Nasa turns its gaze from space to the Western and Eastern Cape in new biodiversity project

A new biodiversity research project, BioSCape, will link data collected from Nasa satellites and aeroplanes with field observations to better understand the biodiversity of the Greater Cape Floristic Region, impact of climate change on biodiversity, and nature’s contributions to people. (Photo: Shelley Christians)

By Kristin Engel | 26 Oct 2023

A new biodiversity research project, BioSCape, will link data collected from Nasa satellites and aeroplanes with field observations to better understand the biodiversity of the Greater Cape Floristic Region, impact of climate change on biodiversity, and nature’s contributions to people. (Photo: Shelley Christians)

By Kristin Engel | 26 Oct 2023

Two Nasa planes took flight from Cape Town last week as part of a project with South African scientists aimed at improving understanding of the impacts of climate change on biodiversity and to reduce biodiversity loss and threats.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

NASA technology used to study outer space is now being turned downwards towards the Western and Eastern Cape to scan one of the most unique biodiversity hotspots on the planet — the Greater Cape Floristic Region (GCFR), described as the most difficult place on Earth to study biodiversity.

The project — BioSCape — is a biodiversity survey conducted by the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Nasa) with several South African organisations to link satellite and airborne data with field observations to better understand the biodiversity of the GCFR and the impact of climate change on biodiversity. The project will explore the threats to biodiversity across terrestrial and aquatic systems in the region, as well as their structure, composition and function.

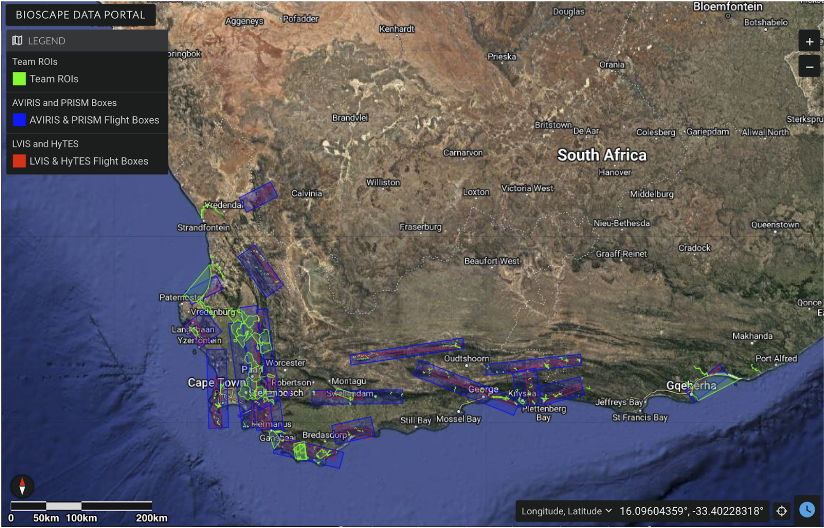

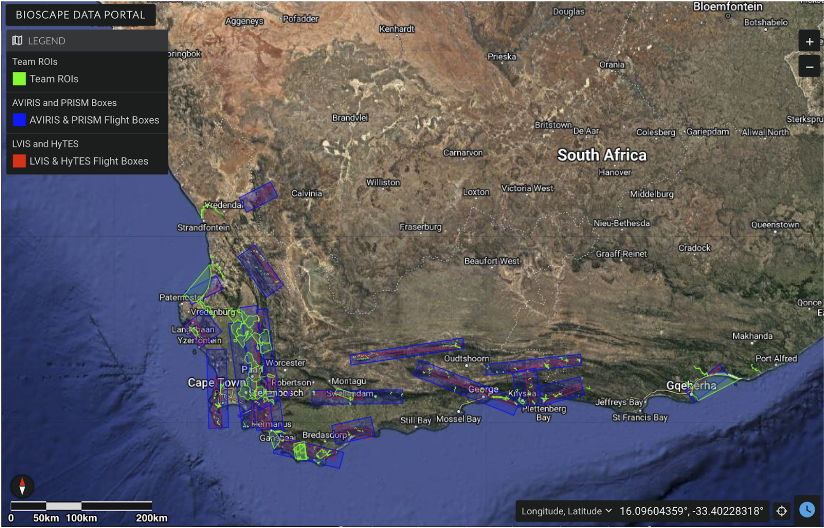

Last week, two modified Nasa planes — a Gulfstream III and a Gulfstream V — took off from Cape Town to begin six weeks of data collection across the GCFR for the one-of-a-kind project.

The area the Gulfstream III and Gulfstream V will scan. (Map: Supplied)

The area the Gulfstream III and Gulfstream V will scan. (Map: Supplied)

The project was at least eight years in the making by a joint team of about 150 South African and US scientists before the planes could take to the sky. Daily Maverick observed the first takeoff with the teams on Friday, 20 October.

The aim is to improve understanding of the impacts of climate change on biodiversity to develop new technologies for monitoring and managing nature’s contributions to people to reduce biodiversity loss and threats.

Woody Turner, programme scientist for Biological Diversity and programme manager for Ecological Forecasting at Nasa’s Science Mission Directorate, oversees Nasa’s research efforts to use satellite-derived information to understand the relationship of biodiversity to climate and landscape change and ecosystem function.

‘Our life-support system’

Turner told Daily Maverick that biodiversity underpins our lives and how we function as a species; it cleans the air, purifies water and provides an abundance of food, clothing material, materials we build from, medicines and so much more.

“That’s our life-support system,” Turner said. “I’d say climate change and biodiversity loss are two existential crises facing humanity today. Existential, because if we don’t fix it, if we don’t do it and get it right it can lead to our own demise, the extinction of species.

“People are very focused on climate. That’s great, but I’d say equally dire is the loss of biological diversity. This is something that may be harder for us to correct than our changing climate… Extinction is a one-way ticket, it’s a one-way loss. We can’t really fix that.”

Turner said climate change and biodiversity loss were intimately connected and just as life affected climate, climate affected life.

Scientists from South Africa and the United States have teamed up to study biodiversity in the Greater Cape Floristic Region. (Photo: Shelley Christians)

Scientists from South Africa and the United States have teamed up to study biodiversity in the Greater Cape Floristic Region. (Photo: Shelley Christians)

“I work for Nasa so yes, we’re trying to go to Mars and Mars is great, but living on Mars is not trivial. We evolved to live here [on Earth], so let’s take care of what we know and what we got, because this is our cradle, this is our home and where our children live. So we need to take care of it, but we can’t take care of it without understanding and taking care of the life around it,” he said.

BioSCape marine science lead Erin Hestir, from the University of California, added: “Nasa is most famous for studying space, and we all think about looking for life in other places, but the one place where we know life exists is here on planet Earth, and it’s precious because it literally defines our ability to be here. That diversity of life is what supports our livelihoods and makes planet Earth so special and unique.”

The science team consists of Jasper Slingsby, a senior lecturer in Plant Ecology and Global Change Biology at the University of Cape Town (UCT); Adam Wilson, BioScape terrestrial science lead from the University of Buffalo; Hestir; Anabelle Cardoso, BioScape science team manager from the University at Buffalo and UCT and Cherie Forbes, Applications Coordinator.

Cardoso has been a leading force in the project, coordinating all the researchers and ensuring that researchers in the field are in sync with the data collected from the aircraft.

“What’s really exciting about this project is that in a lot of ways the technology that NASA has come up with has outpaced the science, in the sense that the technology is extremely impressive and so far has been focused on looking at other planets, or like methane emissions, which are very important, but this is the first time that Nasa — or anyone really — is making a concerted effort to catch up biodiversity science with the potential of the technology,” Cardoso said.

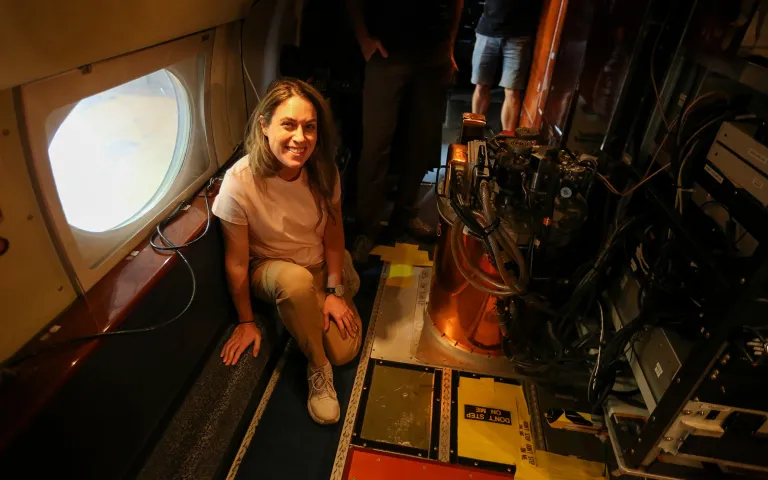

Cardoso explained that the sensors being used – imaging spectrometers -have been used for looking at planets but now they hope this technology could be useful for monitoring ecosystems on Earth.

“What NASA is trying to do is to eventually have these sensors on satellites, imaging the whole world at regular time intervals, and what they’re interested in, is seeing if these kinds of sensors on satellites can measure biodiversity, but this is not easy to do. So before they can get to this, they run airborne campaigns, which is where they take a very similar sensor and instead of putting it on a satellite, they put it on an aeroplane and then have the aeroplane fly over imaging the area. Then we are pairing this with ground observation by all of our field scientists who are out in the field,” she said.

Unique technology

BioSCape is studying coastal and marine environments in the GCFR using airborne imaging spectroscopy, lidar and new hyperspectral data, ranging from UV to thermal wavelengths.

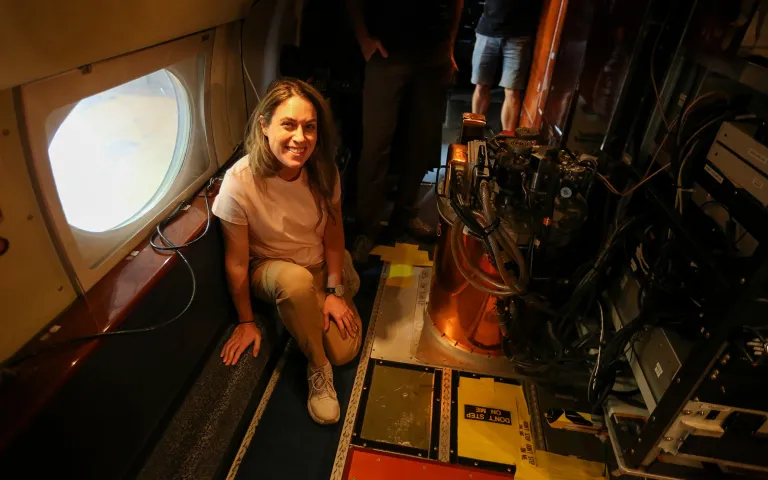

Holly Bender from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the team lead of the Portable Remote Imaging Spectrometer. Bender led the team that built this technology for the plane, which will use remote imaging to explore the marine and freshwater ecosystem distribution, structure and composition. The data for BioScape is being collected using a unique combination of four remote sensors built on the planes, each giving a different set of data. (Photo: Shelley Christians)

Holly Bender from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the team lead of the Portable Remote Imaging Spectrometer. Bender led the team that built this technology for the plane, which will use remote imaging to explore the marine and freshwater ecosystem distribution, structure and composition. The data for BioScape is being collected using a unique combination of four remote sensors built on the planes, each giving a different set of data. (Photo: Shelley Christians)

These remotely sensed data will combine with existing and new field observations of the spatial distribution of species, ecosystems and their characteristics. Together, these observations enable high-resolution mapping of biodiversity, functional traits and environmental variations and local disturbances (weather, human activity, land degradation, etc).

The data for BioSCape is collected using a unique combination of four remote sensors built into the two planes, each giving a different set of data that will be analysed to create the survey of the GCFR. This data will be available for all researchers once compiled and will assist with numerous research projects.

Biodiversity research project BioSCape will link data collected from Nasa satellites and aeroplanes with field observations to better understand the biodiversity of the Greater Cape Floristic Region, impact of climate change on biodiversity, and nature’s contributions to people. (Photo: Shelley Christians)

Biodiversity research project BioSCape will link data collected from Nasa satellites and aeroplanes with field observations to better understand the biodiversity of the Greater Cape Floristic Region, impact of climate change on biodiversity, and nature’s contributions to people. (Photo: Shelley Christians)

The four remote sensors are:

- AVIRIS-NG: The Airborne Visible / Infrared Imaging Spectrometer – Next Generation sensor studies interactions between climate and the health of vegetation and aquatic ecosystems. It is a whisk-broom imaging spectrometer with a spectral range of 380-2,510nm and sampling resolution of 5nm.

- HyTES: The Hyperspectral Thermal Emission Spectrometer sensor is a hyperspectral imaging spectrometer measuring thermal emission in the 7.5μm-12μm range. It provides ecosystem diversity metrics in terrestrial settings and physical marine measurements (eg, sea surface temperatures).

- LVIS: The Land, Vegetation, and Ice Sensor (LVIS) is a laser altimeter scanner able to produce 3-D images of topography and vegetation. Data from LVIS will be fused with spectral information from the above scanners to enhance biodiversity observation and prediction

- Prism: The Portable Remote Imaging Spectrometer sensor will explore marine and freshwater ecosystem distribution, structure and composition. It is a pushbroom imaging spectrometer with a spectral range from 350-1,050nm and two bands in the short wave infrared.

Holly Bender, from Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the team lead of Prism, explained that they had built the technology by hand for the two planes.

“So on the plane we have two imaging spectrometers, they look at different wavelengths of interest — one is more focused on aquatic and ocean target areas and one a little bit on terrestrial — but they’re both looking out from the bottom of the plane simultaneously. They’re both passive instruments, so we’re not shining any lights or anything like that. We’re looking at reflected sunlight.

From left, Jasper Slingsby, senior lecturer in Plant Ecology and Global Change Biology at UCT; Adam Wilson, BioScape terrestrial science lead from the University of Buffalo; Erin Hestir, BioScape marine science lead from the University of California, Merced; Anabelle Cardoso, BioScape science team manager from the University at Buffalo and University of Cape Town. (Photo: Shelley Christians)

From left, Jasper Slingsby, senior lecturer in Plant Ecology and Global Change Biology at UCT; Adam Wilson, BioScape terrestrial science lead from the University of Buffalo; Erin Hestir, BioScape marine science lead from the University of California, Merced; Anabelle Cardoso, BioScape science team manager from the University at Buffalo and University of Cape Town. (Photo: Shelley Christians)

“The sunlight will reflect off of whatever we’re flying over, and then we’re measuring. As we keep moving forward in the plane, we’re measuring more and more at a time,” she explained.

UCT’s Slingsby said their goals are to determine what can be done with this imagery and how useful it will be for mapping and monitoring biodiversity. If all goes according to plan, Slingsby said that the next step would be for Nasa to place the imaging sensors on satellites to provide regular imaging at a global scale.

“The goal is not just to track change, but also to highlight where we might need to intervene to improve conservation.”

South African research partners include the National Research Foundation, the South African Environmental Observation Network, the South African National Biodiversity Institute, South African National Parks and CapeNature.

The science team estimated that funding for the project consisted of about R220-million from the US and R11-million from South Africa. The official launch of the project will take place on 17 November. DM