‘Loved to death’: Poaching for the horticultural market threatens cycads in South Africa

Cycads, considered as status symbols, at a private property in South Africa. The plant group is the most threatened in the world. (Photo: Daniel Stiles)

By Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime | 04 Jan 2022

Cycads, considered as status symbols, at a private property in South Africa. The plant group is the most threatened in the world. (Photo: Daniel Stiles)

By Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime | 04 Jan 2022

Cycads, an ancient group of plants dating from the time of the dinosaurs, are threatened globally by extinction. The plants are also coveted by collectors, especially rarer specimens. In South Africa, a hotspot of cycad diversity, this demand has given rise to a harmful illicit market that has placed dozens of species at risk. Thousands of cycads have been dug up from the wild, with poachers using a legal cycad market to launder their harvests.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, in Cape Town, South Africa, is globally famous for its displays of indigenous vegetation. One section of the garden is given over to cycads, a group of plants so ancient that dinosaurs once roamed among them. Cycads are greatly prized by collectors and rare specimens can sell for tens of thousands of dollars. This is why the most valuable cycad in Kirstenbosch is now secured inside a cage — to prevent poachers from digging it up.

This is not an imagined threat. Over two rainy nights in August 2014, poachers made off with 24 Encephalartos latifrons cycads from the gardens, collectively worth more than $65,000. That particular species of cycad is critically endangered, with fewer than 100 surviving plants in the wild. The incident received international attention, yet dozens like it take place each year. The illicit cycad trade in South Africa has grown so organised, lucrative and harmful that the authorities have identified it as a priority wildlife crime, alongside rhino, elephant and abalone poaching.

Home of rare cycads — and cycad poaching

South Africa is a hotspot of cycad diversity, hosting 38 species, or around a tenth of the world’s total. Of these species, 29 are endemic, found nowhere else on earth. Already, three of South Africa’s cycads are extinct in the wild, and half of the remaining species are at risk of extinction in the near future. In 2005, poachers dug up the last 11 survivors of one species on a mountain where, less than three decades earlier, more than 200 of the plants had been counted.

Cycad plants recovered from poachers. (Photo: SANParks)

Cycad plants recovered from poachers. (Photo: SANParks)

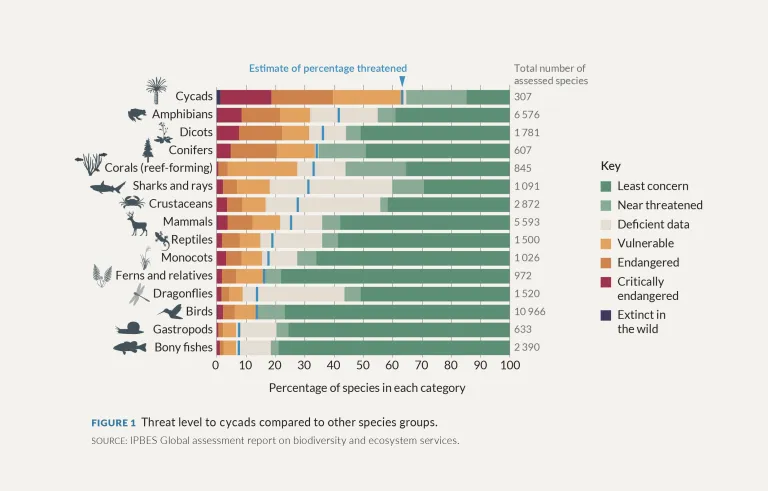

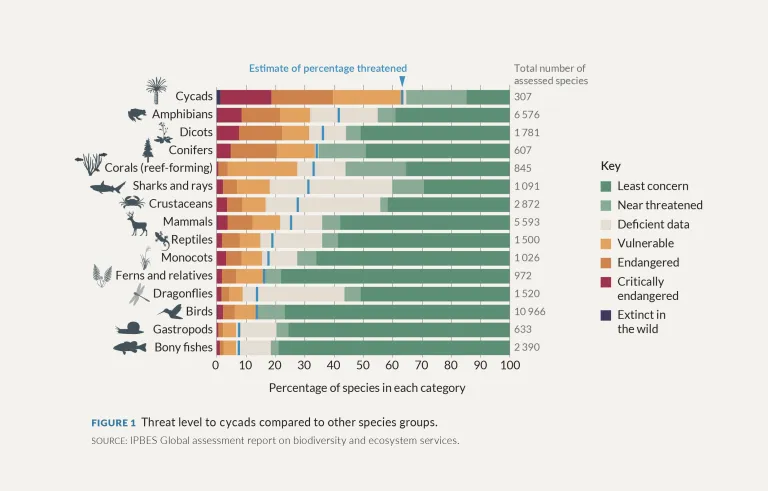

The costs are especially pronounced given the global conservation status of cycads, which have been described by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as the most threatened plant group in the world. Cycads flourished during the Jurassic period and were previously found around the world. Now, the spiny plants only occur in southern Africa, central America, South East Asia and Australasia. Individual plants can live 1,000 years or more because they continue to produce new offshoots at the base of the trunk.

The biggest threat to cycads in South Africa comes from people obsessed with owning them; as one recent magazine feature put it, cycads “are being loved to death”. Cycads are considered status symbols by wealthy collectors in South Africa and internationally: as one participant said to researchers studying the trade in South Africa, “owning a rare cycad displays wealth and intelligence in a way owning luxury cars does not”.

But the plants grow extremely slowly — around a centimetre per year — and take decades to reach maturity. Lacking patience, many collectors prefer to buy fully grown cycads, driving the illicit market. This illicit trade has operated for decades in South Africa, but may have intensified in recent years as the plants become rarer in the wild, and thus more coveted. Of more than 630 cycads confiscated by police in the Eastern Cape between 2011 and 2016, every single one was on the IUCN Red List, demonstrating a clear market preference for threatened species.

The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime’s monthly East and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin:

Cycads are also harvested illegally in South Africa for producing traditional medicine, or muthi. A 2014 study estimated that several tonnes of cycad bark are sold annually. People who trade illegally in live cycads have justified doing so by arguing that, if left in the wild, the plants would be harvested for medicine (or fall foul of ground clearance for development or agriculture). Yet the medicinal market is far smaller and less damaging to cycad populations than the horticultural trade.

Since the 1970s, it has been prohibited to harvest, trade or possess wild cycads in South Africa, but a legal market still exists for cultivated plants. This provides cover for traffickers and enables the laundering of poached cycads. Conservationists recently estimated that, in the South African city of Pretoria alone, there were as many as 36,000 households with cycads — many times more than officials can inspect. (This is compounded by the widespread securitisation of wealthier houses in South Africa, with many located within gated communities, making access even more difficult for inspectors.) “Many homes could have cycads purchased from traffickers and no one would know,” says John Donaldson, a cycad expert who formerly worked for the South African National Biodiversity Institute. Conservationists have reported visiting homes with ostensibly cultivated cycads that bore unmistakable traces of wild origins, such as burn marks from fires and bites from porcupines.

There are also international protections for South African cycads, but these, too, can be circumvented. All of South Africa’s cycad species are listed on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) Appendix I, which means, in theory, that plants obtained from the wild may not be exported. Yet informants in the horticultural industry say that traders continue to export cycads illegally, for example by mis-declaring the plants as palm trees, which superficially resemble cycads and are not protected under CITES. In a 2001 sting operation, dubbed Operation Botany, US authorities arrested six men for a scheme to traffic wild cycads worth an estimated $1.3-million from South Africa. The available evidence, however, points to South Africa’s domestic cycad market as a bigger threat than international trafficking.

The threat level to cycads compared with other species groups. (Source: IPBES Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services)

The Eastern Cape-Gauteng connection

The threat level to cycads compared with other species groups. (Source: IPBES Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services)

The Eastern Cape-Gauteng connection

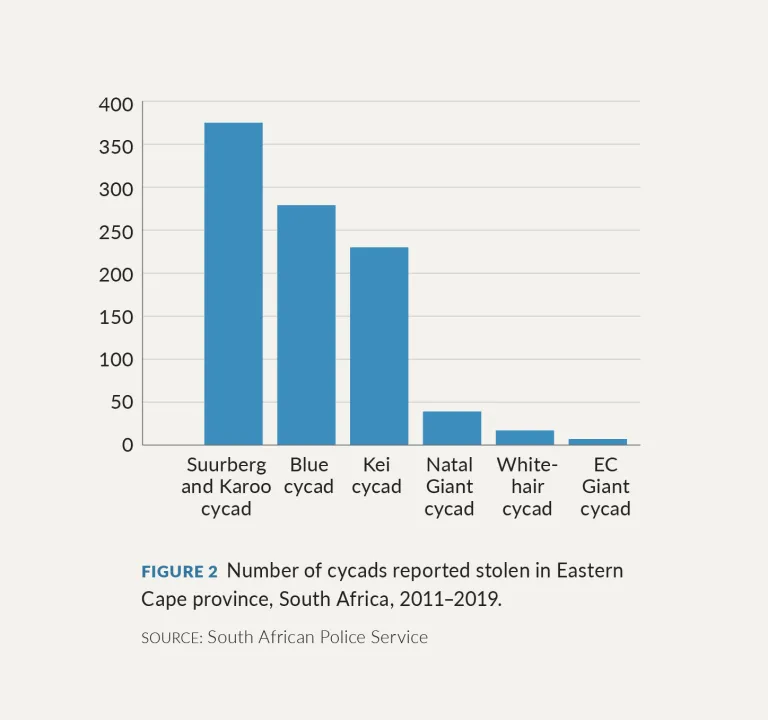

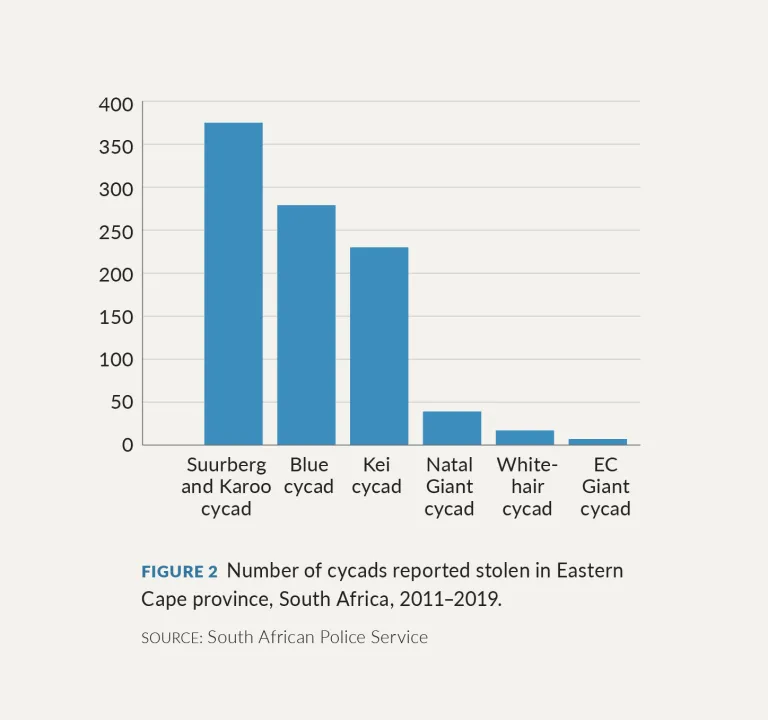

A major centre of South Africa’s cycad poaching crisis is the Eastern Cape province, home to 14 native cycad species. Research by retired high-ranking police official Brigadier General Andre Krause indicates that, between 2011 and 2018, close to 1,000 cycads were uprooted in 27 separate poaching incidents, with an estimated value of $1.2-million. Police in the small town of Jansenville alone (population 5,600) recorded more than 350 stolen cycads. And these are only poaching incidents that have been reported to the police.

Several cycad poachers have been arrested on multiple occasions, including a local farm owner. This suggests that cycad poaching is a specialised market, requiring specialist knowledge of which species are valuable, as well as access to buyers. The majority of offenders have residential addresses in and vehicle registration numbers from Gauteng, South Africa’s wealthiest and most populous province, supporting a conclusion that poached cycads are being transported across the country before being sold.

Krause said in an interview that “rich collectors” in Gauteng were behind the illicit trade. Interviews with incarcerated poachers by TRAFFIC, the wildlife-trade monitoring organisation, reveal a similar connection. One poacher described how poached cycads were “simply covered with plastic sheeting” and driven from the Eastern Cape to Gauteng. Research by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime found that cycad prices are typically higher at nurseries in Gauteng than elsewhere in South Africa.

Cycads are typically priced per centimetre, with rarer species considered more valuable; other factors that influence the cost of cycads include age and signs of damage. In general, poached cycads retail for around a quarter of the legal price, according to informants. This is because the plants are usually in poor condition after being crudely dug out using crowbars and pangas, and then transported without adequate care or maintenance. This provides buyers with opportunities to obtain cycads cheaply and is also said to provide incentives for corrupt nurseries to buy poached plants and launder them into licit markets.

The number of cycads reported stolen in the Eastern Cape, 2011–2019. (Source: South African Police Service)

The number of cycads reported stolen in the Eastern Cape, 2011–2019. (Source: South African Police Service)

Very little of this money reaches the people responsible for harvesting the plants. Some poachers have reported being hired on false pretences — “to cut down trees”, as one incarcerated poacher told TRAFFIC — and earning little more than $40 per job. More experienced poachers report higher earnings, and some go on to become so-called “recruiters”, hiring other people to chop down cycads. It appears that the trade operates via kinship networks, with police data from the Eastern Cape showing that a large number of arrested poachers are Zimbabwean nationals.

A robust illicit trade

The Covid-19 pandemic, which restricted passenger flights and interprovincial travel for more than six months in 2020, appears not to have had a major effect on the illicit cycad trade. Informants reported that there were no significant changes in cycad prices. Two cases of cycad theft from private residences were reported in the Eastern Cape during lockdown, while authorities in the neighbouring Western Cape noted a brief decline in cycad poaching, followed by a rapid escalation, with cycads worth approximately $1-million stolen in just six months of 2021.

Various attempts have been made to deter cycad poaching, including implanting microchips and a technique known as microdotting, or spraying the plants with minuscule dots, each of which has a scannable reference code unique to each plant. But both methods are time consuming, requiring individual plants to be tagged in the wild, and poachers have developed workarounds, such as X-raying plants and digging out the microchips. Researchers from the University of Cape Town have now developed a promising technique for identifying wild cycads using radiocarbon dating and stable isotopes, which act as hyper-local signatures of the landscape where individual cycads grew. These signatures are intrinsic to each plant and cannot be removed. The primary application of this method, however, is in detecting cycads that have already been poached, not preventing poaching in the first place.

For now, the surest method of keeping wild cycads in the ground appears to be physically enclosing them, an option available mainly to private landowners. Currently, on a wine farm in the Western Cape, engineers are discussing how to secure an exhibit of valuable cycads, due to fears they may be stolen. For the shrinking number of wild cycads in South Africa, though, there is no such protection. DM/OBP

This article appears in the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime’s monthly East and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin. The Global Initiative is a network of more than 500 experts on organised crime drawn from law enforcement, academia, conservation, technology, media, the private sector and development agencies. It publishes research and analysis on emerging criminal threats and works to develop innovative strategies to counter organised crime globally.

Female Cone

Female Cone Female Cone

Female Cone