Casketts citrus farm debate

Posted on July 8, 2021 by Guest Contributor in the OPINION EDITORIAL post series.

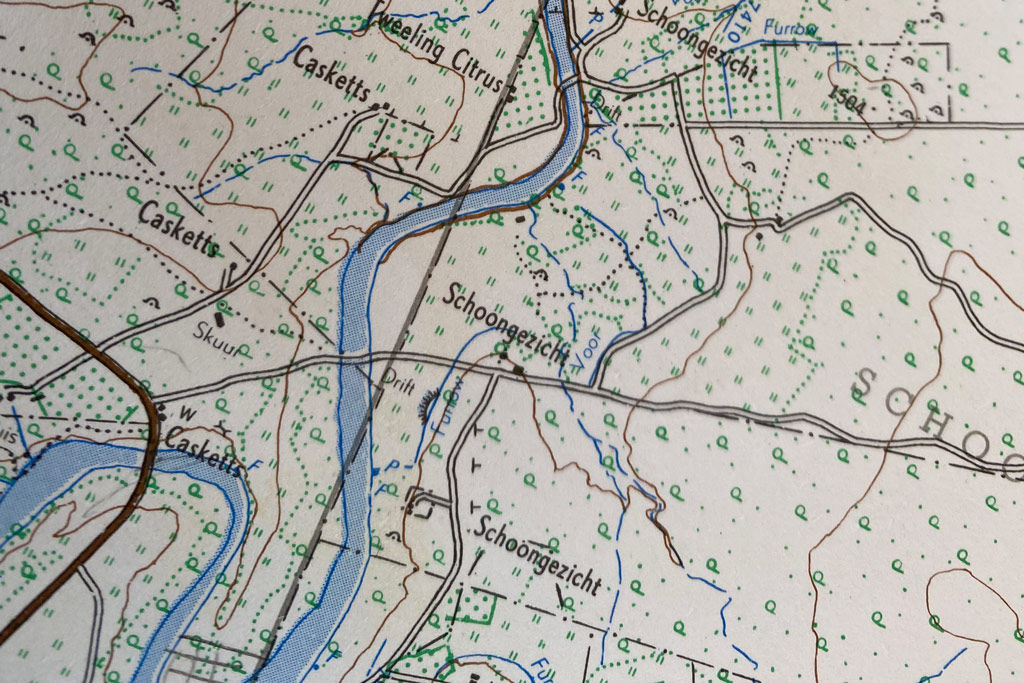

This opinion piece concerns the new Casketts citrus farm on the Greater Kruger border.

By Trevor Jordan

As a long-term resident of Hoedspruit, a wildlife property developer, and conservationist, I believe it is vital to understand that long-term conservation sustainability must consider the intersection of conservation organisations, agriculture, tourism, the causes of poaching and job creation. I believe it is necessary to address certain statements and misconceptions regarding the Casketts citrus farm.

Before I publicly air my views, I wish to state that the opinion expressed herein is personal and not representative of those held by any entities with which I am associated. I have no financial interest whatsoever in this matter. Instead, my involvement and interest are to seek the best possible outcome for all affected parties and the conservation ethos of the area.

Wide-open, undisturbed natural spaces, pristine landscapes without human interference, teaming with wildlife are the first prizes and dreams for me! This would, however, mean the exclusion of humans and their requirements. Is this possible? I do not think so, especially considering the world’s continued population growth.

It is, therefore, necessary to manage reality in the best way possible, to strike a balance between the conservation dream mentioned above and the burgeoning needs of human beings.

The Lowveld is a mixed-use area and has been for over a century. Hoedspruit town was founded in the mid 1900s as a railway siding on the Selati railway line and has been at the core of a growing economy that has still maintained ecological integrity and natural resources.

Mines opened in Phalaborwa, Gravelotte and Mica, and towns like Acornhoek and Bushbuckridge sprung up. The railway line and roads came a bit later. The Kruger National Park (KNP) was proclaimed a protected area to demarcate a zone that could not be mined, farmed, or occupied by human settlements.

Over time we have become ‘greener’ and endeavoured to practise more sustainable land use in the face of surging human population numbers. It is a difficult balance to achieve, but in Hoedspruit, we have accomplished many positive outcomes. We have removed many fences, creating more space for wildlife, partially restoring the historical, seasonal east-west migration patterns between the Mozambique coast and Drakensberg Mountains west of Hoedspruit.

Tourism played a significant role in this progress in the early 1980s. The opening of Eastgate Airport (previously the SANDF Hoedspruit air force base) with scheduled flights provided easy access and boosted tourism.

The success of tourism lodges has driven the demand to expand wildlife areas, with Big-5 safari operations being in high demand. These have created many jobs and opportunities for skills development.

The agricultural sector saw a swing away from livestock, with cattle farms converting to game areas to take advantage of the demand for tourism. Some areas close to perennial rivers were further cultivated under irrigation with high density and high-value crops. Like the tourism industry, the farms also created jobs and transferred skills. Both industries contributed to a vibrant economy and generated valuable foreign currency.

However, both these sectors face threats. For example, irrigation farms have limited water resources, while tourism could cause an overuse of land, threatening the exclusive ‘low volume, high value’ tourism model.

The neighbouring towns of Acornhoek and Bushbuckridge, previously tribal trust lands, are now some of the most densely populated areas in South Africa. They also experience one of the highest unemployment rates in the country. Despite the employment offered in tourist lodges and allied industries, these private reserves are perceived to be of little benefit to the communities. They are regarded as playgrounds for the privileged few. The populations are outgrowing the job availability in the tourism sector, exacerbated in these COVID times with job and income losses over 50%.

We need all forms of responsible economic development as there are many socioeconomic issues that, if not addressed, will become a significant threat to the stability of the region.

The Casketts citrus project is one that, as a conservation community, we should be encouraging and supporting, if not even partnering. It should not be seen as an enemy of conservation, as indicated by some. Rather it should be seen as a contributor to the local economy and one that will aid the socio-economic challenges that the region faces.

In 1991 I was involved in discussions regarding the western boundary fence of the Kruger, which led to the incorporation of the private reserves that now make up the Greater Kruger. The discussions were between the leadership of the KNP, the Transvaal Department of Nature Conservation, SA Department of Veterinary Services and Peace Parks. They were all very enthusiastic about the idea.

After discussion with the private reserves, independent landowners and other interested and affected parties, a conference was held at the Thornybush Game Lodge on 10 and 11 August 1991. Besides the KNP fence and private land incorporation discussion, the conference’s central theme was: “Die bewaarings toekoms van die Laeveld” – The Conservation future of the Lowveld.

After robust discussions, the delegates came to the following non-negotiable directives that were to be implemented in conjunction with the removal of the western fence:

1. There was a need for a collaborative process involving all interested parties;

2. That a task force be established;

3. Unifying conservation in the region to enhance its benefits and be of relevance to all its inhabitants. Consideration was to be given to some critical points:

- Our natural resources are there for all the region’s inhabitants and should be considered an asset to everyone;

- The disproportionate population increase in the region, which was well more than the average birth rate, presented the prospect of increased deprivation, unemployment and pressure on the land;

- Historically, the perception existed that conservation and the current model of land usage were irrelevant to the requirements of the various human communities. This was to be addressed through consultation, participation, and optimal economic development;

- The region’s resources and existing forms of economic utilisation, such as commercial lodges, hunting and agriculture, constituted a competitive advantage in the national and international market, capable of elevating these businesses through increased revenues and job creation;

- Economic development and tourism expansion need not be inconsistent with nature conservation, as long as the concept of sustainable utilisation is applied;

In an ideal world, we would prevent agricultural development from happening near this highly prized conservation area; however, if this massive job creator can conserve our rhino through feasible employment (thereby reducing one root cause of poaching), I feel this is a reasonable and necessary compromise to make.

We cannot afford the luxury of pure wildlife conservation areas – the dream I wrote of earlier in this letter. I believe that sustainable, responsible agricultural developments that create much-needed employment for neighbouring communities should be wholeheartedly embraced and not seen as an enemy to conservation.

———-

Trevor Jordan is a property developer and conservationist. His residential estate and game lodge developments are dotted throughout the Lowveld area of South Africa, and his many conservation activities in the region have added significantly to the cause.