Elephant Management and Poaching in African Countries

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65750

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Elephant Management and Poaching in African Countries

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65750

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Elephant Management and Poaching in African Countries

THE NUMBERS DON’T SUPPORT BOTSWANA’S THREAT TO SEND 30,000 ELEPHANTS TO EUROPE

Stephanie Klarmann -- Daily Maverick, 24.04.2024.

Botswana and Zimbabwe have long claimed that their elephant populations are exploding, making hunting a necessity to curtail ‘unsustainable’ growth, but a recent survey contradicts this narrative.

According to the most recent Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (Kaza) survey, elephant populations are stable with a statistically insignificant growth rate of only 1.2% growth per year – an enormous contradiction to Botswana’s claim of 6% annual growth and Zimbabwe’s claims of 5% to 8% annual growth.

However, Elephants Without Borders’ (EWB) recently released a technical review of the Kaza elephant survey reveals that trends in some populations are indeed highly concerning, with poaching and hunting altering elephant distribution and threatening their safety across Africa’s elephant stronghold.

The review notes that while “Kaza’s elephant population appears to be relatively stable overall, the results for Zambia, Botswana and Angola show worrisome indications, including high carcass ratios, large declines, and evidence of recent poaching. These areas should have high priority for future monitoring.”

The technical report contradicts claims of overpopulation by revealing the high carcass ratio found during the elephant surveys across the Kaza region. A carcass ratio of 8% or higher suggests a declining population in which deaths exceed birth rates. The carcass ratio has grown from 8% to 11%, potentially indicating unsustainable mortality rates.

Botswana has threatened to send 10,000 elephants to Hyde Park and now another 20,000 to Germany as UK and European countries continue to debate the import of hunting trophies. According to Botswana’s President Mokgweetsi Masisi, Botswana is heavily overpopulated by elephants, which he believes requires trophy hunting to control.

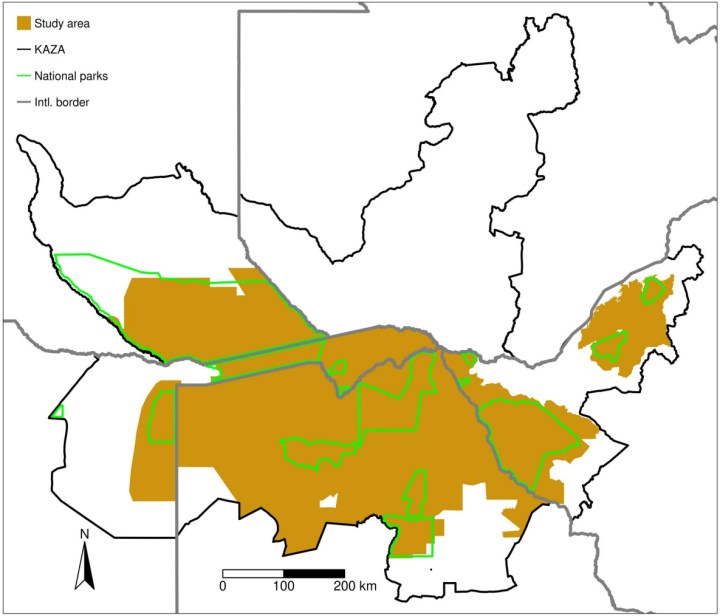

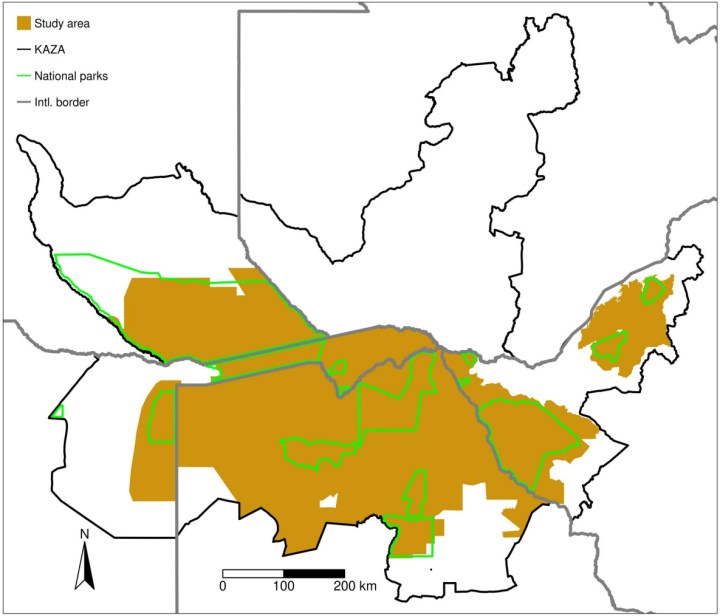

The Elephants Without Borders study area spanning Namibia, Angola, Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe. (Source: Elephants Without Borders)

The Kaza region remains a critical stronghold for Africa’s savannah elephant population, with the latest survey data indicating about 228,000 elephants – just over half of Africa’s savannah elephants.

Botswana

The EWB review notes that elephant numbers in Botswana have increased by 1.3% since the last survey, increasing in national parks and other protected areas, especially in the Okavango, but decreasing in pastoral and agricultural areas, “in contrast to the Botswana government’s claim of 7.6% growth per year”.

Crucially, “numbers of elephants decreased by 25% in areas that were open to hunting and increased by 28% in areas where hunting is not allowed”.

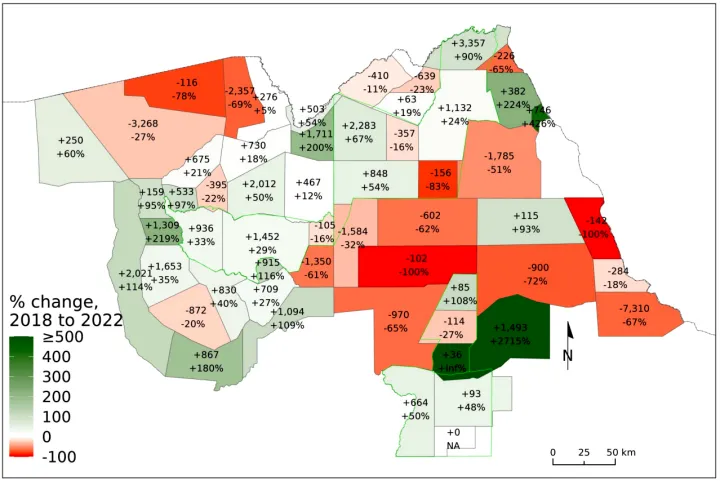

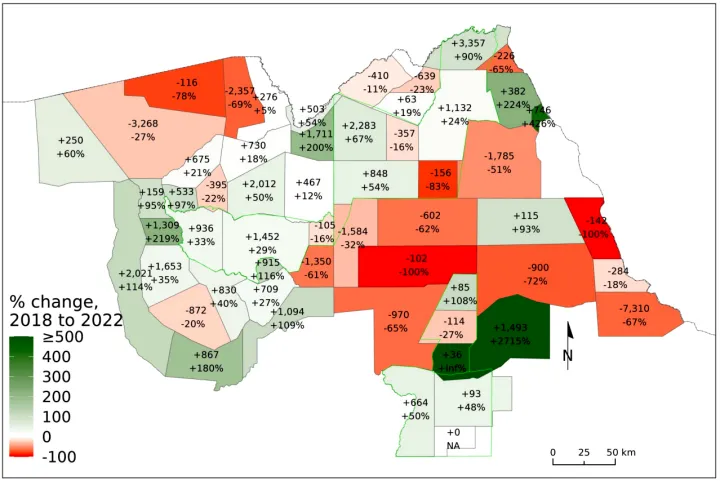

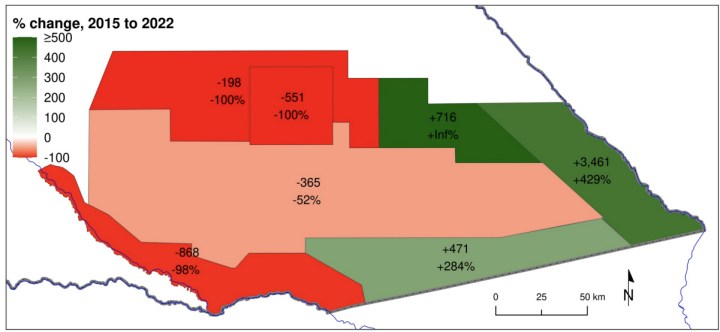

Despite claims regarding a rapidly increasing elephant population, northern Botswana has seen declines of more than 50% in 12 areas between 2018 and 2022. (Source: Elephants Without Borders)

Between October 2023 and February 2024, 56 poached carcasses were located in northern Botswana, which is likely to be an underrepresentation of the true number of poached elephants, highlighting fears that Botswana’s northern regions are becoming a poaching hotspot. According to reports, the poachers are targeting elephants in Botswana before smuggling the tusks into Zambia.

According to Elephants Without Borders, 2022 saw the highest fresh carcass ratio in Botswana, further contradicting claims of a population explosion and no poaching. Just last month, 651 elephant tusks were seized in Maputo, Mozambique, and are likely to have been poached from elephants in neighbouring countries.

The technical review raises concerns that “Kaza contains only seven sites for the Monitoring the Illegal Killing of Elephants (MIKE) programme, which collects data on poaching from ranger patrols. Of the seven sites, four began operation in 2018 or later. This small sample is not sufficient for estimating poaching rates in an area of over 500,000km². More monitoring of poaching is badly needed in Kaza.”

Zimbabwe

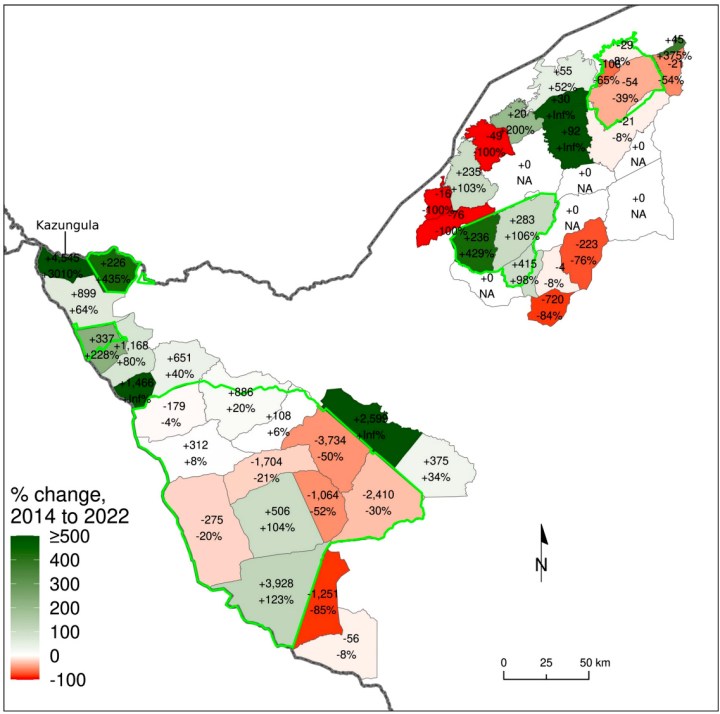

No significant changes were observed in Zimbabwe (see image below) Again, the technical report by Elephants Without Borders contradicts unsubstantiated claims by Zimbabwe at a conference to promote ivory trade that its population is growing unsustainably at 5% to 8% annually. Environmental authorities had previously considered a mass cull of up to 50,000 elephants in 2021, about half of its population.

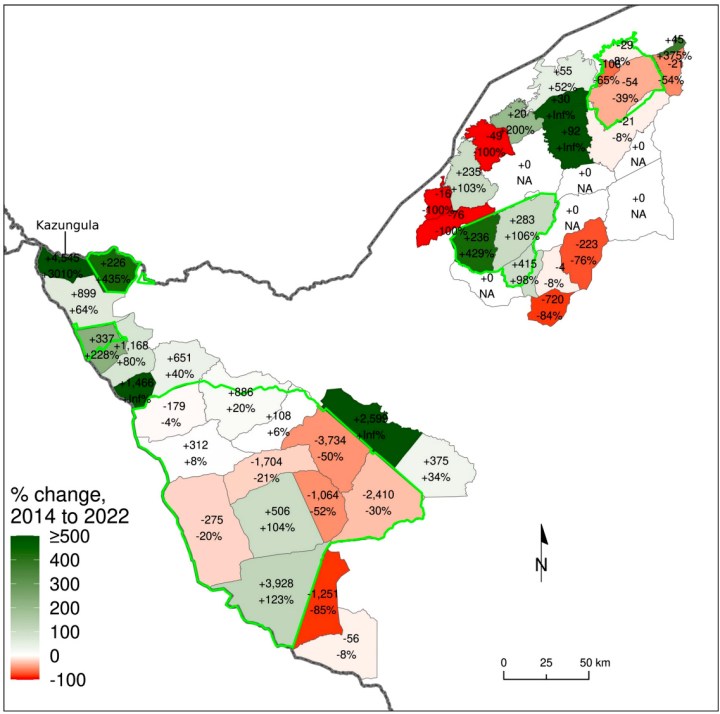

Fourteen areas in Zimbabwe demonstrate decreases in elephant numbers while only six demonstrate significant increases between 2014 and 2022. (Source: Elephants Without Borders)

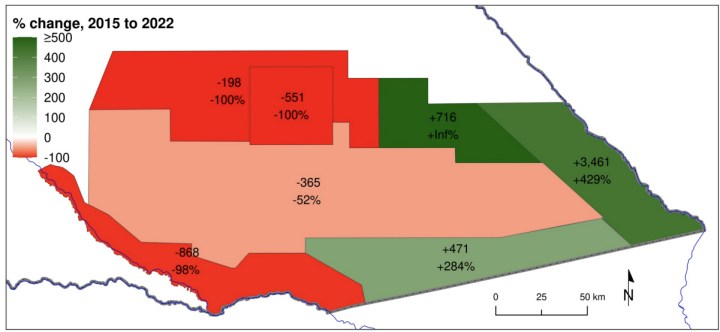

Angola

There is considerable cause for concern regarding Angola’s elephants, as shown in the figure below. The technical report indicates an even higher carcass ratio of 16% in Angola, with 71% of observed carcasses being those of poached elephants. Such a high carcass ratio is concerningly symptomatic of an “attractive population sink” – elephants are “lured to dangerous areas where mortality exceeds natality, contributing to wider population losses”, according to report authors Scott Schlossberg and Mike Chase.

The authors posit that elephants are moving into Angola from the larger populations in Namibia and Botswana but are experiencing high mortality rates in Angola, possibly due to poaching.

This raises questions regarding Botswana’s expressed intention to send 8,000 elephants to Angola in an attempt to reduce its own population. Even if this were physically possible, the elephants are still able to freely move across the region.

Southern Angola demonstrates concerning decreases in elephant populations between 2015 and 2022 in four out of seven regions. (Source: Elephants Without Borders)

Namibia

In Namibia, between 2015 and 2022, the elephant population decreased slightly and non-significantly in the Kavango-Zambezi region and increased non-significantly in Khaudum Nyae-Nyae. Notably, numbers of elephants declined along the Angola and Zambia borders in Kavango-Zambezi. In March 2024, Namibia published a tender for a hunting concession inside the Khaudum National Park.

Botswana trophy hunting debate

Botswana’s government continues to push a strong trophy hunting agenda. In a confusing contradiction, Environment and Tourism Minister Dumezweni Mthimkhulu likened trophy hunting to culling, which was later countered by President Masisi who called culling “ethically abhorrent” and “indiscriminate”.

Botswana reintroduced trophy hunting in 2019 following former president Ian Khama’s ban on sports hunting. Since this reintroduction, survey data indicate that elephant populations are decreasing in ranching, farming and hunting areas and increasing in core conservation areas, most likely as a result of elephant herds moving away from heavily disturbed environments. Trophy hunting cannot be viewed as sustainable if the population is not growing and poaching remains high.

A declaration dated 15 March 2024 has now extended Botswana’s open season on hunting elephants from 2 April 2024 until 31 January 2025. Typically, the hunting season would only last from mid-April to mid-September. The declaration has effectively added five additional months of hunting elephants.

Masisi cites high levels of human-elephant conflict due to burgeoning elephant populations as another reason to promote trophy hunting. However, this argument fails to hold up to scrutiny. Trophy-hunting mature bulls based on trophy-standard characteristics of maximum tusk size does not solve human-elephant conflict, according to the Environmental Investigation Agency’s Mary Rice.

In fact, failure to properly identify and demarcate elephant corridors and allowing hunting in established corridors, such as NG13, risks undermining access routes across transnational boundaries and creating further opportunities for human-elephant conflict to occur. Elephants Without Borders notably states that urgent re-evaluation is required of the effects of trophy hunting in dispersal corridors which are “critical to the Kaza vision of a connected landscape”.

If human-elephant conflict strategies have been implemented with success elsewhere and trophy hunting benefits for communities remain dubious, why push to promote trophy hunting in a country that has been lauded as a wildlife safe haven for so many years? There are claims in the media that this is an election strategy to distract attention from government failures.

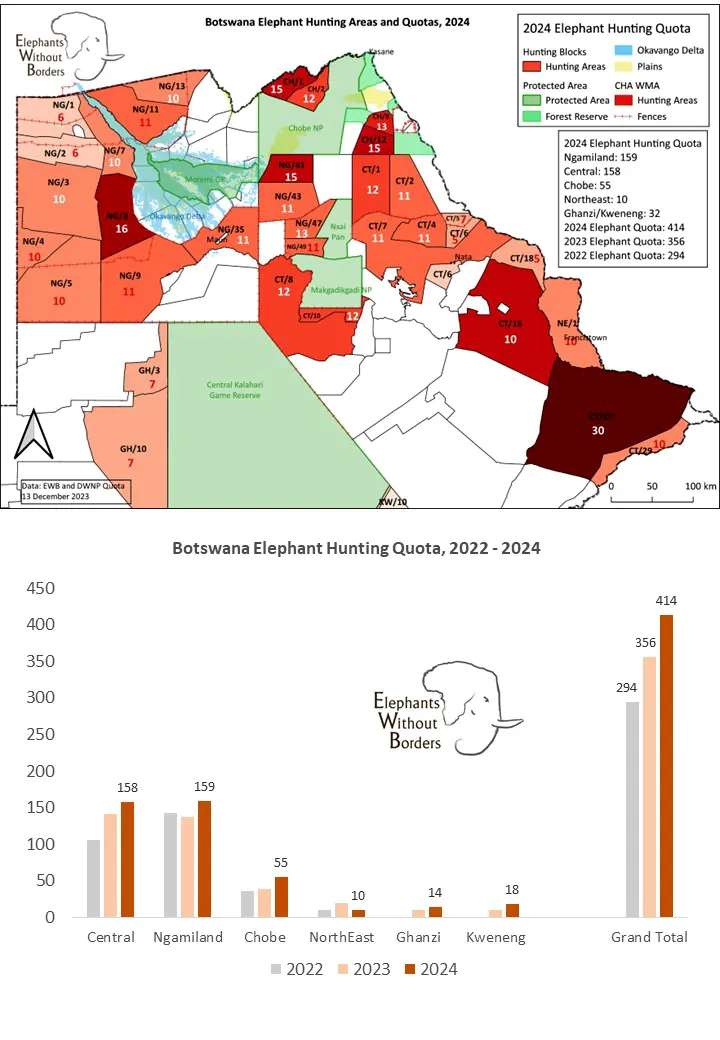

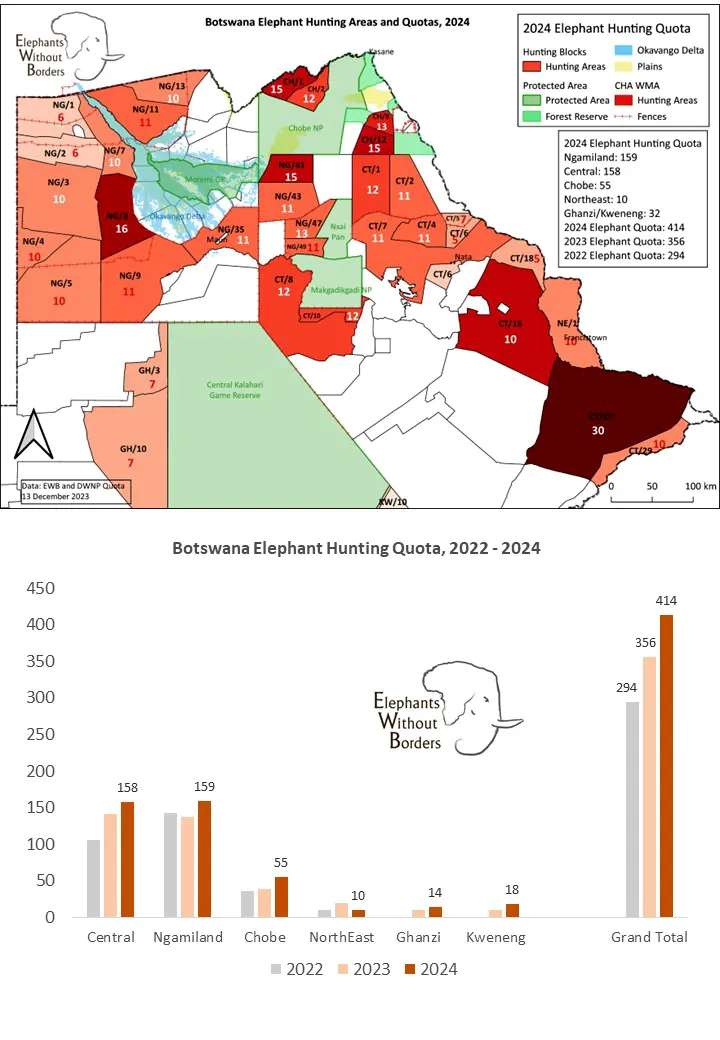

A significant increase in elephant hunting quotas from 2022 to 2024 for Botswana, with up to 30 elephants offered for hunts in a single region in 2024. (Source: Elephants Without Borders)

To fuel concerns, Botswana has yet to publicly share the scientific basis for its trophy hunting quota of 414 elephants for 2024 despite asserting it as a necessary solution.

Several myths regarding elephant populations are taken as scientific fact in certain government and public spheres and require critical scrutiny. One oft-touted myth is carrying capacity, which has again been used to justify ramping up elephant trophy hunting. The notion of carrying capacity was based initially on an outdated policy that lacked scientific backing to manage Hwange’s elephants.

However, researchers largely agree that the distribution of elephants in a landscape has far more relevance than the outdated concept of carrying capacity. The Kaza region offers opportunities for elephants to move across national boundaries, further making carrying capacity in a single country or sub-region irrelevant.

Trophy hunting, in any case, would not solve an overpopulation issue as it only targets the largest and most impressive specimens, effectively depleting the elephant population of its strongest genes. Selectively killing older bulls only serves to decimate genetic diversity. And if bulls beyond breeding age are trophy hunted, then this could never serve to control a supposed “overpopulation” of elephants.

As already demonstrated by the Elephants Without Borders report, trophy hunting and poaching have altered the distribution of elephants across the Kaza countries and even within Botswana’s landscapes, with herds avoiding areas disturbed by a hunting presence.

When science is ignored in favour of rhetoric and misinformation, it is more critical than ever to scrutinise how policy is shaped and who it prioritises. Biodiversity at large is increasingly threatened by overexploitation and unsustainable use. Greenwashing narratives of sustainability and conservation employing misinformation will only serve to harm Kaza’s critical elephant populations.

It is abundantly clear that further research is required to examine the impacts of trophy hunting on elephant populations, especially in light of high poaching statistics, and to better understand ways in which human-elephant conflict can be responsibly mitigated for people and wildlife. DM

Dr Stephanie Klarmann is a conservation psychology researcher based in South Africa. Her work has focused primarily on envisioning a conservation psychology relevant to the South African context with a stronger focus on issues of justice, coexistence and capacity building.

Original source: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinion ... to-europe/

Stephanie Klarmann -- Daily Maverick, 24.04.2024.

Botswana and Zimbabwe have long claimed that their elephant populations are exploding, making hunting a necessity to curtail ‘unsustainable’ growth, but a recent survey contradicts this narrative.

According to the most recent Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (Kaza) survey, elephant populations are stable with a statistically insignificant growth rate of only 1.2% growth per year – an enormous contradiction to Botswana’s claim of 6% annual growth and Zimbabwe’s claims of 5% to 8% annual growth.

However, Elephants Without Borders’ (EWB) recently released a technical review of the Kaza elephant survey reveals that trends in some populations are indeed highly concerning, with poaching and hunting altering elephant distribution and threatening their safety across Africa’s elephant stronghold.

The review notes that while “Kaza’s elephant population appears to be relatively stable overall, the results for Zambia, Botswana and Angola show worrisome indications, including high carcass ratios, large declines, and evidence of recent poaching. These areas should have high priority for future monitoring.”

The technical report contradicts claims of overpopulation by revealing the high carcass ratio found during the elephant surveys across the Kaza region. A carcass ratio of 8% or higher suggests a declining population in which deaths exceed birth rates. The carcass ratio has grown from 8% to 11%, potentially indicating unsustainable mortality rates.

Botswana has threatened to send 10,000 elephants to Hyde Park and now another 20,000 to Germany as UK and European countries continue to debate the import of hunting trophies. According to Botswana’s President Mokgweetsi Masisi, Botswana is heavily overpopulated by elephants, which he believes requires trophy hunting to control.

The Elephants Without Borders study area spanning Namibia, Angola, Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe. (Source: Elephants Without Borders)

The Kaza region remains a critical stronghold for Africa’s savannah elephant population, with the latest survey data indicating about 228,000 elephants – just over half of Africa’s savannah elephants.

Botswana

The EWB review notes that elephant numbers in Botswana have increased by 1.3% since the last survey, increasing in national parks and other protected areas, especially in the Okavango, but decreasing in pastoral and agricultural areas, “in contrast to the Botswana government’s claim of 7.6% growth per year”.

Crucially, “numbers of elephants decreased by 25% in areas that were open to hunting and increased by 28% in areas where hunting is not allowed”.

Despite claims regarding a rapidly increasing elephant population, northern Botswana has seen declines of more than 50% in 12 areas between 2018 and 2022. (Source: Elephants Without Borders)

Between October 2023 and February 2024, 56 poached carcasses were located in northern Botswana, which is likely to be an underrepresentation of the true number of poached elephants, highlighting fears that Botswana’s northern regions are becoming a poaching hotspot. According to reports, the poachers are targeting elephants in Botswana before smuggling the tusks into Zambia.

According to Elephants Without Borders, 2022 saw the highest fresh carcass ratio in Botswana, further contradicting claims of a population explosion and no poaching. Just last month, 651 elephant tusks were seized in Maputo, Mozambique, and are likely to have been poached from elephants in neighbouring countries.

The technical review raises concerns that “Kaza contains only seven sites for the Monitoring the Illegal Killing of Elephants (MIKE) programme, which collects data on poaching from ranger patrols. Of the seven sites, four began operation in 2018 or later. This small sample is not sufficient for estimating poaching rates in an area of over 500,000km². More monitoring of poaching is badly needed in Kaza.”

Zimbabwe

No significant changes were observed in Zimbabwe (see image below) Again, the technical report by Elephants Without Borders contradicts unsubstantiated claims by Zimbabwe at a conference to promote ivory trade that its population is growing unsustainably at 5% to 8% annually. Environmental authorities had previously considered a mass cull of up to 50,000 elephants in 2021, about half of its population.

Fourteen areas in Zimbabwe demonstrate decreases in elephant numbers while only six demonstrate significant increases between 2014 and 2022. (Source: Elephants Without Borders)

Angola

There is considerable cause for concern regarding Angola’s elephants, as shown in the figure below. The technical report indicates an even higher carcass ratio of 16% in Angola, with 71% of observed carcasses being those of poached elephants. Such a high carcass ratio is concerningly symptomatic of an “attractive population sink” – elephants are “lured to dangerous areas where mortality exceeds natality, contributing to wider population losses”, according to report authors Scott Schlossberg and Mike Chase.

The authors posit that elephants are moving into Angola from the larger populations in Namibia and Botswana but are experiencing high mortality rates in Angola, possibly due to poaching.

This raises questions regarding Botswana’s expressed intention to send 8,000 elephants to Angola in an attempt to reduce its own population. Even if this were physically possible, the elephants are still able to freely move across the region.

Southern Angola demonstrates concerning decreases in elephant populations between 2015 and 2022 in four out of seven regions. (Source: Elephants Without Borders)

Namibia

In Namibia, between 2015 and 2022, the elephant population decreased slightly and non-significantly in the Kavango-Zambezi region and increased non-significantly in Khaudum Nyae-Nyae. Notably, numbers of elephants declined along the Angola and Zambia borders in Kavango-Zambezi. In March 2024, Namibia published a tender for a hunting concession inside the Khaudum National Park.

Botswana trophy hunting debate

Botswana’s government continues to push a strong trophy hunting agenda. In a confusing contradiction, Environment and Tourism Minister Dumezweni Mthimkhulu likened trophy hunting to culling, which was later countered by President Masisi who called culling “ethically abhorrent” and “indiscriminate”.

Botswana reintroduced trophy hunting in 2019 following former president Ian Khama’s ban on sports hunting. Since this reintroduction, survey data indicate that elephant populations are decreasing in ranching, farming and hunting areas and increasing in core conservation areas, most likely as a result of elephant herds moving away from heavily disturbed environments. Trophy hunting cannot be viewed as sustainable if the population is not growing and poaching remains high.

A declaration dated 15 March 2024 has now extended Botswana’s open season on hunting elephants from 2 April 2024 until 31 January 2025. Typically, the hunting season would only last from mid-April to mid-September. The declaration has effectively added five additional months of hunting elephants.

Masisi cites high levels of human-elephant conflict due to burgeoning elephant populations as another reason to promote trophy hunting. However, this argument fails to hold up to scrutiny. Trophy-hunting mature bulls based on trophy-standard characteristics of maximum tusk size does not solve human-elephant conflict, according to the Environmental Investigation Agency’s Mary Rice.

In fact, failure to properly identify and demarcate elephant corridors and allowing hunting in established corridors, such as NG13, risks undermining access routes across transnational boundaries and creating further opportunities for human-elephant conflict to occur. Elephants Without Borders notably states that urgent re-evaluation is required of the effects of trophy hunting in dispersal corridors which are “critical to the Kaza vision of a connected landscape”.

If human-elephant conflict strategies have been implemented with success elsewhere and trophy hunting benefits for communities remain dubious, why push to promote trophy hunting in a country that has been lauded as a wildlife safe haven for so many years? There are claims in the media that this is an election strategy to distract attention from government failures.

A significant increase in elephant hunting quotas from 2022 to 2024 for Botswana, with up to 30 elephants offered for hunts in a single region in 2024. (Source: Elephants Without Borders)

To fuel concerns, Botswana has yet to publicly share the scientific basis for its trophy hunting quota of 414 elephants for 2024 despite asserting it as a necessary solution.

Several myths regarding elephant populations are taken as scientific fact in certain government and public spheres and require critical scrutiny. One oft-touted myth is carrying capacity, which has again been used to justify ramping up elephant trophy hunting. The notion of carrying capacity was based initially on an outdated policy that lacked scientific backing to manage Hwange’s elephants.

However, researchers largely agree that the distribution of elephants in a landscape has far more relevance than the outdated concept of carrying capacity. The Kaza region offers opportunities for elephants to move across national boundaries, further making carrying capacity in a single country or sub-region irrelevant.

Trophy hunting, in any case, would not solve an overpopulation issue as it only targets the largest and most impressive specimens, effectively depleting the elephant population of its strongest genes. Selectively killing older bulls only serves to decimate genetic diversity. And if bulls beyond breeding age are trophy hunted, then this could never serve to control a supposed “overpopulation” of elephants.

As already demonstrated by the Elephants Without Borders report, trophy hunting and poaching have altered the distribution of elephants across the Kaza countries and even within Botswana’s landscapes, with herds avoiding areas disturbed by a hunting presence.

When science is ignored in favour of rhetoric and misinformation, it is more critical than ever to scrutinise how policy is shaped and who it prioritises. Biodiversity at large is increasingly threatened by overexploitation and unsustainable use. Greenwashing narratives of sustainability and conservation employing misinformation will only serve to harm Kaza’s critical elephant populations.

It is abundantly clear that further research is required to examine the impacts of trophy hunting on elephant populations, especially in light of high poaching statistics, and to better understand ways in which human-elephant conflict can be responsibly mitigated for people and wildlife. DM

Dr Stephanie Klarmann is a conservation psychology researcher based in South Africa. Her work has focused primarily on envisioning a conservation psychology relevant to the South African context with a stronger focus on issues of justice, coexistence and capacity building.

Original source: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinion ... to-europe/

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75220

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Elephant Management and Poaching in African Countries

Yes they do increase at 6% a year, as has been found in Kruger. The question is now with all the deaths, have they used up all their food? And what does the landscape then look like?

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65750

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Elephant Management and Poaching in African Countries

More grass, fewer trees  They cannot roam the way they used to do and the trees had time to re-grow before they returned to the same place

They cannot roam the way they used to do and the trees had time to re-grow before they returned to the same place

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65750

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Elephant Management and Poaching in African Countries

Elephant poaching in Africa is on the decline — but there’s no room for complacency

Elephants with a juvenile at the Kruger National Park, Limpopo. (Photo: Sarel van der Walt / Gallo Images)

By Adam Cruise | 02 Jun 2024

The wave of elephant poaching over the past two decades appears to have substantially subsided while prices of ivory have collapsed, but there remain serious threats to some elephant populations.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

According to the 2024 report from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the international ivory market is shrinking, prices are collapsing while ivory seizures and elephant poaching figures are decreasing. This appears to be the result of a multitude of supply and demand interventions.

The closure of a number of key domestic markets, such as those in China, the US, Europe and Thailand have constrained demand while on the supply side, a series of convictions of high-level traffickers who operated in Africa and Asia “may have facilitated a constrained flow of illicit ivory, as captured in the decline in aggregated seizure volumes”.

Importantly, these factors have not resulted in an increase in ivory prices. According to the report, the collapse in prices means that demand for ivory has “truly declined”.

This runs contrary to the long-held belief of southern African governments that ivory price reduction will only occur after a legalisation of international ivory trade when legal supply would outstrip demand and reduce prices, making poaching uneconomical.

From 2007 to 2014, Africa lost around one-third of its savannah elephant populations, while forest elephant populations dropped by 86%. Seizure data analysed in the UNODC World Wildlife Crime Report in 2016 showed that most of the extensive illegal flow of elephant ivory was headed for Asian markets.

Bursting the bubble

However, in the mid-2010s, trends in indicators of poaching, trafficking, and the retail market all suggested that the supply of ivory had begun exceeding demand and that this trend has, in recent years, accelerated as national ivory controls in the US and China came into effect. Based on several independent data sources analysed by UNODC, the destination market wholesale prices in 2018 were one-third what they had been in 2014.

By 2020, prices appeared to be dropping to new lows in both Africa and most of Asia. In Africa, between 2014 and 2018 the price per kilogram of raw ivory was around $400. By 2023, those prices had dropped to under $200/kg.

Other research shows that the prices paid for raw ivory in Africa in 2020 were as low as $92/kg on the black market. On the demand side in Asia, prices dropped from more than $1,000/kg of raw ivory in 2015 to an average $400/kg in 2021 on the retail market.

This makes a mockery of Zimbabwe’s claim that its ivory stockpile of 130 tonnes is worth $600-million, which gives an unrealistic figure of more than $4,600/kg. Therefore, a more realistic valuation of Zimbabwe’s ivory stockpiles, using an optimistic wholesale price of $150/kg, would give a potential income of only $19.5-million. This is a 30th of Zimbabwe’s estimate.

Zimbabwe, along with Botswana, Namibia and South Africa, are pushing to sell their stockpiles on the international market.

This further undermines South Africa’s intention, as laid out in the recent National Biodiversity Economy Strategy (NBES), to “stimulate the domestic market in elephant ivory” for Asian tourists. This is a dangerous ploy in view of this report’s revelations that the closure of domestic ivory markets has reduced elephant poaching. It follows that any stimulation of demand would naturally increase poaching.

The latest information suggests that these trends are continuing. The number of detected poached elephants continues to decline overall, with 2021 being one of the lowest totals on record. Apart from a spike in 2019, the number of ivory seizures has reduced too.

According to the most recent Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (Kaza) survey, elephant populations are stable but with a statistically insignificant growth rate of only 1.2% per year coupled with high carcass ratios. Kaza, which spans five southern African countries – Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe – is home to almost 230,000 elephants, the largest stronghold of savannah elephants on Earth.

Botswana-based organisation Elephants Without Borders (EWB) released a technical review of the Kaza elephant survey. The review flags the high levels of poaching indicated by high carcass ratios across northern Botswana. A carcass ratio of 8% or higher means the population will begin to decline as deaths exceed birth rates. The fact that carcass ratios have increased from 8% to 12% for Botswana means it’s one dead elephant for every 10 live ones counted. This statistic of one dead for every 10 live elephants remains roughly the same across the whole Kaza region.

Since October 2023, a total of 85 elephants have been poached in Botswana. There are clear indications that gangs from Zambia and Namibia are operating in these areas with impunity.

Furthermore, analyses of large ivory seizures from 2016 to 2019 suggest that the largest elephant poaching hotspot in Africa may have shifted south, from east Africa to northern Botswana and neighbouring countries. Zambia’s elephant population remains in a steep decline. Against the overall trend, the country lost more than a third of its population between 2016 and 2022, having previously recorded an 85% carcass ratio (eight dead for every one live elephant) in Sioma Ngwezi in southwestern Zambia, which borders Namibia and Angola.

Elsewhere, West and Central Africa are still recording high levels of elephant poaching. Forest elephants continue to show a sharp decline in their two strongholds in Gabon and Republic of Congo. The species’ Red Data listing changed from Vulnerable to Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2019. The savannah elephant is now listed as Endangered.

And while overall number of ivory seizures are declining, the report highlights that in 2019, three of the largest-ever ivory seizures were made, totalling 25 tonnes – 7.5 tonnes in China en route from Nigeria; 8.8 tonnes in Singapore from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC); and 9.1 tonnes in Vietnam also from the DRC.

The report also cautioned that periodic seizures of several tonnes of ivory in 2021 and 2022 indicates that organised criminal activity is still evident. Seizures in 2021 were made in Nigeria (4.7 tonnes), South Africa (7.5 tonnes) and the DRC (7 tonnes). There were two large seizures linked to Mozambique in 2022, one made in that country (7 tonnes) and the other later along the trade chain in Malaysia (4.2 tonnes).

Other large seizures were in the DRC in 2022 (1.5 tonnes), a seizure in Vietnam of a shipment from Angola in 2023 (7 tonnes) and most recently in March 2024, a seizure of 4.8 tonnes of ivory in Mozambique reportedly en route to the United Arab Emirates.

Guarded optimism

The decline of ivory prices in the face of declining supply suggests that it is a genuine decline in demand that, in turn, has led to an overall decline in elephant poaching in Africa. However, the continued threat to some elephant populations is a worry, as is the continued insistence of southern African countries to try to sell off their ivory stockpiles.

The report concludes that “persistent detection of large shipments of ivory highlights the continued existence of both a market and those willing to invest in it. While progress has been made on many fronts, the threat to local elephant populations has not gone away.”

In analysing the report, Tanya Sanerib, the international legal director at the Centre for Biological Diversity agrees. “The clear takeaway from this report is that we need to stay vigilant on elephants,” she said. “Closing domestic ivory markets and reducing demand have undeniably helped, but one look at northern Botswana shows the elephant-poaching epidemic is far from over. We have to keep up our efforts to combat poaching and ivory trafficking.” DM

Elephants with a juvenile at the Kruger National Park, Limpopo. (Photo: Sarel van der Walt / Gallo Images)

By Adam Cruise | 02 Jun 2024

The wave of elephant poaching over the past two decades appears to have substantially subsided while prices of ivory have collapsed, but there remain serious threats to some elephant populations.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

According to the 2024 report from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the international ivory market is shrinking, prices are collapsing while ivory seizures and elephant poaching figures are decreasing. This appears to be the result of a multitude of supply and demand interventions.

The closure of a number of key domestic markets, such as those in China, the US, Europe and Thailand have constrained demand while on the supply side, a series of convictions of high-level traffickers who operated in Africa and Asia “may have facilitated a constrained flow of illicit ivory, as captured in the decline in aggregated seizure volumes”.

Importantly, these factors have not resulted in an increase in ivory prices. According to the report, the collapse in prices means that demand for ivory has “truly declined”.

This runs contrary to the long-held belief of southern African governments that ivory price reduction will only occur after a legalisation of international ivory trade when legal supply would outstrip demand and reduce prices, making poaching uneconomical.

From 2007 to 2014, Africa lost around one-third of its savannah elephant populations, while forest elephant populations dropped by 86%. Seizure data analysed in the UNODC World Wildlife Crime Report in 2016 showed that most of the extensive illegal flow of elephant ivory was headed for Asian markets.

Bursting the bubble

However, in the mid-2010s, trends in indicators of poaching, trafficking, and the retail market all suggested that the supply of ivory had begun exceeding demand and that this trend has, in recent years, accelerated as national ivory controls in the US and China came into effect. Based on several independent data sources analysed by UNODC, the destination market wholesale prices in 2018 were one-third what they had been in 2014.

By 2020, prices appeared to be dropping to new lows in both Africa and most of Asia. In Africa, between 2014 and 2018 the price per kilogram of raw ivory was around $400. By 2023, those prices had dropped to under $200/kg.

Other research shows that the prices paid for raw ivory in Africa in 2020 were as low as $92/kg on the black market. On the demand side in Asia, prices dropped from more than $1,000/kg of raw ivory in 2015 to an average $400/kg in 2021 on the retail market.

This makes a mockery of Zimbabwe’s claim that its ivory stockpile of 130 tonnes is worth $600-million, which gives an unrealistic figure of more than $4,600/kg. Therefore, a more realistic valuation of Zimbabwe’s ivory stockpiles, using an optimistic wholesale price of $150/kg, would give a potential income of only $19.5-million. This is a 30th of Zimbabwe’s estimate.

Zimbabwe, along with Botswana, Namibia and South Africa, are pushing to sell their stockpiles on the international market.

This further undermines South Africa’s intention, as laid out in the recent National Biodiversity Economy Strategy (NBES), to “stimulate the domestic market in elephant ivory” for Asian tourists. This is a dangerous ploy in view of this report’s revelations that the closure of domestic ivory markets has reduced elephant poaching. It follows that any stimulation of demand would naturally increase poaching.

The latest information suggests that these trends are continuing. The number of detected poached elephants continues to decline overall, with 2021 being one of the lowest totals on record. Apart from a spike in 2019, the number of ivory seizures has reduced too.

According to the most recent Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (Kaza) survey, elephant populations are stable but with a statistically insignificant growth rate of only 1.2% per year coupled with high carcass ratios. Kaza, which spans five southern African countries – Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe – is home to almost 230,000 elephants, the largest stronghold of savannah elephants on Earth.

Botswana-based organisation Elephants Without Borders (EWB) released a technical review of the Kaza elephant survey. The review flags the high levels of poaching indicated by high carcass ratios across northern Botswana. A carcass ratio of 8% or higher means the population will begin to decline as deaths exceed birth rates. The fact that carcass ratios have increased from 8% to 12% for Botswana means it’s one dead elephant for every 10 live ones counted. This statistic of one dead for every 10 live elephants remains roughly the same across the whole Kaza region.

Since October 2023, a total of 85 elephants have been poached in Botswana. There are clear indications that gangs from Zambia and Namibia are operating in these areas with impunity.

Furthermore, analyses of large ivory seizures from 2016 to 2019 suggest that the largest elephant poaching hotspot in Africa may have shifted south, from east Africa to northern Botswana and neighbouring countries. Zambia’s elephant population remains in a steep decline. Against the overall trend, the country lost more than a third of its population between 2016 and 2022, having previously recorded an 85% carcass ratio (eight dead for every one live elephant) in Sioma Ngwezi in southwestern Zambia, which borders Namibia and Angola.

Elsewhere, West and Central Africa are still recording high levels of elephant poaching. Forest elephants continue to show a sharp decline in their two strongholds in Gabon and Republic of Congo. The species’ Red Data listing changed from Vulnerable to Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2019. The savannah elephant is now listed as Endangered.

And while overall number of ivory seizures are declining, the report highlights that in 2019, three of the largest-ever ivory seizures were made, totalling 25 tonnes – 7.5 tonnes in China en route from Nigeria; 8.8 tonnes in Singapore from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC); and 9.1 tonnes in Vietnam also from the DRC.

The report also cautioned that periodic seizures of several tonnes of ivory in 2021 and 2022 indicates that organised criminal activity is still evident. Seizures in 2021 were made in Nigeria (4.7 tonnes), South Africa (7.5 tonnes) and the DRC (7 tonnes). There were two large seizures linked to Mozambique in 2022, one made in that country (7 tonnes) and the other later along the trade chain in Malaysia (4.2 tonnes).

Other large seizures were in the DRC in 2022 (1.5 tonnes), a seizure in Vietnam of a shipment from Angola in 2023 (7 tonnes) and most recently in March 2024, a seizure of 4.8 tonnes of ivory in Mozambique reportedly en route to the United Arab Emirates.

Guarded optimism

The decline of ivory prices in the face of declining supply suggests that it is a genuine decline in demand that, in turn, has led to an overall decline in elephant poaching in Africa. However, the continued threat to some elephant populations is a worry, as is the continued insistence of southern African countries to try to sell off their ivory stockpiles.

The report concludes that “persistent detection of large shipments of ivory highlights the continued existence of both a market and those willing to invest in it. While progress has been made on many fronts, the threat to local elephant populations has not gone away.”

In analysing the report, Tanya Sanerib, the international legal director at the Centre for Biological Diversity agrees. “The clear takeaway from this report is that we need to stay vigilant on elephants,” she said. “Closing domestic ivory markets and reducing demand have undeniably helped, but one look at northern Botswana shows the elephant-poaching epidemic is far from over. We have to keep up our efforts to combat poaching and ivory trafficking.” DM

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65750

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Elephant Management and Poaching in African Countries

Nigeria’s last elephants – what must be done to save them

Published: October 30, 2024 - judeen Amusa - Professor, Forest Resources Management, University of Ilorin

Nigeria has a unique elephant population, made up of both forest-dwelling (Loxodonta cyclotis) and savanna-dwelling (Loxodonta africana) elephant species. But the animals are facing unprecedented threats to their survival. In about 30 years, Nigeria’s elephant population has crashed from an estimated 1,200-1,500 to an estimated 300-400 today. About 200-300 are forest elephants and 100 savanna elephants.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) recently classified the forest elephant as “critically endangered” and the savanna elephant as “endangered”.

The country has never had herds in the multiple thousands, but its elephants have played a vital ecological role, balancing natural ecosystems.

Today they live primarily in protected areas and in small forest fragments where they are increasingly isolated and vulnerable to extinction. They are found in Chad Basin National Park in Borno State and Yankari Game Reserve in Bauchi State. Also in Omo Forests Reserve in Ogun State, Okomu National Park in Edo State and Cross River National Park in Cross River State.

Elephants in Nigeria are threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation, poaching and illegal ivory trade, human-elephant conflict and climate change. These issues are pushing them to the brink of extinction.

In August 2024 Nigeria launched the country’s first National Elephant Action Plan. The 10-year strategic plan aims to ensure the long-term survival of elephants in Nigeria.

But will it?

As a conservationist with research in elephant conservation, I think this plan is a promising initiative. It could ensure the survival of Nigeria’s elephants. However, the long-term sustainability of the elephant populations in Nigeria depends on how well the plan balances conservation efforts with economic development. The government must also be willing to support the plan. It must commit financial resources to carry out the plan.

Here I set out the threats to elephants in Nigeria and four urgent steps needed to save these animals. Taking these steps will help make the strategic plan a reality.

Threats to elephants in Nigeria

Expansion of agriculture, urbanisation and infrastructure development leads to habitat loss and fragmentation. The destruction of elephant habitats means that populations are isolated. This has made it difficult for the animal to migrate, find food and breed. At about 3.5% a year, the rate of forest loss in Nigeria is among the highest globally.

Poaching of elephants for their ivory and traditional medicinal value is another menace. Despite the ivory trade ban under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, Nigeria-linked ivory seizures amounted to 12,211kg in the period 2015-2017. In January 2024, Nigeria destroyed 2.5 tonnes of seized elephant tusks valued at over 9.9 billion naira (US$11.2 million).

Human-elephant conflict is a growing challenge. As elephants lose their habitats, they encroach on farmland, leading to conflicts with people. Elephants damage crops. In retaliation, some communities harm or kill the elephants.

Climate change is another threat to the survival of elephants in the country. Water scarcity and food insecurity affect both humans and elephants. Elephants are forced to venture into human-dominated landscapes, increasing conflicts.

Read more: Nigeria risks losing all its forest elephants – what we found when we went looking for them

Saving endangered elephants in Nigeria

To save its elephants, Nigeria needs to take the following steps.

Strengthen existing protected areas: It is important to restore and safeguard elephants’ habitats. Existing national parks, forest and game reserves should be strengthened to prevent further destruction and fragmentation. Wildlife corridors to reconnect fragmented populations are also crucial. This should be based on management plans approved by government agencies, conservationists and local communities.

Combat poaching and ivory trafficking: Wildlife laws must be enforced to disrupt the ivory trade networks. The capacity of park rangers, wildlife law enforcers and local authorities to combat poaching must be enhanced. Advanced surveillance tools such as drones and camera traps must be provided. There should also be regular training for law enforcement officers to keep up with modern anti-poaching tactics.

Stricter penalties for wildlife crimes and effective prosecution of offenders will deter poachers too.

Promote human-elephant coexistence: This requires innovative and community-driven solutions.

One approach is the use of early warning systems and deterrent measures, such as beehive fences. They have been effective in deterring elephants from entering farmlands. Training and equipping local communities to monitor elephant movements can also help avoid conflicts. Compensation schemes for farmers who suffer losses from elephant raids can foster positive attitudes towards conservation.

Expanding public awareness and conservation education: Some Nigerians may not fully understand the ecological and cultural importance of elephants. Awareness of their role in maintaining ecosystem health and the consequences of their extinction is key to fostering support for protection.

Schools, community groups and media should be engaged in conservation education initiatives. This will promote a sense of ownership and responsibility for preserving Nigeria’s wildlife generally.

Why Nigeria must save its elephants

Saving elephants is not only a matter of preserving biodiversity but also ensuring the health of entire ecosystems.

Elephants are keystone species; they create and maintain habitats that support other species. They shape the landscape, disperse seeds, and create water holes that benefit a wide variety of wildlife. Losing them would have cascading effects on the environment.

Economically, elephants are valuable for ecotourism. They can provide sustainable income to local communities. Protecting elephants could be an alternative to poaching or illegal logging.

Culturally, elephants hold symbolic and spiritual value for many Nigerians. Their presence is linked to heritage and identity of communities.

Protecting elephants in Nigeria is not only about conserving a species. It is about preserving the country’s ecological integrity, supporting sustainable livelihoods, and safeguarding the natural heritage for future generations. The time to act is now.

Published: October 30, 2024 - judeen Amusa - Professor, Forest Resources Management, University of Ilorin

Nigeria has a unique elephant population, made up of both forest-dwelling (Loxodonta cyclotis) and savanna-dwelling (Loxodonta africana) elephant species. But the animals are facing unprecedented threats to their survival. In about 30 years, Nigeria’s elephant population has crashed from an estimated 1,200-1,500 to an estimated 300-400 today. About 200-300 are forest elephants and 100 savanna elephants.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) recently classified the forest elephant as “critically endangered” and the savanna elephant as “endangered”.

The country has never had herds in the multiple thousands, but its elephants have played a vital ecological role, balancing natural ecosystems.

Today they live primarily in protected areas and in small forest fragments where they are increasingly isolated and vulnerable to extinction. They are found in Chad Basin National Park in Borno State and Yankari Game Reserve in Bauchi State. Also in Omo Forests Reserve in Ogun State, Okomu National Park in Edo State and Cross River National Park in Cross River State.

Elephants in Nigeria are threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation, poaching and illegal ivory trade, human-elephant conflict and climate change. These issues are pushing them to the brink of extinction.

In August 2024 Nigeria launched the country’s first National Elephant Action Plan. The 10-year strategic plan aims to ensure the long-term survival of elephants in Nigeria.

But will it?

As a conservationist with research in elephant conservation, I think this plan is a promising initiative. It could ensure the survival of Nigeria’s elephants. However, the long-term sustainability of the elephant populations in Nigeria depends on how well the plan balances conservation efforts with economic development. The government must also be willing to support the plan. It must commit financial resources to carry out the plan.

Here I set out the threats to elephants in Nigeria and four urgent steps needed to save these animals. Taking these steps will help make the strategic plan a reality.

Threats to elephants in Nigeria

Expansion of agriculture, urbanisation and infrastructure development leads to habitat loss and fragmentation. The destruction of elephant habitats means that populations are isolated. This has made it difficult for the animal to migrate, find food and breed. At about 3.5% a year, the rate of forest loss in Nigeria is among the highest globally.

Poaching of elephants for their ivory and traditional medicinal value is another menace. Despite the ivory trade ban under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, Nigeria-linked ivory seizures amounted to 12,211kg in the period 2015-2017. In January 2024, Nigeria destroyed 2.5 tonnes of seized elephant tusks valued at over 9.9 billion naira (US$11.2 million).

Human-elephant conflict is a growing challenge. As elephants lose their habitats, they encroach on farmland, leading to conflicts with people. Elephants damage crops. In retaliation, some communities harm or kill the elephants.

Climate change is another threat to the survival of elephants in the country. Water scarcity and food insecurity affect both humans and elephants. Elephants are forced to venture into human-dominated landscapes, increasing conflicts.

Read more: Nigeria risks losing all its forest elephants – what we found when we went looking for them

Saving endangered elephants in Nigeria

To save its elephants, Nigeria needs to take the following steps.

Strengthen existing protected areas: It is important to restore and safeguard elephants’ habitats. Existing national parks, forest and game reserves should be strengthened to prevent further destruction and fragmentation. Wildlife corridors to reconnect fragmented populations are also crucial. This should be based on management plans approved by government agencies, conservationists and local communities.

Combat poaching and ivory trafficking: Wildlife laws must be enforced to disrupt the ivory trade networks. The capacity of park rangers, wildlife law enforcers and local authorities to combat poaching must be enhanced. Advanced surveillance tools such as drones and camera traps must be provided. There should also be regular training for law enforcement officers to keep up with modern anti-poaching tactics.

Stricter penalties for wildlife crimes and effective prosecution of offenders will deter poachers too.

Promote human-elephant coexistence: This requires innovative and community-driven solutions.

One approach is the use of early warning systems and deterrent measures, such as beehive fences. They have been effective in deterring elephants from entering farmlands. Training and equipping local communities to monitor elephant movements can also help avoid conflicts. Compensation schemes for farmers who suffer losses from elephant raids can foster positive attitudes towards conservation.

Expanding public awareness and conservation education: Some Nigerians may not fully understand the ecological and cultural importance of elephants. Awareness of their role in maintaining ecosystem health and the consequences of their extinction is key to fostering support for protection.

Schools, community groups and media should be engaged in conservation education initiatives. This will promote a sense of ownership and responsibility for preserving Nigeria’s wildlife generally.

Why Nigeria must save its elephants

Saving elephants is not only a matter of preserving biodiversity but also ensuring the health of entire ecosystems.

Elephants are keystone species; they create and maintain habitats that support other species. They shape the landscape, disperse seeds, and create water holes that benefit a wide variety of wildlife. Losing them would have cascading effects on the environment.

Economically, elephants are valuable for ecotourism. They can provide sustainable income to local communities. Protecting elephants could be an alternative to poaching or illegal logging.

Culturally, elephants hold symbolic and spiritual value for many Nigerians. Their presence is linked to heritage and identity of communities.

Protecting elephants in Nigeria is not only about conserving a species. It is about preserving the country’s ecological integrity, supporting sustainable livelihoods, and safeguarding the natural heritage for future generations. The time to act is now.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65750

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Elephant Management and Poaching in African Countries

BUSINESS REFLECTION

Southern Africa’s secret to elephant conservation success — it’s the economy, stupid

Rescue elephants are led to a reserve waterhole for bathing and drinking at a an orphanage outside Hoedspruit, Limpopo. (Photo: Tiara Walters)

By Ed Stoddard |14 Nov 2024

Southern Africa is bucking the trend on the continent in terms of the decline in elephant populations, according to studies. And the reasons have a lot to do with economics.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A study published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy Sciences has confirmed two widely known facts regarding African elephants but provided fresh data to flesh out the big picture.

The peer-reviewed paper – Survey-based inference of continental African elephant decline – examined hundreds of population surveys of forest and savanna elephants from 475 sites across 37 African countries between 1964 and 2016.

“Both species have experienced substantial declines at the majority of survey sites. Forest elephant sites have declined on average by 90%, whereas savanna elephant sites have declined by 70% over the study period,” the study says.

But the study notes that there are mammoth-sized regional variations, with southern Africa notably bucking the trend.

“For the south, 42% of sites demonstrated a density increase over the modelled period. In contrast, only 10% of east sites are estimated to have increased, and none in the north,” it says.

Both trends are well known in conservation circles – in much of southern Africa, populations have been rising but, overall, in Africa, elephants are in precipitous decline for a range of reasons, including ivory poaching, habitat destruction, and fragmentation and conflict with humans.

This is the most exhaustive number-crunching on population surveys to date, providing plenty of food for thought for policymakers and conservationists.

“… a comprehensive evaluation of trend information from African elephant populations over the past half-century has been a critical outstanding scientific need necessary for informing debate around the species management and conservation. The results presented here fulfil this need,” the study says.

“These results indicated that conservation efforts are succeeding in some sites across regions of Africa. Such heterogeneity offers opportunities to identify key factors related to the efficacy of conservation efforts.”

The paper does not make policy recommendations, and most of the headlines about the study have been about the alarming decline in Africa’s elephant populations.

But the study does offer clues to what works and what doesn’t work for elephant conservation. And economics clearly plays a role.

Factors that have contributed to elephant conservation

One economic factor is costs. South Africa, for example, is the one significant elephant range state where the pachyderms are almost exclusively contained in fenced reserves. And those that are not, are meant to be fenced.

South Africa is also by far the most industrialised African economy, with the continent’s most capital-intensive commercial agricultural sector.

Fencing is the costly response of a relatively affluent and industrialised economy to potentially menacing megafauna and is a policy option that the ANC inherited in 1994 and has pointedly maintained.

Containment also minimises human-wildlife conflict, which is good for animals and people. But fences have mixed results as a deterrence to poaching, a point underscored by the rhino carnage in Kruger National Park.

One of the drawbacks to fencing is the potential ecological consequences of elephant populations swelling to a point where they eat themselves out of house and home – they need room to roam.

Another economic point to make is that South Africa allows private ownership of game. On the megafauna front, most of the country’s white rhino population is in private hands, largely because the owners have done a far better job protecting their herds than has been the case in state-run reserves. They have assets and that drives incentives to protect their property.

There are also elephants on private land in South Africa. But one of the ramifications of this conservation success story is that fewer private game ranchers want elephants because there are so many of the pachyderms in South Africa these days. So, South Africa’s elephant population could potentially be approaching a peak.

Ecotourism also plays a big role in the economics equation, both “non-consumptive” and “consumptive” – the former focuses on photographic wildlife excursions or simply watching animals, while the latter includes activities such as hunting.

With a couple of notable exceptions such as Kenya, southern Africa has by far the most developed “non-consumptive” ecotourism sector on the continent.

Botswana has Africa’s biggest population of elephants, with around 130,000. This state of affairs is partly explained by the fact that Botswana is sparsely populated by humans, who number around 2.5 million, and the pachyderms are mostly in remote areas with few people.

But Botswana also has a thriving non-consumptive ecotourism – or “safari” – sector that creates economic incentives to protect and maintain wildlife, including elephants. Tourism accounts, it seems, for about 13% of Botswana’s GDP.

Namibia, Zambia, South Africa and, to a lesser extent, Zimbabwe also have robust non-consumptive ecotourist offerings that bring in foreign currency, create jobs and business opportunities, and help ensure that prime elephant habitat is not turned into farmland or a mine or some such thing.

On the other hand

The flip side of the ecotourist sector is the elephant in the room – trophy hunting.

This makes animal welfare and rights activists, especially up north – you know, the countries that don’t have much in the way of dangerous megafauna – see red.

Opposition to hunting is perfectly legitimate; a lot of people simply do not like it for whatever reason.

But the problem is that it is often woefully misinformed and, in the case of Africa especially, fails to take into account the views of people who actually have to live in proximity to big animals that could kill their kith and kin or devour their crops.

One cold hard fact of this matter is that outside of Cameroon in the west and Tanzania in the east, southern Africa is the one region on the continent that also has several elephant range states, where the animals can be legally hunted for sport: South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Mozambique.

And this is the region that has gone against the grain of elephant decline in Africa. To use a term from the dismal science, this is called an “economic indicator” and, in this case, it is one that can also be seen as an “ecological indicator”.

There is a lot of wrangling about how much money from hunting trickles down to the rural poor, but the same can be said about photographic tourism. And many areas where hunting takes place are unsuitable for photographic tourism because of the terrain, remoteness and lack of amenities.

As the authors of the study note, their research is aimed at informing debate on these issues.

On that score, a recent Oxford-led study found that campaigns such as those in the UK to ban the import of hunting trophies – and Africa is the main target – were counterproductive “[…] as hunting does, or could potentially, benefit 20 species and subspecies, and people”.

“Legal hunting for trophies is not a major threat to any of the species or subspecies imported to the UK, but likely or possibly represents a local threat to some populations of eight species,” the study found.

When it comes to elephant conservation, the phrase coined by James Carville, a strategist in Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 US presidential campaign, comes to mind. “It’s the economy, stupid.” DM

Southern Africa’s secret to elephant conservation success — it’s the economy, stupid

Rescue elephants are led to a reserve waterhole for bathing and drinking at a an orphanage outside Hoedspruit, Limpopo. (Photo: Tiara Walters)

By Ed Stoddard |14 Nov 2024

Southern Africa is bucking the trend on the continent in terms of the decline in elephant populations, according to studies. And the reasons have a lot to do with economics.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A study published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy Sciences has confirmed two widely known facts regarding African elephants but provided fresh data to flesh out the big picture.

The peer-reviewed paper – Survey-based inference of continental African elephant decline – examined hundreds of population surveys of forest and savanna elephants from 475 sites across 37 African countries between 1964 and 2016.

“Both species have experienced substantial declines at the majority of survey sites. Forest elephant sites have declined on average by 90%, whereas savanna elephant sites have declined by 70% over the study period,” the study says.

But the study notes that there are mammoth-sized regional variations, with southern Africa notably bucking the trend.

“For the south, 42% of sites demonstrated a density increase over the modelled period. In contrast, only 10% of east sites are estimated to have increased, and none in the north,” it says.

Both trends are well known in conservation circles – in much of southern Africa, populations have been rising but, overall, in Africa, elephants are in precipitous decline for a range of reasons, including ivory poaching, habitat destruction, and fragmentation and conflict with humans.

This is the most exhaustive number-crunching on population surveys to date, providing plenty of food for thought for policymakers and conservationists.

“… a comprehensive evaluation of trend information from African elephant populations over the past half-century has been a critical outstanding scientific need necessary for informing debate around the species management and conservation. The results presented here fulfil this need,” the study says.

“These results indicated that conservation efforts are succeeding in some sites across regions of Africa. Such heterogeneity offers opportunities to identify key factors related to the efficacy of conservation efforts.”

The paper does not make policy recommendations, and most of the headlines about the study have been about the alarming decline in Africa’s elephant populations.

But the study does offer clues to what works and what doesn’t work for elephant conservation. And economics clearly plays a role.

Factors that have contributed to elephant conservation

One economic factor is costs. South Africa, for example, is the one significant elephant range state where the pachyderms are almost exclusively contained in fenced reserves. And those that are not, are meant to be fenced.

South Africa is also by far the most industrialised African economy, with the continent’s most capital-intensive commercial agricultural sector.

Fencing is the costly response of a relatively affluent and industrialised economy to potentially menacing megafauna and is a policy option that the ANC inherited in 1994 and has pointedly maintained.

Containment also minimises human-wildlife conflict, which is good for animals and people. But fences have mixed results as a deterrence to poaching, a point underscored by the rhino carnage in Kruger National Park.

One of the drawbacks to fencing is the potential ecological consequences of elephant populations swelling to a point where they eat themselves out of house and home – they need room to roam.

Another economic point to make is that South Africa allows private ownership of game. On the megafauna front, most of the country’s white rhino population is in private hands, largely because the owners have done a far better job protecting their herds than has been the case in state-run reserves. They have assets and that drives incentives to protect their property.

There are also elephants on private land in South Africa. But one of the ramifications of this conservation success story is that fewer private game ranchers want elephants because there are so many of the pachyderms in South Africa these days. So, South Africa’s elephant population could potentially be approaching a peak.

Ecotourism also plays a big role in the economics equation, both “non-consumptive” and “consumptive” – the former focuses on photographic wildlife excursions or simply watching animals, while the latter includes activities such as hunting.

With a couple of notable exceptions such as Kenya, southern Africa has by far the most developed “non-consumptive” ecotourism sector on the continent.

Botswana has Africa’s biggest population of elephants, with around 130,000. This state of affairs is partly explained by the fact that Botswana is sparsely populated by humans, who number around 2.5 million, and the pachyderms are mostly in remote areas with few people.

But Botswana also has a thriving non-consumptive ecotourism – or “safari” – sector that creates economic incentives to protect and maintain wildlife, including elephants. Tourism accounts, it seems, for about 13% of Botswana’s GDP.

Namibia, Zambia, South Africa and, to a lesser extent, Zimbabwe also have robust non-consumptive ecotourist offerings that bring in foreign currency, create jobs and business opportunities, and help ensure that prime elephant habitat is not turned into farmland or a mine or some such thing.

On the other hand

The flip side of the ecotourist sector is the elephant in the room – trophy hunting.

This makes animal welfare and rights activists, especially up north – you know, the countries that don’t have much in the way of dangerous megafauna – see red.

Opposition to hunting is perfectly legitimate; a lot of people simply do not like it for whatever reason.

But the problem is that it is often woefully misinformed and, in the case of Africa especially, fails to take into account the views of people who actually have to live in proximity to big animals that could kill their kith and kin or devour their crops.

One cold hard fact of this matter is that outside of Cameroon in the west and Tanzania in the east, southern Africa is the one region on the continent that also has several elephant range states, where the animals can be legally hunted for sport: South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Mozambique.

And this is the region that has gone against the grain of elephant decline in Africa. To use a term from the dismal science, this is called an “economic indicator” and, in this case, it is one that can also be seen as an “ecological indicator”.

There is a lot of wrangling about how much money from hunting trickles down to the rural poor, but the same can be said about photographic tourism. And many areas where hunting takes place are unsuitable for photographic tourism because of the terrain, remoteness and lack of amenities.

As the authors of the study note, their research is aimed at informing debate on these issues.

On that score, a recent Oxford-led study found that campaigns such as those in the UK to ban the import of hunting trophies – and Africa is the main target – were counterproductive “[…] as hunting does, or could potentially, benefit 20 species and subspecies, and people”.

“Legal hunting for trophies is not a major threat to any of the species or subspecies imported to the UK, but likely or possibly represents a local threat to some populations of eight species,” the study found.

When it comes to elephant conservation, the phrase coined by James Carville, a strategist in Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 US presidential campaign, comes to mind. “It’s the economy, stupid.” DM

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65750

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Elephant Management and Poaching in African Countries

Jumbo decline — elephant numbers plummet across most of Africa

'Within a single lifetime, we have pushed one of Earth’s most ancient species to the brink.' (Photo: Francis-Garrard)

By Don Pinnock | 14 Nov 2024

A groundbreaking scientific survey of savanna and forest elephants across 37 African countries has found an alarming decline in numbers over 50 years.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A continent-wide analysis by respected elephant scientists has found that within the single lifetime of a savanna elephant, their population has declined by 70% and in the lifetime of a forest elephant by 90%. The overall elephant decline is 77%. The scientists say these numbers could be underestimates.

The report, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, is one of the most comprehensive assessments ever taken of the two elephant species. It provides a much-needed quantitative assessment of their conservation status.

It used data from 475 sites across Africa going back to the 1960s, aggregating reports from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the African Elephant Specialist Group, the African Elephant Database, government survey reports and questionnaires across the 37 countries where elephants occur.

From the mid-20th century, human population growth accelerated exponentially and, in Africa, land conversion from wildlife into farming caused elephants to be compressed into existing or newly created protected areas. Outside these areas, conflict with them increased, leading to their persecution and decline.

The survey, say the scientists, spans 53 years, which is less than the lifetime of a long-lived elephant and a mere two elephant generations.

They found markedly different trends within and between regions. Some populations have disappeared entirely, with others showing rapid growth. Southern Africa saw a 42% average increase in savanna elephant populations, but only 10% of surveyed populations in eastern Africa have been increasing.

Elephant populations in the northern and eastern savannas crashed and — in many areas — have become extinct. However, it was a different story in southern Africa, where there were increases in more than half the sites.

In other areas there were pockets of increase within broad areas of decline, which the scientists say offer opportunities to identify opportunities for conservation efforts.

According to Boo Maisels, a conservation scientist at the Wildlife Conservation Society and a contributing author of the study, “While the overall picture is discouraging for both forest and savanna elephants, we see that some populations remain stable or are even growing.

“Examples [are] forest elephant of the Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park in the Republic of Congo and the Mbam et Djerem National Park in Cameroon, and for savanna elephants, the Katavi-Rukwa and Ruaha-Rungwa ecosystems in Tanzania and the Kaza [Kavango–Zambezi] landscape in southern Africa.

“Our results tell us that if well protected and managed, elephant populations can still increase despite increasing pressures surrounding them and their habitats. Elephants need our help now more than ever.”

“This study forces us to reflect on a sobering reality,” said Dr Mike Chase of Elephants Without Borders. “Within a single lifetime, we have pushed one of Earth’s most ancient species to the brink. It is both a warning and a call to action — one we can no longer afford to ignore.

“Yet, it also reminds us of our capacity for change — where we choose to protect, life endures. The fate of elephants — and perhaps our own — depends on whether we heed this urgent call to protect what remains.”

Senior author and elephant expert with Save the Elephants, George Wittemyer, said the study helped to pinpoint successful conservation actions in different contexts.

“We have to develop and implement a portfolio of effective solutions to address the diverse challenges elephants face across Africa.”

The study coincided with the World Wide Fund for Nature’s Living Planet Report, a comprehensive overview of the state of the natural world. Based on about 35,000 population trends across 5,495 species of amphibians, birds, fish, mammals and reptiles between 1970 and 2020, it found the size of wildlife populations plummeted by 73% on average, but 76% in Africa.

In the Kruger National Park, however, elephants are thriving, with the population at more than 30,000. By far the largest population covers a migration circuit between Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia and Zimbabwe with, at last count, numbers over 120,000. DM

'Within a single lifetime, we have pushed one of Earth’s most ancient species to the brink.' (Photo: Francis-Garrard)

By Don Pinnock | 14 Nov 2024

A groundbreaking scientific survey of savanna and forest elephants across 37 African countries has found an alarming decline in numbers over 50 years.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A continent-wide analysis by respected elephant scientists has found that within the single lifetime of a savanna elephant, their population has declined by 70% and in the lifetime of a forest elephant by 90%. The overall elephant decline is 77%. The scientists say these numbers could be underestimates.

The report, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, is one of the most comprehensive assessments ever taken of the two elephant species. It provides a much-needed quantitative assessment of their conservation status.

It used data from 475 sites across Africa going back to the 1960s, aggregating reports from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the African Elephant Specialist Group, the African Elephant Database, government survey reports and questionnaires across the 37 countries where elephants occur.

From the mid-20th century, human population growth accelerated exponentially and, in Africa, land conversion from wildlife into farming caused elephants to be compressed into existing or newly created protected areas. Outside these areas, conflict with them increased, leading to their persecution and decline.

The survey, say the scientists, spans 53 years, which is less than the lifetime of a long-lived elephant and a mere two elephant generations.