African Penguin

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67563

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: African Penguin

The one lying on the back is my favourite

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67563

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: African Penguin

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5862

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

Re: African Penguin

Very interesting article this

https://www.capetownetc.com/cape-town/w ... came-from/?

Where the Cape's penguins came from

Published by Aimee Pace on January 16, 2020

The smartly dressed penguins us locals have come to know and love that call Boulders Beach and Stony Point home have not always been there and if you, like us, have been wondering where they came from, you’re in the right place.

Before 1985 these flightless bird colonies were nowhere to be seen. What many people don’t know is that penguins from time to time tend to resettle in new areas either in search of food or mates.

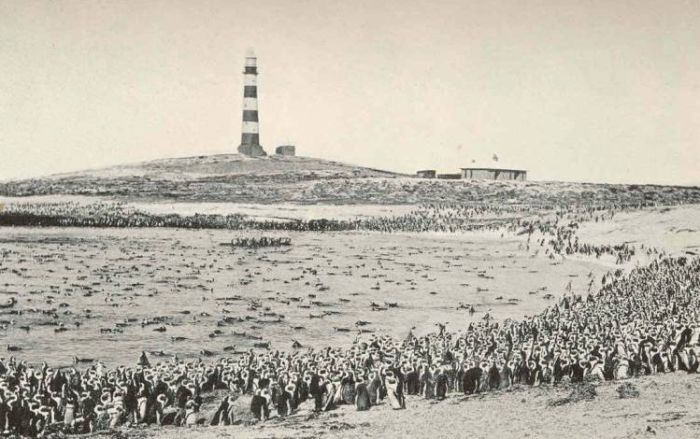

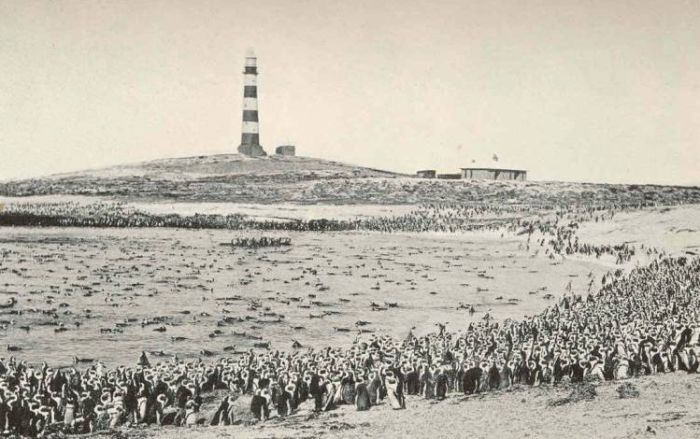

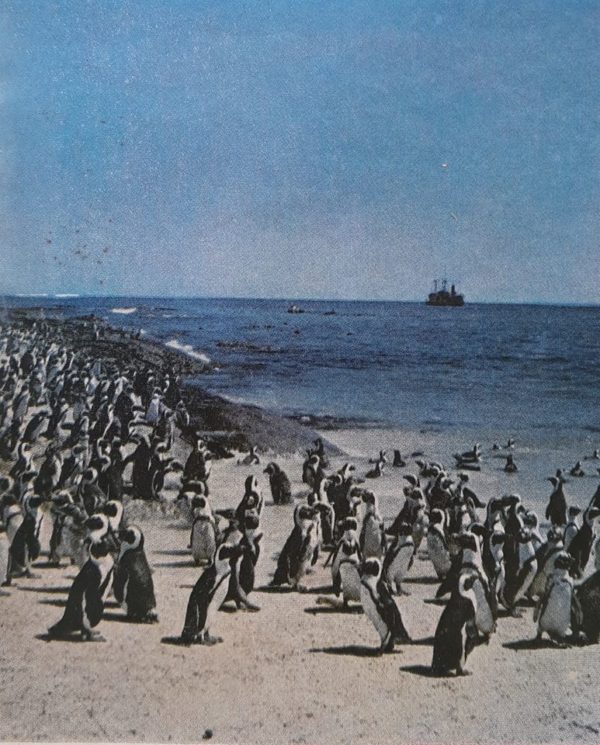

1962. Dassen Island, between Cape Town and Saldanha Bay.

Before 1985, the closest and most densely populated colony near to the Cape was Dassen Island, 9km off Yzerfontein. Here, thousands of cheerful African penguins called the peaceful island home until their numbers began to decline drastically in the 1960s and 70s when the anchovy stockpile in the area was affected by overfishing. Although Dassen Island housed the nearest colony, most African penguins came from Namibia.

Penguins were forced to abandon their nests in droves in the 1980s in search of food and a new habitat. This led to young penguins settling down and starting new colonies along Stony Point and Boulders Beach.

Whales being processed in the area.

Before Stony Point was a feather-filled tourist attraction it was one of the areas associated with whaling between the 19th and 20th centuries. In 1912, 60 hectares of land including Stony Point was leased to Captain Cook who established The Southern Cross Whaling Company Ltd, profiting from the horrors of whaling.

A whaling station was established in the area and roughly 173 whales were killed in the seas off Cape Hangklip in 1913 and 84 in 1914.

Between 1916 and 1920, 300 whales were killed each year by steam ships that operated from the Stony Point whaling station and 144 people were employed in the grim business.

In 1976 whaling was outlawed and the dark years were left behind when Cape Nature upgraded the area due to its historical significance and welcomed the penguin colony we know today.

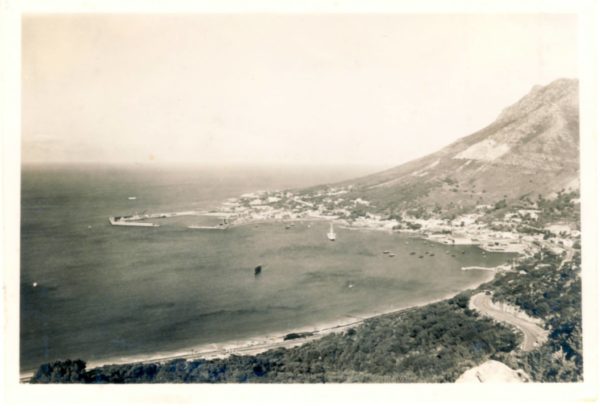

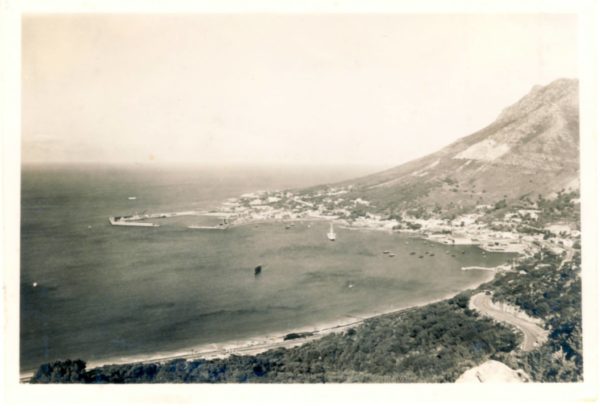

An old photo of Simon’s Town where Boulders Beach is located.

Unsurprisingly named after its giant granite boulders, this much-loved destination only welcomed penguins in 1983.

The colony has increased to over 3 000 strong but was started by just two breeding pairs spotted on Foxy Beach by locals roughly 37 years ago. The beach is enclosed, surrounded by boulders believed to be some 540-million years old.

Before, the beach was somewhat lonely without the little flightless birds to liven up the atmosphere, and now it is one of only two areas in Cape Town that the endangered African penguins call home.

Pictures: Cape Town Down Memory Lane/Michael Nicoll

Sources:

http://www.theheritageportal.co.za

https://www.simonstown.com/penguins

https://www.aquarium.co.za/blog/

https://www.capetownetc.com/cape-town/w ... came-from/?

Where the Cape's penguins came from

Published by Aimee Pace on January 16, 2020

The smartly dressed penguins us locals have come to know and love that call Boulders Beach and Stony Point home have not always been there and if you, like us, have been wondering where they came from, you’re in the right place.

Before 1985 these flightless bird colonies were nowhere to be seen. What many people don’t know is that penguins from time to time tend to resettle in new areas either in search of food or mates.

1962. Dassen Island, between Cape Town and Saldanha Bay.

Before 1985, the closest and most densely populated colony near to the Cape was Dassen Island, 9km off Yzerfontein. Here, thousands of cheerful African penguins called the peaceful island home until their numbers began to decline drastically in the 1960s and 70s when the anchovy stockpile in the area was affected by overfishing. Although Dassen Island housed the nearest colony, most African penguins came from Namibia.

Penguins were forced to abandon their nests in droves in the 1980s in search of food and a new habitat. This led to young penguins settling down and starting new colonies along Stony Point and Boulders Beach.

Whales being processed in the area.

Before Stony Point was a feather-filled tourist attraction it was one of the areas associated with whaling between the 19th and 20th centuries. In 1912, 60 hectares of land including Stony Point was leased to Captain Cook who established The Southern Cross Whaling Company Ltd, profiting from the horrors of whaling.

A whaling station was established in the area and roughly 173 whales were killed in the seas off Cape Hangklip in 1913 and 84 in 1914.

Between 1916 and 1920, 300 whales were killed each year by steam ships that operated from the Stony Point whaling station and 144 people were employed in the grim business.

In 1976 whaling was outlawed and the dark years were left behind when Cape Nature upgraded the area due to its historical significance and welcomed the penguin colony we know today.

An old photo of Simon’s Town where Boulders Beach is located.

Unsurprisingly named after its giant granite boulders, this much-loved destination only welcomed penguins in 1983.

The colony has increased to over 3 000 strong but was started by just two breeding pairs spotted on Foxy Beach by locals roughly 37 years ago. The beach is enclosed, surrounded by boulders believed to be some 540-million years old.

Before, the beach was somewhat lonely without the little flightless birds to liven up the atmosphere, and now it is one of only two areas in Cape Town that the endangered African penguins call home.

Pictures: Cape Town Down Memory Lane/Michael Nicoll

Sources:

http://www.theheritageportal.co.za

https://www.simonstown.com/penguins

https://www.aquarium.co.za/blog/

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 76089

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: African Penguin

Very good, who knew?!

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67563

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: African Penguin

Never knew that it was so recent

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

-

Michele Nel

- Posts: 1912

- Joined: Mon Sep 10, 2012 10:19 am

- Country: South Africa

- Location: Cape Town

- Contact:

Re: Your Best Photo of Animal(s) in Water

So this is not the image I have been trying to upload ....but this one seems to be working. I will get to the bottom of my uploading problem eventually.

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5862

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

Re: African Penguin

Have moved Michele's photo to this topic.

And here un update on the populations in SA

http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/fa ... ersus/text

And here un update on the populations in SA

http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/fa ... ersus/text

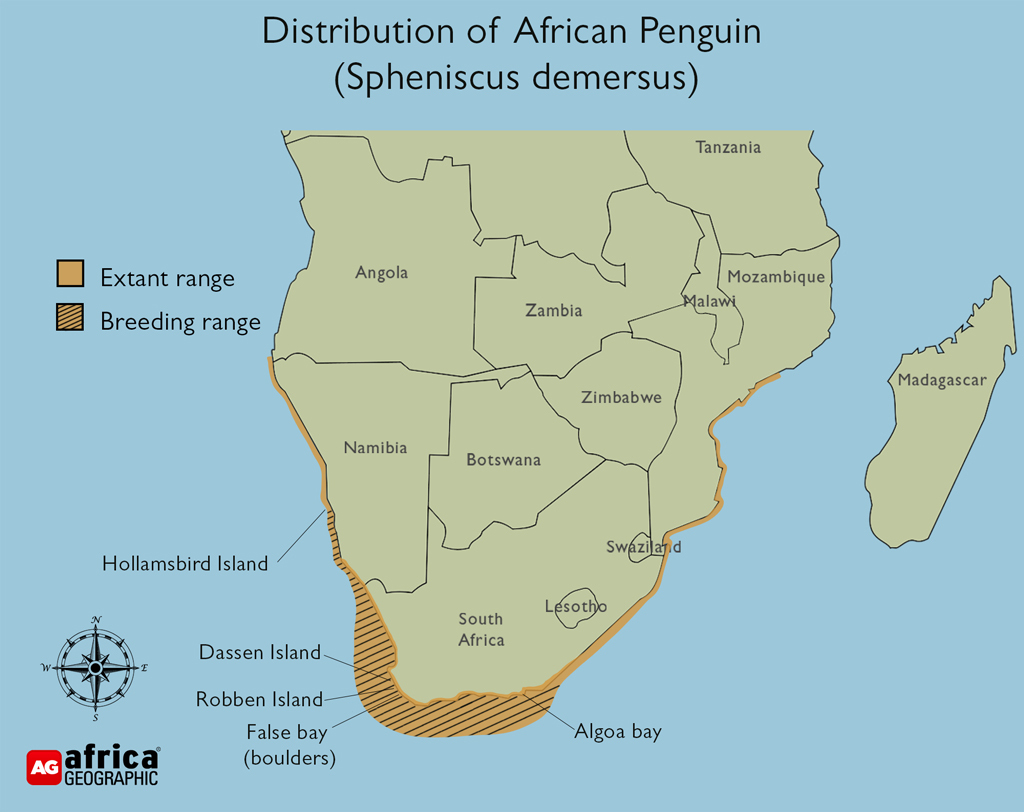

Distribution and population

Spheniscus demersus is endemic to southern Africa, where it breeds at 28 localities in Namibia and South Africa (Kemper et al. 2007b, Crawford et al. 2013, Kemper 2015). It has been recorded as far north as Gabon and Mozambique (Crawford et al. 2013).

In Namibia, Neglectus Islet and Penguin Island were recolonised in 2001 and 2006 respectively (Kemper et al. 2007a). In the 1980s, the species colonised Stony Point and Boulders Beach on the South African mainland and recolonised Robben Island, all in the southwest of the country (Underhill et al. 2006). A colony formed on the southern mainland at De Hoop in 2003, but disappeared after 2007. The northernmost colony at Lambert’s Bay became extinct in 2006 (Underhill et al. 2006, Crawford et al. 2011).

In 2015, the population for Namibia was estimated at 5,700 to 5,800 pairs (MFMR unpubl. data), the uncertainty in the estimate arising from a few islands that had not been counted for several years (J. Kemper pers. comm.). The most important colonies were Mercury Island: 2,646 pairs, Ichaboe Island: 488 pairs, Halifax Island: 1,092 pairs and Possession Island: 1,205 pairs (MFMR unpubl. data).

In 2019, c.13,300 pairs bred in South Africa: St Croix Island: 3,638 pairs, Bird Island (Algoa Bay): 2,378 pairs, Dassen Island: 1,912 pairs, Stony Point: 1,705 pairs , Robben Island: 1,190 pairs, Dyer Island: 1,071 pairs, Simonstown: 932 pairs (Department of Environmental Affairs, SANParks and CapeNature unpubl. data). Just seven colonies now support 97% of the South African population. Recent declines at South African colonies are coincident with changes in the abundance and availability of forage fish and an eastward movement of spawning forage fish (Crawford et al. 2011, Waller 2011, Sherley et al. 2014a).

Ecology

Behaviour Adults are largely resident, but some movements occur in response to prey movements (Hockey et al. 2005). Adults generally remain within 400 km of their breeding locality, although they have been recorded up to 900 km away (Hockey et al. 2005, Roberts 2015). They breed and moult on land before taking to the sea, where they can remain for up to four months (Crawford et al. 2013, Roberts 2015). On gaining independence, juveniles disperse up to 2,000 km from their natal colonies, with those from the east heading west, and those from the west and south moving north (Sherley et al. 2013a, Sherley et al. 2017). Most birds later return to their natal colony to moult and breed (Randall et al. 1987, Sherley et al. 2014a), although the growth of some colonies has been attributed to the immigration of first-time breeders tracking food availability (Crawford 1998, Crawford et al. 2013). Adults nest colonially, but may also nest in isolation. At sea they forage singly, in pairs or sometimes co-operatively in small groups of up to 150 individuals (Wilson et al. 1986, Kemper et al. 2007b, Ryan et al. 2012, McInnes et al. 2019). African Penguins forage more successfully in groups when feeding on schooling fish (McInnes et al. 2017). The species breeds year round with peak months varying locally (Crawford et al. 2013). In the north-western part of the range, peak laying occurs during the months of November to January; in the south-west it occurs between May and July, and in the east between April and June (Crawford et al. 2013). The average age at first breeding is thought to be 4-6 years (Whittington et al. 2005).

Habitat This species is marine and usually found within 40 km of the coast (Wilson et al. 1988, Petersen et al. 2006, Pichegru et al. 2009, 2012), coming ashore on islands or at non-contiguous areas of the mainland coast to breed, moult and rest (Hockey et al. 2005). Breeding: Breeding habitats range from flat, sandy islands with varying degrees of vegetation cover, to steep rocky islands with little vegetation (Hockey et al. 2005). African Penguins are sometimes found close to the summit of islands and may move over a kilometre inland in search of breeding sites (Hockey 2001). They usually feed within 20 km of the colony when breeding, although at some colonies the distance is greater (Pichegru et al. 2009, Waller 2011, Ludynia et al. 2012, Pichegru et al. 2012). Non-breeding: At sea, their distribution is mainly restricted to the greater Benguela Current region (Williams 1995). Juveniles have been observed to travel ~600 km from their natal colonies (Sherley et al. 2017), while immatures up to 700 km with an average of ~370 km from the colony (Grigg and Sherley 2019). Pre- and post moulting adults have been observed up to 550 km from their colonies (de Blocq et al. 2019).

Diet Adults feed predominantly on pelagic schooling fish of 50-120 mm length, with important prey including sardine Sardinops sagax, anchovy Engraulis capensis, bearded goby Sufflogobius bibarbatus and round herring Etrumeus whiteheadi (Crawford et al. 1985, Ludynia et al. 2010, Crawford et al. 2011). In some localities, cephalopods represent an important food source (Crawford et al. 1985, Connan et al. 2016). Juveniles are thought to prey on fish larvae (Wilson 1985).

Breeding site In the past, nests were usually built in burrows dug in guano or sand (Frost et al. 1976a, Shelton et al. 1984). Today, with the lack of guano at most colonies, nesting in open areas has become increasingly common (Kemper et al. 2007b, Sherley et al. 2012, Pichegru 2013). At some sites, artificial nest-burrows made from pipes and boxes sunken into the ground, and shelters shaped from dry vegetation have been regularly used by the species (Kemper et al. 2007a, Sherley et al. 2012, Pichegru 2013).

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 76089

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: African Penguin

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67563

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: African Penguin

SOUTHERN AFRICA'S ENDANGERED TUXEDOED TREASURE

Thursday, 5 January 2023

For most people, “penguin” immediately brings to mind an image of hunched figures huddled together, braced against the icy winds of the long Antarctic night – possibly accompanied by the soothing tones of David Attenborough. It is not a word that conjures the image of tuxedoed little birds sharing their space with bikini-clad summer holidaymakers on the sweltering beaches of South Africa. And yet, that is precisely what thousands of tourists flock to see: the endangered African penguins of the Cape.

THE AFRICAN PENGUIN

The African penguin (Spheniscus demersus) is found on the southwestern coast of Africa in established colonies on 24 different islands and rocks off the Namibian and South African shorelines. While they breed within this range, their presence has been recorded as far north as Gabon and Mozambique. Historically, penguins avoided mainland nesting sites due to the risk of large-animal predation, particularly by leopards, caracals and jackals. However, a burgeoning human population reduced potential threats and kept large predators at bay. As a result, the first trailblazing penguin pairs began to nest on the mainland around forty years ago. Today, the two best-known mainland colonies are in South Africa, one at Boulders Beach in Simon’s Town and the other at Stony Point in Betty’s Bay.

The penguins proved to be quite happy to adapt to life among people, and from one breeding pair in 1985, Simon’s Town now welcomes over 1,000 couples every year. The penguins merrily trundle over beach blankets, walk the town’s streets, nest in gardens and irritably snap sharp beaks at ankles that stray too close to their eggs. Presumably unconcerned by their own celebrity, these charming little characters all but take over the town, attracting droves of visitors eager to observe their Spheniscidae antics.

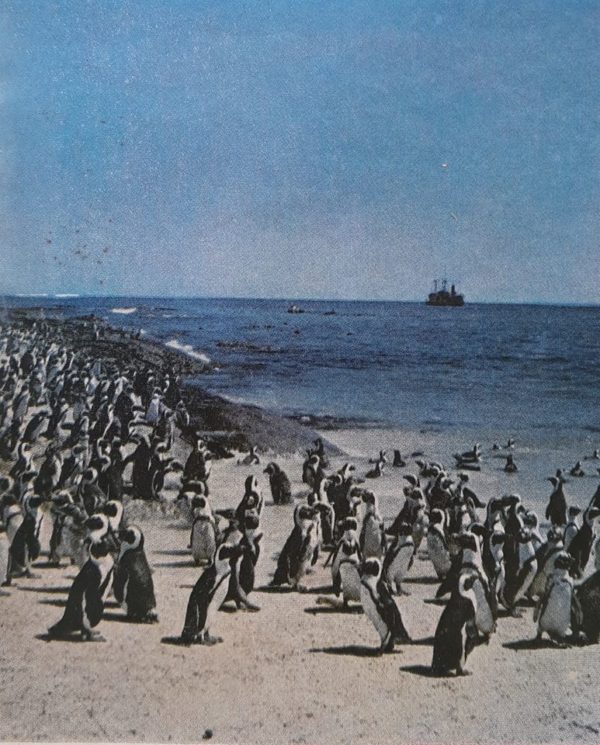

Members of the African Penguin colony at Boulders Beach in South Africa gather at the water’s edge

Observers are well-rewarded because the penguins are endlessly entertaining. Part of their appeal is that they are easy to anthropomorphise. Their black-and-white markings are positively debonair, and the bare pink patch of skin (which has a thermoregulatory function) gives the impression of cynically raised eyebrows. Touchingly, African penguins are monogamous, often returning year after year with the same partner to raise the next generation as a dedicated team. They are also innately comical. Though webbed feet and flipper wings are perfect for the open seas, they do not make for good land legs, and African penguins are endearingly clumsy when out of the water. Throw in the donkey-like bray of their call (hence the former name, the jackass penguin) and the scene is set for genuine amusement.

Yet as delightful as the tableau of beaches packed with penguins may be, the truth is that African penguins face a sobering future. Their populations are believed to be just 2% of what they were at the start of the 20th century, and a 2019 count yielded a historic low of less than 21,000 breeding pairs.

A pair of penguins groom one another – their black and white markings, and bare pink patch of skin creating a striking image

QUICK FACTS ABOUT THE AFRICAN PENGUIN

Height: 60-70cm

Mass: 2.2-3.5kg (males slightly larger)

Social structure: Monogamous pairs, breeding colonies

Incubation period: 40 days

Conservation status: Endangered

FISH, FEATHERS AND FUZZ

The penguins’ decline over the past century can be partly attributed to the horrendous exploitation of their eggs, which were enjoyed as a delicacy by their thousands until the 1970s. However, the population has declined by over 65% in the last twenty years. One of the primary reasons for this is the decrease in prey availability due to climate change and the commercial overfishing of the oceans. African penguins hunt oil-rich pelagic fish species such as sardines and anchovies but are increasingly reliant on squid, octopus, krill and shrimp to supplement their diets.

A food shortage can be particularly detrimental before and after their moulting period. Once every year, adult penguins undergo a so-called “catastrophic” moult. They return to land to replace old and damaged feathers with a new, healthy covering of insulating, waterproof plumage. This process takes two to five weeks, during which the penguin is totally land-bound, dishevelled and understandably cantankerous. Unable to hunt, they will lose 40-50% of their body mass before returning to the water. To survive this ordeal, they must bulk up ahead of time and work hard to recover condition afterwards. And they have to travel further and further to find the food they need.

Once every year, adult African penguins undergo a “catastrophic” moult. During this time, penguins are land-bound

ALL HANDS (AND FLIPPERS) ON DECK

Complete with a brand-new suit, the next arduous mission can begin. Finding a mate is the first order of business for newly fledged adults (aged four to six) ready to breed for the first time. A suitable partner is wooed by a complex dance of head twisting, bowing and beak tapping. If the seduction is successful, the honeymooners search for a suitable nest site. The pressure on this budding relationship is substantial: if breeding fails for any reason, the penguins waste little time laying blame and separate in search of a new partner.

Unlike their cousins in Antarctica, the African penguins are more concerned with keeping the eggs safe from scorching temperatures and blazing sunlight. The thick layers of guano on the islands provide the perfect nesting material, but sandy depressions, rock crevices, and manmade structures are utilised on the mainland. The best nesting sites (those with ample shade, or a cooling breeze, for example) are at a premium and aggressively defended by those couples fortunate enough to snag them. Penguin pairs that have established a successful nesting site in the past will opt to return to it year after year.

The female will lay one or two eggs, and the couple shares the 40-day incubation period, defending the eggs from seagulls, mongooses, and even other penguins (especially frustrated singles). The tiny chicks hatch as fluffy brown bundles with white bellies, ravenous appetites, and disproportionately prominent voices. Their parents will take turns heading out to hunt, braving tides, rocks and hungry Cape fur seals to return with a massive belly full of fish. It is a dangerous journey, and on occasion, one parent may not return, leaving their now solitary partner to raise the chicks as a single parent.

The first chick to hatch will always be the stronger of two siblings, but unlike birds of prey, penguins often successfully raise two chicks from one clutch. The younger sibling may have to wait for an older brother or sister to leave home before they can monopolise their parents’ attention. However, dwindling food supplies have placed increasing pressure on parental penguins, and under dire circumstances, the second chick may be left to starve.

A growing penguin chick fed on hearty meals of regurgitated fish porridge can fledge in as little as 60 days and join its peers on the beach in a crèche. Here they will gather their courage (and learn the tidal ropes) before setting out for a few years spent predominantly at sea. In the open waters, they will encounter fish for the first time and will have to learn the group hunting techniques practised by the adults. This oceanic initiation claims about 60% of all fledgling penguins. The survivors return to land to moult and grow their adult plumage, complete with a fingerprint pattern of black spots on their white undersides.

The grey plumage of sub-adult African penguins is distinctly different from that of their parents

BETWEEN THE DEVIL AND THE DEEP BLUE

Unsurprisingly, the beguiling African penguins have won over thousands of ardent fans since they first waddled onto the mainland. Several organisations are working hard to halt the population decline. This conservation work involves everything from monitoring and studying existing colonies to dealing with once-off disaster events like oil spills from tankers.

SANCCOB (the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds) takes in around 1,000 birds annually. Abandoned chicks are hand-reared, and sick or injured birds are treated and released back into the wild. In addition, BirdLife South Africa’s African Penguin Conservation project, in partnership with SANCCOB and CapeNature, is working to establish a breeding colony at De Hoop Nature Reserve, with successful breeding milestones already achieved in the project. (You can read more about their project and contribute to this work by logging into our app. If you do not yet have our app see the instructions below this story.)

Naturally, the African penguin’s most crucial conservation concern is competition with commercial fisheries and subsequent declining fish stocks. Fortunately, the industrial fishing ban around False Bay dating back to the 1980s has dramatically benefited the penguins of both Simon’s Town and Stony Point. A temporary restriction around Robben Island was also shown to improve breeding success rates.

African penguins are under threat due to declining fish stocks

WHERE AND WHEN?

Penguins are usually present and may be encountered year-round at Boulders and Foxy Beaches in Simon’s Town and Stony Point Nature Reserve in Betty’s Bay. However, many adult birds spend their time at sea outside the breeding season. The best penguin viewing starts during the summer (around December), and by April, the breeding season reaches its zenith, and the beaches and surrounds are packed with besuited penguins. In South Africa, most penguins moult between September and January, making this the best time of year to encounter them in various states of déshabillé.

It is important to remember that as comfortable as the penguins are waddling among people, they should be given the appropriate space and respect. African penguins may be cute, plucky, sassy or any other number of anthropomorphic adjectives we can think of, but they are still endangered wild animals. And they have razor-sharp beaks.

African penguins are monogamous, returning year after year with the same partner to raise the next generation as a dedicated team

- Attachments

-

- AG-STORIES.png (2.88 KiB) Viewed 564 times

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge