Over the past 25 years, lion numbers have decreased by 43% throughout Africa, as their range has declined by more than 90%.

Prof. Dr. Hans Bauer

Research fellow: Northern Lion Conservation, University of Oxford

Over the past 25 years, I have spent a lot of time counting lions as part of my job. Only last month, I spent three hours with two males – possibly brothers – right next to my car in Maze National Park, Ethiopia. Lions come in the night, very quietly. Despite weighing well over 20 stone (around 150kg), you do not hear their footsteps. What you hear is their breathing, the turbo of the killing machine.

Had I turned on a light immediately, they would have run away. These lions are skittish, even if they face no threat from trophy hunters in Africa’s national parks. So we spend half an hour in the pitch dark before I finally switch on a small red light to count the eye reflections. Another pause, then a bigger red light enables us to see their sex and age.

We get lucky: with the big spotlight they move to a discrete distance, but we still get to watch them for an hour before retiring to our tents a few hundred metres away. The lions have long lost interest in us but the ranger makes a campfire which smoulders all night, just to be safe. This park has no outposts, no visitors and no emergency services, so we need to stay out of trouble.

Assisting with translocating a livestock-raiding lion to Waza National Park, Cameroon. Author provided

Maybe you have counted lions in a zoo or wildlife park: “I see three – no wait, there’s a tip of another tail and a flickering ear, so four, or five?” People on safari in popular destinations where lions are habituated to cars may have had the same experience. In the wilderness, however, lions are hard to spot – across much of their range you don’t see them very often at all, especially during the day.

I have spent countless nights sitting on top of my vehicle, playing buffalo or warthog cries with a megaphone, trying to catch a glimpse of lions attracted by these sounds. I have walked for days to find footprints or put up automated camera traps. For every day of fieldwork there is a day of grant writing before and a day of reporting afterwards – but yes, it is a wonderful job.

I once found lions in a part of Ethiopia where they had not been documented and added a blob on the distribution map. Unfortunately, over the last 25 years, it has been much more common to reduce or delete entries from our African Lion Database.

My research shows that during this time, lion numbers have decreased by 43% throughout Africa, and that their range has declined by more than 90%. There are now roughly 25,000 lions in 60 separate population groups, half of which consist of less than 100 lions. Their existence is particularly threatened across West, Central and East Africa.

I first went to Cameroon in 1992 to do my masters project in Waza National Park, and have worked in various parts of Africa ever since (I currently live in Mali). My main research focus with WildCRU – Europe’s first university-based conservation research unit – is the mitigation of human-lion conflicts. I study the difficult balance between people’s livelihoods and the conservation of biodiversity, working close-up at village level but also at national and international perspectives.

This led to me being asked to give evidence to the UK’s All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Banning Trophy Hunting, which on 29 June 2022 presented its report on the impacts of trophy hunting to the environment secretary, George Eustice. This follows the UK government’s announcement in December 2021 that it would ban the importing of body parts of 7,000 species including lions, rhinos, elephants and polar bears. On average, roughly ten lion “trophies” are imported into the UK each year, among many other threatened species.

There are many ways to look at this issue, and the debate usually ends up in a deadlock between utilitarians and moralists. I won’t hide my sympathy for the latter – I work with organisations such as the Born Free Foundation. But after a week in the field living on pasta and tinned tomato sauce, I will eat bushmeat in a village with no alternatives if it has been harvested legally and sustainably.

The future of trophy hunting in Africa was not on the table during the APPG’s discussions about a UK import ban – and if it was, it would be for African scientists to advise their governments of the pros and cons. In my view, however, the evidence is clear that trophy hunting has not delivered for wildlife in most parts of Africa, and that local communities benefit next to nothing from its continued practice.

How trophy hunting works

Trophy hunting is a controversial topic in conservation circles. In some cases, the fact that lions are doing better in parts of southern Africa has – wrongly, in my view – been attributed to it. But in itself, trophy hunting is not the lions’ biggest threat either; my research shows that more are killed when they attack livestock, or perish when their habitat and prey is diminished by agricultural encroachment or poaching.

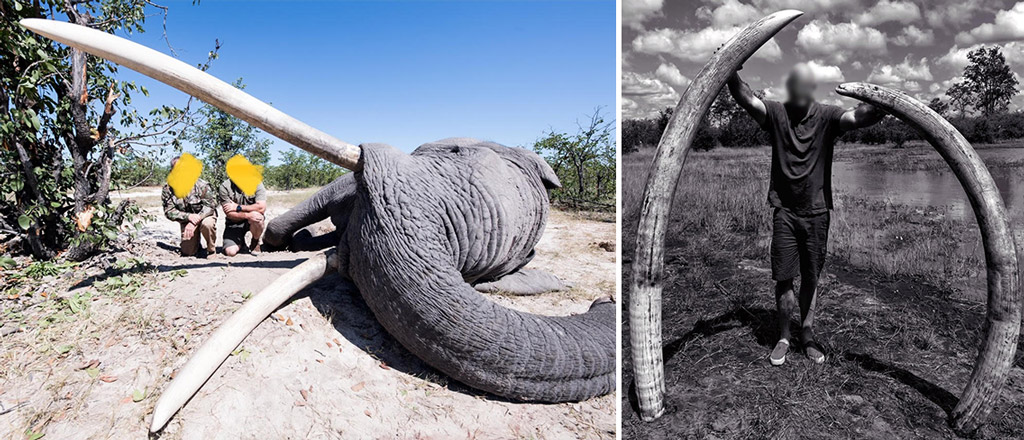

In Africa, trophy hunting’s popularity grew during colonial times when all sorts of slain animals were sent back to Europe. Nowadays, antelopes are this industry’s most hunted animals – but the most prestigious targets remain the “big five”: lion, leopard, elephant, rhinoceros and buffalo.

Lion image from a camera trap in Dinder National Park, Sudan. Author provided

A client might pay a local entrepreneur or hunting guide anywhere between £10,000 and £100,000 for a “bag” that includes a lion – and the super-rich may pay (or donate) even more. It’s a lot of money for a holiday, and trophy hunting mostly attracts rich, white, middle-aged men from western countries.

Hunting guides are businessmen (almost all are male). They generally lease government land that has been designated for conservation through “sustainable use”. Known as trophy hunting “blocks”, these areas vary widely (anywhere between 500km² and 5,000km²) and each has annual quotas for the amounts of different species that may be shot by trophy hunters.

In theory, this restricts the killings to a level the population can sustain. Hunting guides then manage their blocks to maintain these wildlife numbers, including organising anti-poaching patrols. The guides employ staff, pay the land lease, trophy fees and a bunch of other costs – including to a taxidermist and export company to deliver the skin and skull to their client after the kill. It is a big industry that claims to be good for both wildlife and local people, but these guides are not charity workers; they maximise their benefits and minimise their costs.

Trophy hunting also does not focus (as is sometimes suggested) on killing off the older, weaker animals in any block. Wildlife populations grow fastest when their densities are low, so that food and aggression are not limiting factors. In order to minimise any such competition – and to offer the biggest trophies – trophy hunts will target healthy animals, not just the old and infirm.

Lions and livestock

The methodology used for setting trophy hunting quotas varies from country to country. Cameroon, for example, has traditionally had very high quotas for lions, but these were not based on scientific rigour. In 2015 we published our first survey results based on observations done by three teams tracking lions over a vast range.

Each team drove for thousands of kilometres across Cameroon, very slowly, always with two trackers stationed on the bonnet of each 4x4 looking for footprints. We got stuck, camped, waited for trophy hunters to depart before being allowed into a particular area, struggled to get diesel, tolerated the heat and the tsetse flies – it was all part of our daily routine following the lions.

Ultimately, we counted 250 lions, 316 leopards and 1,376 spotted hyenas. Cameroon does not offer a trophy hunting quota for leopards, and hyenas are not popular with hunters – but as a result of our count, the country’s annual lion quota was reduced from 30 to ten. Today this quota is still applied throughout northern Cameroon’s Bénoué ecosystem, which has 32 trophy hunting blocks in between its three national parks.

Of these 32 blocks, however, more than ten no longer have any resident lions. And when the blocks lose their lions, this also threatens those living in the national parks – as there is a big difference between having 250 lions spread across 30,000km² of contiguous habitat, or three isolated populations of 50 in parks of 3,000km² each.

Grazing livestock can be easy prey for lions at night. Author provided

When I visited Cameroon again in 2021, I observed cattle everywhere – which is not a good combination with lions. Many of these herds had come from neighbouring countries – pastoralists running from the threat of terrorists in Mali and Niger. As a result, the pressure on these areas, and those who manage them, is intense. It is hard enough to integrate local communities in conservation work, much harder with nomadic people.

Whenever livestock grazes in an area with lions, you inevitably get some depredation. Lions will kill some livestock and, in retaliation, people will kill some lions. This is perhaps the biggest challenge in lion conservation, and all the programmes I know are working to mitigate it. There are tools available to reduce the damage, from flashlights and watchdogs to mobile enclosures and more. But this only works if you know the people living there and can collaborate towards a common goal – not if you have different people passing through every time.

In fact, the pastoralists I have met are usually quite tolerant – they like lions. A herder in Cameroon once told me: “If a lion attacks one cow this year, I will know that God has not forgotten me.” Another in Ethiopia said: “We do not think lions take our livestock to hurt us. As a result, we do not refer to it as an ‘attack’ or ‘killing’ – they are taking what they need.”

Nonetheless, some people – pastoralists and others – inevitably pay a high price for co-existing with lions, and they would prefer them in someone else’s backyard.

I have collared lions in several countries. I know the thrill of a hunt, but a dart gun does not kill – and the information you get from a lion’s collar is amazing. In Waza National Park, I followed lions this way and some behaved very well – but the worst offender killed a hundred-thousand dollars’ worth of cattle in our time there. The park’s warden asked me: “How long do you think the local people will pay this price for lion conservation?”

Almost all lion trophy hunting zones in Africa are part of larger ecosystems that include national parks, and in most cases the hunt quotas are based on the entire population of lions, including those living in the parks. An argument used by trophy hunters is that they are protecting extra land with extra lions – but it’s not that simple.

While trophy hunting blocks do add lions and extra habitat, they can still become a drain on the overall population when lions move out of the parks into emptied territories within the blocks. These so-called “source-sink dynamics” became a global news story in July 2015 because of Cecil, the black-maned lion that my WildCRU colleagues were satellite-tracking when he was killed by an American trophy hunter.

Cecil had been lured from Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe and was shot by Walter Palmer, a dentist from the Minneapolis area. It was actually quite a routine occurrence, but the death of Cecil the Lion created a worldwide media storm – feeding into the UK’s proposal for a ban on trophy hunt imports.

The model starts to unravel

Throughout most of Africa, lion numbers are declining. While trophy hunting is far from the only reason for this, the evidence clearly shows it has failed in its promise to provide a significant boost to wildlife conservation. I once thought it might offer benefits too, but studying its impacts and costs has taught me otherwise.

Trophy hunting is allowed in countries throughout East, Central and West Africa including Burkina Faso, Benin, Central African Republic, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Sudan and the Congo – and in all these countries, lion declines have been particularly steep. The Central African Republic is the most extreme example: almost half the country was designated as hunting blocks, yet wildlife there has all but disappeared. In 2012, the late researcher and conservationist Philippe Bouché published Game Over! – the title said it all.

A male lion in Zakouma National Park, Chad. Photograph: Chiara Fraticelli, Author provided

Trophy hunting has proved increasingly vulnerable to, on one hand, rising management costs due to the increased threats of agricultural encroachment and poaching (of both lions and their prey), and on the other, reduced income from smaller wildlife populations.

Two rules-of-thumb are widely used: a sustainable annual “harvest” is one lion per 2,000km², and the annual management of a trophy hunt block costs around US$1,000 per km² . Together, they suggest it costs around two million dollars to “produce a lion”. These numbers vary hugely between areas and, of course, trophy hunters shoot other species at the same time, but exceptional conditions are needed for the hunt companies to break even. At the same time, local communities living with wildlife are, understandably, demanding their fair share. The model starts to unravel and fall apart.

In Zambia and Tanzania, for example, 40% and 72% respectively of trophy hunting areas have been abandoned. Management costs are rising and private operators do not find it profitable any more, except in a handful of the best areas. This is not due to any outright ban but rather, the inability to balance of costs and benefits.

Across Africa, in the vast majority of cases, trophy hunting has not delivered more lions – whether because of financial imbalances, increased terrorism, land mismanagement or increased livestock mobility (or a combination of these factors). This failure to deliver undermines the already contested justification for the continued killing of lions by trophy hunters. And as the decline continues, many communities stand to lose a wildlife heritage that could, under a different approach to conservation, provide them with employment and stability.

Success stories?

Namibia and Botswana in southern Africa are often cited as models for conservation, which implies their experience could be replicated elsewhere. Trophy hunting has been presented as a success factor in these countries. But in reality, how instructive are the experiences of two large countries with a combined population of less than 5 million people for the other billion-plus Africans living in more densely populated areas?

Certainly, these two countries have a lot of wildlife – but is this due to the effects of trophy hunting, or to very low human population densities, diversified tourism industries and well-resourced wildlife institutions? In Botswana, trophy hunting was banned from 2014 to 2020, but despite abundant polemicising from both pro- and anti-hunting advocacy groups, I’m not aware of any evidence of a significant impact on its national lion and elephant numbers. In short, Botswana’s conservation efforts will succeed with or without trophy hunting.

Lion numbers are holding up well in Botswana. Shutterstock

While southern Africa has, in general, been quite successful in keeping its wildlife species stable, this is also not always through natural processes. There has been a lot of habitat engineering and captive breeding, so that many of the animals you find in confined nature reserves are, in fact, bred and auctioned.

In South Africa, for example, around 8,000 lions live in captivity for the benefit of a small number of rich owners, having been bred like livestock. This model does nothing to improve habitat or biodiversity levels, nor does it support rural socio-economic development. The country’s overall trophy hunting quota is around five wild lions and 500 captive lions each year, and while the US banned trophy imports from South Africa in 2016, most imported lion trophies into the UK have been killed there.

Another issue for Africa as a whole is that biologists have flocked to southern Africa’s conservation hotspots such as the Okavango Delta in Botswana and Kruger National Park in South Africa, which possess good infrastructure and lots of wildlife. As a result, there is an over-representation of people who have worked there among Africa’s community of conservation science, advocacy and practice. Many may never have worked outside southern Africa, and may not be aware of what is happening in the rest of the continent.

I’m not denying that some countries have been successful in their conservation efforts, and that trophy hunting has, in isolated cases, been part of that success. But the “if it pays, it stays” approach which seems to underpin many arguments in favour of trophy hunting has much more often led to the loss of natural ecosystems. This decay affects the vast majority of lion ranges, and an even greater majority of African citizens.

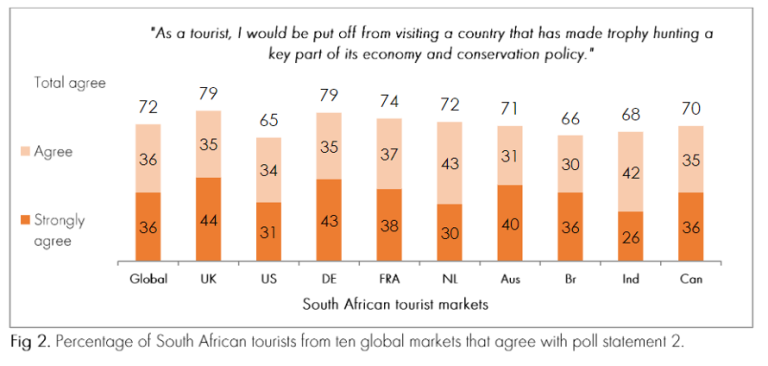

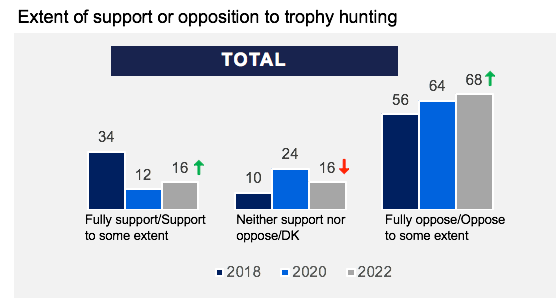

The banning of trophy hunt imports in the UK and elsewhere can, I believe, help to reduce or even reverse this decline. The UK ban is supported by a large majority of British voters. France, the Netherlands and Australia have already banned lion trophy imports, and the EU and US have restricted their imports. Since most clients want their trophy, that means significantly fewer potential clients overall, indirectly affecting Africa’s policy options.

The way forward

Throughout the continent, most policymakers stick to the prevailing narrative that trophy hunting supports conservation. In this way, a small white elite continues to have exclusive access to conservation areas that are off-limits for the average citizen to visit, or for public agencies to invest in. Trophy hunting is getting in the way of much-needed innovation and investment.

I agree with trophy hunters that the land they use is important habitat for lions and their prey. No one wants these areas to spiral down. However, the current situation feels like that famous frog in boiling water story – countries in Africa are afraid to jump out until they no longer can.

Hans Bauer assisting authorities to move a confiscated lion cub in Ethiopia. Photograph: Aziz Ahmed. Author provided

The largest and most important conservation area in West Africa is the 25,000km² W-Arly-Pendjari (WAP) region, on the boundary between Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger. With around 400 lions, it is the only three-digit lion population in West Africa, and it also possesses the largest West African populations of elephant and buffalo.

Half of WAP’s land is managed for trophy hunting. Yet over 20 years, these blocks have contributed less than 1% of the region’s total conservation budget. Much of the area is now increasingly threatened by terrorist incursions and large parts have been abandoned, including the hunting blocks.

In Benin, however, the situation is changing. Lion trophy hunting has been ditched and a trust fund established that promises to fund the country’s conservation activities in perpetuity. While mainly funded by Benin and German government agencies, the fund has an independent international structure and several other donors have contributed. The park’s management, now delegated to a non-profit organisation, is striving to improve local livelihoods by generating employment and offering support for community initiatives that do not harm the local wildlife.

Of course, we should not expect wildlife to fix poverty and instability where 50 years of development work have been unsuccessful. But I visit Benin every year and where I used to find a dozen friendly but unorganised staff, I now see hundreds of local people trained, employed and proud. In the past, some children might have gone to school reluctant to learn things they would not need as subsistence farmers. After visiting the park, however, I see signs that they want to learn skills and compete for career options their parents did not have.

Another glimpse of a better future can be seen in Akagera National Park, Rwanda, which was completely depleted in the 1980s and 1990s. Rwanda is the only country in Africa with a population density higher than India’s. It is a country facing a huge number of challenges, yet Akagera is a conservation success story. Following an initial investment in the area’s recovery, it is now breaking even through ecotourism with primarily Rwandan visitors. While this cannot be expected to work everywhere, it has worked in this most unlikely of places.

The true cost of saving African lions, and their prey and habitats, is estimated to be around US$1billion per year. With such funding, Africa could quadruple its lion numbers up to 100,000 without creating any new protected areas. At the moment, lions exist at only about a quarter of their ranges’ full capacities. Funding and community engagement are both critical to increasing this figure.

Ultimately, international solidarity is a much more substantial, and sustainable, source of funding than trophy hunting. Our approach to the extinction crisis should be similar to the one for climate: biodiversity justice as well as climate justice. The 2021 COP26 climate summit in Glasgow discussed the proposed annual fund of US$100 billion to help less wealthy nations adapt to climate change and mitigate further rises in temperature. A similar fund for supporting global biodiversity will be proposed at the COP15 summit in Montreal in December 2023. A billion dollars for Africa’s lions and other wildlife may sound unrealistic, but in the arena of international policy, it should not really be a problem.

African nations are sovereign, and hold the key to the future of the lion. Some may be keen to retain trophy hunting – but they know that demand is shrinking as UK politicians are the latest to respond to the concerns of their constituents.

Above all, the trophy hunting debate is divisive, draining energy from conservationists in Africa and around the world who agree on most other issues. Now is surely the time to focus our efforts on far better alternatives for the conservation of lions and other endangered species.

Remember those two lions in Maze National Park? They are part of a small population which has the park as its core area, but which roam the entire landscape in that part of southern Ethiopia. Sometimes a few lions make it across to the next park for some welcome genetic exchange. Maze’s head warden has lots of rangers to assist in monitoring them, but only one motorbike. There is no hotel for hours around, no fuel station, no media. He does not need trophy hunters, he needs a car.