Fracking in SA could be a game-changer or a damp squib

Oct 09 2017 07:29 Professor Robert Scholes

South Africa's Karoo region potentially holds shale gas that could transform the energy economy of the country. But given the uncertainties around exploration what's the next logical step, asks Professor Robert Scholes.

Horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, otherwise known as fracking, has in the past few decades made available the gas in previously ‘tight’ shale geologies. This has shaken up the energy sector worldwide by contributing to relatively low oil prices. Almost all the shale gas development has taken place in the US where production has increased from about 1 to nearly 16 trillion cubic feet (tcf) over the past 25 years.

There are indications that shale gas may be present in a semi-desert region of South Africa known as the Karoo. The core region alone has an area of 400 000 km². If a viable gas resource were to be developed in the Karoo, what impact would it have on the global shale gas market? And how would it affect the energy economy of South Africa?

A few preliminary studies have been done on the potential for shale gas in the country. These include a report on the technical readiness for a shale gas industry in South Africa, a strategic environmental assessment on shale gas development commissioned by the Department of Environment which I co-led, and a multi-author academic book on hydraulic fracturing in the Karoo.

The research, presented at a recent conference, has led to a clearer picture of both the potential, and the challenges facing shale gas extraction in South Africa. The purpose of the conference, organised by the Academy of Science of South Africa, was to map out a multidisciplinary research plan to fill the critical knowledge gaps.

How much, how little?

The studies to date suggest that it’s increasingly unlikely that economically and technically viable gas will be found in the Karoo. First desktop estimates of gas-in-place at depth in the Karoo basin were hundreds of tcf.

More realistic guesses – which is what they remain, in the absence of new exploration and testing – put the upper limit for gas in the Central Karoo at about 20 tcf. This is a tiny resource by global standards. In terms of energy content, 20 tcf of gas is about forty times smaller than the known remaining coal reserves in South Africa. Conventional gas reserves offshore of Mozambique have been estimated at 75 tcf. On the other hand, the continental shelf gas field off Mossel Bay located on South Africa’s garden route, exploited and now nearly depleted, was 1 tcf.

A viable gas find in South Africa, even if quite small, would potentially transform the national energy economy. But making a large investment in infrastructure, regulatory tools, monitoring bodies, and wellfield development for a resource which may not exist is financially, politically and environmentally risky.

Any decisions about how the country should proceed must therefore be based on solid research which is why efforts are under way to adopt a multidisciplinary research programme to fill in the key knowledge gaps. On top of this, good governance is a prerequisite if South Africa is to proceed to shale gas development.

South Africa’s energy mix

South Africa’s formal energy economy is dominated by coal. But that cannot continue, as the country’s cheap, easily accessible coal reserves are nearing an end. Coal mining has also devastated important agricultural and water-yielding landscapes. Financial institutions are increasingly reluctant to fund new coal-burning power stations because of the impact carbon dioxide emissions are having on the global climate.

As a result, coal-burning power stations are likely, over time, to be replaced by wind and solar energy, or perhaps the more expensive nuclear option. But the degree to which the country’s energy supply can be based on intermittent sources like wind and sunshine depends on the availability of an energy source that can be easily switched on or off to fill the temporary shortfalls between supply and demand – like gas-fired turbines.

South Africa has already decided to increase the fraction of gas in its energy mix. The only question is where to source it from. Are international imports or domestic sources, like offshore conventional gas or onshore unconventional gas, including shale gas and coal-bed methane better?

Next steps

The optimal approach would be to take the first exploratory steps cooperatively, and in the public-domain, rather than in a competitive, secretive and proprietary way. This would allow South Africa to learn about the deep geology of the Karoo and the technologies and hazards of deep drilling, even if no viable gas was found.

A “virtual wellfield”, an imaginary but realistic computer simulation, could be developed on the basis of these findings. This would allow decision-makers and the public to better understand the economic spinoffs and environmental hazards of gas development before any significant actual development occurs.

The continuing low price of oil and the reduced demand for energy caused by the faltering South African economy buy the country time to do the necessary research and exploration. It can establish the appropriate regulatory environment and institutions before making rushed decisions with large potential consequences.

This is a cautious, evidence-guided agenda which should be acceptable to most people who care both about national development and the quality of the environment.

This article is the first in a series The Conversation Africa is running on shale gas in South Africa.

The ConversationThis article is the first in a series The Conversation Africa is running on shale gas in South Africa.

Professor Robert Scholes is a Systems Ecologist at the Global Change Institute (GCI) at the University of the Witwatersrand.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

http://www.fin24.com/Opinion/fracking-i ... b-20171009

Fracking in Southern Africa - General

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75552

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Fracking in Southern Africa - General

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75552

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Fracking in South Africa - General

Brilliant summation!

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 66701

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Fracking in South Africa - General

Fracking with CO2 instead of water could be more efficient - study

31.05.2019 | AFP

Carbon dioxide appears to be more efficient than water for hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, to extract oil and natural gas, according to a study led by scientists in China published on Thursday.

Fracking is a process by which high-pressure fluids are injected into underground rock to create cracks to release oil and gas.

In the United States, fracking has fueled an oil boom since the early 2000s.

Currently, the most widespread method involves using large quantities of water mixed with chemicals.

But the method is controversial because the fluids are suspected of contaminating the aquifer - the underground layer of permeable rock that bears water - and of triggering mini-earthquakes.

The use of carbon dioxide instead of water to reduce the environmental impact of fracking has been the subject of studies for years.

Scientists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and China University of Petroleum in Beijing tested the method in a lab and in five wells at the Jilin oil field in northeastern China.

"To our delight, oil production increased by (around) four- to 20-fold after the entire CO2 fracturing process" compared to the use of a water-chemical mix, wrote the authors of the study published in the American journal Joule.

The experts said carbon dioxide is better at breaking up the shale.

"These real-world results revealed that as compared to water fracturing, CO2 fracturing is an important and greener alternative, particularly for reservoirs with water-sensitive formations, located at arid areas, or other conditions that making water fracturing less applicable," the authors added.

This would hold especially true in arid regions, where water currently needs to be transported by tanker trucks.

The scientists argue that this technique would allow CO2 - the main greenhouse gas emitted by human activity blamed for global warming - to be trapped in the ground, thereby removing it from the atmosphere.

However, injecting CO2 to extract hydrocarbons whose combustion would lead to more carbon emissions can seem counter-productive.

"CO2 fracking might ultimately have environmental benefits compared to fracking with water, but this study does not include the analysis that is needed to establish whether CO2 fracking is likely to lead to an overall reduction in global greenhouse gas emissions," said Hannah Chalmers, a senior lecturer at the University of Edinburgh.

31.05.2019 | AFP

Carbon dioxide appears to be more efficient than water for hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, to extract oil and natural gas, according to a study led by scientists in China published on Thursday.

Fracking is a process by which high-pressure fluids are injected into underground rock to create cracks to release oil and gas.

In the United States, fracking has fueled an oil boom since the early 2000s.

Currently, the most widespread method involves using large quantities of water mixed with chemicals.

But the method is controversial because the fluids are suspected of contaminating the aquifer - the underground layer of permeable rock that bears water - and of triggering mini-earthquakes.

The use of carbon dioxide instead of water to reduce the environmental impact of fracking has been the subject of studies for years.

Scientists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and China University of Petroleum in Beijing tested the method in a lab and in five wells at the Jilin oil field in northeastern China.

"To our delight, oil production increased by (around) four- to 20-fold after the entire CO2 fracturing process" compared to the use of a water-chemical mix, wrote the authors of the study published in the American journal Joule.

The experts said carbon dioxide is better at breaking up the shale.

"These real-world results revealed that as compared to water fracturing, CO2 fracturing is an important and greener alternative, particularly for reservoirs with water-sensitive formations, located at arid areas, or other conditions that making water fracturing less applicable," the authors added.

This would hold especially true in arid regions, where water currently needs to be transported by tanker trucks.

The scientists argue that this technique would allow CO2 - the main greenhouse gas emitted by human activity blamed for global warming - to be trapped in the ground, thereby removing it from the atmosphere.

However, injecting CO2 to extract hydrocarbons whose combustion would lead to more carbon emissions can seem counter-productive.

"CO2 fracking might ultimately have environmental benefits compared to fracking with water, but this study does not include the analysis that is needed to establish whether CO2 fracking is likely to lead to an overall reduction in global greenhouse gas emissions," said Hannah Chalmers, a senior lecturer at the University of Edinburgh.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Peter Betts

- Posts: 3080

- Joined: Fri Jun 01, 2012 9:28 am

- Country: RSA

- Contact:

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 66701

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Fracking in Southern Africa - General

Mystery shrouds plans to start fracking near Namibia’s Kavango River and Botswana’s Tsodilo Hills

By Jeffrey Barbee with editing by Kerry Nash• 16 September 2020

Max Thokobotshabelo, right, works in the northern part of the Okavango Delta. The Okavango Jakotsha Community Trust, a community-based organisation, represents the interests of these communities and helps share out the wealth generated by tourism. Guiding tourists helps Max provide food and schooling for his extended family. The Delta brings in most of the $500m that Botswana makes in sustainable tourism every year. (Copyright: Jeffrey Barbee / alianceearth.org)

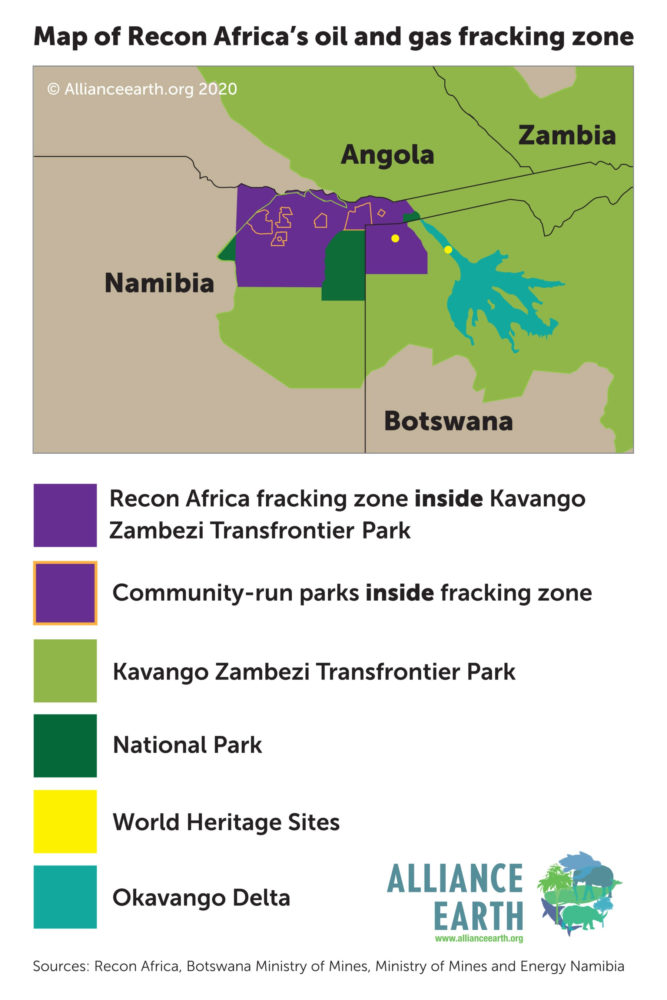

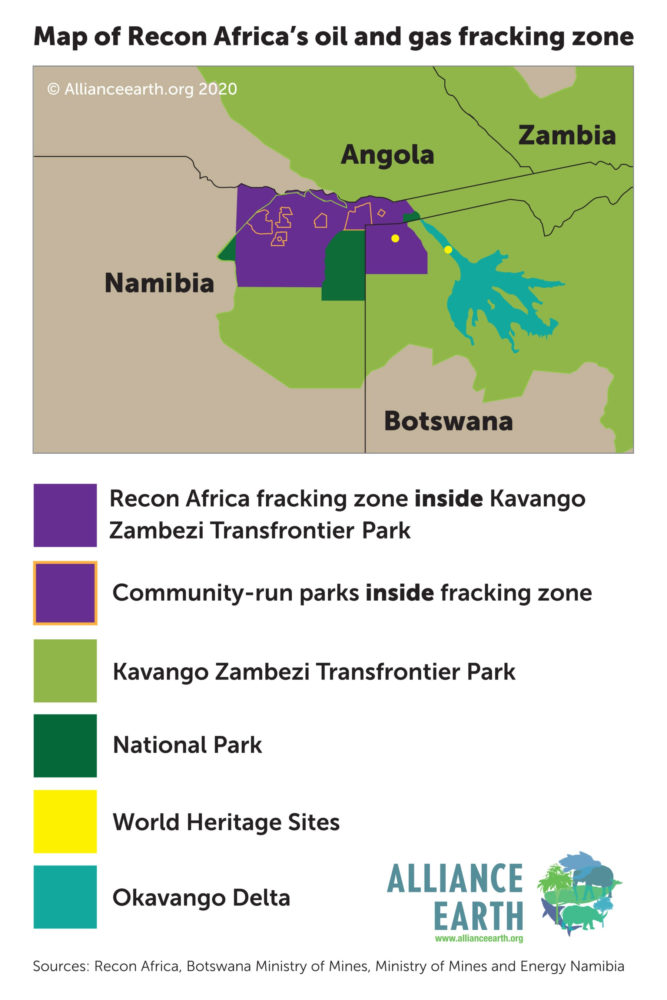

A Canadian oil and gas exploration company, ReconAfrica, says it has the go-ahead to frack in some of Africa’s most sensitive environmental areas, including the Namibian headwaters of the Okavango Delta and the Tsodilo Hills, a World Heritage Site in Botswana. But they may have jumped the EIA gun.

Canadian oil and gas company ReconAfrica said in a press release last month that it is planning to drill oil and gas wells into an environmentally sensitive, protected area in Africa that supplies the Okavango Delta with water.

The drilling location sits along the banks of the Kavango River, straddling the border between Namibia and Botswana, inside the newly proclaimed Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area, the KAZA TFCA.

Lake Nguma in the north part of the Okavango Delta. The delta will be one of the centrepieces of the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area. (Copyright: Jeffrey Barbee / alianceearth.org)

ReconAfrica, which is listed on the Canadian TSX Venture Exchange, explains on its website that it has acquired the rights to drill in more than 35,000km2 of north-east Namibia and north-west Botswana. Maps from both the Namibian and Botswanan ministries of mines confirm that they have been granted petroleum prospecting licences in the area.

ReconAfrica claims that this new discovery could be bigger than the Eagle Ford shale basin in Texas, which the United States Energy Information Agency says is one of the largest terrestrial oil and gas finds in the world.

Halliburton sets up a large slick-water hydraulic frac, or fracture on a gas pad in Colorado on County Road 309 on Battlement Mesa. (Copyright: Jeffrey Barbee / alianceearth.org)

Oil and gas discoveries like the Eagle Ford Basin helped make the United States the largest oil and gas producer in the world, but have also created massive problems, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists. They explain in their Guide for Residents and Policy Makers Facing Decisions Over Hydraulic Fracturing that the negative impacts of hydraulic fracturing often include poor air and water quality, community health problems, safety concerns, long-term economic issues and environmental crises like habitat loss.

ReconAfrica’s exploration licenses border three national parks upstream of the Okavango Delta. They also cover 11 separate community conservancy concession areas, one World Heritage Site and part of the five-country KAZA TFCA, the largest protected area in southern Africa.

!Tsai, a San shaman, performs the healing dance in Botswana’s remote north-west. He and his people were moved out of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve and have struggled to keep their traditional ways of life as the climate changes. This part of the healing ritual is called the Dove Dance and is directed at the creator to help heal the land and the people. (Copyright: Jeffrey Barbee / alianceearth.org)

The drilling area also includes one of the last refuges of the Kalahari San with a future drill site near the World Heritage Site of Tsodilo Hills in Botswana. Unesco says the site holds 4,500 rock paintings “preserved in an area of only 10km2 of the Kalahari Desert. The archaeological record of the area gives a chronological account of human activities and environmental changes over at least 100,000 years”.

Namibian-born University of Cape Town social scientist Dr Annette Hübschle is very concerned about the impact of this fracking project on San communities in the area.

“Particularly worrisome is that First Nations people, the San peoples, are living in the region. They are already living on the margins of society – this is going to negatively impact their way of life, their livelihood strategies and the place they call home.”

Chris Brown is the CEO of the Namibian Chamber of Environment, an industry-funded environmental organisation that helps liaise between mining companies and affected communities in this country of 2.5 million people. He says that he has never heard anything about this potential shale oil find.

“I have spoken to a number of people to ask if anyone in the mining sector here had heard of this development and if anyone in the NGO sector had heard of it, and it seems to be totally under the radar here in Namibia.”

He says any kind of project like this should have gone through environmental review and permitting processes.

Fracking plots in the United States. (Copyright: Bruce Gordon / Ecoflight)

“There needs to be public consultation and we monitor all the adverts that come out in the newspapers and we monitor all the adverts that come out around EIAs and we haven’t picked this up at all.”

Brown says that an environmental impact assessment (EIA) is required by law in Namibia before any invasive activities like oil and gas drilling can be conducted.

Maxi Pia Louis is the director of the Namibian Association of Community Based Natural Resource Management Support Organisations. She is also concerned about the lack of consultation by ReconAfrica in the 11 community conservancy concessions included in the alleged prospecting licence area. “I have no idea about this. It is huge: if there was an EIA, I would have known because this is where a lot of our conservation projects are.”

Max Muyemburuko is the chairperson of the 615km² Muduva Nyangana Conservancy, which is covered by the prospecting licence in Namibia. He says that two years ago people came to their community saying they were “looking for energy”.

“We tried to get hold of their team leader to hear more about their mission, but they said no, we will come back to you after completing this research, but since then they never come back.” He says he is concerned that the company may have “made deals behind our backs, and we have no idea what kind of environmental impact they will have”.

Hübschle says this lack of communication is troubling given fracking’s social and environmental record in the US.

“We should be very concerned about the long-term impacts of fracking on livelihoods, health, ecosystems, biodiversity conservation and especially climate change.”

Fracking seems to be part of ReconAfrica’s plan. ReconAfrica’s CEO Scot Evans is the former vice-president of US industry giant Halliburton. He told industry journal Market Screener in June 2020 that ReconAfrica hired fracking pioneer Nick Steinsberger in June to run the Namibian drilling project, saying, “Nick is the pioneer of ‘slickwater fracs’.” He goes on to say that hydraulic fracturing is “a technique now utilised in all commercial shale plays worldwide”.

The area is home to Africa’s largest migrating elephant population as well as endangered African wild dogs and sable antelope. It is also a cornerstone of Namibia and Botswana’s tourism economy, which brings in about $500-million a year in sustainable tourism revenue.

The Kavango River, in the north of the potential fracking zone, is the sole provider of water to the Okavango Delta, Botswana’s most visited tourist attraction. This lifeline in the desert supports more than a million people in the region with food, employment and fresh water, according to scientist Dr Anthony Turton.

ReconAfrica says it is refurbishing a big drilling rig in Houston and will ship it to Namibia in October to begin drilling as soon as November or December 2020. On its website, ReconAfrica says it owns 90% of the Namibian side of the shale deposit, with the government-run Petroleum Company of Namibia owning the rest. This is “neo-colonial extraction of the worst sort”, says Hübschle, “where Namibians draw the shorter straw and foreign companies walk away with our mineral wealth”.

Namibian Chamber of Environment CEO Chris Brown is not sure if ReconAfrica has been granted the right to drill yet because it does not seem to have followed the letter of the law, including the public participation and environmental review processes necessary in Namibia. He says that “during Covid there might be ways around this process, like doing it remotely or through something like Zoom, but doing away with it completely would be illegal”.

The Covid-19 crisis has reduced global energy prices so much that many marginal fracking companies are going out of business across the United States. Bloomberg News reports that investors are running for the hills, bankrupting shale companies that often didn’t make a lot of money for investors anyway.

Namibia’s Ministry of Environment and Tourism has shared an EIA that was done to cover the drilling of three wells by ReconAfrica, yet many members of the government, affected communities and civil society are still in the dark about this development.

In nearby South Africa, Shell has been trying to frack a large area in the Karoo for more than 11 years, but has been delayed in part by strong environmental groups like Frack Free South Africa.

Frack Free South Africa director Judy Bell is concerned about the fracking plan for the KAZA TFCA, saying that “the world is hurtling toward a point of no return due to climate heating, caused by the extraction, storage and use of fossil fuels. We have no time left, so let’s leave the oil in the ground and use the naturally abundant sources of energy from the wind and the sun”. DM

For more information visit https://allianceearth.org/fracking-the-okavango

Jeffrey Barbee is an award-winning writer and filmmaker whose 2015 film The High Cost Of Cheap Gas helped expose an illegal attempt to run fracking operations on gas discoveries in Botswana. His reporting appears in Daily Maverick, The Guardian, Thomson Reuters Foundation, PBS, National Public Radio, LinkTV and many other publications.

By Jeffrey Barbee with editing by Kerry Nash• 16 September 2020

Max Thokobotshabelo, right, works in the northern part of the Okavango Delta. The Okavango Jakotsha Community Trust, a community-based organisation, represents the interests of these communities and helps share out the wealth generated by tourism. Guiding tourists helps Max provide food and schooling for his extended family. The Delta brings in most of the $500m that Botswana makes in sustainable tourism every year. (Copyright: Jeffrey Barbee / alianceearth.org)

A Canadian oil and gas exploration company, ReconAfrica, says it has the go-ahead to frack in some of Africa’s most sensitive environmental areas, including the Namibian headwaters of the Okavango Delta and the Tsodilo Hills, a World Heritage Site in Botswana. But they may have jumped the EIA gun.

Canadian oil and gas company ReconAfrica said in a press release last month that it is planning to drill oil and gas wells into an environmentally sensitive, protected area in Africa that supplies the Okavango Delta with water.

The drilling location sits along the banks of the Kavango River, straddling the border between Namibia and Botswana, inside the newly proclaimed Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area, the KAZA TFCA.

Lake Nguma in the north part of the Okavango Delta. The delta will be one of the centrepieces of the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area. (Copyright: Jeffrey Barbee / alianceearth.org)

ReconAfrica, which is listed on the Canadian TSX Venture Exchange, explains on its website that it has acquired the rights to drill in more than 35,000km2 of north-east Namibia and north-west Botswana. Maps from both the Namibian and Botswanan ministries of mines confirm that they have been granted petroleum prospecting licences in the area.

ReconAfrica claims that this new discovery could be bigger than the Eagle Ford shale basin in Texas, which the United States Energy Information Agency says is one of the largest terrestrial oil and gas finds in the world.

Halliburton sets up a large slick-water hydraulic frac, or fracture on a gas pad in Colorado on County Road 309 on Battlement Mesa. (Copyright: Jeffrey Barbee / alianceearth.org)

Oil and gas discoveries like the Eagle Ford Basin helped make the United States the largest oil and gas producer in the world, but have also created massive problems, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists. They explain in their Guide for Residents and Policy Makers Facing Decisions Over Hydraulic Fracturing that the negative impacts of hydraulic fracturing often include poor air and water quality, community health problems, safety concerns, long-term economic issues and environmental crises like habitat loss.

ReconAfrica’s exploration licenses border three national parks upstream of the Okavango Delta. They also cover 11 separate community conservancy concession areas, one World Heritage Site and part of the five-country KAZA TFCA, the largest protected area in southern Africa.

!Tsai, a San shaman, performs the healing dance in Botswana’s remote north-west. He and his people were moved out of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve and have struggled to keep their traditional ways of life as the climate changes. This part of the healing ritual is called the Dove Dance and is directed at the creator to help heal the land and the people. (Copyright: Jeffrey Barbee / alianceearth.org)

The drilling area also includes one of the last refuges of the Kalahari San with a future drill site near the World Heritage Site of Tsodilo Hills in Botswana. Unesco says the site holds 4,500 rock paintings “preserved in an area of only 10km2 of the Kalahari Desert. The archaeological record of the area gives a chronological account of human activities and environmental changes over at least 100,000 years”.

Namibian-born University of Cape Town social scientist Dr Annette Hübschle is very concerned about the impact of this fracking project on San communities in the area.

“Particularly worrisome is that First Nations people, the San peoples, are living in the region. They are already living on the margins of society – this is going to negatively impact their way of life, their livelihood strategies and the place they call home.”

Chris Brown is the CEO of the Namibian Chamber of Environment, an industry-funded environmental organisation that helps liaise between mining companies and affected communities in this country of 2.5 million people. He says that he has never heard anything about this potential shale oil find.

“I have spoken to a number of people to ask if anyone in the mining sector here had heard of this development and if anyone in the NGO sector had heard of it, and it seems to be totally under the radar here in Namibia.”

He says any kind of project like this should have gone through environmental review and permitting processes.

Fracking plots in the United States. (Copyright: Bruce Gordon / Ecoflight)

“There needs to be public consultation and we monitor all the adverts that come out in the newspapers and we monitor all the adverts that come out around EIAs and we haven’t picked this up at all.”

Brown says that an environmental impact assessment (EIA) is required by law in Namibia before any invasive activities like oil and gas drilling can be conducted.

Maxi Pia Louis is the director of the Namibian Association of Community Based Natural Resource Management Support Organisations. She is also concerned about the lack of consultation by ReconAfrica in the 11 community conservancy concessions included in the alleged prospecting licence area. “I have no idea about this. It is huge: if there was an EIA, I would have known because this is where a lot of our conservation projects are.”

Max Muyemburuko is the chairperson of the 615km² Muduva Nyangana Conservancy, which is covered by the prospecting licence in Namibia. He says that two years ago people came to their community saying they were “looking for energy”.

“We tried to get hold of their team leader to hear more about their mission, but they said no, we will come back to you after completing this research, but since then they never come back.” He says he is concerned that the company may have “made deals behind our backs, and we have no idea what kind of environmental impact they will have”.

Hübschle says this lack of communication is troubling given fracking’s social and environmental record in the US.

“We should be very concerned about the long-term impacts of fracking on livelihoods, health, ecosystems, biodiversity conservation and especially climate change.”

Fracking seems to be part of ReconAfrica’s plan. ReconAfrica’s CEO Scot Evans is the former vice-president of US industry giant Halliburton. He told industry journal Market Screener in June 2020 that ReconAfrica hired fracking pioneer Nick Steinsberger in June to run the Namibian drilling project, saying, “Nick is the pioneer of ‘slickwater fracs’.” He goes on to say that hydraulic fracturing is “a technique now utilised in all commercial shale plays worldwide”.

The area is home to Africa’s largest migrating elephant population as well as endangered African wild dogs and sable antelope. It is also a cornerstone of Namibia and Botswana’s tourism economy, which brings in about $500-million a year in sustainable tourism revenue.

The Kavango River, in the north of the potential fracking zone, is the sole provider of water to the Okavango Delta, Botswana’s most visited tourist attraction. This lifeline in the desert supports more than a million people in the region with food, employment and fresh water, according to scientist Dr Anthony Turton.

ReconAfrica says it is refurbishing a big drilling rig in Houston and will ship it to Namibia in October to begin drilling as soon as November or December 2020. On its website, ReconAfrica says it owns 90% of the Namibian side of the shale deposit, with the government-run Petroleum Company of Namibia owning the rest. This is “neo-colonial extraction of the worst sort”, says Hübschle, “where Namibians draw the shorter straw and foreign companies walk away with our mineral wealth”.

Namibian Chamber of Environment CEO Chris Brown is not sure if ReconAfrica has been granted the right to drill yet because it does not seem to have followed the letter of the law, including the public participation and environmental review processes necessary in Namibia. He says that “during Covid there might be ways around this process, like doing it remotely or through something like Zoom, but doing away with it completely would be illegal”.

The Covid-19 crisis has reduced global energy prices so much that many marginal fracking companies are going out of business across the United States. Bloomberg News reports that investors are running for the hills, bankrupting shale companies that often didn’t make a lot of money for investors anyway.

Namibia’s Ministry of Environment and Tourism has shared an EIA that was done to cover the drilling of three wells by ReconAfrica, yet many members of the government, affected communities and civil society are still in the dark about this development.

In nearby South Africa, Shell has been trying to frack a large area in the Karoo for more than 11 years, but has been delayed in part by strong environmental groups like Frack Free South Africa.

Frack Free South Africa director Judy Bell is concerned about the fracking plan for the KAZA TFCA, saying that “the world is hurtling toward a point of no return due to climate heating, caused by the extraction, storage and use of fossil fuels. We have no time left, so let’s leave the oil in the ground and use the naturally abundant sources of energy from the wind and the sun”. DM

For more information visit https://allianceearth.org/fracking-the-okavango

Jeffrey Barbee is an award-winning writer and filmmaker whose 2015 film The High Cost Of Cheap Gas helped expose an illegal attempt to run fracking operations on gas discoveries in Botswana. His reporting appears in Daily Maverick, The Guardian, Thomson Reuters Foundation, PBS, National Public Radio, LinkTV and many other publications.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75552

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Fracking in Southern Africa - General

An incredibly sensitive area!

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 66701

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Fracking in Southern Africa - General

It would influence a much bigger area than the one where the actual fracking would be concentrated

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 66701

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Fracking in Southern Africa - General

How fracking plans could affect shared water resources in southern Africa

October 18, 2020 | Surina Esterhuyse, Lecturer Centre for Environmental Management, University of the Free State

Fracking in the headwaters of the Okavango delta may negatively affect the water quality in this water source area. GettyImages

Recently, news reports revealed plans by a Canadian oil and gas company, ReconAfrica, to explore for oil and gas in some of Africa’s most sensitive protected areas. These areas include the Namibian headwaters of the Okavango delta and a world heritage site, Tsodilo Hills, in Botswana. Plans are afoot to explore inside the Kavango-Zambezi transfrontier conservation area.

Both conventional and unconventional oil and gas are the targets. Conventional oil and gas occur in porous geological formations. Unconventional oil and gas occur in impermeable geological formations and need specialised methods, such as fracking, to extract them.

Fracking is performed via deep wells drilled into the earth. A mixture of sand, water and chemicals is pumped in under high pressure to crack open the formation’s micro-fractures and release the trapped oil and gas.

The released gas returns to the surface together with wastewater. The wastewater may be radioactive and highly saline and some of the fracking chemicals may be toxic.

If these fluids migrate to freshwater aquifers through poorly sealed wells or aren’t correctly treated and disposed of, they could contaminate groundwater and surface water. Conventional gas extraction is less risky, but it too can threaten water resources if not properly managed.

As reported, ReconAfrica has acquired the rights to explore for oil and gas over an area of more than 35,000km². The Namibian Ministry of the Environment and Tourism stated that an environmental impact assessment was done before the exploration licence was awarded. But some environmental companies and members of government in Namibia remain in the dark about this development.

Public participation is required according to both Namibian and Botswana environmental impact assessment regulations.

Fracking impacts on shared water resources

Our review of the environmental impacts of unconventional oil and gas exploration has highlighted a number of concerns. They could be relevant in this case.

Seismic surveys might disturb vegetation or damage archaeological sites such as Tsodilo Hills. Fracking wells must also be drilled and fracked during the exploration phase, to assess the economic feasibility of extraction before proceeding to full scale production.

Of all the environmental impacts, the negative impact of fracking on water resources is the most serious concern. This is especially so in water-scarce countries such as Botswana, South Africa and Namibia.

What’s more, fracking in transfrontier parks may have transboundary impacts. Fracking in the headwaters of the Okavango delta within the Kavango-Zambezi transfrontier conservation area may negatively affect the water quality in this area and also the Okavango river water in Botswana and Namibia.

At least 70% of the 250 million people living in southern African countries rely on groundwater as their primary source of water. Shutterstock

Fracking in the Stampriet Transboundary Aquifer System that covers Botswana, Namibia and South Africa and where there are no permanent rivers, could have an impact on the groundwater of all three countries. Groundwater is extremely important to this region. The Stampriet Transboundary Aquifer System is the only permanent and dependable water resource for communities from central Namibia to western Botswana and South Africa’s Northern Cape province – an area that covers 87,000km².

Transboundary water resources cooperation

The impacts in these cases could cross national boundaries. So it’s essential to have transparency and cooperation between the governments that award oil and gas licences and the governments that may be affected. The Orange-Senqu River Commission promotes data sharing in the Southern African Development Community through the SADC Revised Protocol on Shared Watercourses.

International water law norms and treaties also require transboundary management to protect shared water resources. An important draft resolution that can help countries draw up agreements is the United Nations law of transboundary aquifers. Other relevant treaties are the Helsinki Convention and the Kiev Protocol on Strategic Environmental Assessment.

South Africa, Namibia and Botswana aren’t party to these treaties and are therefore not bound by them. The compliance of states with international norms cannot be enforced.

So the question is whether the benefits of joint water resources management will be clear enough to all states within the basin to foster cooperation.

Stakeholder governments must agree on how to regulate oil and gas exploration and production and on what data to share, without intruding upon any state’s sovereign authority. Where such cooperation doesn’t exist, it can lead to water disputes.

Fracking transparency

The apparent lack of transparency in sharing information about the licences is a worry. Without transparency, governments cannot properly manage or monitor the transboundary effects of exploration and fracking activities on the shared water resources.

A baseline of the water resources in the area before extraction is required. Monitoring of water resources during and after extraction is also needed. This will allow impacts on water quantity and quality to be measured.

Worldwide, transparency regarding unconventional oil and gas extraction activities is becoming increasingly important. The country that grants the licence should use regulations to obtain the necessary disclosures.

Information that isn’t protected by trade secrets should also be shared on a publicly accessible website such as Fracfocus. This would make it easier for fracking companies to obtain a social licence to operate. It would ultimately ensure that shared water resources are better managed and protected.

October 18, 2020 | Surina Esterhuyse, Lecturer Centre for Environmental Management, University of the Free State

Fracking in the headwaters of the Okavango delta may negatively affect the water quality in this water source area. GettyImages

Recently, news reports revealed plans by a Canadian oil and gas company, ReconAfrica, to explore for oil and gas in some of Africa’s most sensitive protected areas. These areas include the Namibian headwaters of the Okavango delta and a world heritage site, Tsodilo Hills, in Botswana. Plans are afoot to explore inside the Kavango-Zambezi transfrontier conservation area.

Both conventional and unconventional oil and gas are the targets. Conventional oil and gas occur in porous geological formations. Unconventional oil and gas occur in impermeable geological formations and need specialised methods, such as fracking, to extract them.

Fracking is performed via deep wells drilled into the earth. A mixture of sand, water and chemicals is pumped in under high pressure to crack open the formation’s micro-fractures and release the trapped oil and gas.

The released gas returns to the surface together with wastewater. The wastewater may be radioactive and highly saline and some of the fracking chemicals may be toxic.

If these fluids migrate to freshwater aquifers through poorly sealed wells or aren’t correctly treated and disposed of, they could contaminate groundwater and surface water. Conventional gas extraction is less risky, but it too can threaten water resources if not properly managed.

As reported, ReconAfrica has acquired the rights to explore for oil and gas over an area of more than 35,000km². The Namibian Ministry of the Environment and Tourism stated that an environmental impact assessment was done before the exploration licence was awarded. But some environmental companies and members of government in Namibia remain in the dark about this development.

Public participation is required according to both Namibian and Botswana environmental impact assessment regulations.

Fracking impacts on shared water resources

Our review of the environmental impacts of unconventional oil and gas exploration has highlighted a number of concerns. They could be relevant in this case.

Seismic surveys might disturb vegetation or damage archaeological sites such as Tsodilo Hills. Fracking wells must also be drilled and fracked during the exploration phase, to assess the economic feasibility of extraction before proceeding to full scale production.

Of all the environmental impacts, the negative impact of fracking on water resources is the most serious concern. This is especially so in water-scarce countries such as Botswana, South Africa and Namibia.

What’s more, fracking in transfrontier parks may have transboundary impacts. Fracking in the headwaters of the Okavango delta within the Kavango-Zambezi transfrontier conservation area may negatively affect the water quality in this area and also the Okavango river water in Botswana and Namibia.

At least 70% of the 250 million people living in southern African countries rely on groundwater as their primary source of water. Shutterstock

Fracking in the Stampriet Transboundary Aquifer System that covers Botswana, Namibia and South Africa and where there are no permanent rivers, could have an impact on the groundwater of all three countries. Groundwater is extremely important to this region. The Stampriet Transboundary Aquifer System is the only permanent and dependable water resource for communities from central Namibia to western Botswana and South Africa’s Northern Cape province – an area that covers 87,000km².

Transboundary water resources cooperation

The impacts in these cases could cross national boundaries. So it’s essential to have transparency and cooperation between the governments that award oil and gas licences and the governments that may be affected. The Orange-Senqu River Commission promotes data sharing in the Southern African Development Community through the SADC Revised Protocol on Shared Watercourses.

International water law norms and treaties also require transboundary management to protect shared water resources. An important draft resolution that can help countries draw up agreements is the United Nations law of transboundary aquifers. Other relevant treaties are the Helsinki Convention and the Kiev Protocol on Strategic Environmental Assessment.

South Africa, Namibia and Botswana aren’t party to these treaties and are therefore not bound by them. The compliance of states with international norms cannot be enforced.

So the question is whether the benefits of joint water resources management will be clear enough to all states within the basin to foster cooperation.

Stakeholder governments must agree on how to regulate oil and gas exploration and production and on what data to share, without intruding upon any state’s sovereign authority. Where such cooperation doesn’t exist, it can lead to water disputes.

Fracking transparency

The apparent lack of transparency in sharing information about the licences is a worry. Without transparency, governments cannot properly manage or monitor the transboundary effects of exploration and fracking activities on the shared water resources.

A baseline of the water resources in the area before extraction is required. Monitoring of water resources during and after extraction is also needed. This will allow impacts on water quantity and quality to be measured.

Worldwide, transparency regarding unconventional oil and gas extraction activities is becoming increasingly important. The country that grants the licence should use regulations to obtain the necessary disclosures.

Information that isn’t protected by trade secrets should also be shared on a publicly accessible website such as Fracfocus. This would make it easier for fracking companies to obtain a social licence to operate. It would ultimately ensure that shared water resources are better managed and protected.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 66701

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Fracking in Southern Africa - General

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

Threat of fracking looms large over Okavango Delta and other conservation areas

By Geoff Davies• 6 December 2020

If anyone argues that jobs and money will be made, know that the Okavango and its wildlife are of infinitely greater value.

You won’t believe it: A Canadian company is bringing a rig to Namibia and then to Botswana to ascertain the potential for fracking in – wait for it – the Okavango Delta and Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area in Botswana and northern Namibia.

Daily Maverick has already published an article on this (16 September 2020). Now the deadly rig is due in Walvis Bay on 9 December. Deadly, because you can only ascertain the potential for gas and oil by drilling, and thereby threatening the unique geological structure of the Okavango Delta.

ReconAfrica’s permit area in north eastern Namibia and northwestern Botswana fall wholly within the boundaries of the Kavango-Zambezi (KAZA) Transfrontier Conservation Area (TFCA) in which the international border of five nations converge.

Horrendous. Unbelievable that such a scheme could be proposed and planned, and even approved by the governments involved. A scheme that will destroy some of the most sacred and spectacular places, not only in Africa but the world.

This drilling will bring death to the Okavango Delta and its unique and teeming wildlife. It will bring death to the indigenous San people and their way of life. This is not only a matter of genocide but also ecocide. It is deeply sinful to destroy God’s creation.

How can anyone do it, you may ask, and how can anyone support it with finance? The answer is easy – for the money. Money in our contemporary world has become more important than life.

We call on all investment companies and all private financiers to refrain from investing in this nefarious venture. If anyone argues that jobs and money will be made, know that the Okavango and its wildlife are of infinitely greater value. If this area is fracked, it will be destroyed forever.

It is but one instance of our ongoing dash to death madness. No one, no company, no government should be putting money into exploration for and extraction of fossil fuels. We know we have to stop burning fossil fuels as a matter of urgency. We don’t have 10 years. We have to start turning the tide within the next two to three years. The glaciers, the ice caps, the Greenland ice are all melting — now! The tundra is thawing now, releasing methane. The forests are burning. The oceans are warming. The land temperatures are increasing. We must turn this tide now.

All the money that continues to go towards exploration for and subsidy of fossil fuels, can and must be invested now in renewable energy, into life for the future. DM

Bishop Geoff Davies, ‘The Green Bishop’, is the founder and honorary patron of the Southern African Faith Communities Environmental Institute, and retired Bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Umzumvubu.

Threat of fracking looms large over Okavango Delta and other conservation areas

By Geoff Davies• 6 December 2020

If anyone argues that jobs and money will be made, know that the Okavango and its wildlife are of infinitely greater value.

You won’t believe it: A Canadian company is bringing a rig to Namibia and then to Botswana to ascertain the potential for fracking in – wait for it – the Okavango Delta and Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area in Botswana and northern Namibia.

Daily Maverick has already published an article on this (16 September 2020). Now the deadly rig is due in Walvis Bay on 9 December. Deadly, because you can only ascertain the potential for gas and oil by drilling, and thereby threatening the unique geological structure of the Okavango Delta.

ReconAfrica’s permit area in north eastern Namibia and northwestern Botswana fall wholly within the boundaries of the Kavango-Zambezi (KAZA) Transfrontier Conservation Area (TFCA) in which the international border of five nations converge.

Horrendous. Unbelievable that such a scheme could be proposed and planned, and even approved by the governments involved. A scheme that will destroy some of the most sacred and spectacular places, not only in Africa but the world.

This drilling will bring death to the Okavango Delta and its unique and teeming wildlife. It will bring death to the indigenous San people and their way of life. This is not only a matter of genocide but also ecocide. It is deeply sinful to destroy God’s creation.

How can anyone do it, you may ask, and how can anyone support it with finance? The answer is easy – for the money. Money in our contemporary world has become more important than life.

We call on all investment companies and all private financiers to refrain from investing in this nefarious venture. If anyone argues that jobs and money will be made, know that the Okavango and its wildlife are of infinitely greater value. If this area is fracked, it will be destroyed forever.

It is but one instance of our ongoing dash to death madness. No one, no company, no government should be putting money into exploration for and extraction of fossil fuels. We know we have to stop burning fossil fuels as a matter of urgency. We don’t have 10 years. We have to start turning the tide within the next two to three years. The glaciers, the ice caps, the Greenland ice are all melting — now! The tundra is thawing now, releasing methane. The forests are burning. The oceans are warming. The land temperatures are increasing. We must turn this tide now.

All the money that continues to go towards exploration for and subsidy of fossil fuels, can and must be invested now in renewable energy, into life for the future. DM

Bishop Geoff Davies, ‘The Green Bishop’, is the founder and honorary patron of the Southern African Faith Communities Environmental Institute, and retired Bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Umzumvubu.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge