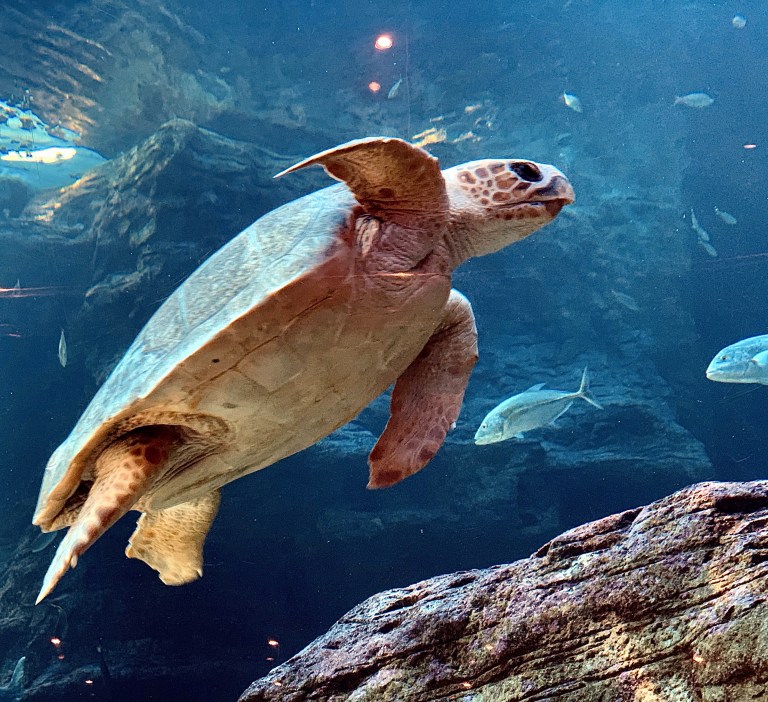

A bronze whaler shark found in Cove Rock in East London on 1 May 2022. (Photo: Kevin Cole)

By Tembile Sgqolana | 07 Jun 2022

Scientists are trying to find out what is causing the stranding of bronze whaler sharks on Eastern Cape shores between East London and Jeffrey’s Bay.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Scientists from the eastern and southern coasts of South Africa are working tirelessly to find out what caused the sudden stranding of close to 50 bronze whaler sharks between East London and Jeffrey’s Bay in less than three months.

The bronze whaler sharks are listed as near-threatened on the International Union for Conservation of Nature list as they are often targeted in commercial and recreational fishing for their meat.

Since late March this year, people have been reporting stranded bronze whaler sharks on the beaches of East London and Jeffrey’s Bay.

East London museum scientist Dr Kevin Cole, shark expert Dr Matt Dicken from the KwaZulu-Natal Sharks Board, Bayworld marine biologist Dr Greg Hofmeyr and Dr Malcolm Smale, a retired Bayworld scientist, have put their heads together to find out why the sharks are coming ashore.

Cole said from 30 March to date, the tally has climbed for the number of adult bronze whaler sharks reported stranded on beaches in the Eastern Cape (mostly between Jeffrey’s Bay and East London).

A pregnant bronze whaler shark with 11 pups in Winterstrand on 6 May 2022. (Photo: Kevin Cole)

“In the East London area alone, the museum has investigated five bronze whalers, four females (two were pregnant) and a male. They showed no signs of physical trauma or bite marks. Other reports which have come in include a stranding at Hamburg and two in Chintsa Bay (Rooiwal and Bosbokstrand). The high seas this week have taken the Chintsa Bay carcasses back out to sea and they could not be investigated,” he said.

Cole said both were fresh specimens when reported, as noted by the photographic evidence.

“A female bronze whaler investigated at Glengarriff on 7 April 2022 had 15 pups and the second pregnant female at Winterstrand on 6 May 2022 had 11 pups. To date, scientists have not been able to determine the cause of death and a number of potential threats have been ruled out such as recreational mortality,” he said.

He said sampling of fresh carcasses will be ongoing for pathology and toxicology investigations.

“Members of the public are requested to report any strandings to the authorities and are cautioned not to eat the meat for health reasons,” he said.

Hofmeyr said that since March this year, about 50 sharks had washed ashore around East London and Jeffrey’s Bay.

“In almost two-and-a-half months there have been almost 50 sharks of the same species that have come ashore. The reason for them to come ashore is still not clear and it is unprecedented,” he said.

Hofmeyr said the sharks were washed ashore either dead or uncoordinated.

“There is a question of whether these animals have been caught by commercial fishing vessels and released. The other question is why there are no other shark species washed ashore. The other option is that there might be a disease,” he said.

He said all the sharks seem to be adults with an equal number of females and males.

“When we opened them up their stomachs were empty. These are top predators and their population is very low. The current status of copper sharks in South African waters is not known and they have been evaluated as near-threatened on the IUCN Red List (2003),” said Hofmeyr.

He said they are responding wherever someone reports a shark ashore.

“We need the information on why these sharks are dying. The post-mortems of the sharks revealed that they suffered no injuries or any signs of physical injury. We urge the public to report any shark strandings to the Bayworld and East London Museums,” he said.

Another bronze whaler shark found in Gonubie on 27 April 2022. (Photo: Kevin Cole)

Stranded sharks should be reported to the regional base of the Stranding Hotline at 071 724 2122.

Our Burning Planet asked for a comment from Dicken and Smale, but they had not responded by the time of publishing.

In his response to the Eastern Cape’s Daily Dispatch, Dicken said bronze whaler sharks followed the sardine run — a seasonal migration of fish followed by predators feasting on the large school — from the Eastern Cape coastline to the south coast in KwaZulu-Natal.

“Another potential cause could be ingesting poisoned fish. Shellfish poisoning from red tide algae, when the sardines eat the toxic algae, the sharks could die from neurotoxic poisoning. Neurotoxic algae produce domoic acid which can cause weakness, confusion and disorientation. But experts have been saying there aren’t any signs of red algal blooms and other species who eat sardines would be affected,” said Dicken.

He said having spoken to bacteriologists, some people think it could be a bacterial infection which is why one species is more susceptible to wash-ups.

“The only way to confirm that is to do an autopsy on fresh shark carcasses and take samples to test the eco-toxin. Samples have been collected but not processed to date,” he said. DM/OBP