From left to right: Between 2 and 4 November 2023, 18 barn swallows were found dead under a power line on a farm in Lobatse, Botswana, following several days of cold and wet weather. (Photo: Mark Bing) / Barn Swallow. (Photo: Mark Anderson) / Two bee-eaters found dead in Delta Park, Johannesburg on 1 November. (Photo: Sandra Maytham-Bailey via Facebook)

By Julia Evans | 12 Nov 2023

After a drastic change in weather last week, birds were found dead across the country, highlighting the ecological cascade climate change will bring.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

After travelling south for their annual migration, European bee-eaters and swallows were met by extreme weather conditions – cold temperatures, strong winds and heavy rain – when they arrived in South Africa last week.

Meteorologist Annette Botha, from Vox Weather, told Daily Maverick that while a swing in temperature at this time of year (spring, the transitional season) is normal, this extreme swing – going from heatwaves earlier in the week to record-breaking cold weather (the lowest maximum temperature, 8.1℃ in Zuurbekom, broke the record set in 1965) – is very rare for this time of year, although not unprecedented.

“This steep drop, especially for that time of the year, is something that I’ve never seen before as a meteorologist,” said Botha.

“The result was devastating, with reports pouring in of numerous European bee-eaters and swallows found lifeless throughout the country,” reported BirdLife, first flagging reports on social media of citizens posting between two and 60 European bee-eaters and swallows found lifeless throughout the country – in the Highveld area in Gauteng, North West, Mpumalanga, Limpopo and Eswatini and as far west as Sodwana Bay and as far south as the South Coast of Durban.

In Johannesburg, 33 bee-eaters were found dead under a collection of exotic trees close to Braamfontein Spruit in Parkhurst, where the birds roost at night, on 1 November, just one day after the sweltering heat hit. Residents said these birds have returned to these trees every October for the past decade at least.

Thirty-three European bee-eaters were found dead under a collection of exotic trees where the birds roost at night, on the Braamfontein Spruit in Parkhurst, Johannesburg, on 1 November 2023, following cold and wet weather. (Photo: Stanley Bawden)

Resident Linda Hart sent the birds to Friends of Free Wildlife for forensic investigation by Onderstepoort, where they were found to be free of poisoning and disease, and concluded that the birds died of natural causes due to the extreme weather and their weakened state owing to their recent migration.

Andrew McKechnie, a professor of zoology at the University of Pretoria, whose research has focused on how birds and other animals are being affected by climate change, told Daily Maverick: “What probably happened was, you had migrants that had recently arrived from long flights from Europe… in relatively poor body condition because of those flights… when migratory birds fly long distances they burn up all of their fat stores, they sometimes even start metabolising protein.”

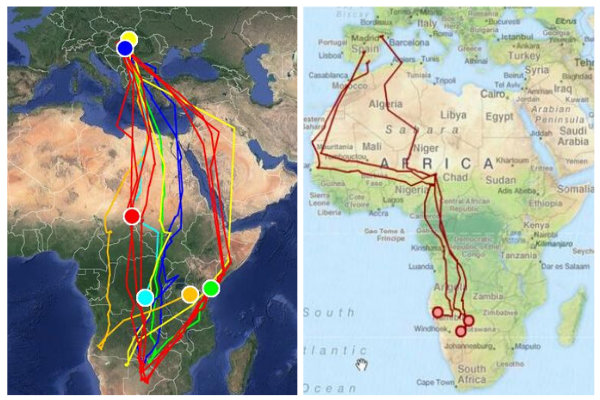

BirdLife SA’s Flyway and Migrants Project manager, Jessica Wilmot, said that just to get here migratory birds face many threats as the birds’ “key stopover” points along the way are likely to be deteriorated (due to urbanisation, agricultural expansion, biodiversity loss and climate change), so they wouldn’t have the resources to arrive in a strong condition.

Along with that, the birds’ immune system might be further compromised from ingesting toxins during migration. Wilmot explained that because these birds are aerial feeders they often ingest the agricultural chemicals that farmers spray for pests, through eating insects that have come into contact with those toxins.

McKechnie and Wilmot said that because the types of birds found dead are aerial feeders, they’re particularly vulnerable to a seasonal cold snap, because the sudden drop in temperature at the end of October would mean fewer flying insects to feed on and refuel when they arrived in South Africa.

How tragic to survive such an extensive journey only to succumb to an abnormal weather event.

And the rain and wind didn’t help their odds either. McKechnie said birds lose a lot more heat through wet feathers than dry, so when it rains the insulation feathers provide drops precipitously – greater the air movement means faster heat loss.

“It’s a very simple issue of whether they can gain enough energy from feeding to balance the energy requirements. Suddenly the weather turns cold [and] energy requirements go up, because they’ve got to produce heat to keep warm. But if your food availability has dropped off a cliff, it’s going to be that much more difficult to balance energy supply and demand.”

So, when these birds arrived in South Africa they were weak from travelling, probably underresourced and with weakened immune systems. Their poor body condition meant they didn’t have the energy to fight the cold, coupled with the fact that they had to go a few days without food.

“The European bee eaters are generally very adaptable. But I just think it [the combination] was almost just too much for them to handle,” said Wilmot. McKechnie agreed, saying birds can survive cold conditions if they have the energy supply and behaviours to allow them to do that.

“How tragic to survive such an extensive journey only to succumb to an abnormal weather event.”

Barn swallows. (Photo: Mark Anderson)

Climate change

Extreme weather conditions, such as last week’s extreme rainfall, wind and cold, while rare for spring, are naturally occurring, and would happen even if humans didn’t exist.

But what’s important to understand is that there is consensus among the scientific community that extreme weather events (flooding, heatwaves, wildfires, droughts, cyclones) are increasing in intensity and frequency due to anthropogenic climate change, posing serious threats to conservation.

McKechnie, who is also the South African Research Chair in Conservation Physiology at the South African National Biodiversity Institute, said: “For rare species, extreme weather events like this can have a catastrophic effect on population.” A single weather event could wipe out an entire vulnerable population.

And it’s not just rain and cold weather that affect birds.

McKechnie, also the co-principal investigator of the international multidisciplinary Hot Birds Research Project – which for the past decade has been aiming to learn how desert birds will be able to withstand rising temperatures caused by climate change and an expected 3°C temperature rise in some parts of the world – said that the effects of heatwaves are already being seen.

In 2018, a third of Australia’s population of spectacled flying foxes (a type of fruit bat) died over two extremely hot and humid days.

The first such event in South Africa was around Pongola in northern KwaZulu-Natal, where on a humid day in November 2020, temperatures reached 45°C, and 12 species of likely thousands of birds died.

McKechnie explained that, like any animal, including us, birds need to keep their body temperatures below lethal limits to avoid heatstroke. However, birds are not as good at tolerating heat as humans, one of the most heat-tolerant species of mammal on the planet.

- I don’t think people actually realise how important it is to just log sightings of birds. We’re very dependent on citizen science to do anything.

When it’s hot (35°C and higher) birds will seek shade, exerting energy to keep cool (evaporating water, panting), instead of foraging for food and water, which means they are not able to replace the water and mass they are losing.

The European bee-eater. (Photo: Albert Froneman)

Ecological cascade

These extreme weather events affecting bird populations will have knock-on effects as well, since birds provide vital ecosystem services.

For example, more than a decade ago, after a fungal disease in North America compromised bat populations, a study done to estimate the value of ecosystem services bats provide suggested that loss of bats in North America could lead to an estimated $3.7-billion in agricultural losses per year.

McKechnie said that study illustrated how important the ecosystem service of pest control is, which birds also provide.

Trumpeter hornbills, for example, perform the vital ecosystem service of seed dispersal on the East Coast, where forest ecosystems rely hugely on large birds to do this.

“If you lose a species like trumpeter hornbills, you’re going to suddenly have lost your seed-dispersal agent for particular species of trees.”

Citizen science

“The disconcerting truth is that while anthropogenic-induced warming is driving the increase of extreme climate events globally, the ecological cascading effects of these events as a severe threat to the conservation of migratory birds, have largely been understudied,” BirdLife SA said following last week’s devastating bird deaths. “Consequently, documenting the extent of these events is vital.”

Said Wilmot: “I don’t think people actually realise how important it is to just log sightings of birds. We’re very dependent on citizen science to do anything.”

Wilmot suggests that people log any bird sightings, not only deaths, on apps such as BirdLasser and eBird. DM