Image: Pixabay

One of the most profound leaps human civilisation has made is to confess the enormity of what we do not know. We know, to a great extent, who and what we are and that, in the universe, we are almost nothing. It’s the official discomfort of such dramatic discoveries that has often seen the persecution of so many profound thinkers.

An astronomer was travelling in a rural area and, one evening, he crossed paths with a peasant woman. They greeted and fell into conversation.

“What is it that you do?” the woman asked him.

“I study all that,” he said, sweeping his arm across the glittering sky. “I try to figure out how Earth, stars and galaxies work.”

“Ah yes,” she replied. “I know how they work.”

He was surprised. “You do? Tell me.”

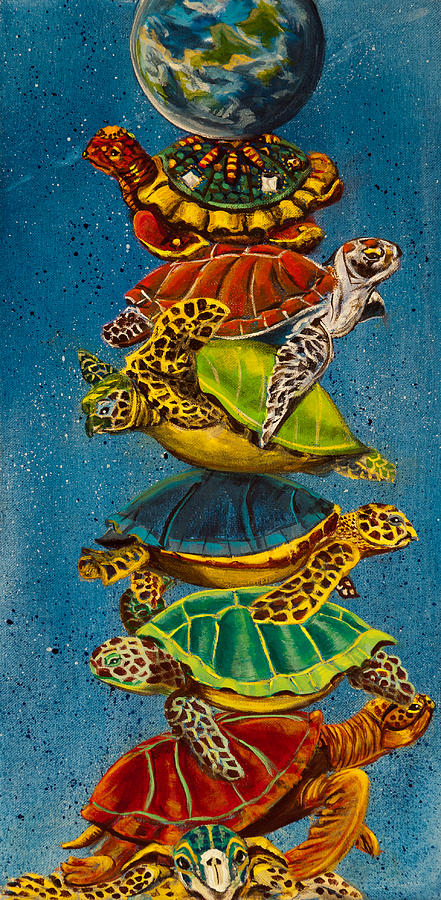

“Well, the Earth is a flat plate balanced on the back of an enormous turtle.”

“Oh yes?” he said, amused. “Well, can you tell me upon what the turtle is balanced?”

“Ah! Mr Astronomer,” she said, “you can’t catch me out. It’s turtles all the way down.”

Turtles All The Way Down is a painting by Susan Culver. Image: PIxels

What she thought she knew for certain was wrong. But he knew that what he knew was provisional.

One of the most profound leaps human civilisation has made is to confess the enormity of what we do not know. This gave birth – first in the Middle East, then in the Western world and spreading to most nations – to collective curiosity about the world in which we live. And central to that curiosity was the question: What if… ? It dared us to break orthodoxy.

When the philosopher Daniel Dennett was a schoolboy, he and some friends hit on the idea of universal acid. What if there was such a thing? It would be a liquid so corrosive that it would eat through anything – all the way down.

The problem would be how to contain it. It would eat through plastic, glass, stainless steel, ceramic or lead. Where would it end up? Could it eat all the way down to the centre of the Earth? What would be left?

A similar “what if” thought was used by the writer Kurt Vonnegut in his book Cat’s Cradle. In it, a fictional polymorph of water, Ice Nine, is invented. It melts at 45.8°C instead of 0°C and when it comes into contact with ordinary water, it acts as a seed that instantly crystallises it into frozen Ice Nine. The plot, of course, is to keep it out of the sea.

These substances, which fortunately don’t exist, utterly transform everything they touch. But there are things born of curiosity that do exist and have a similar effect.

In a deeply religious world dominated by the Vatican, Galileo Galilei ground lenses and produced a telescope that could magnify 30 times. Curiosity turned it heavenwards and through it, he observed the moons of Jupiter, the movement of the planets and the stars of the Milky Way. We were, he wrote, on a planet moving around the sun.

This could not be, said the Catholic Church. Psalm 93:1, 96:10 and 1 Chronicles 16:30 states that “the world is firmly established, it cannot be moved”. Ecclesiastes 1:5 notes that “the sun rises and sets and returns to its place”.

Galileo was found “vehemently suspect of heresy”, for having held opinions that “the Sun lies motionless at the centre of the universe, that the Earth is not at its centre and moves”. He had, furthermore, held and defended an opinion which had been declared contrary to Holy Scripture. He was required to “abjure, curse and detest” those opinions and was placed under house arrest until the day he died.

As we know, he was correct and his view, which prevailed, was to utterly dislodge humans and Earth as the centre of the universe. Albert Einstein was to call Galileo the father of modern science.

In 1859, the biologist Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in which he outlined the process of natural selection. The beginning of all species, he said, was other species. Humans, like all other creatures, evolved by beneficial chance mutation and survived because we were better suited to conditions than others who weren’t. Our nearest relatives weren’t angels but the great apes.

Like Galileo, Darwin wasn’t wrong. But the implications were explosive, not least for the Church’s belief in divine creation. As they saw it, natural selection displaced the need for God.

I’ll return to Darwin in a moment, but first, let’s look at another idea that upended our world. In 1953, researchers James Watson and Francis Crick, using X-ray diffraction data collected by Rosalind Franklin, discovered the structure of DNA, the core building block of all life. We were, it turned out, the product of small variations in the basic plan used by almost everything that lived, differing by a gene switch here and there. It was extremely humbling, though instead of being banished, they were given a Nobel Prize.

The line through Galileo, Darwin, Franklin, Crick and Watson has been one of human displacement. From semi-angels we have become mere inquisitive mammals on an insignificant planet circling a mediocre sun lost in a universe of unimaginable vastness and fighting to survive.

Image: Shutterstock

But let me return to Darwin, because the effect of his ideas, like universal acid or Ice Nine, threatens to leak out into areas we have not yet figured how to contain. We can cede to him some or all of modern biology. But why stop there? Let’s go all the way down with no turtles for support.

What if his idea is true for cosmology: our universe being merely the successful survivor of many previous universes? Is the Earth a single species among many different families of planets, likely to thrive or go extinct?

And we can also go all the way up. What’s the ethics of natural selection? What does survival of the fittest say of our psychology or religion? Do we really think, or are we thought by our biological imperative to survive?

Following the scientific revolution which Galileo, Darwin, Crick, Watson and others were central in bringing about, the genie is out of the lamp. Pandora’s box is open. The old, comforting stories no longer suffice.

We know, to a great extent, who and what we are and that, in the universe, we are almost nothing. It’s the official discomfort of such dramatic discoveries that has often seen the persecution of so many profound thinkers.

What they teach us, however, is not negative. It is that we have the potential to think beyond our personal and planetary boundaries because of one thing that makes us different from all that has come before. We are curious and can ask the question: “What if… ?” And answer it. We’re the first creature we know that can look at all existence with understanding. We can’t yet see all the way down, but we can see a very long way down – and it’s not a tower of turtles. If only for that, our curiosity has been worth it. DM/ML