Avian Feet

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5858

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5858

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

Re: Avian Feet

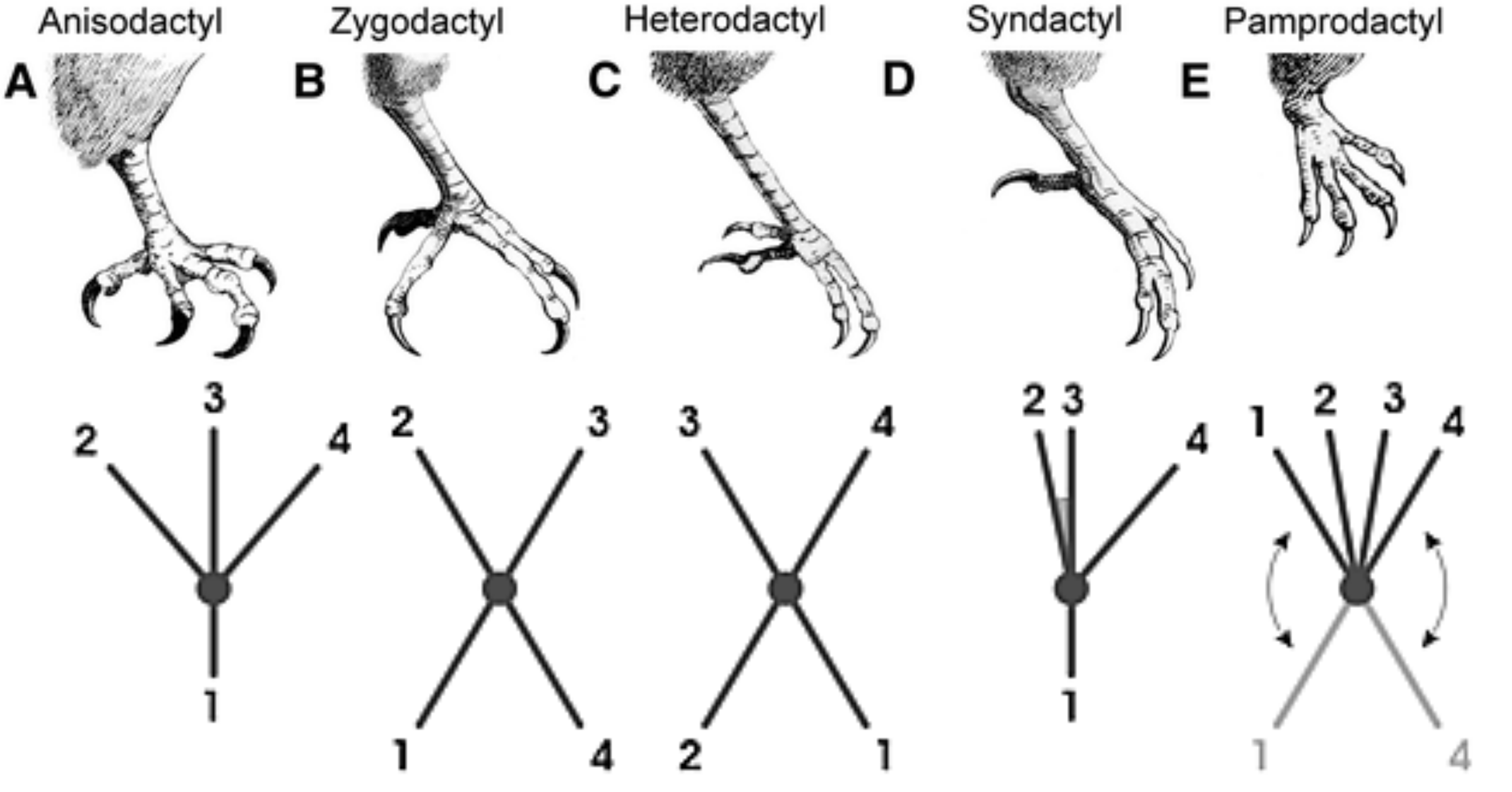

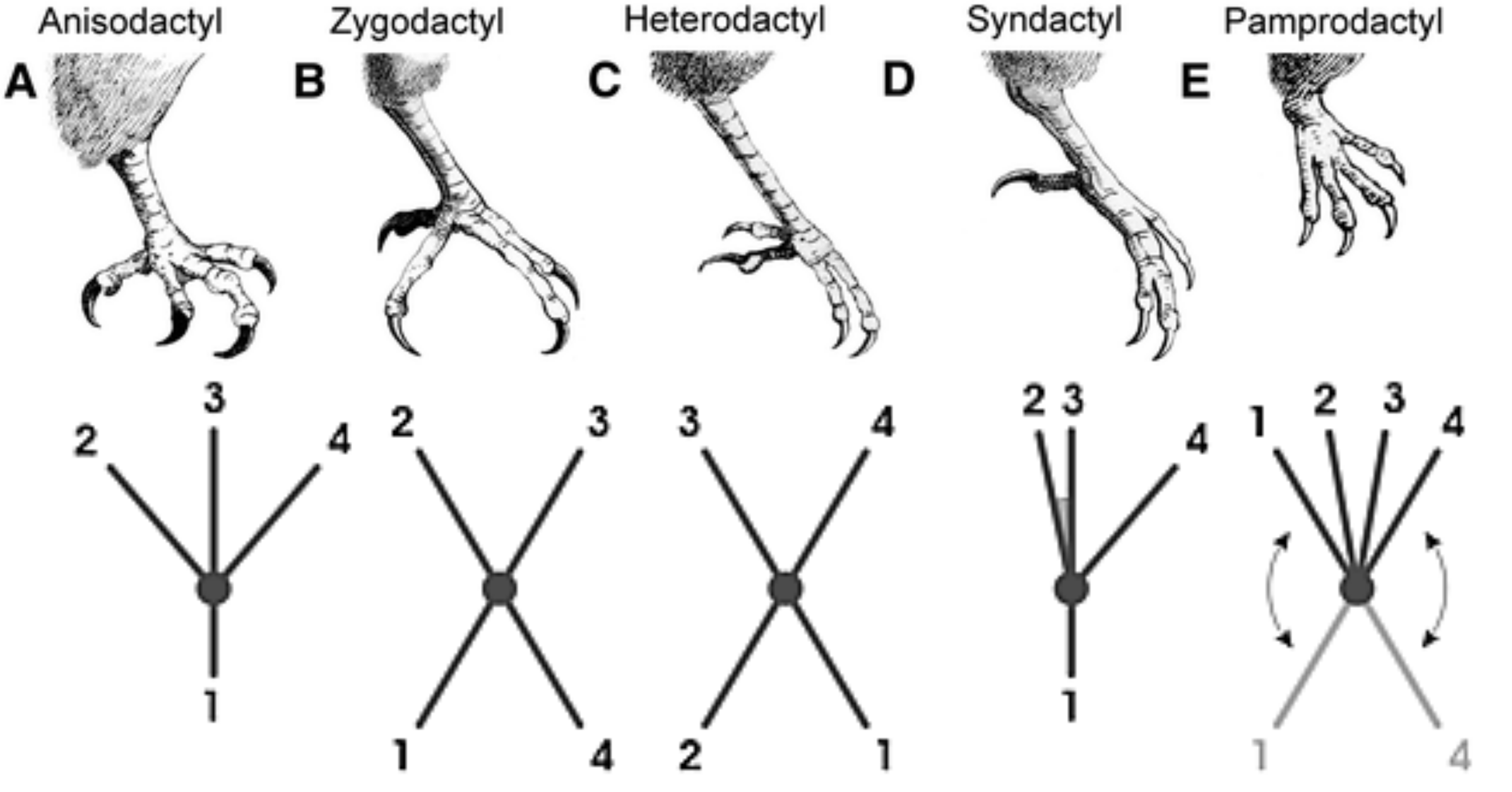

Biologists have named five general categories that describe the arrangement of birds’ toes:

anisodactyly,

zygodactyly (including semi-zygodactyly),

heterodactyly,

syndactyly and

pamprodactyly.

The first, and seemingly ancestral, configuration of birds’ toes – called anisodactyly – has three digits (numbered II, III and IV) orientated forwards and digit I (the ‘big toe’, or hallux) pointing backwards. This arrangement is the most common, being found in more than three-quarters of bird species, including the webbed feet of ducks and penguins, most songbirds (such as sparrows and weavers) and pigeons, buzzards, vultures, eagles and gamebirds.

The anisodactyl toe orientation is well suited to perching and grasping, especially when the halluxis elongated, but it is not the only evolutionary ‘solution’ to such activities.

In the second most common foot type among birds – called zygodactyly – digits II and III point forwards and digits I and IV point backwards. Some perching birds, such as cuckoos and turacos, have this arrangement, but it is also well suited to grasping, as in parrots, and climbing, as in

woodpeckers. These species are not closely related, which suggests that zygodactyly has evolved multiple times.

Trogons have a unique arrangement of digits – termed heterodactyly – which resembles zygodactyly except that digits III and IV point forwards and I and II backwards.

Some advantages to zygodactyly and heterodactyly might include increased grip strength for perching resulting from two pairs of toes opposing each other, and better grasping for similar reasons. Parrots, among other species, routinely manipulate their food using their feet – there are even left-footed and right-footed parrots.

Birds such as ospreys, owls, mousebirds and some woodpeckers have the ability to rotate the outer digit (IV) forwards and backwards – described as semi-zygodactyly or ectropodactyly.

There is another configuration – known as syndactyly – in which two or more toes (usually III and IV) are fused to varying degrees. In the

avian world, the fleshy sheath that unites the anterior digits is thought to increase grip strength when the bird is perching, as it forces the digits to act in concert.

Syndactyly is common among kingfishers, hornbills and beeeaters (Coraciiformes) and there are many intermediate examples of birds with partly fused toes in this group. Extreme syndactyly occurs in the wood-hoopoes and hornbills and diminishes progressively through the kingfishers to only minor fusion in Upupa and finally the true anisodactyl feet of rollers. Similarly, among passerines it can sometimes be difficult to distinguish the syndactyl and anisodactyl conditions, as they intergrade closely.

The final arrangement of toes – pamprodactyly – is found among some mousebirds and swifts, and is characterised by all four digits being directed forwards, enabling these species to hang their weight on all four toes and even feed upside-down.

anisodactyly,

zygodactyly (including semi-zygodactyly),

heterodactyly,

syndactyly and

pamprodactyly.

The first, and seemingly ancestral, configuration of birds’ toes – called anisodactyly – has three digits (numbered II, III and IV) orientated forwards and digit I (the ‘big toe’, or hallux) pointing backwards. This arrangement is the most common, being found in more than three-quarters of bird species, including the webbed feet of ducks and penguins, most songbirds (such as sparrows and weavers) and pigeons, buzzards, vultures, eagles and gamebirds.

The anisodactyl toe orientation is well suited to perching and grasping, especially when the halluxis elongated, but it is not the only evolutionary ‘solution’ to such activities.

In the second most common foot type among birds – called zygodactyly – digits II and III point forwards and digits I and IV point backwards. Some perching birds, such as cuckoos and turacos, have this arrangement, but it is also well suited to grasping, as in parrots, and climbing, as in

woodpeckers. These species are not closely related, which suggests that zygodactyly has evolved multiple times.

Trogons have a unique arrangement of digits – termed heterodactyly – which resembles zygodactyly except that digits III and IV point forwards and I and II backwards.

Some advantages to zygodactyly and heterodactyly might include increased grip strength for perching resulting from two pairs of toes opposing each other, and better grasping for similar reasons. Parrots, among other species, routinely manipulate their food using their feet – there are even left-footed and right-footed parrots.

Birds such as ospreys, owls, mousebirds and some woodpeckers have the ability to rotate the outer digit (IV) forwards and backwards – described as semi-zygodactyly or ectropodactyly.

There is another configuration – known as syndactyly – in which two or more toes (usually III and IV) are fused to varying degrees. In the

avian world, the fleshy sheath that unites the anterior digits is thought to increase grip strength when the bird is perching, as it forces the digits to act in concert.

Syndactyly is common among kingfishers, hornbills and beeeaters (Coraciiformes) and there are many intermediate examples of birds with partly fused toes in this group. Extreme syndactyly occurs in the wood-hoopoes and hornbills and diminishes progressively through the kingfishers to only minor fusion in Upupa and finally the true anisodactyl feet of rollers. Similarly, among passerines it can sometimes be difficult to distinguish the syndactyl and anisodactyl conditions, as they intergrade closely.

The final arrangement of toes – pamprodactyly – is found among some mousebirds and swifts, and is characterised by all four digits being directed forwards, enabling these species to hang their weight on all four toes and even feed upside-down.

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5858

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5858

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75408

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Avian Feet

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5858

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

Re: Avian Feet

Ostrich is the only bird that has a didactyl foot

Other birds have the dinosaur structure with 4 toes. Like most amphibians and birds today, theropod dinosaurs had four digits on each limb – in other words, were tetradactyl – whereas living reptiles (chameleons, lizards and geckos) most often have five.

Other birds have the dinosaur structure with 4 toes. Like most amphibians and birds today, theropod dinosaurs had four digits on each limb – in other words, were tetradactyl – whereas living reptiles (chameleons, lizards and geckos) most often have five.

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75408

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Avian Feet

Agreed!

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65942

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Avian Feet

And then there are the waders

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5858

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

Re: Avian Feet

The webbed feet of waterbirds are morphologically diverse and classified into four types: the palmate foot, semipalmate foot, totipalmate foot, and lobate foot. Waders (Charadriiformes) are anisodactyl with or without webbing between the toes.