Big game parks vs big farming: A battle for the ages on the Klaserie River

By Kevin Bloom• 14 June 2021

View from a cliff above the southern shore of the Olifants River in the Kruger National Park. (Photo: Flickr / Ikka)

On a small plot of land outside Hoedspruit, a fight has been brewing that goes to the very heart of South Africa’s environmental legislation. One of the country’s largest citrus exporters is taking on 15 of the biggest brands in nature conservation, with the provincial authorities so far favouring the former. If the final battle is lost, say the conservationists, it will be open season on the region’s ecological treasures.

View from a cliff above the southern shore of the Olifants River in the Kruger National Park. (Photo: Flickr / Ikka)

On a small plot of land outside Hoedspruit, a fight has been brewing that goes to the very heart of South Africa’s environmental legislation. One of the country’s largest citrus exporters is taking on 15 of the biggest brands in nature conservation, with the provincial authorities so far favouring the former. If the final battle is lost, say the conservationists, it will be open season on the region’s ecological treasures.

“Insects form the base that supports intricate food webs.”

With this statement of fact, included in a report that detailed the likely impact of a proposed citrus farm on the Klaserie River basin, the ecologist Jessica Wilmot was echoing the work of Rachel Carson.

Published in 1962, Carson’s Silent Spring was an investigative masterpiece; an exposé of the catastrophe in the world of beetles and bugs, where pesticides were disrupting the food chain and silencing all birdsong. Back then, the public had no idea of the damage caused by habitat conversion and monocultural farming practices — almost 60 years later, thanks to the role played by Silent Spring in igniting the environmental movement, we know that pesticides are directly implicated in our current insect apocalypse.

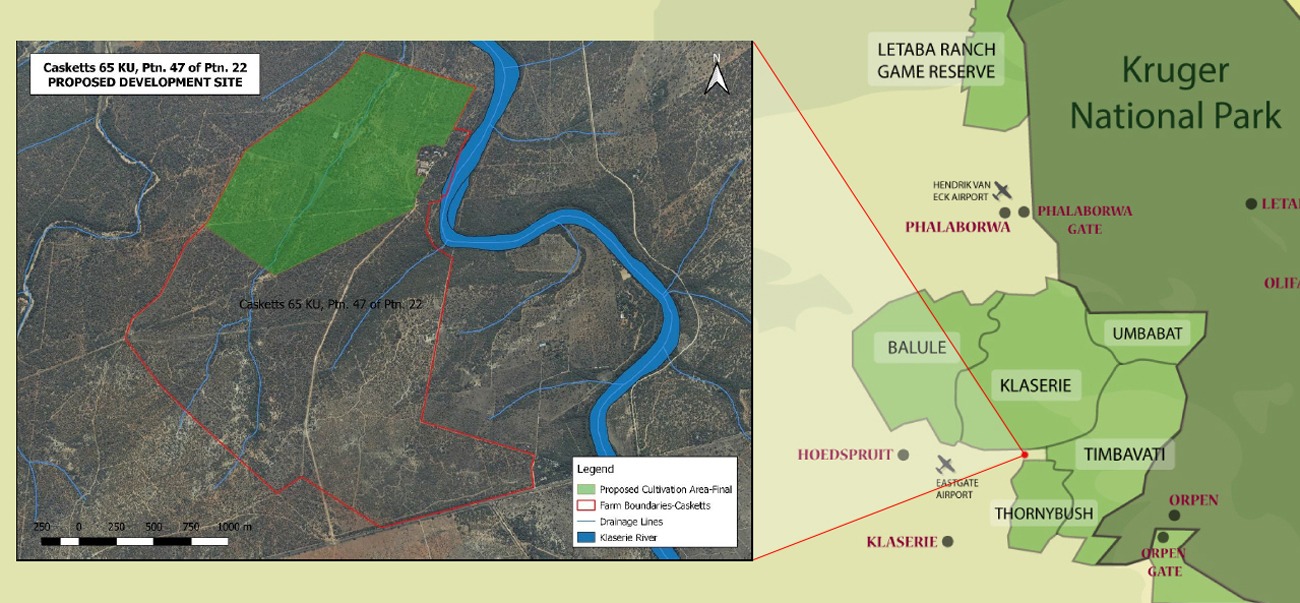

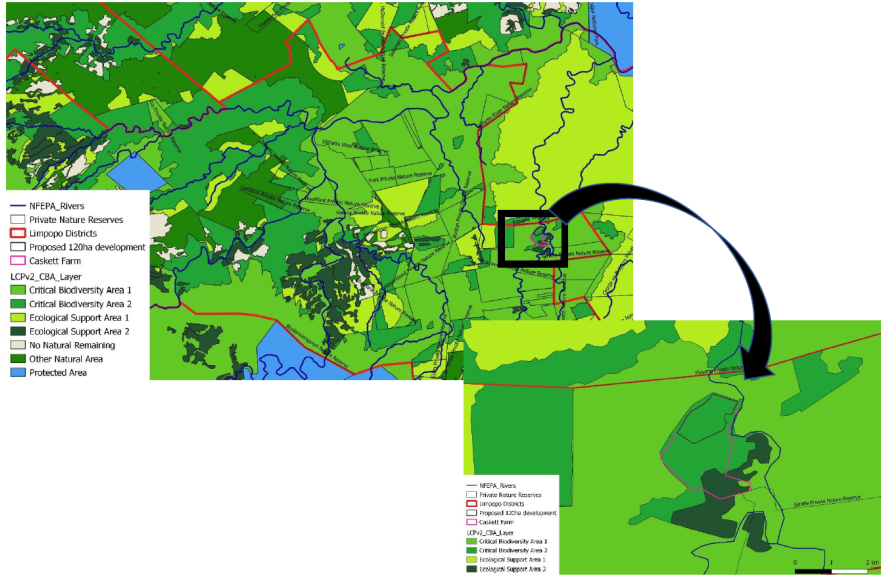

Of course, to every type of global ecological crisis there is a profusion of local contexts. On the Klaserie River, as Wilmot pointed out in her report, that context had everything to do with where the citrus farm had been staked out.

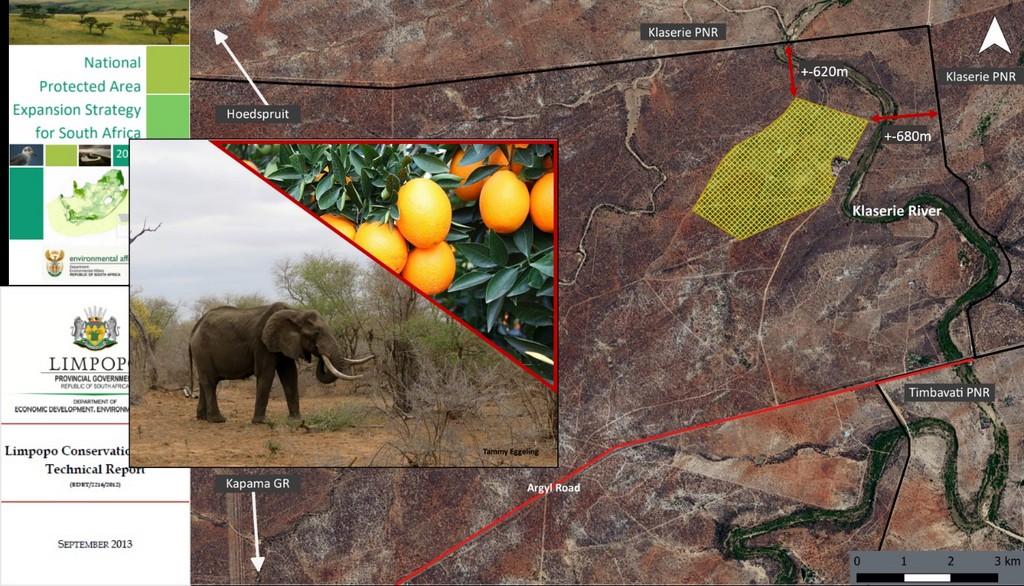

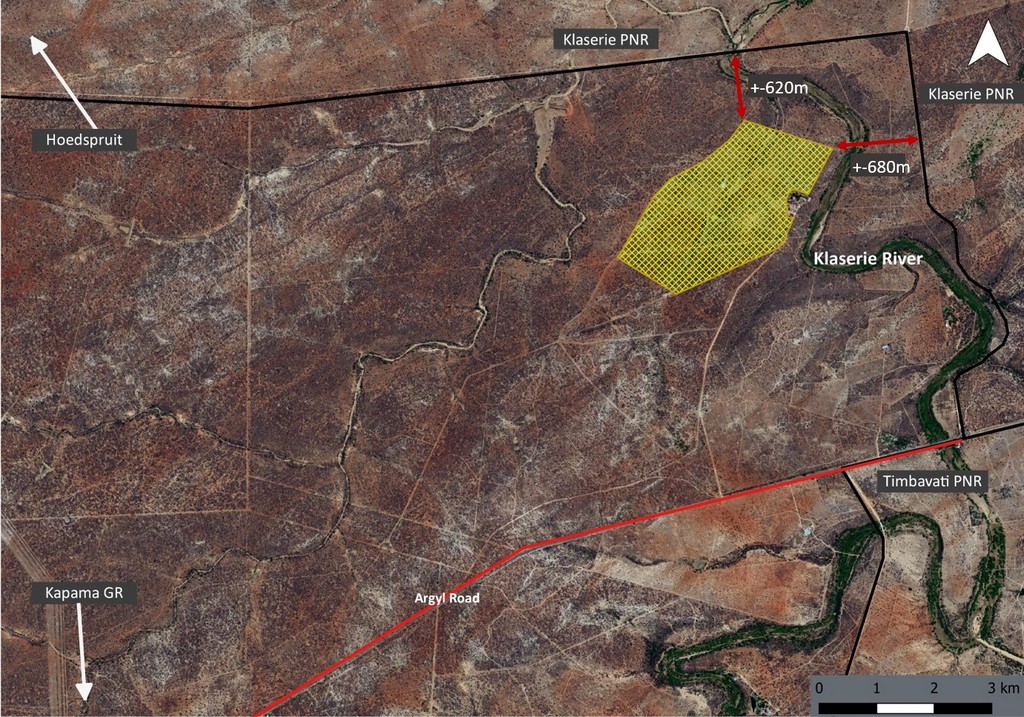

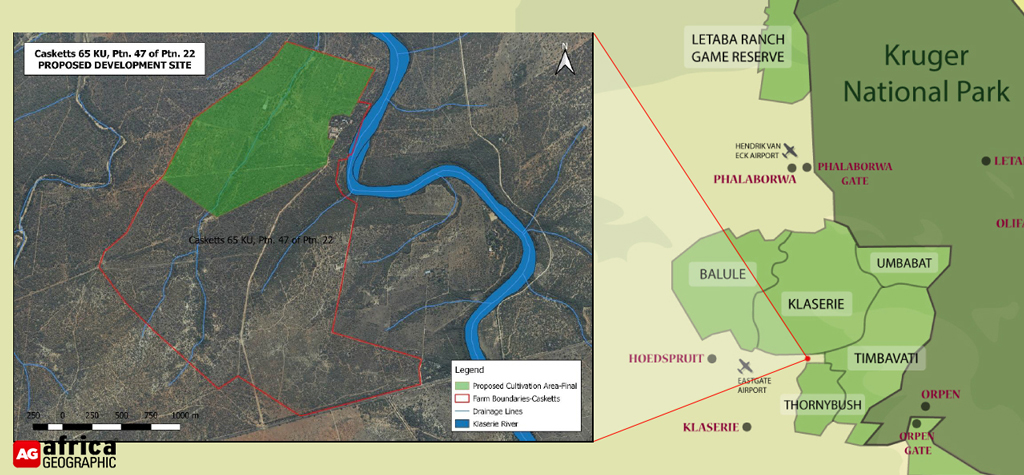

“The property occurs in an area where the main land use is either wildlife-based tourism or wildlife economy initiatives,” she wrote, before noting that it was sandwiched between two of the largest private game parks in the country — the 60,000-hectare Klaserie Reserve and the 53,000-hectare Timbavati Reserve.

Wilmot, who published her report in April 2019 on behalf of the NGO Elephants Alive, came to the fight when she realised that the elephants on these two reserves would almost certainly sniff out the orange orchards, which would result in “human-wildlife conflict” and the possible slaughter of the animals.

The Kruger National Park and the Kruger to Canyons Biosphere Region, in a response to the mooted project published five months earlier, had likewise foreseen the problem.

“The current fencing system ‘keeping animals in’ is very porous,” these conservation heavyweights had noted, “due to the fact that the Klaserie River itself cannot be fully fenced, meaning movement levels from the reserve to the proposed citrus area could be high.”

There were a number of reasons for their interest. First, as they had stressed, the proposed development was located inside the Kruger National Park Land Use Buffer, which had been “earmarked for expansion”.

In anticipation of the proclamation of the UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity of January 2020 — an international gathering that would call for a third of the surface of the earth to be “under protection” by 2030 — the response had explained that the property was slap-bang in the middle of the Greater Kruger Open System in South Africa — a vast wildlife corridor that (all things being equal) would eventually connect to the Greater Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area, as run trilaterally by South Africa, Zimbabwe and Mozambique.

Second, there was the fact that the Klaserie River flows into the Olifants River, one of the Kruger Park’s largest watercourses. Here, given the use of pesticides and herbicides that commercial citrus farming typically entails, the response had been pretty blunt:

“Vast amounts are being invested in the clearing of the Klaserie headwaters of invasive alien plants so as to improve streamflow. This additional water is not for uptake by a single entity, but is intended to maintain basic human needs and river health to the confluence. Downstream impacts on the protected areas are likely and there is little evidence of mitigation.”

The mitigation plans, as both Elephants Alive and the Kruger Park made clear, should ideally have been included in the draft environmental impact assessment, completed in 2018. As it turned out, the final EIA, submitted in June 2019, would acknowledge the likelihood that water use for irrigation of the citrus orchard would have a “negative impact on available water resources in the region”.

So how, then, did the citrus farmer get his environmental authorisation?

This question, among many others, would form the basis of ongoing litigation between the citrus farming company, identified in court papers as Casketts Sitrus (Pty) Ltd — a cosmetic name-change from Soleil Mashishimale (Pty) Ltd, a subsidiary of the Soleil Sitrus Group, which exports to markets in Europe, Japan, the Middle East and Russia — and the Klaserie Reserve, the Timbavati Reserve and Elephants Alive.

As the leading conservationists in the fight, these three applicants would lean on the tenets of the National Environmental Management Act (NEMA) to take Soleil’s environmental authorisation on review, a process — still pending at the time of this writing — that would involve hauling the Limpopo provincial authorities before the Polokwane High Court. But, given what they say is Soleil’s alleged manipulation of the provincial authorities’ ineptitude, they would also seek an urgent interdict to halt the farming conglomerate in its tracks.

Backing up the applicants, as “interested and affected parties” in a concurrent appeal process, would be no less than 12 of the biggest brands in South African conservation, including SANParks and the Greater Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area, with the Global White Lion Protection Trust offering support from the sidelines.

As all of them were aware, there was evidence to suggest that Soleil had acted unlawfully in its haste to plant saplings and get the operation going. By all accounts, once the trees were bearing fruit, it wouldn’t be long until there was a queue of farmers waiting to cultivate the Kruger Park buffer zone.

***

On 2 August 2019, the chief director of environmental trade and protection at the Limpopo provincial government’s department of economic development, environment and tourism (LEDET), which has featured heavily (and not entirely favourably) in Daily Maverick’s coverage of the Musina-Makhado SEZ — granted Soleil the right to start preparing the ground.

There were a number of caveats to the environmental authorisation, including the conditions that no more than 102 hectares would be open to cultivation; that a permit for removing “protected trees” would need to be obtained from the national department, and that no farming could take place within the flood line of the Klaserie River.

A month later, on 3 September 2019, the Limpopo MEC for economic development, environment and tourism, Thabo Mokone, was bombarded with all of 15 separate appeals against LEDET’s decision, as per the provisions of section 43 of NEMA. The appeal of Elephants Alive was submitted with a petition that had garnered 1,137 signatures.

From the perspective of the appellants, this was when the authorities began to reveal their “strangely disinterested” hand. For starters, they alleged, “despite repeated correspondence”, Mokone failed to adhere to the prescribed time limits for the processing of appeals.

Of way more concern, however, was the fact that Soleil — in apparent contravention of sections 43(7) and 49A(1) of NEMA, which jointly state that an appeal “suspends an environmental authorisation” and that to “commence with an activity” in these circumstance is a criminal offence — had in the interim brought in earth-moving equipment.

Still, as the appellants were about to discover, Soleil was just beginning to get warmed up. On top of the company’s disregard for the process, which it justified in legal correspondence (see below details of a letter) by suggesting that the MEC’s delay was evidence of his intention to deny the appeal, it would soon appear likely to them that the conditions of the original authorisation had been breached.

Although Soleil had been granted permission to repair one of the dam walls on the property, Google Earth satellite imagery — captured by Wilmot in February and August 2020 — seemed to suggest that the company had deepened and widened the dam itself.

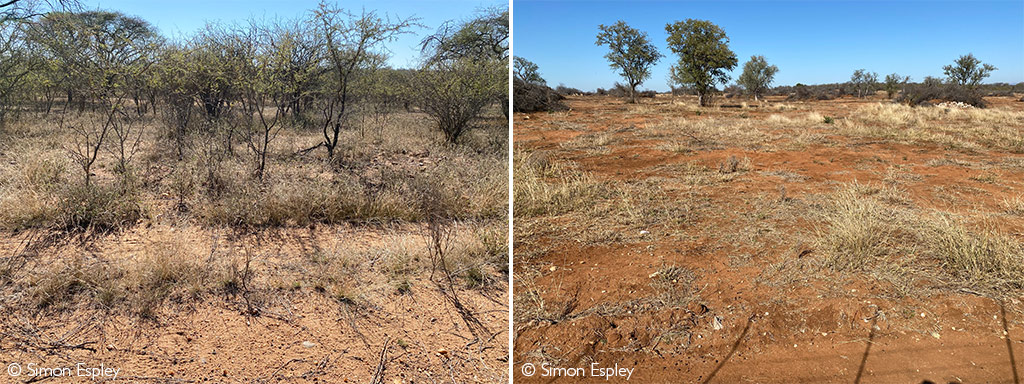

By October 2020, when the appellants managed to obtain a series of ground-level photographs, the full extent of Soleil’s activities had shifted to a realm beyond doubt. These images, shared with Daily Maverick, showed Caterpillar bulldozers, backhoe loaders and articulated trucks. In one image, a compactor was flattening a road; behind the machine, uprooted indigenous trees were lying in the rubble.

Caterpillar earth-moving machinery on Casketts Sitrus property. (Photo: Supplied)

Caterpillar earth-moving machinery on Casketts Sitrus property. (Photo: Supplied)

At which point, the appellants made the decision to call Mokone to account. On 19 November 2020, in a letter to the MEC on behalf of Elephants Alive — and copied to the Klaserie Reserve, the Timbavati Reserve, SANParks, Kruger2Canyons and the Greater Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area — attorney Richard Summers alleged that Soleil had transgressed NEMA and committed a criminal offence. Given that it was now more than 14 months since the appeal had been lodged, Summers demanded that LEDET, “as the competent authority charged with administering compliance”, investigate the case.

When nothing happened, Wilmot took a bash at raising the interest of some of the other public institutions in South Africa that are mandated with the investigation and prosecution of environmental crimes.

In late December 2020 and early January 2021, after unsuccessfully reporting Soleil’s alleged transgressions to the National Environmental Crimes and Incidents hotline, she lodged various complaints with the Environmental Management Inspectorate, otherwise known as the Green Scorpions, which were met with a disturbing silence. Her next port of call was the South African Police Service, which, as per section 31 of NEMA, has the same powers as the Green Scorpions — but again, crickets.

Meanwhile, the surveillance of Soleil’s activities continued.

On 15 December 2020, Bruce McDonald, a fixed-wing pilot who was working on behalf of anti-rhino poaching services in the area, buzzed the property. McDonald was able to capture images of the extensive land clearing that had been taking place.

In mid-February 2021, working off these images, Summers tried his own luck with the Green Scorpions, to no avail. A few days later, Wilmot herself was taking pictures from a light aircraft — the photographs, when collated with those from Wilmot’s second flight in April 2021, appeared to show breach of environmental legislation on a large scale.

Soil preparation was at an advanced stage, blue PVC irrigation piping was visible on the ground and an excavator was clearing vegetation in the property’s south-western corner, an area demarcated as a “no-go zone” by the environmental authorisation of August 2019.

By this late date, Wilmot and Summers were acutely aware that MEC Mokone — in fulfilment of Soleil’s prophecy — had denied the appeal.

A compactor flattens the road on Casketts property. (Photo: Supplied)

A compactor flattens the road on Casketts property. (Photo: Supplied)

The problem was, in the two-page decision of 24 March 2021, which had been rendered a full 18 months after the original submission, only the appeals of Klaserie Reserve and Masungulo Lodge were addressed. Neither Timbavati Reserve nor Elephants Alive, or any of the other conservation heavyweights involved in the matter, had received word of Mokone’s decision.

Also, the appeal decision had imposed one further condition on Soleil — that they “erect an elephant-proof fence around the property, in order to enhance the safety of freely roaming elephants and other damage causing animals”.

According to Wilmot, the images from the flyover of April 2021 showed that no such fence had been erected.

***

Like the conservationists, Soleil Sitrus had been heavily lawyered up from the start. Although Daily Maverick could not obtain the financial statements, it was obvious from the website that the company could afford to go toe-to-toe with the NGOs and game parks on every accusation — with 370 permanent employees, 500 seasonal employees and thousands of hectares under cultivation on 11 farms in multiple provinces, Soleil’s founder, Kobus van Staden, was clearly a man who was not fond of losing.

In a letter to Elephants Alive dated 10 September 2020, Soleil’s attorney, Leon Doyer of WdT Inc, noted that it had been more than a year since the conservationists had lodged their appeals. Referring to the National Appeal Regulations, Doyer pointed out that decisions on appeals were supposed to be a “speedy process”, allowing the authorities no more than 50 days from receipt of the responding statement.

“You are in charge of the current appeal,” Doyer insisted, in the correspondence with Elephants Alive. “Our client cannot verify that all the correct steps were taken to lodge the appeal timeously and procedurally correctly. It is obvious by now that [LEDET] either has taken the view that it is not obliged to even consider the appeal (due to some or other mistake in the process) or does not intend to do so.”

Accordingly, continued Doyer, “[our] client intends to proceed to act on the authorisation and commence with the development of the property for citrus farming”.

Six weeks later, however, after being informed that the appeal decision was expected on 27 November 2020 — and less than a week after Summers had requested Mokone to “investigate” the alleged criminal breach of NEMA — Doyer informed Summers, Mokone and LEDET that his client would “await the MEC’s final decision and then react accordingly”.

The Olifants River, Kruger National Park, South Africa. (Photo: Flickr / Manuel ROMARIS)

The Olifants River, Kruger National Park, South Africa. (Photo: Flickr / Manuel ROMARIS)

In light of the fact that a decision on just two of the 15 appeals was handed down on 24 March 2021, and given the ongoing “proof of development” that the appellants had gathered in the interim, Daily Maverick asked Van Staden whether he could provide a reasonable explanation for the contradiction.

Van Staden declined to engage, instead referring Daily Maverick to the court papers, so that we could “remain fully informed of proceedings”.

These papers, like Doyer’s legal correspondence, had been consistent in their framing of Soleil’s counter-arguments.

Where the conservationists argued that the property had lain fallow for a decade and thus retrieved its natural ecological state, Soleil argued that it was registered farmland, which hadn’t been pristine bushveld since 1967.

Where the conservationists contended that Soleil had breached their environmental authorisation by extending and deepening the dam, Soleil countered that they “were not developing the dam wall”, but “repairing the wall that already existed”.

Where the conservationists insisted that there was still no elephant-proof fence, Soleil maintained that “the fences currently in place” were “more than adequate deterrence against elephants”.

The dispute over water rights was another matter, one that Soleil — with apparent justification — claimed to have settled to the satisfaction of the authorities.

Here, Daily Maverick wanted to know — since Van Staden had co-signed the initial responding letter to the appeals with a certain Jurie Jansen van Vuuren, chair of the Klaserie Irrigation Board — whether he refuted the contention of the appellants that this represented a conflict of interest. Again, Van Staden chose not to engage.

As for the office of the MEC, the 18-month delay on the appeal decision was explained by “the involvement of multiple parties, the complexity of the matter as well as the lockdown”, with the MEC extending his “regrets and apologies” via LEDET head of department Solly Kgopong.

Daily Maverick was further informed that decisions had now been made on “all appeals”, although no explanation was offered — other than the fact that the matter was pending before the Polokwane High Court — for why the MEC had not investigated Soleil’s apparent breach of section 43 of NEMA.

As it happened, the “pending matter” was the judicial review that the Klaserie Reserve, the Timbavati Reserve and Elephants Alive had launched against Soleil’s original environmental authorisation, with the MEC and LEDET listed as co-respondents.

But on 14 May 2021, aware that they were losing ground with each passing day, these same applicants had approached the court for an urgent interdict, hoping to stop Soleil from “further clearing the land, installing irrigation systems, planting citrus saplings and erecting fences” until the decision on the review had been handed down.

On 8 June 2021, the interdict was denied — Judge Veronica Semenya, who had just one day to rule on the hundreds of pages in the court record, chose to set aside the ecological arguments and focus on the ineptitude of the authorities.

The applicants had been aware for some time that they “weren’t being assisted”, she noted in her ruling, “so why was the application only launched now?”

Still, in the face of what was looking more and more like a Kafka novel, the conservationists weren’t about to give up. The review application had been drawn up to go at the heart of the fight, where the ultimate arbiter would hopefully be NEMA itself.

Among the reasons for challenging the environmental authorisation was its failure to consider key policy documents — including the Kruger National Park Management Plan, the National Protected Areas Expansion Strategy and the Convention on Biological Diversity — and the allegation, argued at length with reference to NEMA, that it did not adequately assess “the cumulative impact on water resources”.

The review, when it happens, will see the Klaserie Reserve, the Timbavati Reserve and Elephants Alive up against Soleil Sitrus for what is likely to be the last time.

With SANParks and the rest of the “interested and affected parties” watching closely, the outcome won’t be limited to the region around Hoedspruit.

As Deon Huysamer, the chairperson of the Klaserie Reserve, told Daily Maverick, “it will set a very dangerous precedent if we allow the development to continue unchallenged.”

Just like Rachel Carson’s environmental science book, Silent Spring, it appeared Huysamer was considering the knock-on effects for the entire nation’s natural heritage. DM